Negotiated behind closed doors and voted on without public input, the latest state budget wasted a historic opportunity to fix New Jersey’s finances and boost investments in historically underfunded areas. Instead, lawmakers used record-setting revenue collections to fund costly tax cuts and credits for wealthy households and profitable corporations, threatening the state’s long-term fiscal health.

On the positive side, the $54.3 billion budget for Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 includes another full pension payment and a record level of school funding.[i] The budget also continues investments in the many building blocks of a strong and healthy state: expanded pre-K, increased college tuition assistance, increased access to affordable health care, and much more.

However, three major red flags in the budget undermine the sustainability of these essential public services and programs.

Red Flags: A Shaky Fiscal Footing

New Jersey, like every state, is required to pass a balanced budget, meaning it must raise enough revenue to account for all of its expenses. The major changes in this year’s budget, to both the tax code and expenditures, have the state spending more than it takes in, raising three red flags about the state’s ability to pass a balanced budget in subsequent years. First, the growing investments in the budget rely on a temporary boost in tax collections that is already declining. Second, new corporate tax cuts and tax credits for wealthy homeowners will further weaken future revenue collections. Third, the budget relies on federal pandemic aid that will soon expire, creating looming funding shortfalls that must be addressed as early as next year.

Despite the budget’s continuation of important investments, it will largely be remembered for its short-term giveaways to profitable corporations, wealthy individuals, and politically-connected insiders who loaded up line items and side deals, while kicking long-term structural budget problems down the road.

Red Flag 1: Declining Revenues, Shrinking Surplus

The FY 2024 budget includes new and growing investments that will require consistent funding in future years. Yet, the revenue streams supporting these investments are already starting to wane. Recent revenue snapshots show that last year’s unprecedented boost in tax collections was temporary, with the state’s major revenue sources on the decline.[ii] Bringing in less revenue threatens the sustainability of the investments made in the latest state budget and could hamper future improvements to public services and programs that New Jersey families, communities, and businesses rely on.

Increased spending and declining revenues leave the state at a structural deficit, with expenditures now surpassing revenue collections by roughly $1.5 billion. This deficit is already eroding the state’s historic surplus, as the Governor’s original $10 billion projected surplus for FY 2024 has already come down to $8.1 billion.[iii] That means the state has less of a safety net if revenue collections continue to decline in the near future.

The shift in revenues and expenditures between the budget initially proposed by Governor Murphy and the one ultimately signed into law should serve as a clear warning signal for the state.

Table: Appropriations Surpass Revenue Collections in FY 2024 Budget

|

Original Proposed Budget |

Final Approved Budget |

| Revenues |

$53,828,554 |

$52,801,265 |

| Appropriations |

$53,084,949 |

$54,357,547 |

| Net difference |

+$743,605 |

-$1,556,282 |

Source: FY 2024 Appropriations Bill Scoresheet: https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/Scoresheet,%20As%20Introduced.pdf

The surplus funds won’t last long if New Jersey continues to spend more than it generates in revenue, a trend likely to continue given the elimination of the corporate business tax surcharge and other tax giveaways buried in the budget deal. The state’s Rainy Day Fund also remains woefully drained, leaving New Jersey unprepared to weather bumpier economic conditions in the years to come.[iv]

During the Great Recession, the state saw the devastating consequences of costly tax cuts and an empty reserve.[v] New Jersey cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the past, especially now, as far too many families are struggling to keep up with rising costs and afford basic expenses. Lawmakers must prioritize tax policies that generate enough revenue to both cover the state’s expenditures and build up reserves so vital state services are there for families and communities when they need them the most.

Red Flag 2: Costly Corporate Tax Cuts and Credits

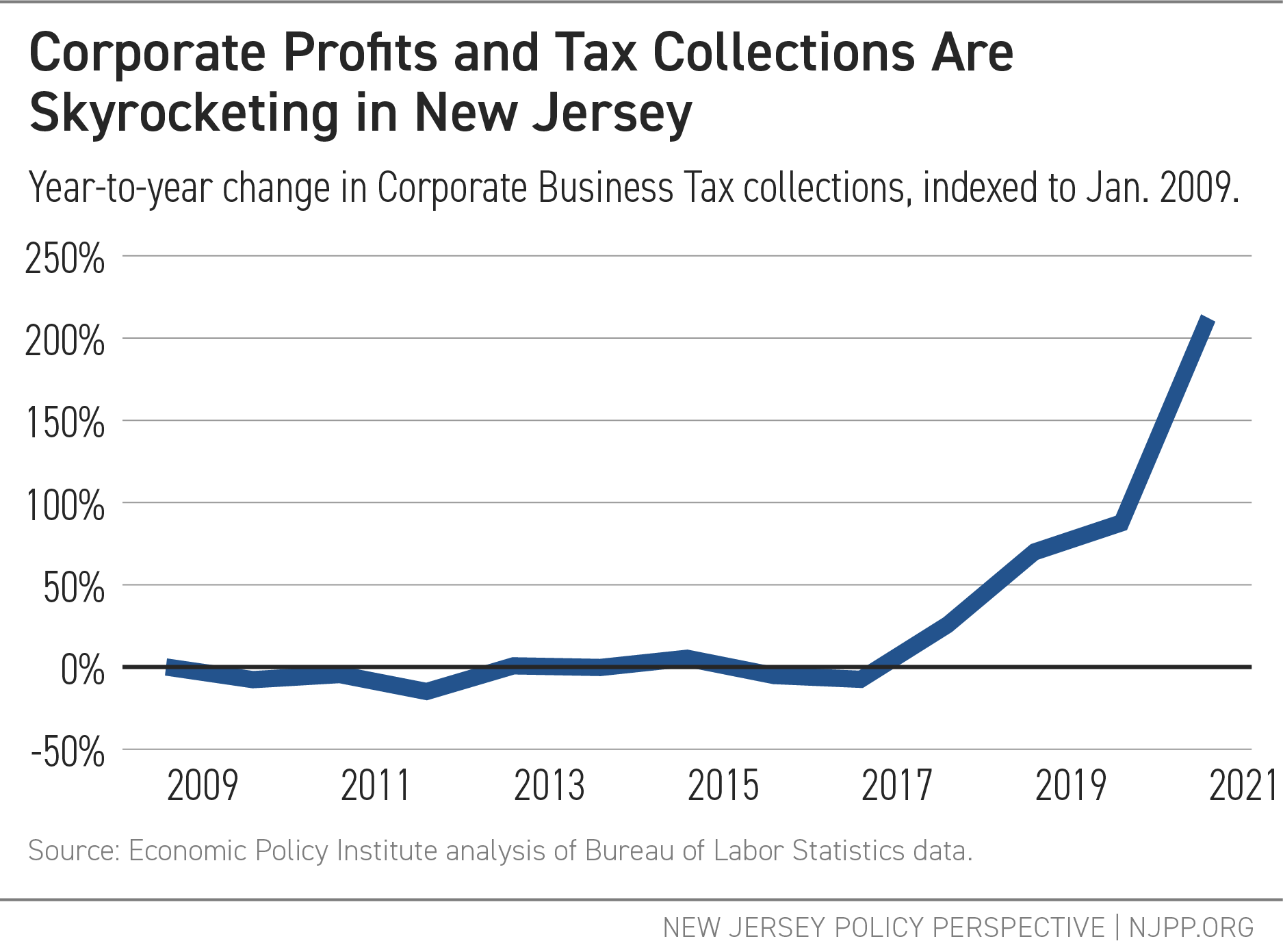

Even with increased investments that will require consistent funding in future years, the new state budget contains a $1 billion tax cut for the world’s biggest and most profitable corporations.[vi] Add in other corporate tax changes that reward offshoring of profits to foreign countries, hundreds of millions in tax credits for specific industries, and a costly property tax credit program that will disproportionately benefit wealthy households, and New Jersey could experience significant revenue losses in the face of rising costs and potential economic turmoil.

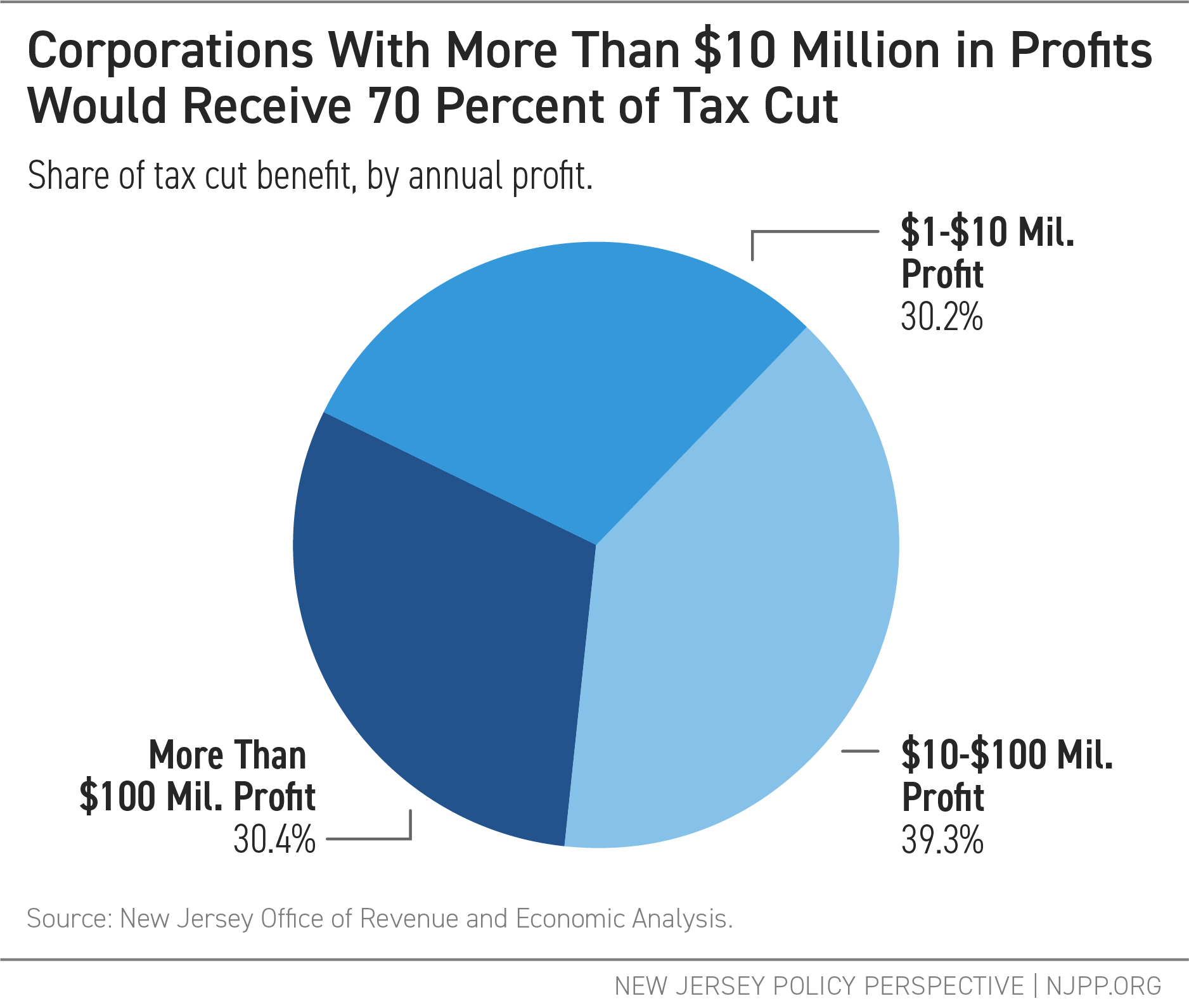

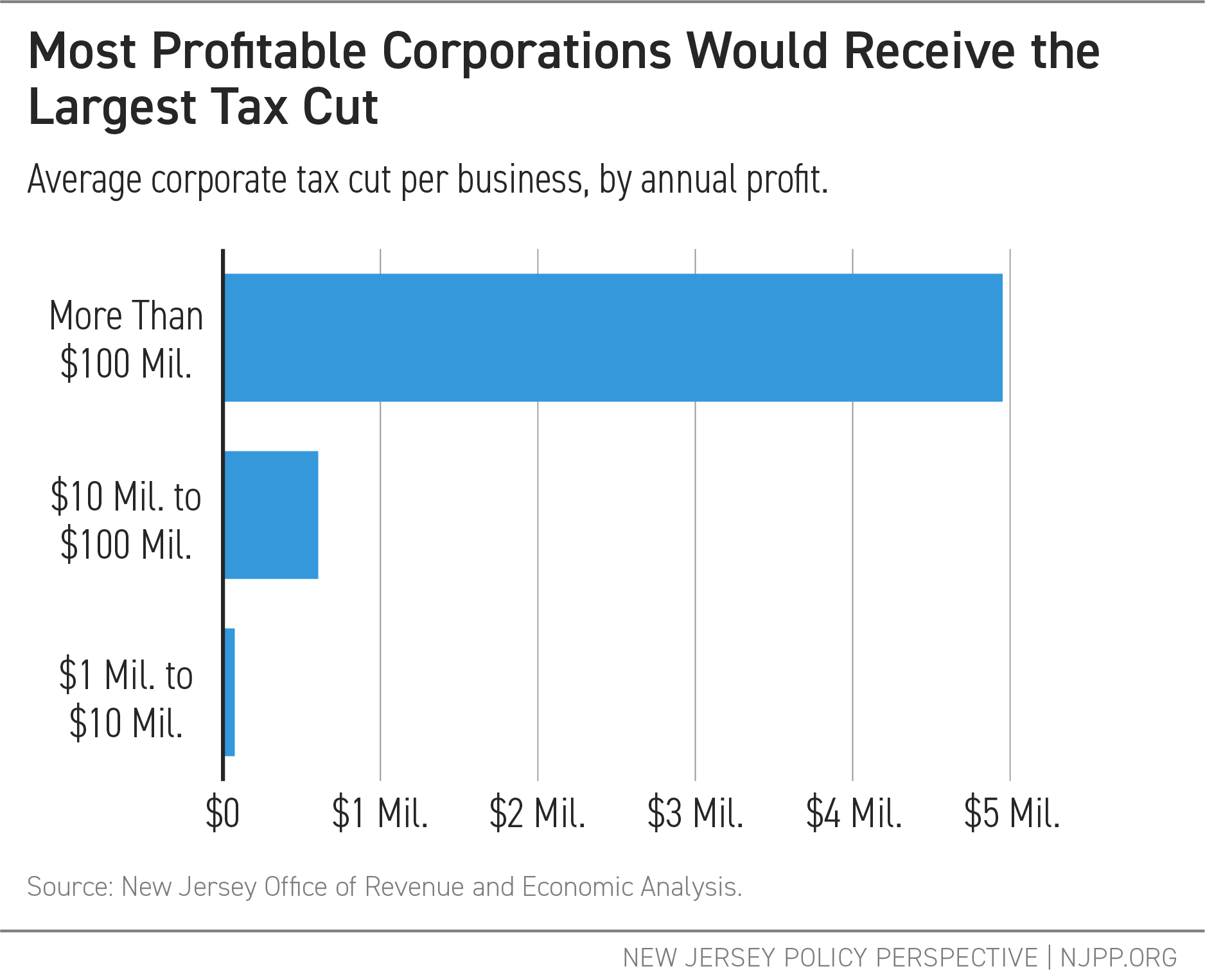

For context, the Corporation Business Tax currently includes an additional 2.5 percent surcharge on businesses with more than $1 million in profit. The surcharge, which will expire unless it is renewed before the end of the calendar year, only applies to the top 2 percent of businesses earning the most in profit.[vii] This includes all corporations that generate profit in New Jersey — including multinational corporations, e-commerce sites, and chain retailers like Amazon, Walmart, and Starbucks — not merely companies headquartered in the state. Eliminating the surcharge would enrich a select few corporations and their shareholders at the expense of workers and families who benefit from the various investments in infrastructure, transit, schools, and safety net programs that the surcharge helps fund.

The budget also includes new legislation that will open up more loopholes in the corporate tax code, which may accelerate the erosion of the corporate tax base even further.[viii] These changes would allow multinational corporations to evade taxation by shifting their income to subsidiaries based in foreign tax havens. Though billed as “revenue-neutral,” these changes would reward corporations who shift profits abroad, reducing their tax liability in future years and continuing a trend of eroding corporate tax bases at the state level.[ix]

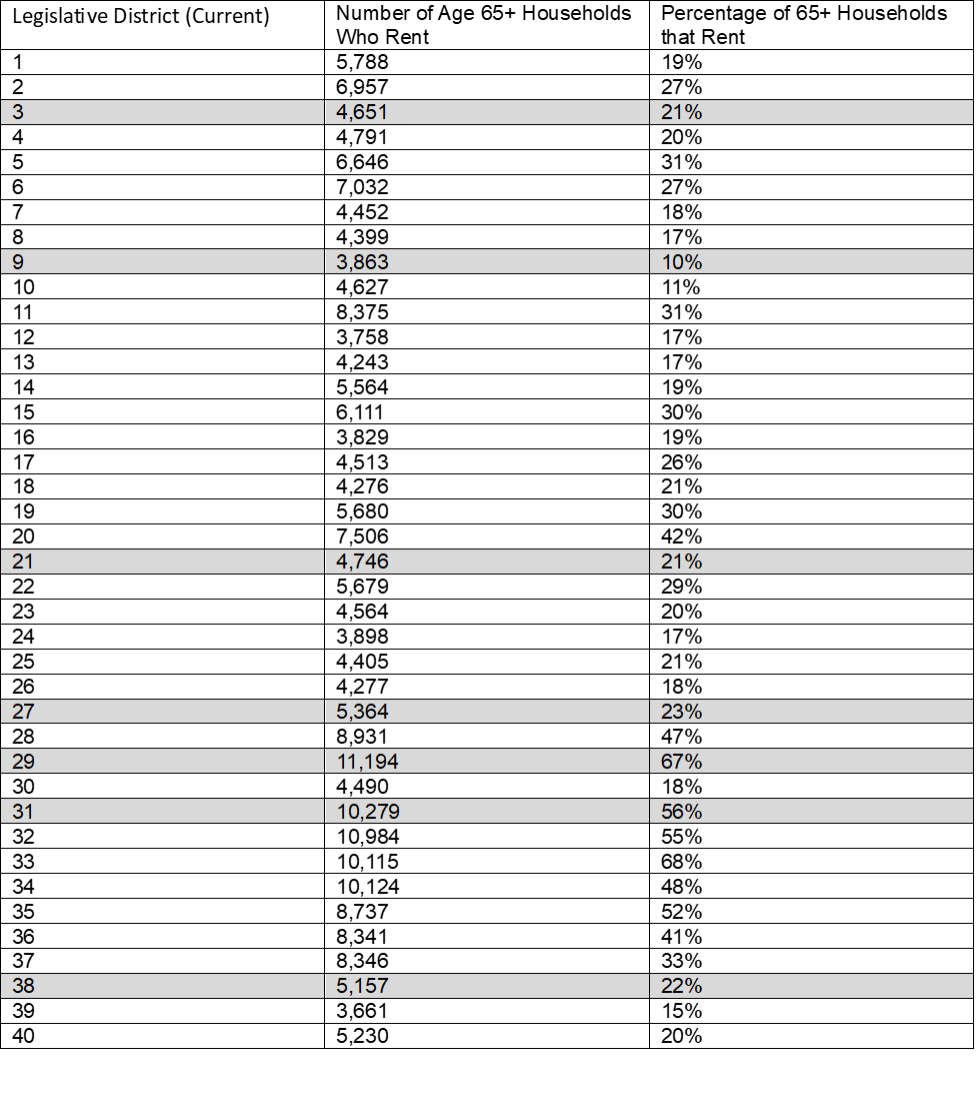

On top of these risky corporate tax changes, the budget also incorporates the costly Stay NJ proposal, which provides a significant property tax credit to senior homeowners. If implemented fully, the program will cost approximately $1.7 billion, all of which is unfunded.[x] And due to its proposed structure benefiting wealthy homeowners, Stay NJ would overwhelmingly go to the highest-income households and would widen the state’s racial wealth gap.[xi]

As revenues already appear to be declining and spending continues to increase, wealthy corporations experiencing record profits have managed to pay less towards the state’s core investments and keep more for their shareholders and high-paid executives.

Red Flag 3: Unaddressed Fiscal Cliffs

While the new budget includes enough revenue and surplus funds to cover investments for FY 2024, looming funding gaps across various areas have been kicked down the road with no plans to address them. This includes fiscal cliffs from expiring federal pandemic assistance that has propped up local and county budgets, school districts, and state agencies that now anticipate major deficits in future years.[xii] Federal pandemic aid will have to be expended in the next few years, leaving a funding cliff when they expire.

Key programs facing cliffs include:

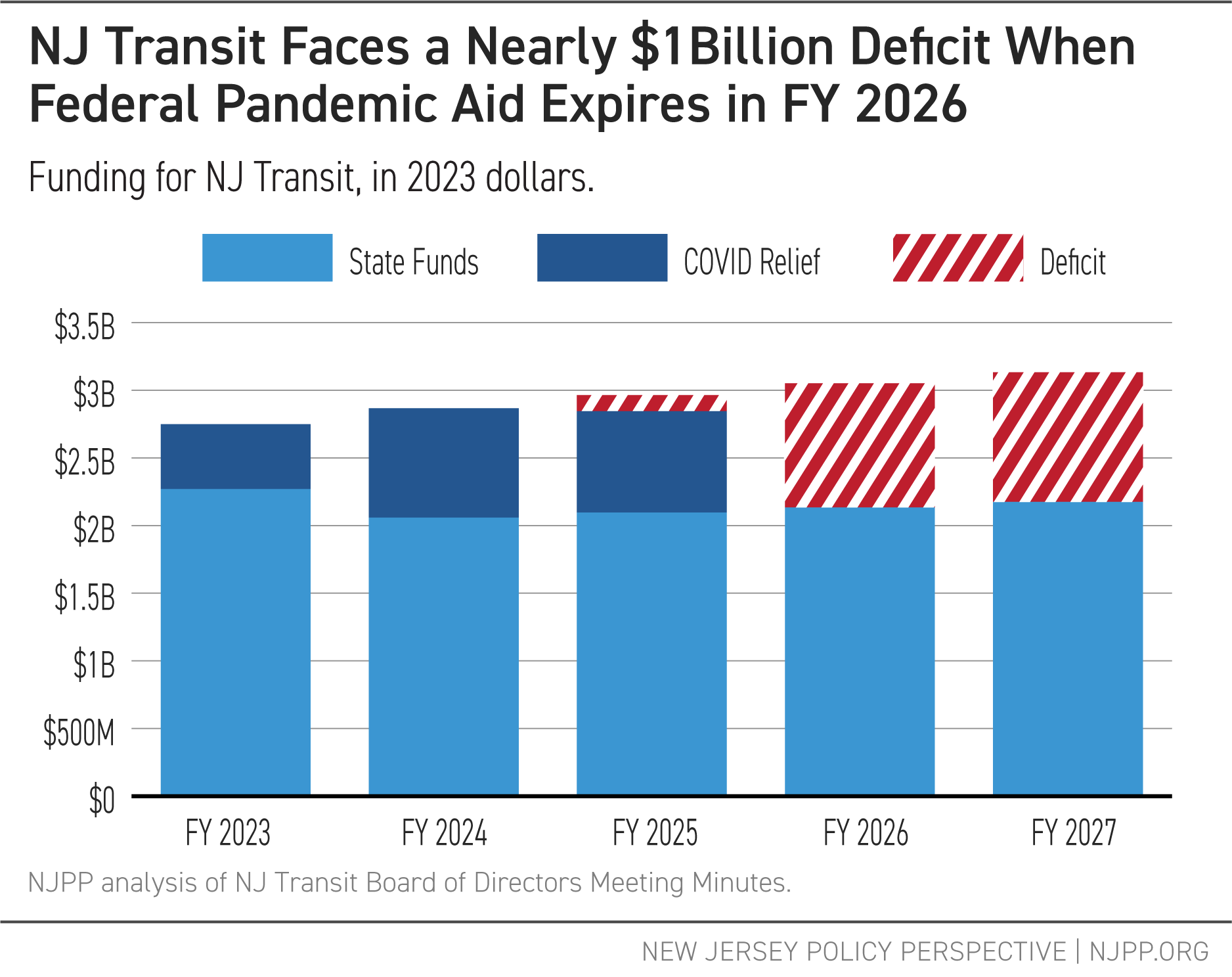

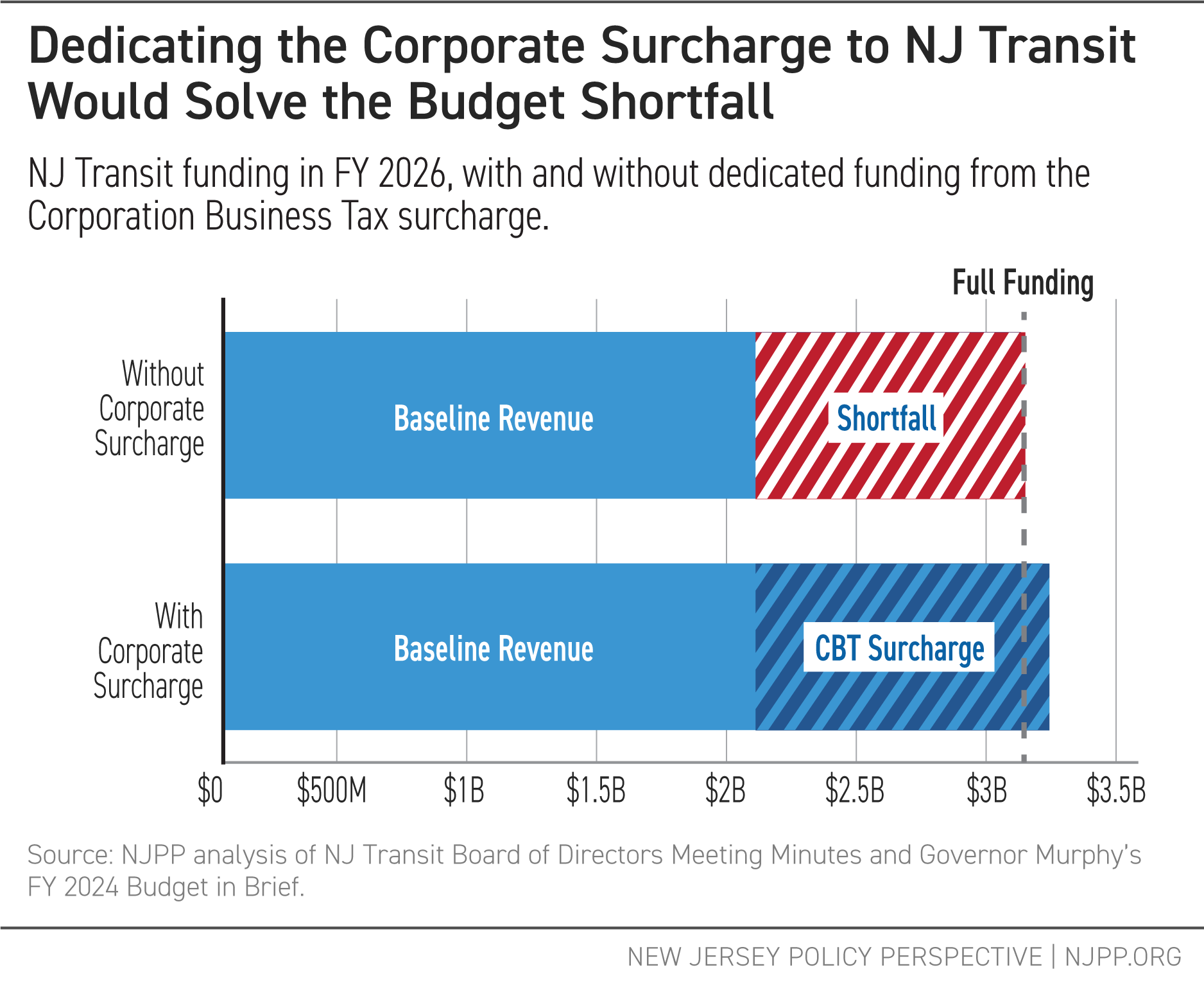

- NJ Transit: In FY 2025, NJ Transit, which does not have a sustainable funding source, has budgeted $749 million in federal relief. In FY 2026, that drops to $0.[xiii] Expiring federal aid, combined with lower fare collections, leave NJ Transit with a projected shortfall of roughly $1 billion in FY 2026.

- Child care: By September 2024, nearly $890 million in federal funds will expire, leaving the child care sector vulnerable to more closures.[xiv]

- K-12 schools: In September 2023, $1.2 billion in federal education funds will expire, followed by another $2.7 billion in September 2024.[xv] As it stands, the state currently does not fully fund its school funding formula.

Although these funds were designed to be temporary, a failure to replace them with sustainable state funding could lead to harmful cuts that would hamstring New Jersey’s economy and damage the very assets that make the state a great place to live, raise a family, and start a business: infrastructure, education, and robust government services. Lawmakers will face difficult decisions sooner than they might like, as they must find new ways to continue funding these services or determine which ones to cut. Past experience has shown that when spending cuts come, they disproportionately harm Black and Hispanic/Latinx communities and low-income households.[xvi]

Sea of Green: Notable Investments and Budget Lines

Looking past the red flags, New Jersey’s FY 2024 budget includes many important investments in public services and programs that support New Jersey families, communities, and the broader economy. From tax credits for working families, to increased funding for education, to health insurance subsidies that increase access to comprehensive health care, the initiatives highlighted below are designed to uplift individuals and families across the state, raise the standard of living, and contribute to the future prosperity of the state.

Economic Security

Working Family Tax Credits

The New Jersey Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC) pay workers and their families money back in their tax returns, supporting strong families, reducing poverty, and helping to make New Jersey affordable for working- and middle-class households.

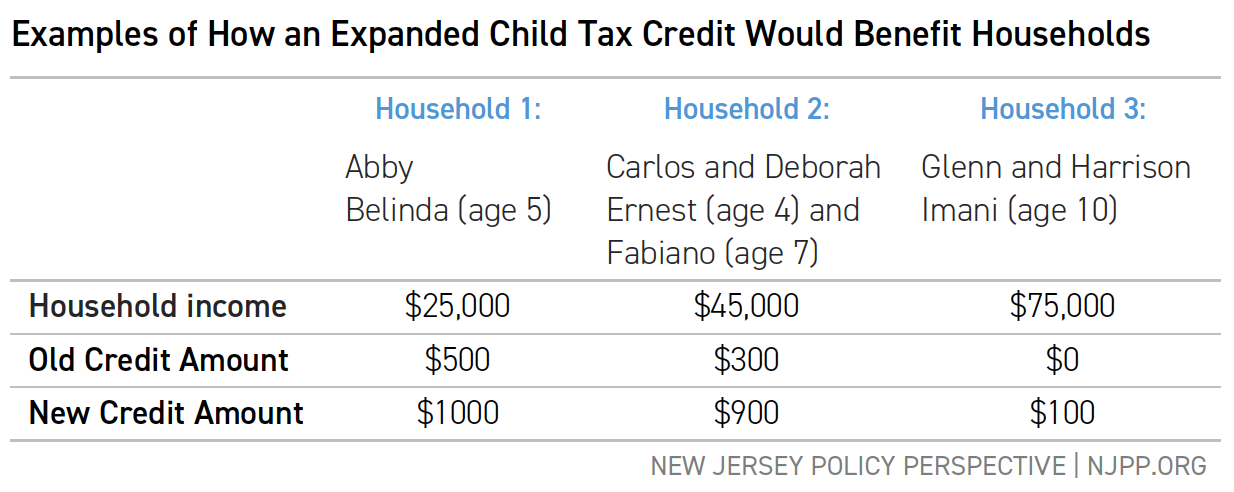

The FY 2024 budget doubles the Child Tax Credit (CTC), providing up to $1,000 for every child under age 6 to families earning up to $80,000, benefitting up to 372,000 children.[xvii] While the CTC expansion passed with overwhelming bipartisan support, and the increased credit is welcome news, the budget did not include a proposal to expand eligibility and access to the benefit for children up to 12 years old.[xviii]

It’s worth noting that the cost of the CTC expansion, roughly $120 million, pales in comparison to new tax credits for businesses included in the budget. Film and television studios alone will receive more than $230 million in new tax credits in FY 2024.[xix]

The FY 2024 budget also leaves the EITC unchanged, despite pending legislation to reduce barriers in the program and increase benefit levels to further boost workers’ wages.[xx] To better support working families struggling with rising living costs, lawmakers should increase the EITC to 50 percent of the federal credit and expand eligibility to immigrants with Individual Tax Identification Numbers. These changes would get more money back into the pockets of families who need it, reducing poverty and strengthening local economies across the state.

WorkFirst NJ

New Jersey’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, WorkFirst NJ, is supposed to provide basic financial support to very low-income households. While it is well-known that this program is underfunded and falls short for low-income families, the FY 2024 budget failed to increase WorkFirst NJ benefits.[xxi] The current grant amount — the maximum benefit is $559 a month for a family of three — remains far too low to meet the program’s goal of helping families afford their most basic needs.[xxii] For this program to succeed at helping families get by and break the cycle of poverty, lawmakers must commit to raising WorkFirst NJ benefits, reworking the program to meet the realities of today’s families, and moving TANF away from its racist “welfare reform” roots.[xxiii]

Education

The FY 2024 budget continues to bring New Jersey closer to fully funding the state’s school funding formula, investing $11 billion in K-12 education, which includes $103 million in stabilization aid for school districts facing cuts.[xxiv] This is an increase of more than $800 million compared to the prior year. This increase, as well as those made throughout Governor Murphy’s tenure, are critical to ensuring that New Jersey meets its constitutional obligation to fully fund education. Pre-kindergarten funding also received a boost of $116 million over the prior year, bringing New Jersey closer to its statutory goal of universal preschool.[xxv]

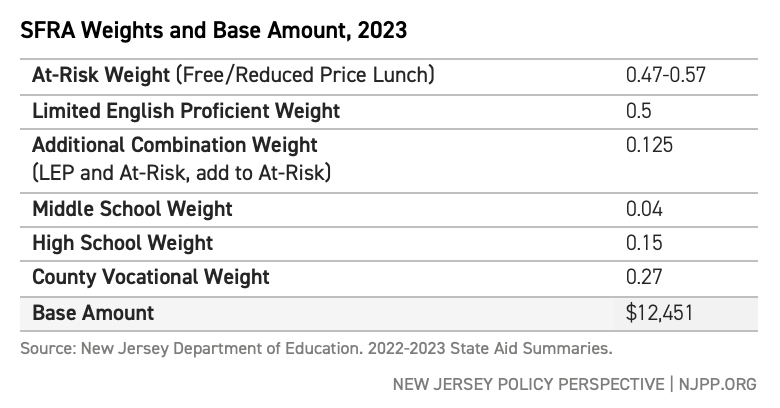

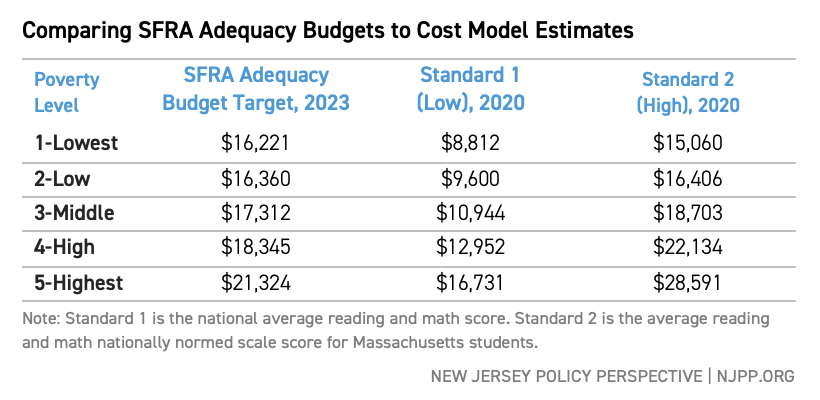

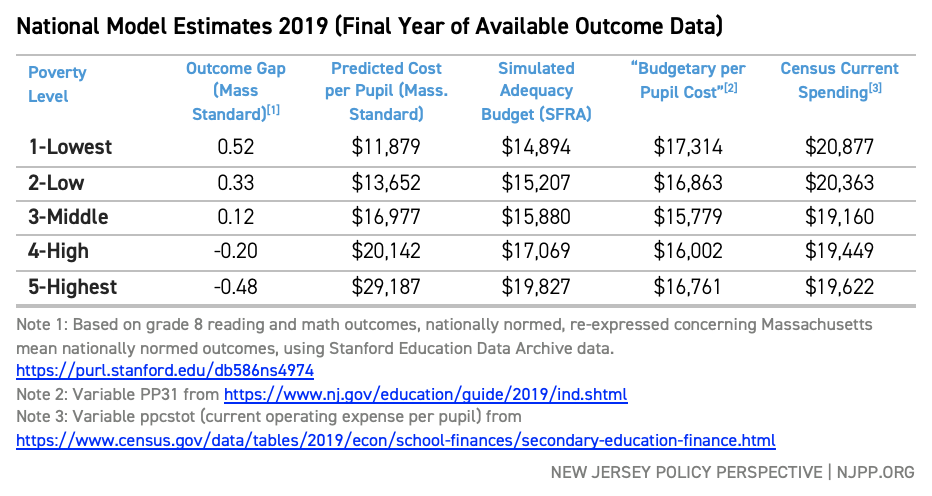

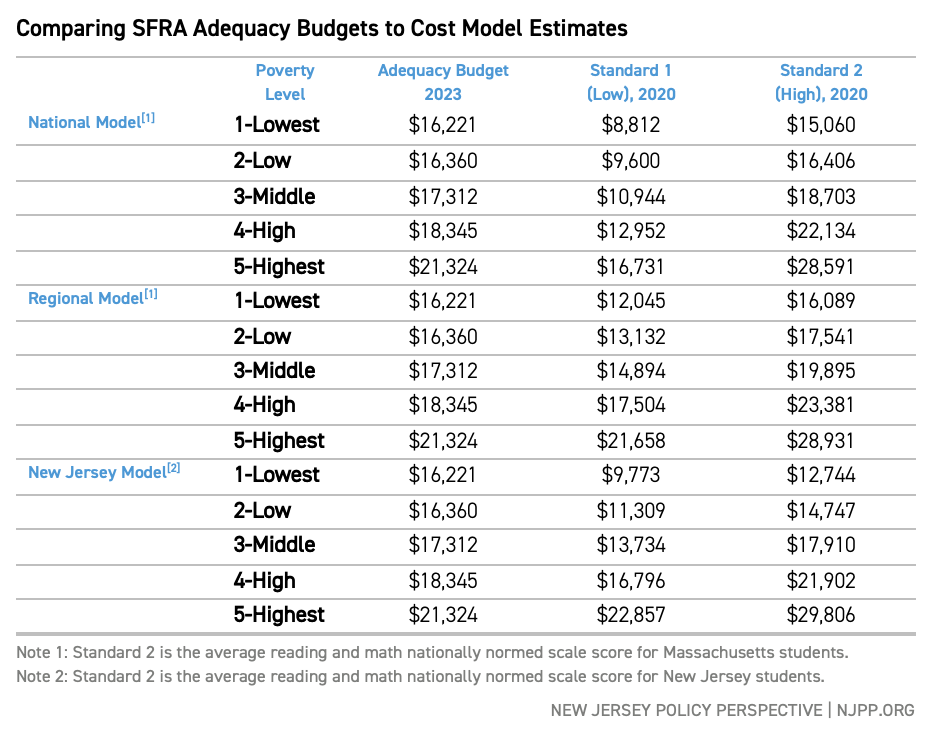

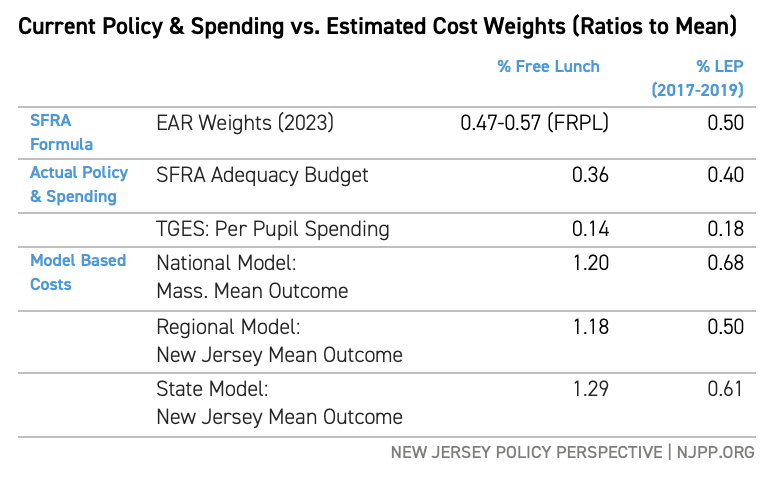

The number of children attending schools that receive less than adequate aid under the formula has reduced substantially since 2015.[xxvi] However, there is evidence that the School Funding Reform Act (SFRA) targets are too low to meet New Jersey’s current and more rigorous educational standards.[xxvii] While fully funding the school funding formula remains an important short-term goal, resetting its adequacy targets to meet the new, higher outcome standards must become a priority for lawmakers.

Health

Cover All Kids

Cover All Kids is a hallmark achievement of the Murphy administration, with all income-eligible children now able to receive public health insurance, regardless of immigration status.[xxviii] This initiative reduces barriers to health care and is responsible for recent progress in lowering the number of uninsured children across the state.[xxix] The FY 2024 budget includes $14.1 million for this initiative.[xxx] It is unclear how much of last year’s funding will carry forward, and the program’s continued success will require ongoing investments to maintain outreach and enrollment efforts. The budget also includes language allowing the state to explore affordable health insurance options for all children, regardless of immigration status, who are not income-eligible for NJ Family Care, closing the final implementation gaps and providing universal coverage for all kids in New Jersey.[xxxi]

Health Insurance

Over the last few years, increased health insurance subsidies have helped get a record number of people insured, and the FY 2024 budget continues to invest $25 million to support health insurance marketplace subsidies.[xxxii] However, with the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency, many people will likely lose their public health insurance coverage, forcing them to find coverage elsewhere.[xxxiii] It’s unclear whether flat funding will be sufficient to maximize coverage.

Medical Debt Relief

The burden of medical debt has widespread consequences on the economic stability of individuals and families. The FY 2024 budget includes a novel pilot program with a $10 million investment of pandemic relief funds to assist families reduce their medical debt.[xxxiv] This program will focus on helping low- and middle-income residents, with eligibility limited to residents who have a household income below 400 percent of the federal poverty level ($99,440 for a family of three in 2023) or have medical debt equal to 5 percent or more of the household’s income.[xxxv] Although details on the program are still forthcoming, similar programs in other states have helped eliminate residents’ medical debt for pennies on the dollar.[xxxvi]

Reproductive Health

Last year, Governor Murphy signed legislation to codify abortion rights in New Jersey, solidifying the state’s commitment to protecting the right to reproductive freedom.[xxxvii] The FY 2024 budget reaffirms this commitment with a $10 million investment to increase reimbursement rates for reproductive health care providers.[xxxviii] This will help support clinics and health care professionals currently overwhelmed and under-resourced, serving New Jersey and out-of-state residents seeking a safe haven in the Garden State.[xxxix] The budget also continues to invest in family planning services through the state’s Department of Health with a $30 million allocation.[xl] Similarly, the new initiatives from last year’s budget to address the post-Dobbs threats to reproductive health — for training OBGYNs, facilities upgrades, and security needs — are maintained at $20 million. [xli]

To build on the state’s recent successes in reproductive health, lawmakers must consider expanding access to abortion care for uninsured and underinsured residents just as the state does for other prenatal care.[xlii]

Maternal Health

Funding in the FY 2024 budget also reflects the Murphy administration’s commitment to addressing New Jersey’s wide racial disparities in maternal and infant health. The budget includes a $200,000 investment in the Restorative Maternal Health Birthing Center in Trenton.[xliii] Additionally, the budget includes a $4.5 million increase in funding for the Universal Home Visiting program, which entitles all parents with newborn infants to at least one free postpartum home visit.[xliv] The program will receive a total of $15.6 million for FY 2024.[xlv]

Prescription Drugs

The high cost of prescription drugs has reached crisis levels: Nearly a quarter of New Jersey residents have not taken medicine as prescribed due to concerns about cost.[xlvi] The FY 2024 budget takes initial steps toward addressing this urgent issue. Thanks to new laws and investments in the budget, residents will see EpiPen, insulin, and asthma inhaler costs capped on certain state-regulated insurance plans, in addition to lower prices at the pharmacy for some medications, depending on their insurance plan, in the coming months.[xlvii] The budget also includes expanded affordability measures for seniors on Medicare.[xlviii]

The budget also created the Drug Affordability Council (DAC) to bring transparency to the pharmaceutical industry. The DAC will research the underlying factors behind high drug costs and make recommendations to lawmakers on ways to further rein in costs and make prescription drugs affordable for more residents.[xlix] State leaders will need to provide sufficient support for the DAC and act quickly on its recommendations to lower prescription drug prices further.

Harm Reduction Services

Harm reduction services are essential to support people who use drugs, keep people out of the criminal legal system, and promote long-term health and public safety. The FY 2024 budget maintains funding levels for existing harm reduction centers at $4.5 million.[l] In supporting the expansion of local harm reduction centers, the new harm reduction center operated by Black Lives Matter Paterson will receive a grant for $250,000.[li] There is also funding for expanded access to naloxone, so pharmacies across the state can provide the life-saving drug anonymously and for free.[lii] Separate from the state budget, New Jersey will receive $600 million over the next two decades from settlements with opioid manufacturers, which should be allocated to harm reduction service expansion and healing the harms of the War on Drugs.[liii]

Public Safety

Public Defender Fees

The constitutional right to counsel guarantees legal representation for those accused of a crime, regardless of their ability to pay. Until now, one’s right to legal representation from a state-issued public defender in New Jersey came with a price tag, sometimes in excess of $1,000.[liv] These high fees not only contributed to the cycle of poverty but also created perverse incentives for defendants, as accepting a plea bargain came with lower fees than fighting a case. The latest state budget eliminates state-level public defender fees — a huge win for the residents of New Jersey and a major step toward a more equitable justice system for all.

The FY 2024 budget appropriates $4.4 million to both cover the costs of public defender fees and provide modest pay increases for attorneys that assist the Office of the Public Defender (OPD).[lv] The Legislature also repealed the statute requiring fees and wiped out existing liens owed to the OPD.[lvi]

Unfortunately, municipal and county-level public defenders may still require fees for service. Eliminating public defender fees across the board is the logical next step for state lawmakers, as access to a constitutional right should not exist behind a paywall and result in debt.

Crisis Response and Violence Intervention Programs

The current approach to public safety, premised on punishment and rooted in racism, often falls short of keeping residents safe, while doing active harm to Black and brown communities through over-policing and unnecessary use of force. This was exemplified by the tragic death of Najee Seabrooks, who was shot and killed by Paterson Police earlier this year while experiencing a mental health crisis. Mental health crises are one of many situations where armed police are not the best equipped to respond. Even so, legislation that would have provided $10 million to fund new community-led crisis response teams did not make it into the final state budget, as the bill passed through the Assembly but has yet to be heard in the Senate.[lvii]

However, the state budget continues to invest in community-led violence intervention programs, which help resolve high-risk conflicts and disputes, connecting residents to needed supports and keeping them out of the criminal legal system. The FY 2024 budget includes $15 million — $10 million from the state and $5 million in federal funds — to support and expand the state’s existing community-based violence intervention programs.[lviii] Community-led responses are an evidence-based approach to improve public safety, centering restorative justice and harm reduction without resorting to armed police response.[lix]

In stark comparison, the FY 2024 budget includes far-greater investments in conventional policing across the state. Some examples include: Camden County Metro Police received $8 million for technology upgrades,[lx] the police headquarters in the Borough of Haddonfield received $5 million,[lxi] and the Paterson Police Department received $10 million.[lxii] Additionally, ARRIVE Together, the Attorney General’s crisis response initiative operated by State Police, receives roughly $10.6 million.[lxiii]

As the need for a non-police response to crises becomes increasingly evident, future budgets should prioritize funding for more community-based solutions.

Environment and Transit

Clean Energy Fund

New Jersey’s Clean Energy Fund aims to help the state transition to 21st-century technologies that reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, cut air pollution, and save families money. However, more than $2 billion has been raided from the fund over the last decade, including $70 million in the new state budget.[lxiv] This is a minor improvement compared to the raid in last year’s budget, but every dollar raided makes it less likely New Jersey will meet its ambitious clean energy goals. If used as intended, the Clean Energy Fund will drive investments in areas like offshore wind and bus electrification, reducing air pollution and creating good-paying jobs across the state.

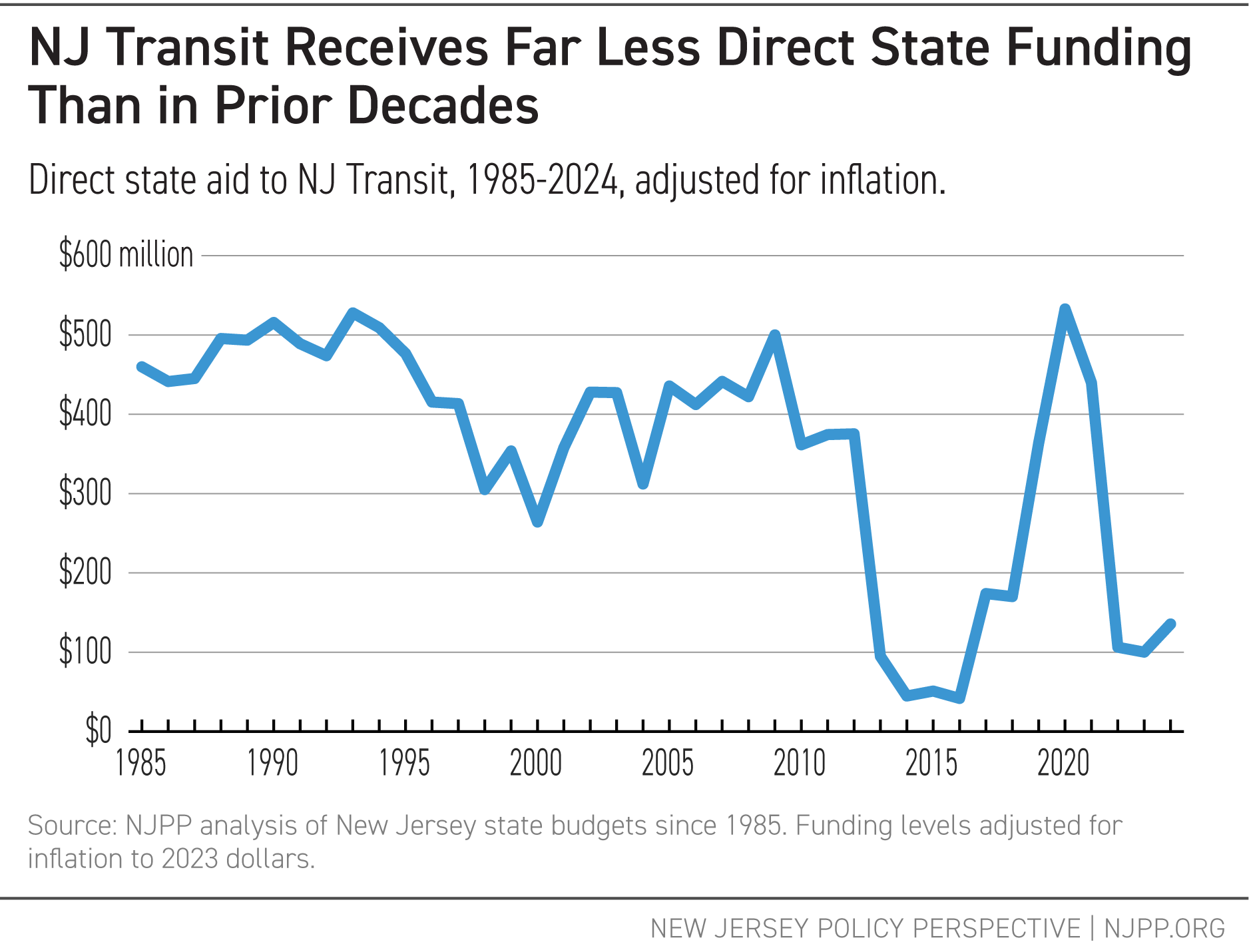

NJ Transit

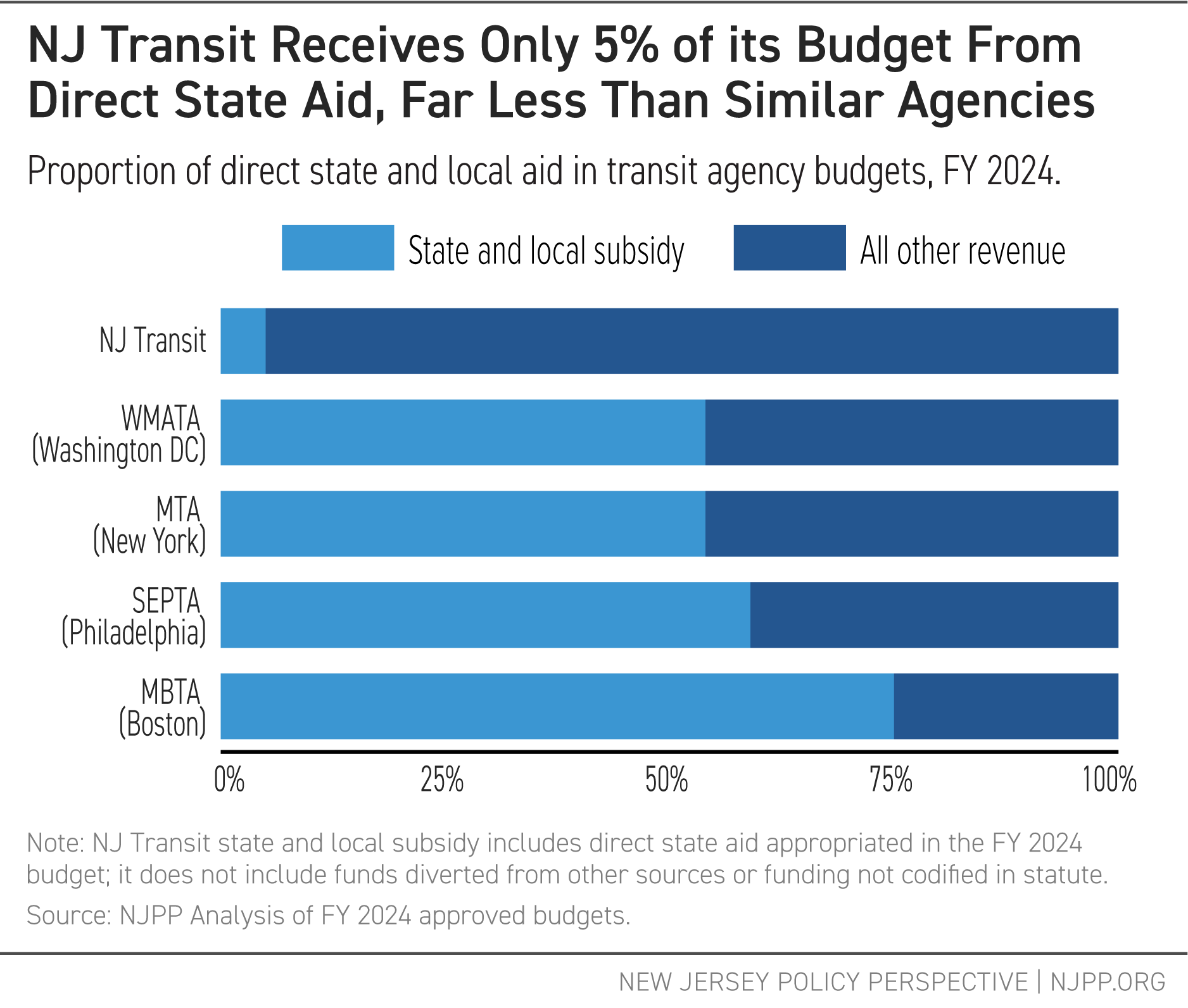

NJ Transit is a cornerstone of mobility in New Jersey, providing residents with transportation to their jobs, doctors, schools, and more. But years of underfunding have left NJ Transit in a state of disrepair and passengers without a reliable source of transportation. The FY 2024 budget contains $2.87 billion for NJ Transit with no new fare hikes, but that does not tell the whole story.[lxv] The transit agency’s budget relies on expiring federal funds, diversions from the Clean Energy Fund, and it once again diverts NJ Transit’s capital funds to cover operating costs, transferring $334 million to cover routine maintenance.[lxvi] Without additional state funding, NJ Transit faces a $1 billion deficit by FY 2026 due lower than expected fare collections and federal pandemic assistance about to expire.[lxvii]

NJ Transit remains the only transit agency of its size in the United States without a reliable, dedicated funding source. If lawmakers do not act quickly to fully fund NJ Transit, the state may experience a transit death spiral, with drastic service cuts, fare hikes, and breakdowns that leave passengers stranded.[lxviii]

Conclusion: Sustainable Investments Need Sustainable Revenues

The investments made in New Jersey’s FY 2024 will pay great dividends in years to come. But sustainable tax revenue is required to maintain and build on these investments in future years. With tax collections already declining, even a small economic downturn could lead to reduced revenues that throw the state budget out of balance. Coupled with costly tax cuts and expiring federal pandemic relief funds, lawmakers may soon face difficult choices and potentially devastating cuts to programs and services.

A period of economic uncertainty is not the time to cut taxes for billion-dollar corporations or to direct tax giveaways to wealthy individuals and special interests. A strong tax code where those with the most pay what they owe is the only way to guarantee the promise of the budget’s investments for years to come.

End Notes

[i] The final approved appropriations in the FY 2024 Appropriations Act was $54,319,047,000 after the Governor’s line-item veto. See Governor Philip Murphy, Veto Message and Summary, A5669/S2024 (June 30, 2023), p. 2, https://d31hzlhk6di2h5.cloudfront.net/20230630/07/c4/38/35/b3a57fbddd9e9af6a3e5a3bd/FY2024_Veto_Message_and_Summary.pdf.

[ii] New Jersey Department of the Treasury, State of New Jersey, Month and Year-to-Date Cash Collections, Fiscal Year 2023 – May 2-23 versus 2022 (June 19, 2023), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/news/2023/pdf/MonthlyReport%20with%20Snapshot-FY23May.pdf.

[iii] See Office of Legislative Services, FY 2024 Appropriations Bill Scoresheet, June 30, 2023, p.1 https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/Scoresheet,%20As%20Introduced.pdf.

[iv] Justin Theal & Alexandre Fall, Record State Budget Reserves Buffer Against Mounting Fiscal Threats, Pew Charitable Trusts, March 22, 2023, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/03/16/record-state-budget-reserves-buffer-against-mounting-fiscal-threats.

[v] Sheila Reynertson, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Don’t Forget to Fix New Jersey’s Shrinking Rainy Day Fund, July 19, 2017,

https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/lets-not-forget-to-fix-new-jerseys-shrinking-rainy-day-fund/.

[vi] The Governor’s FY 2024 Budget in Brief, hereinafter “FY 2024 Budget in Brief”, February 2023, p. 65, https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/omb/publications/24bib/BIB.pdf. The FY 2024 Budget in Brief is cited when budget allocations do not appear as specific line items in the Appropriations Act, Assembly Bill 5669, hereinafter “FY 2024 Appropriations Act.”

[vii] Sheila Reynertson, Stop the Sunset: Corporate Tax Cut Would Benefit the Biggest and Most Profitable Businesses, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Feb. 22, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/stop-the-sunset-corporate-tax-cut-would-benefit-the-biggest-and-most-profitable-businesses/.

[viii] Peter Chen, New Jersey Policy Perspective, GILTI as Charged: New Corporate Tax Proposal Would Accelerate Tax Avoidance, April 6, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/gilti-as-charged-new-corporate-tax-proposal-would-accelerate-tax-avoidance/.

[ix] For more on this trend nationally, see Josh Bivens, Economic Policy Institute, Reclaiming Corporate Tax Revenues, April 14, 2022, https://epi.org/247534.

[x] Assembly Budget Committee Statement to Assembly Bill No. 1, June 28, 2023, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/A1/bill-text?f=A0500&n=1_S2.

[xi] Peter Chen, New Jersey Policy Perspective, StayNJ 2.0: Senior Tax Cut Still 2 Regressive and 2 Expensive, Jun. 27, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/staynj-2-0-senior-tax-cut-still-2-regressive-and-2-expensive/.

[xii] The Treasurer’s May Supplemental Budget Update showed total revenues of $52.8 billion in FY 2023, compared to $54.6 billion in expenditures. See New Jersey Department of the Treasury, FY 2024 Budget, May 17, 2023, p. 3, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/news/2023/pdf/TreasurersMayPacket.pdf. However, additional associated bills not included in the FY 2024 Appropriations Act, notably the Stay NJ property tax credit program, increased the total cost of the budget to $54.5 billion. See Press Release, Governor Phil Murphy, Governor Murphy Signs Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Into Law, June 30, 2023, https://nj.gov/governor/news/news/562023/approved/20230630f.shtml.

[xiii] New Jersey Transit Budget Proposal Transmittal, April 19, 2023, at Exhibit B, appendix D, p. 41, https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/board/meeting_minutes/2023_04_19_OpenSessEXP.pdf.

[xiv] Linda Smith & Victoria Owens, Bipartisan Policy Center, States Face a $48 Billion Child Care Funding Cliff, June 3, 2022, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/states-face-a-48-billion-child-care-funding-cliff/.

[xv] New Jersey Department of Education, Text Version: New Jersey One-Time Grants and Timelines Charts, (June 22, 2022), https://www.nj.gov/education/federalfunding/understanding/TextVersion_OneTimeGrants.shtml.

[xvi] For a summary of how economic austerity during the Great Recession harmed racial and economic equity, see Asha Banerjee & Emma Williamson, Center for Law and Social Policy, Fighting Austerity for Racial and Economic Justice, October 2020, https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2020_Fighting-Austerity-for-Racial-and-Economic-Justice.pdf.

[xvii] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p.13; Office of Legislative Services, Fiscal Note, Senate, No. 3940, June 23, 2023, https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/Bills/2022/S4000/3940_F1.PDF.

[xviii] Assembly Bill 3857, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/A3857.

[xix] Peter Chen & Pat Garofalo, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Reel Regret: The High Cost of Expanding Film Tax Credits in New Jersey, June 26, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/reel-regret-the-high-cost-of-expanding-film-tax-credits-in-new-jersey/.

[xx] Senate Bill 2458, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/S2458.

[xxi] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 141, lines 31-33.

[xxii] New Jersey State Plan for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) FY 2021-2023, at attachment B, https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dfd/programs/workfirstnj/tanf_2021_23_st_plan.pdf; Raymond Castro, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Promoting Equal Opportunities for Children Living in Poverty, April 13, 2020, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/promoting-equal-opportunities-for-children-living-in-poverty/.

[xxiii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance.

[xxiv] Press Release, Governor Murphy Signs Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Into Law, June 30, 2023, https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562023/20230630f.shtml.

[xxv] Press Release, Governor Murphy Signs Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Into Law, June 30, 2023, https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562023/20230630f.shtml.

[xxvi] Mark Weber & Bruce Baker, New Jersey Policy Perspective, School Funding in New Jersey: A Fair Future for All, November 17, 2020, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/school-funding-in-new-jersey-a-fair-future-for-all/.

[xxvii] Bruce Baker & Mark Weber, New Jersey Policy Perspective, New Jersey School Funding: The Higher the Goals, the Higher the Costs, February 2, 2022, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/new-jersey-school-funding-the-higher-the-goals-the-higher-the-costs/.

[xxviii] Pub. L. 2021, c. 132.

[xxix] New Jersey Department of Human Services, Response to OLS Questions, FY 2024 Budget, p. 9, https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/governors-budget/2024/DHS_response_2024.pdf.

[xxx] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 33.

[xxxi] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 30.

[xxxii] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 29.

[xxxiii] New Jersey Department of Human Services, Stay Covered NJ, Eligibility Unwinding, 2023, https://nj.gov/humanservices/dmahs/staycoverednj/unwinding/. Last accessed July 2023. Page on file with author.

[xxxiv] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 275, line 36.

[xxxv] United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2023 Poverty Guidelines, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1c92a9207f3ed5915ca020d58fe77696/detailed-guidelines-2023.pdf; FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 275, lines 55-74.

[xxxvi] Amanda Holpuch, Medical Debt Is Being Erased in Ohio and Illinois. Is Your Town Next?, New York Times, Dec. 29, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/29/us/toledo-medical-debt-relief.html.

[xxxvii] Pub. L. 2021, c.375.

[xxxviii] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 126, lines 36-41.

[xxxix] Heather Howard, New Jersey should increase Medicaid reimbursement rates for reproductive health care, New Jersey Globe, May 15, 2023, https://newjerseyglobe.com/health/opinon-new-jersey-should-increase-medicaid-reimbursement-rates-for-reproductive-health-care/.

[xl] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 95, line 47. The Family Planning Services line-item was funded at $19,529,000 in FY 2022 and $30,029,000 in FY 2023. See FY 2024 Governor’s Detailed Budget, p. D-159, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/24budget/FY2024BudgetDetail-Full.pdf.

[xli] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 163, p. 96, line 4, p. 160, line 35.

[xlii] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 121, lines 31-39.

[xliii] Lilo Stainton, Not one, but two birthing centers in the works for Trenton, NJ Spotlight, October 26, 2022, https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2022/10/two-trenton-birthing-centers-maternal-infant-health-mortality-tammy-murphy/; FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 44, p. 202, lines 14-16.

[xliv] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 29.

[xlv] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 31.

[xlvi] Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, New Jersey Residents Worried about High Drug Costs; Support a Range of Government Solutions, 2023, https://healthcarevaluehub.org/advocate-resources/publications/new-jersey-residents-worried-about-high-drug-costs-support-range-government-solutions-1.

[xlvii] P.L.2023, c. 105. Bill text is available at https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/S1614.

[xlviii] P.L.2023, c. 79. Bill text available at https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/S3.

[xlix] P.L.2023, c. 106.

[l] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 96, line 33; FY 2024 Governor’s Detailed Budget, p. D-161.

[li] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 96, line 32.

[lii] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 38.

[liii] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 38.

[liv] Marleina Ubel, New Jersey Policy Perspective, The High Cost of “Free” Representation: Why New Jersey Should Eliminate Public Defender Fees, October 24, 2022, https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/the-high-cost-of-representation-public-defender-fees/; Marea Beeman et al., National Legal Aid and Defender Association, At What Cost? Findings from an Examination into the Imposition of Public Defense System Fees, July 2022, pp. 98-99, https://www.nlada.org/sites/default/files/NLADA_At_What_Cost.pdf?v=2.0.

[lv] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 41.

[lvi] P.L.2023, c. 69.

[lvii] Assembly Bill 5326, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/A5326.

[lviii] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 39.

[lix] New Jersey Policy Perspective, To Protect and Serve: Investing in Public Safety Beyond Policing, October 13, 2021, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/to-protect-and-serve-investing-in-public-safety-beyond-policing/

[lx] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 52.

[lxi] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 49.

[lxii] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 159, line 35.

[lxiii] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 156, line 50, p. 153, line 34.

[lxiv] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p. 99; Alex Ambrose, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Stop the Raids: The Clean Energy Fund Should Fund Clean Energy, Jan. 12, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/stop-the-raids-the-clean-energy-fund-should-fund-clean-energy/.

[lxv] FY 2024 Budget in Brief, p 43.

[lxvi] FY 2024 Appropriations Act, p. 271, lines 19-20.

[lxvii] NJ Transit Board Minutes, April 20, 2023, appendix D, p. 41. https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/board/meeting_minutes/2023_04_19_OpenSessEXP.pdf.

[lxviii] Elise Young, NJ Transit’s Creaky, Empty Trains Stir Worry of Fare Increases, Bloomberg, Feb. 24, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-24/nj-transit-delays-hit-record-high-despite-gov-murphy-pledge-to-fix-trains.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Demographic and Housing Characteristics Table H13

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Demographic and Housing Characteristics Table H13