To read this report as a PDF, click here.

As wealth and income gaps between average New Jerseyans and the state’s wealthiest households continue to grow, policymakers must take steps to address this extreme inequality. One of the most effective ways to do so is to restore fair and adequate taxation of inherited wealth. This targeted tax policy can help close the wealth gap in the long run by facilitating crucial investments that can boost all New Jersey families – not just those that pass millions of dollars down from one generation to the next.

Decades of uneven income and wealth growth have put the wealthiest residents miles ahead of everyone else. This has made it harder for most families striving to get ahead and put a strain on future economic growth. In fact, these widening disparities have been responsible for having depressed U.S. economic growth by more than 20 percentage points from 1990 to 2010.[1]

And New Jersey is among the states where this trend is most pronounced.

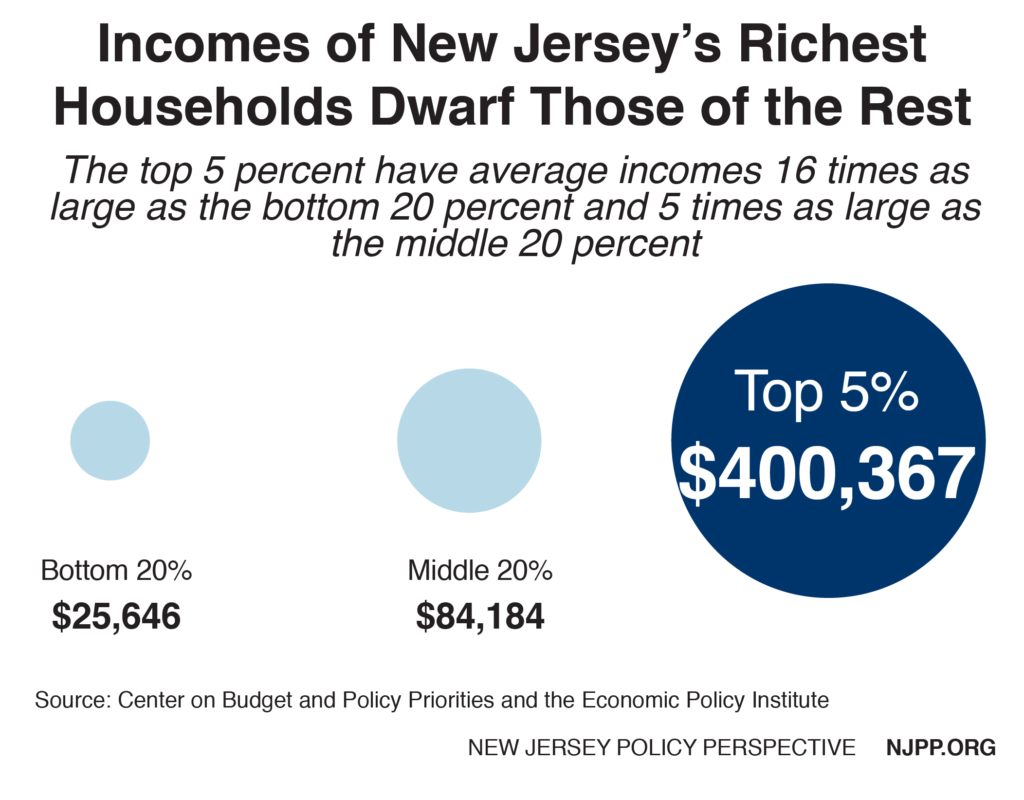

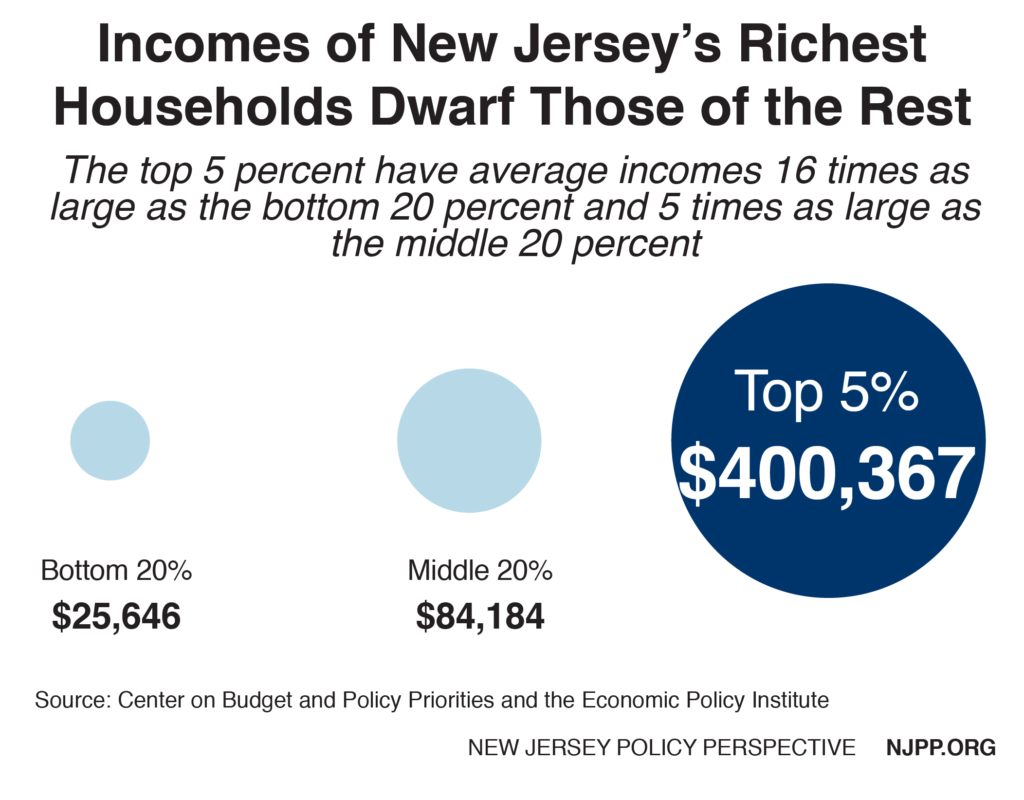

New Jersey has the seventh widest income gap in the country, with the wealthiest 5 percent of households earning an average of 16 times more than the poorest 20 percent, and an average of five times more than the middle 20 percent.[2] And these figures significantly understate the disparity, because they don’t include income from capital gains – which go disproportionately to the richest households.

The income of the richest 1 percent of households in the Garden State grew 190 percent between 1979 and 2013, while everybody else’s income grew just 20 percent. A lopsided gain on that scale hasn’t been seen in New Jersey since the Gilded Age in the 1920s.

One of the most effective ways to promote widespread prosperity is to tax inherited wealth. For decades New Jersey has done just that by levying both an estate tax and an inheritance tax and using the revenue for assets like public colleges, safe communities and health care that benefit everyone.

One of the most effective ways to promote widespread prosperity is to tax inherited wealth. For decades New Jersey has done just that by levying both an estate tax and an inheritance tax and using the revenue for assets like public colleges, safe communities and health care that benefit everyone.

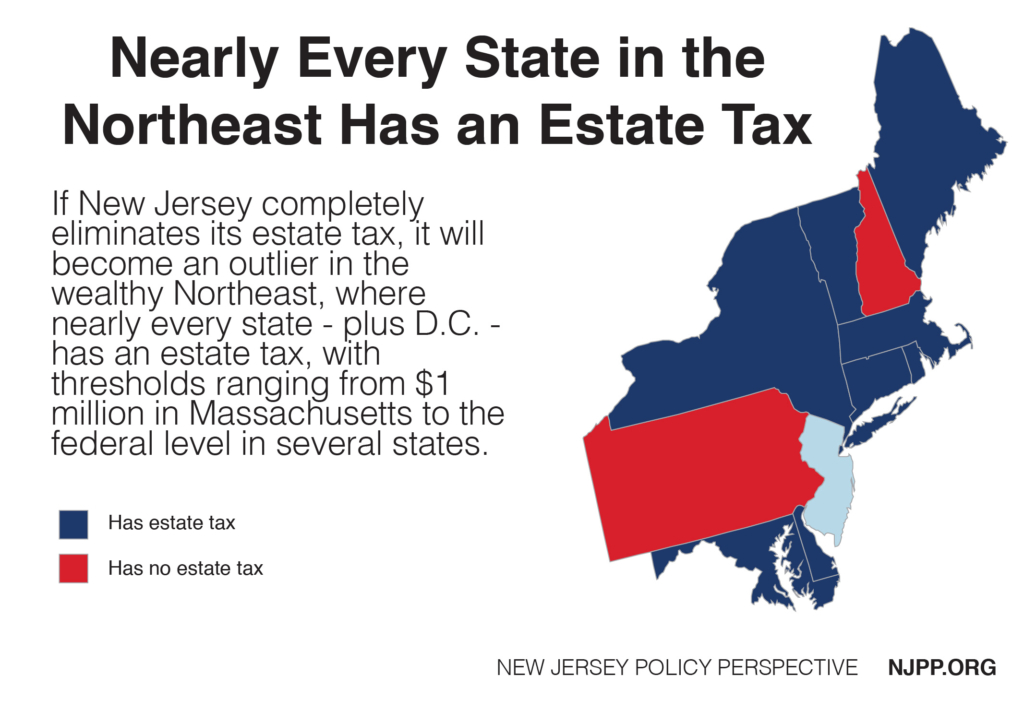

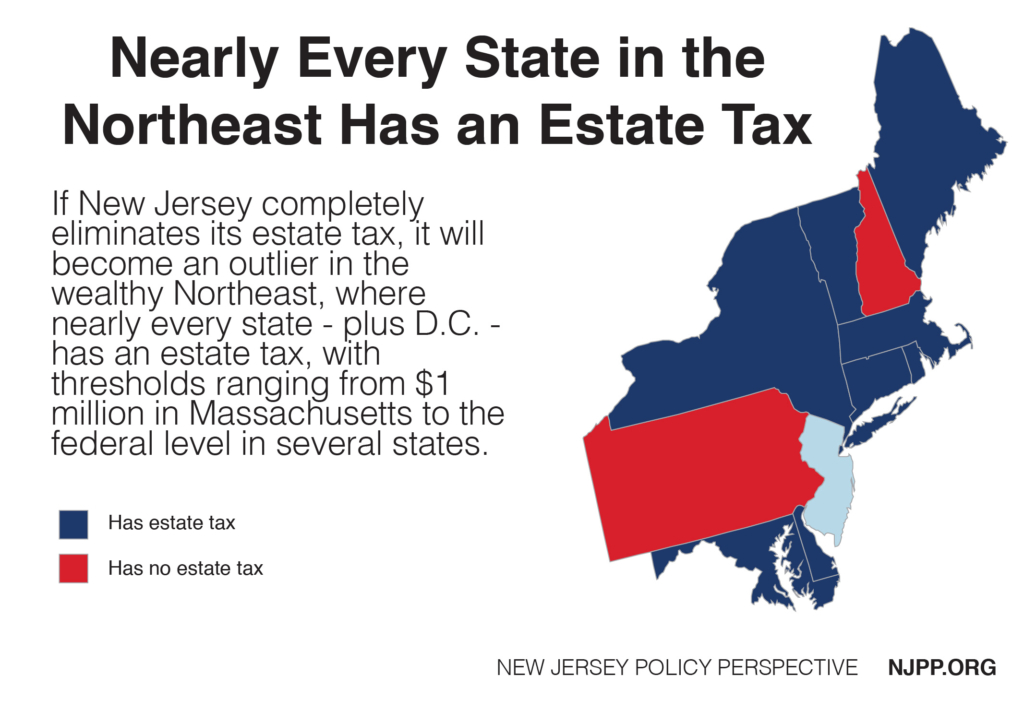

Currently, 18 states plus D.C. levy either an estate tax, an inheritance tax or both. States that tax inherited wealth include – not surprisingly – most of the country’s wealthiest states. In fact, 4 of the 5 states with the highest median household income, and 4 of the 5 with the highest share of millionaire households, tax inherited wealth.[3] And 15 of the 18 states have a higher median household income than the country as a whole.

In New Jersey, very few heirs pay these taxes on inherited wealth: about 5 percent of heirs pay the estate tax, and about 5 percent pay the inheritance tax – and many pay both, so overall fewer than 10 percent of heirs pay these taxes.

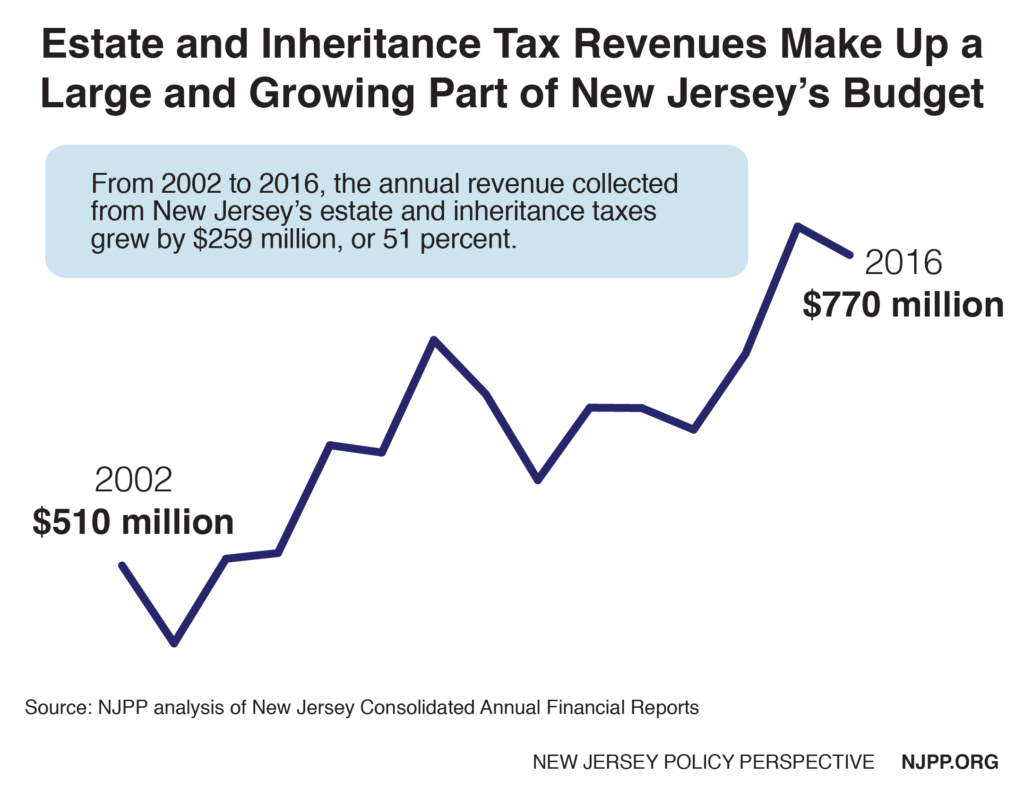

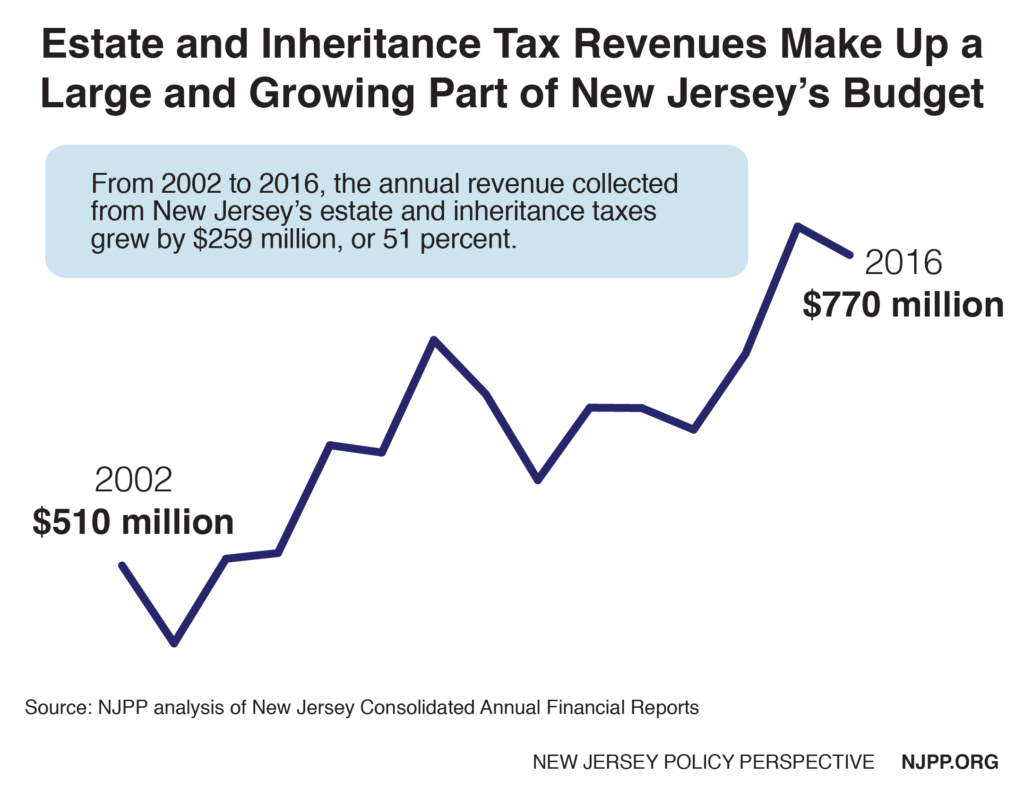

The estate tax is paid by estates based on the net value of its assets on the day of the death; the inheritance tax is paid by individuals who receive gifts from estates. Together, these taxes bring in more than half-billion dollars in annual revenue and have been a reliable, even growing, source of funding for New Jersey. Last year they brought in nearly $770 million – a 51 percent increase since 2002.[4]

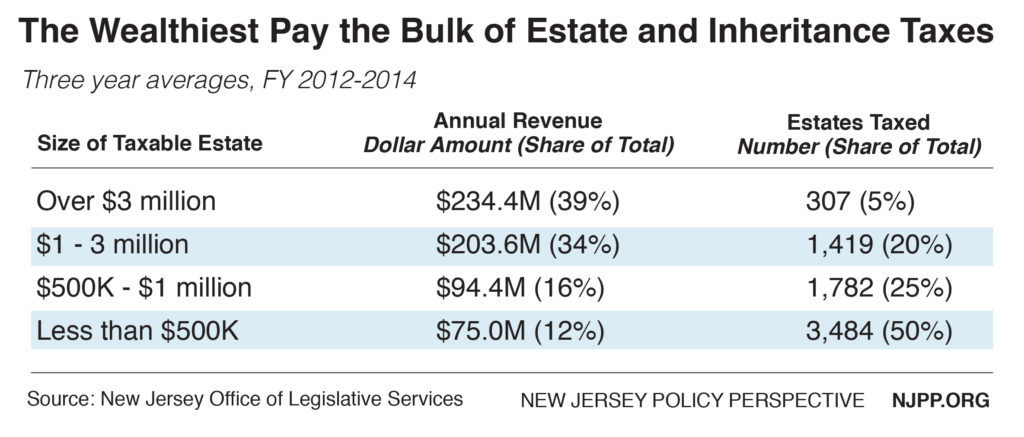

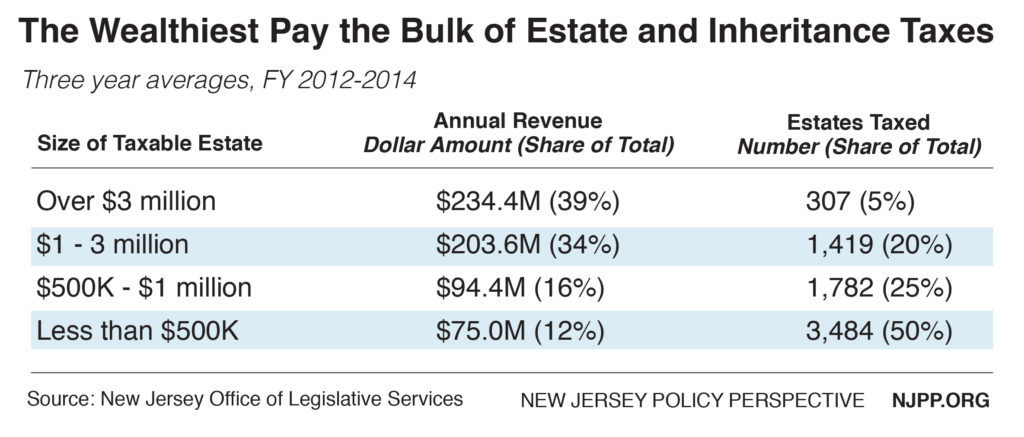

Some 300 estates – the very largest, with taxable assets over $3 million – pay 39 percent of estate and inheritance taxes in a given year.

However, New Jersey’s estate tax is on course to be fully repealed on January 1, 2018, giving a spectacular tax break to a few thousand of New Jersey’s wealthiest families and significantly reducing the state’s capacity to make investments benefitting all New Jerseyans. Policymakers should reverse course by restoring fair and adequate taxation of inherited wealth by either bringing back the estate tax, reforming the inheritance tax or some combination of both.

Restoring New Jersey’s Estate Tax

For decades, New Jersey’s estate tax has been paid by heirs of estates worth over $675,000, with tiered tax rates topping out at 16 percent. Just 4 to 5 percent of estates – those of New Jersey’s wealthiest households – are large enough to owe any estate tax. Nothing passed on to a surviving spouse, civil union partner or domestic partner is subject to the estate tax. And the amount of estate tax owed is reduced by any New Jersey inheritance tax paid, ensuring that inherited wealth is not taxed twice.

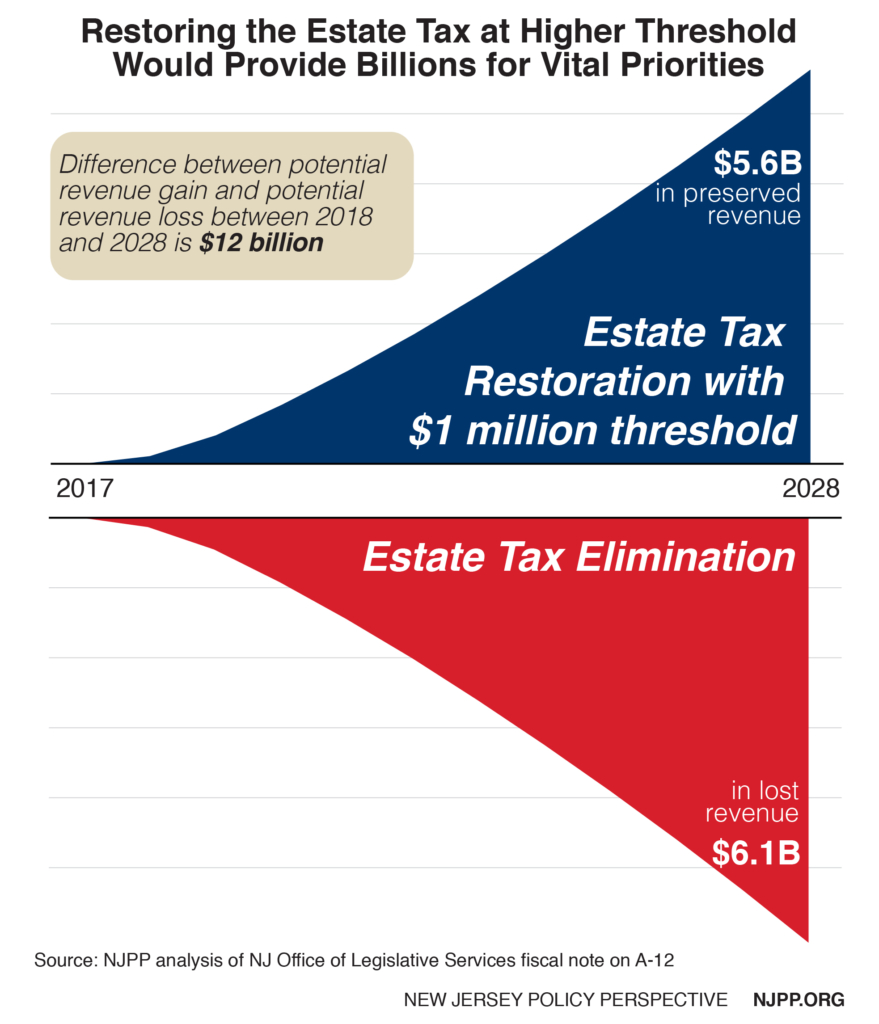

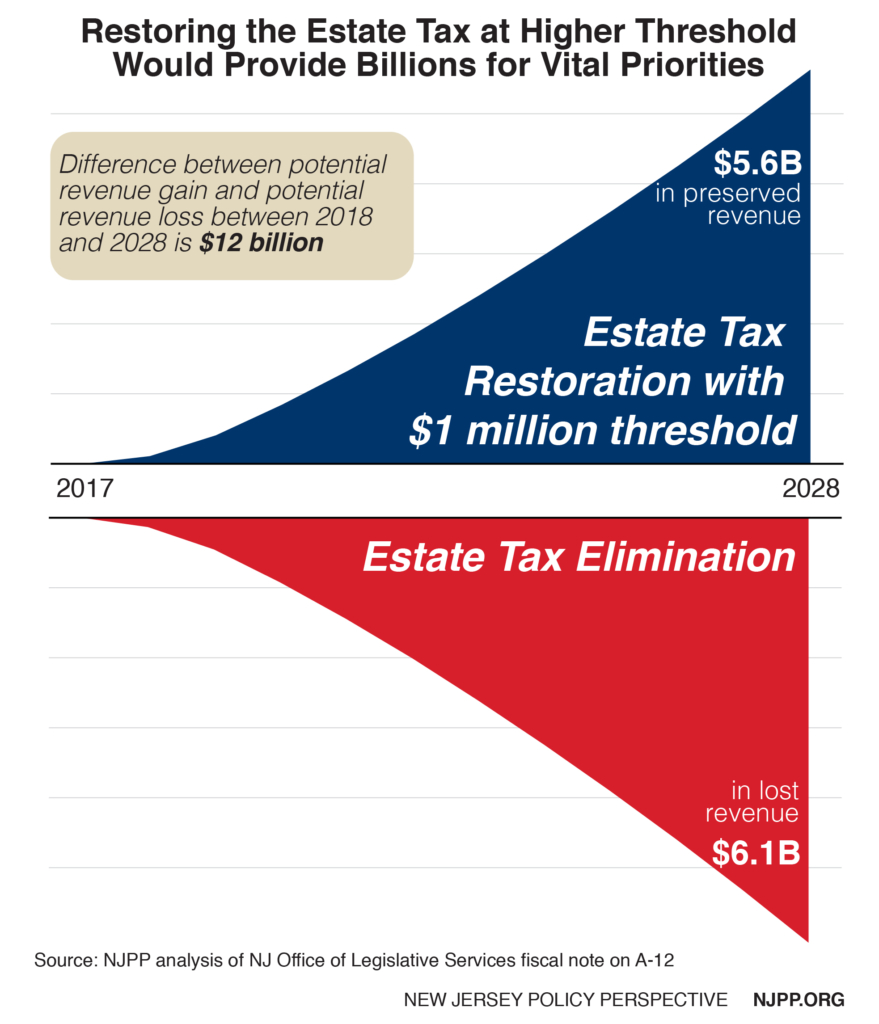

Once the estate tax is fully repealed, the state will lose about $500 million a year, greatly reducing the state’s ability to make crucial investments while further enriching the heirs of New Jersey’s wealthiest families.[5]

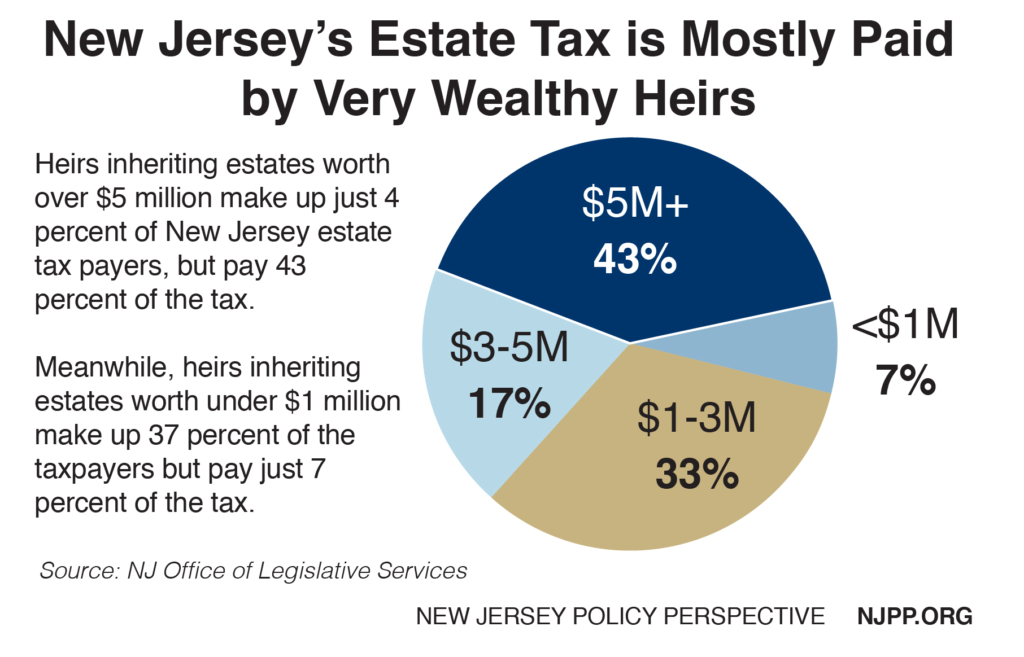

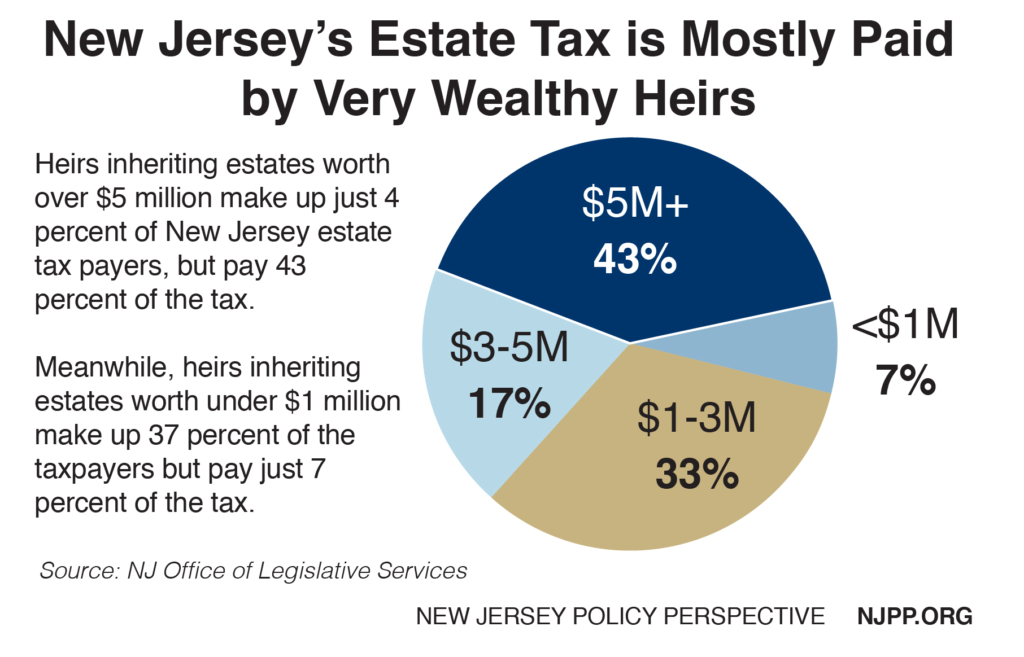

It’s from those inheriting extreme amounts of wealth that the estate tax collects the bulk of its dollars. In fact, the largest 4 percent of estates make up 43 percent of the tax paid, while the smallest 37 percent of estates make up just 7 percent. Eliminating this tax gives those inheriting estates worth more than $5 million a tax break averaging a whopping $1.1 million – a reduction 51 times larger than the break for those inheriting estates with taxable assets between $675,000 and $1 million.

By restoring the estate tax with a higher threshold, New Jersey could regain the lion’s share of estate tax revenue it has collected while ensuring that the wealthiest heirs pay their fair share. For example, reinstating the tax on estates worth more than $1 million would recoup 93 percent of the tax revenue, preserving an estimated $5.6 billion over the next decade – dollars that are sorely needed to meet the needs of all New Jersey families and invest in the building blocks of a strong economy.

That would put New Jersey back on the map with other wealthy states and neighboring states that tax inherited wealth.

Strengthening New Jersey’s Inheritance Tax

New Jersey is one of six states that collect an inheritance tax. Established in 1892, this tax is levied on inheritances over $25,000 for some relatives and on inheritances worth over $500 for estates inherited by non-relatives. The tax rate now ranges between 11 and 16 percent depending on the relation to the decedent and size of the estate. Most close relatives are exempt, as are charitable donations. Over 5,000 estates are subject to the tax per year bringing in between $300 million and $400 million per year.

While lawmakers eliminated the estate tax last year, they left the inheritance tax in place. If New Jersey is to depend on the inheritance tax as its only source of taxation of inherited wealth, then policymakers must reform it to make it fairer and more adequate.

Currently, bequests exceeding $25,000 are taxed at 11 to 16 percent, depending on the gift’s value. This applies to siblings (including half brothers and sisters), the spouse, widow or widower of the decedent’s child, and the surviving civil union partner of the decedent’s child. These beneficiaries make up 30 percent of inheritance tax filers and bring in 20 percent of the revenue.

The bulk of the inheritance tax is paid by a class of non-exempt beneficiaries that includes aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, cousins and other heirs. These include out-of-state beneficiaries as the tax is applied to the deceased person who lived in, or had property in, New Jersey. They pay 15 percent on the first $500 to $700,000 they receive and 16 percent on anything above that amount. These filers pay about 80 percent of all the inheritance tax revenue.[6]

The most effective way to reform the inheritance tax would be to expand the types of heirs required to pay the tax. Bringing the exemptions to the inheritance tax in line with those who are exempt from the estate tax – namely ensuring that a spouse or domestic partner of the deceased remains exempt – would increase the amount of revenue collected by this tax. This means family members like descendants, parents and grandparents would be required to pay inheritance tax.

In addition to expanding the universe of those who are subject to the tax, lawmakers ought to reform the inheritance tax to ensure that only New Jersey’s wealthiest heirs pay the tax. Creating a exemption up to $1 million would keep this tax fair and help guard against concentrated wealth.

Lawmakers should also explore tweaking – and simplifying – the inheritance tax rates. Currently the top rate of 16 percent kicks in at $1.7 million for some heirs, and $700,000 for others. If no tax was levied on estates under $1 million, adopting a simplified bracket system with progressively higher rates at each million-dollar mark and ranging from 11 to 20 percent would be sensible.

Taxing Inherited Wealth Has Little Impact on Retiree Interstate Moves

Despite stories to the contrary, there is no credible evidence to support the claim that New Jersey’s elderly residents are fleeing taxes on inherited wealth by moving to lower-tax or no-tax states. In fact, the annual revenue collected from the estate and inheritance taxes has been consistently reliable – and growing. Any revenue loss from wealthy retirees choosing to leave the state to avoid these taxes hardly compares to the significant revenue raised by them.

In the most rigorous study on the effect of estate taxes on interstate moves to date, the patterns of state-to-state movement among American elderly have remained relatively consistent over time, even as state tax policies toward the elderly changed significantly across states.[7] In other words, if older people who leave New Jersey are heading to popular retiree destinations regardless of tax policy, there is no reason to offer them tax breaks in the hopes that they will stay.

Endnotes

[1] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth, December 2014.

[2] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Economic Policy Institute, How State Tax Policies Can Stop Increasing Inequality and Start Reducing It, December 2016.

[3] Five highest median household income states taken from U.S. Census American Community Survey, 2015. Five highest shares of millionaire households taken from Phoenix Marketing International, Millionaires By State Ranking, 2010-2016.

[4] New Jersey Department of the Treasury, Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, FY 2001 – FY 2015.

[5] New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Legislative Fiscal Estimate of A-12, October 2016.

[6] For more details on who is exempt from the inheritance tax, visit www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/pdf/other_forms/inheritance/transferinheritanceclasses.pdf. For more details on the tax rates, visit http://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/inheritance-estate/tax-rates.shtml

[7] National Tax Journal, No Country for Old Men (Or Women): Do State Tax Policies Drive Away the Elderly?, June 2012.