When Gov. Christie took office in 2010, he had his work cut out for him. New Jersey’s economy was in the depths of the Great Recession, throwing an already fragile state budget into deeper crisis. In his first budget address, he promised to fix the state’s budget crisis, revamp the public pension system and reduce overall state spending without using “gimmicks or band-aids.” But as we look toward the governor’s final budget of his eight-year tenure, it’s clear that New Jersey’s financial crisis persists.

A weak economic recovery, on top of big tax cuts and breaks that have helped lead to chronic revenue shortfalls, and ongoing battles over pension obligations, have led the state’s credit rating to be downgraded a record 10 times during Gov. Christie’s tenure. Despite a huge increase in corporate tax breaks, New Jersey has yet to recover jobs at a rate anywhere near those of neighboring states or the nation as whole. New Jersey has the eighth slowest post-Recession revenue growth rate of the states and only nine days of operating funds on reserve – the 5th lowest of the states – putting the state in serious jeopardy should another recession or disastrous storm sink the economy.

As he prepares to present his final state budget this month, the list of enormous and unresolved issues facing New Jersey’s finances – and its prosperity – is as varied as it is daunting.

After uneven reform efforts, New Jersey’s pension system for retired public employees is now the most underfunded in the country. Despite a jump in annual payment size, contributions are actually 40 percent of what is recommended by actuaries to keep up with the ballooning obligations. Add to this crisis the state’s losing battle to adequately fund health care benefits for public employees. The pay-as-you-go method coupled with rising health care costs continue to cripple the state budget. New Jersey has underfunded state-mandated school aid for the past seven years. Now Gov. Christie wants to gut the school funding formula to give residents in wealthier districts a property tax break.

Meanwhile, New Jerseyans continue to pay the nation’s highest property tax bills. This year the average homeowner paid $8,459 – 2.2 percent higher than last year’s rate despite a 2 percent cap implemented by Gov. Christie. The average residential property tax bill was $7,281 in 2009 representing a 16 percent increase. At the same time, the number of New Jerseyans living below the federal poverty line has grown by 13 percent from 2009 to 2015. Today one in four New Jerseyans live in true poverty. Over one in ten New Jersey households did not have enough money to purchase food at some point last year.

Who wins, who loses

During Gov. Christie’s tenure, corporations and wealthy households have prospered the most, while those in the middle and those struggling to get by in the face of rising costs of living were largely left behind. The name of the economic-development game has largely been to offer tax subsidies to encourage businesses to relocate or stay in New Jersey.

Over the past 6 years, New Jersey has approved over $7 billion in ineffective tax subsidies to corporations – on top of $3 billion worth of business tax cuts it’s doled out.. Touted as a job-creating stimulus, these tax breaks have done little to boost the economy. New Jersey would need to add 120,000 jobs each year for the next three years just to get back to pre-recession levels and employ a growing population. But this past year, just 21,4000 jobs were added representing the 7th slowest job growth among the states since the start of the recession.

Over three-fourths of total income gained between 2010 and 2013 went to the top 35 percent of households. New Jersey now has the 7th highest level of income inequality in the country. That trend is sure to worsen as New Jersey phases out the estate tax, one of the best tools for reducing inequality and building broadly shared prosperity.

Revenue growth still unsteady

New Jersey’s tax collections have grown this fiscal year but at a slower pace than anticipated. If the lower growth rate continues, revenue may fall considerably short of what Office of Legislative Services (OLS) says is needed for the remaining months of this fiscal year.

If the current growth rate of 2.3 percent were to remain steady, the state budget could be over $950 million short in revenue. According to the latest figures from the OLS, the growth rate would need to be more than twice that rate to meet current costs and recover from the enormous tax cuts signed into law last fall. This lower-than-expected trend has plagued New Jersey since the Great Recession.

Overall, New Jersey’s tax collections continue to struggle to bounce back to pre-Recession levels. State tax collections in the second quarter of 2016 were still 10.9 percent lower than its peak in the fourth quarter of 2007. In fact, New Jersey is surrounded on all sides by states whose tax collections have long since recovered and grown. New York’s tax revenue, for example, was 12.7 percent higher in Q2 2016 than at its peak in Q3 2008. Pennsylvania’s tax revenue was 3.2 percent higher in Q2 2016 than at its peak in Q1 2008.

Given that revenue shortfalls continue to undermine the state’s ability to meet its obligations, the next budget is likely to resemble those from the last several years with expected underfunding in key areas including pension payments, school aid, tuition assistance for higher education and general assistance to families in need. Add to this strapped budget the loss of $675 million as a package of tax breaks begin to be phased in. That loss will increase to $1.4 billion by 2021. Some $350 million will no longer be diverted from the general fund to pay TTF debts, but in the long run, the state’s ability to adequately fund key obligations will be severely compromised due to these cuts.

Pension payments

Pension payments during Gov. Christie’s tenure may have been larger than those made by his predecessors, but they have been only a fraction of what is needed to keep the pension system from piling up even more debt.

After skipping a $3.1 billion payment in fiscal year 2011, Christie contributed $484 million in 2012, $1 billion in 2013 and $696 million in 2014. He then made a $892 million payment in fiscal year 2015 – nowhere near the $2.25 billion sought by the legislature. And the 2016 state’s contribution of $1.3 billion was also well below the $3.1 billion payment included in the legislature’s budget. For the fiscal year ending this June 30, the state’s contribution of $1.86 billion to the pension fund, which mirrors the Legislature’s contribution, will occur near the end of the fiscal year.

Recently, Gov. Christie announced a $650 million increase in state contributions to the pension fund boosting the total pension contribution for the 2018 fiscal year to approximately $2.51 billion in keeping with the state’s 10-year pension payment formula.

Higher education

New Jersey students and families continue to have a hard time affording the high cost of a college education, thanks in large part to sharply declining state support for public colleges and universities.

New Jersey has cut funding for higher education by 23 percent since 2008 when adjusted for inflation, a decrease of more than $2,250 per student and a deeper cut than the national average, according to a new report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). This is the 13th largest percentage decline, and 12th largest dollar decline, of the 50 states.

While many states are starting to reverse course and increase funding for higher education, New Jersey is going in the opposite direction. In fact, it is one of just 11 states where per-student funding fell from 2015 to 2016.

As a result of these cuts, the average tuition at a public, four-year college in New Jersey has increased by 17 percent, or $1,903, during this period. On top of these tuition increases, colleges and universities across the state have increased student fees, cut staff and faculty positions and offered fewer courses to save money. All this means that a degree takes much longer to attain, adding years of cost and debt.

Together, this means that most New Jersey’s families – already struggling with slow income gains if not reductions – are often paying more and incurring higher levels of debt for a lower-quality education. These post-recession increases come on the heels of large increases in tuition and fees at New Jersey’s public, four-year colleges in the early 2000s.

Looking ahead

It took New Jersey decades to dig itself into this fiscal hole and no one governor is going to fix it, but without a doubt it has gotten steadily worse over the past eight years. But it didn’t have to be this way given the proven tools that could have been employed to dig our way out. Here are a few examples of big, bold tools that the next administration should consider to help move New Jersey toward a more stable and prosperous future.

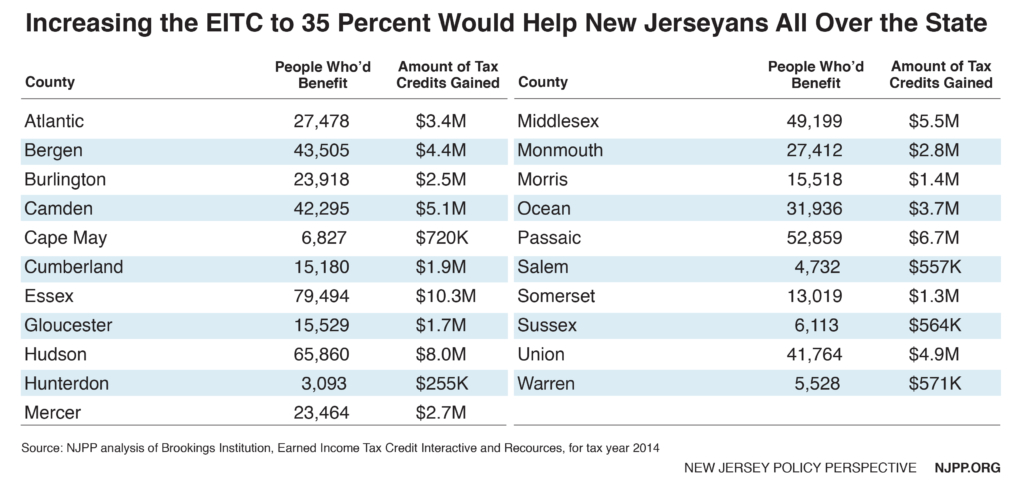

One of the most responsible ways to create a path to financial sustainability is to ensure that corporations and the wealthy are paying their fair share in New Jersey. Closing tax loopholes is one way to do this. Expanding combined reporting in New Jersey would close corporate loopholes and help prevent multi-state corporations from artificially shifting profits out of state. This tax policy could raise up to $290 million in much-needed revenue each year to shore up underfunded investments like higher education and public transit.

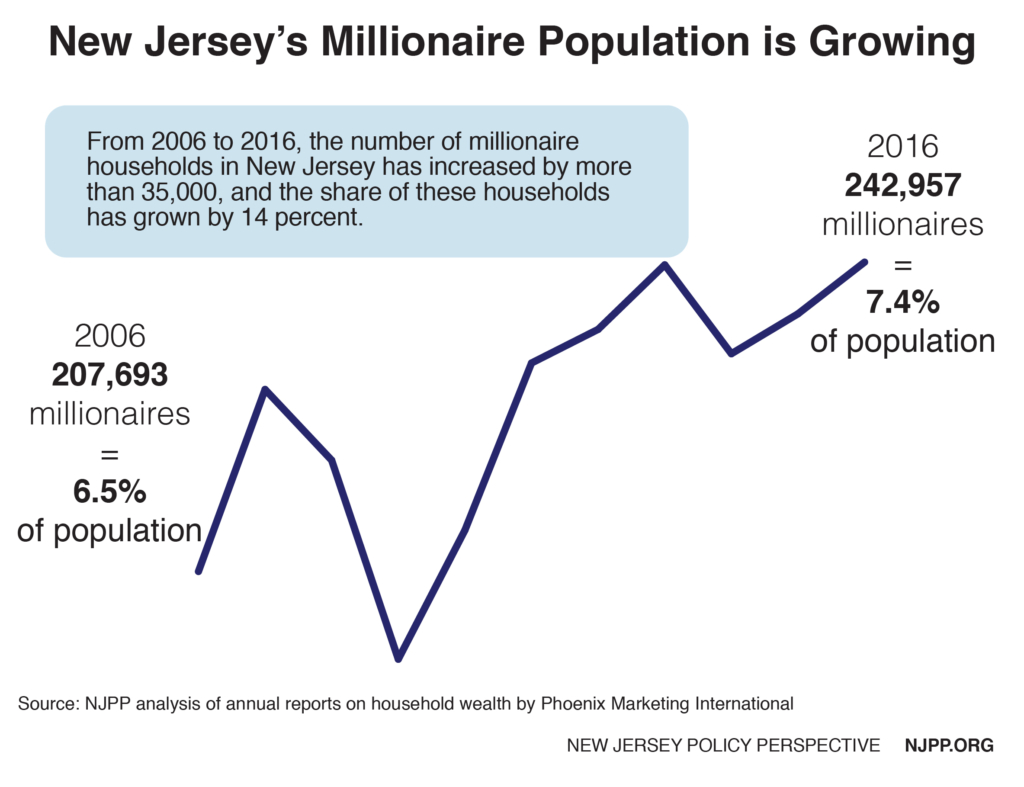

New Jersey is currently experiencing income inequality the likes not seen since the Gilded Age. The top 5 percent of New Jersey’s households have average incomes more than 15 times greater than the bottom 20 percent. As income inequality continues to rise, New Jersey has an opportunity to reinstate tax rates and expand tax brackets on wealthy households that have far and away done better than families struggling to get by. By doing so, New Jersey could raise more than $1 billion more each year.

One of the most progressive and equitable taxes in New Jersey, the estate tax, was actually a growing source of revenue before it was eliminated last fall. Paid for by just 5 percent of New Jersey estates in any given year, this long-standing tax on inherited wealth is now being phased out, giving heirs an average tax break of $140,000 and costing New Jersey about $500 million a year – an amount that was projected to grow significantly each year despite the drumbeat myth that the wealthy were fleeing New Jersey in droves.

Bringing the estate tax back even with higher threshold could significantly steer New Jersey in the right direction again. For instance, reinstating the estate tax on estates worth $2 million or more, could recover three-quarters of the lost tax revenue while restoring responsible and fair taxation of inherited wealth. Moreover, New Jersey’s inheritance tax could be modified to ensure that wealthy heirs pay their fare share while ending the tax on modest inheritances of $500.