Every child deserves a high-quality education, and every teacher who dedicates their career to this mission deserves financial security in retirement. Yet, in New Jersey, new teachers are getting a raw deal. As the state struggles with a growing teacher shortage, one major barrier to recruitment and retention is compensation — not just salaries, but also retirement benefits.

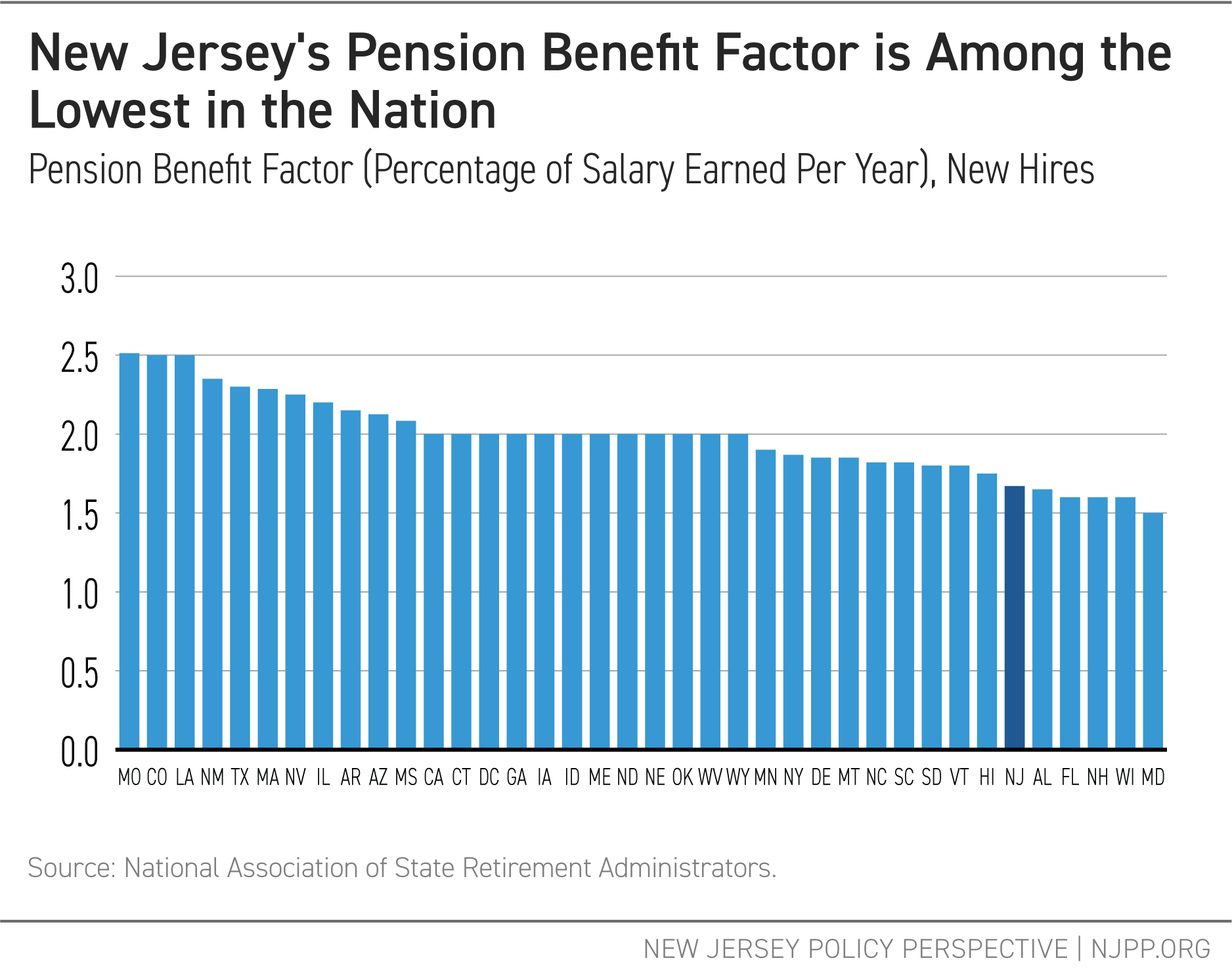

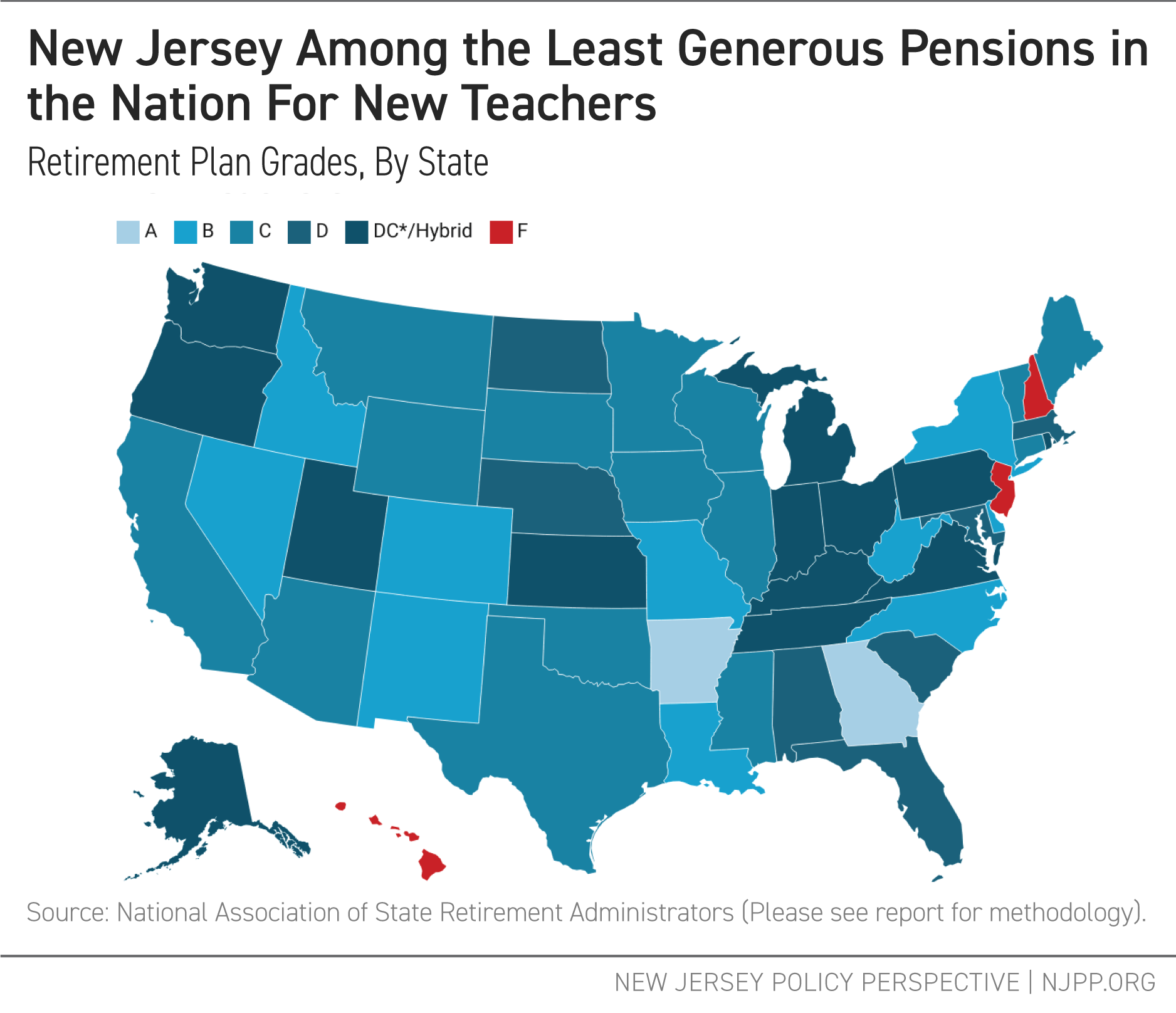

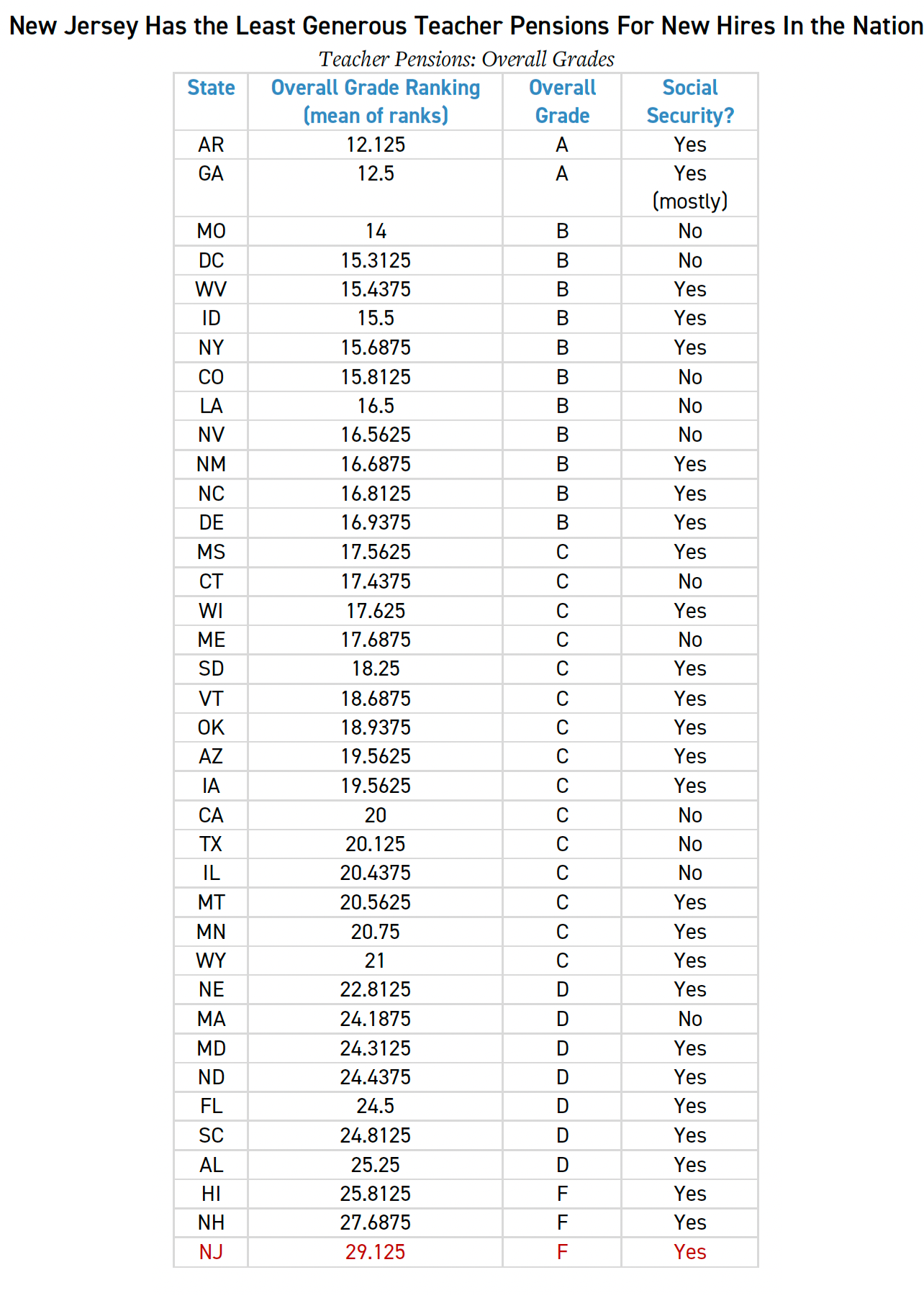

Compared to states with similar pension programs, New Jersey’s retirement benefits for newly hired teachers are the least generous in the nation. Among the 38 states with defined benefit pension plans for public school teachers, New Jersey ranks dead last. This is largely due to a combination of policy choices: a low “benefit factor” (the percentage of salary that accrues toward a pension each year), a high retirement age, a long vesting period, a lengthy average salary calculation period, and the absence of cost-of-living adjustments.

These shortfalls stem from policy changes made in 2011 through Chapter 78, which created a new pension tier (Tier 5) for teachers hired after that year. These changes raised contribution rates, increased the retirement age, and cut the value of benefits — leaving today’s teachers with the weakest defined benefit pension plans in the country.

If New Jersey wants to attract and retain the highly qualified, diverse educator workforce that students deserve, the state must reform its pension system. Eliminating Tier 5 and restoring fairer benefits would bring the state closer in line with national standards and help ensure that the teachers shaping our future can retire with dignity.

Background

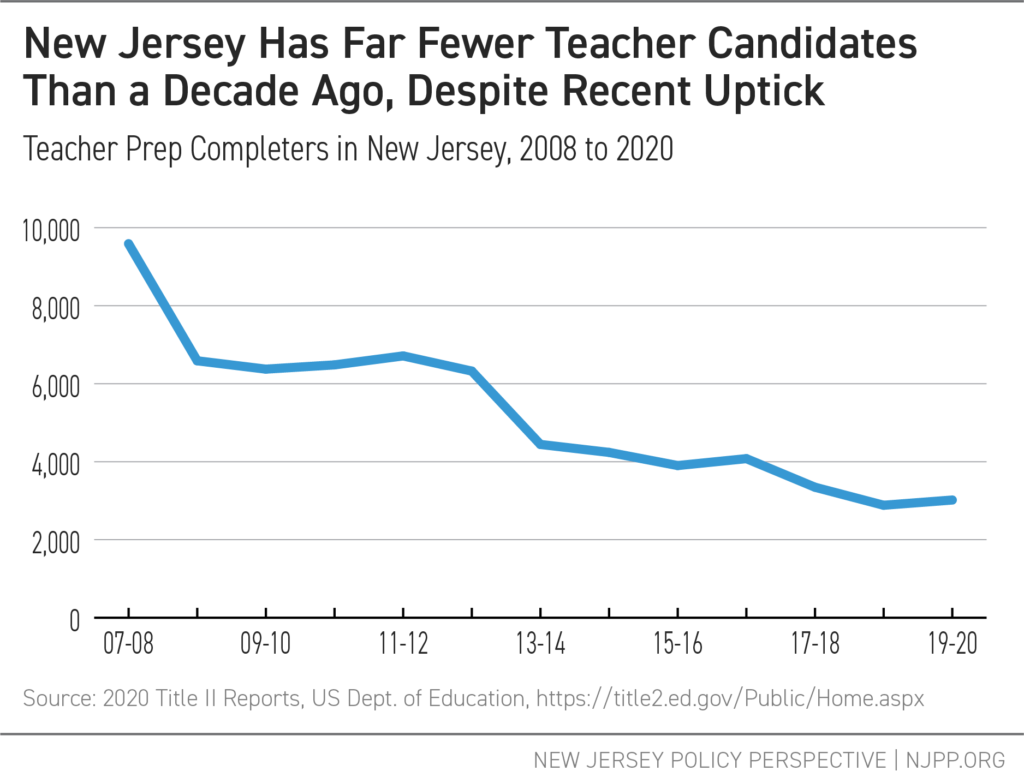

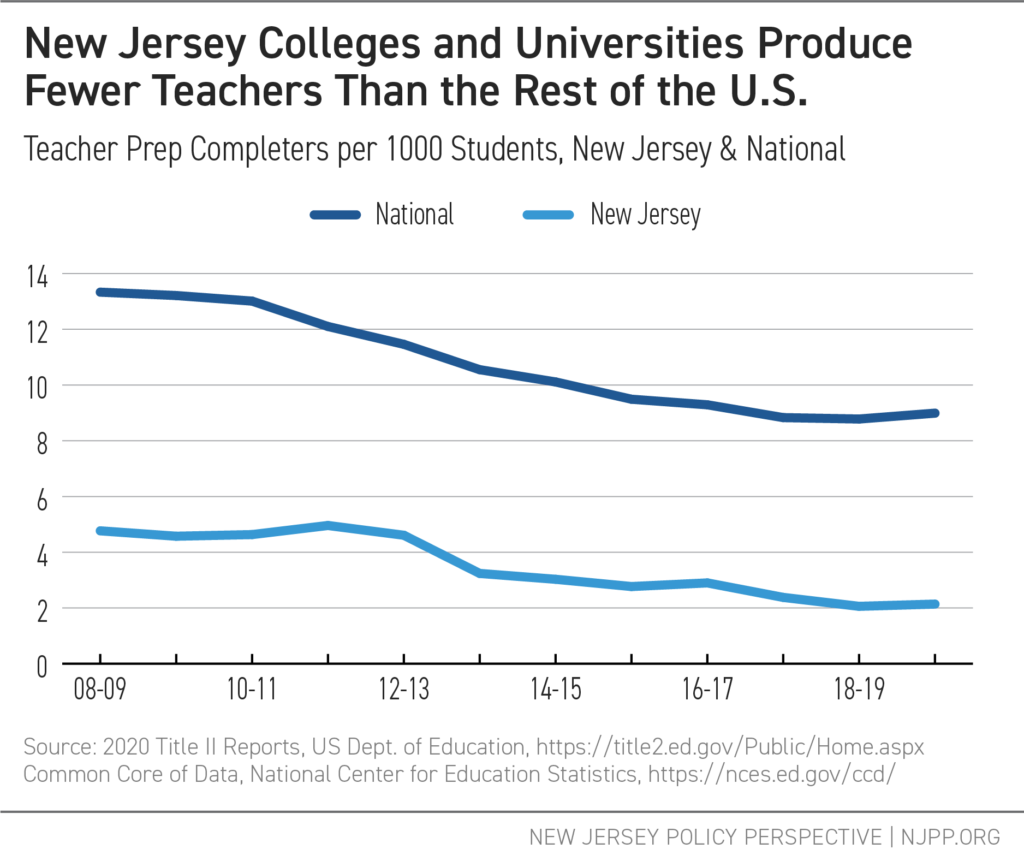

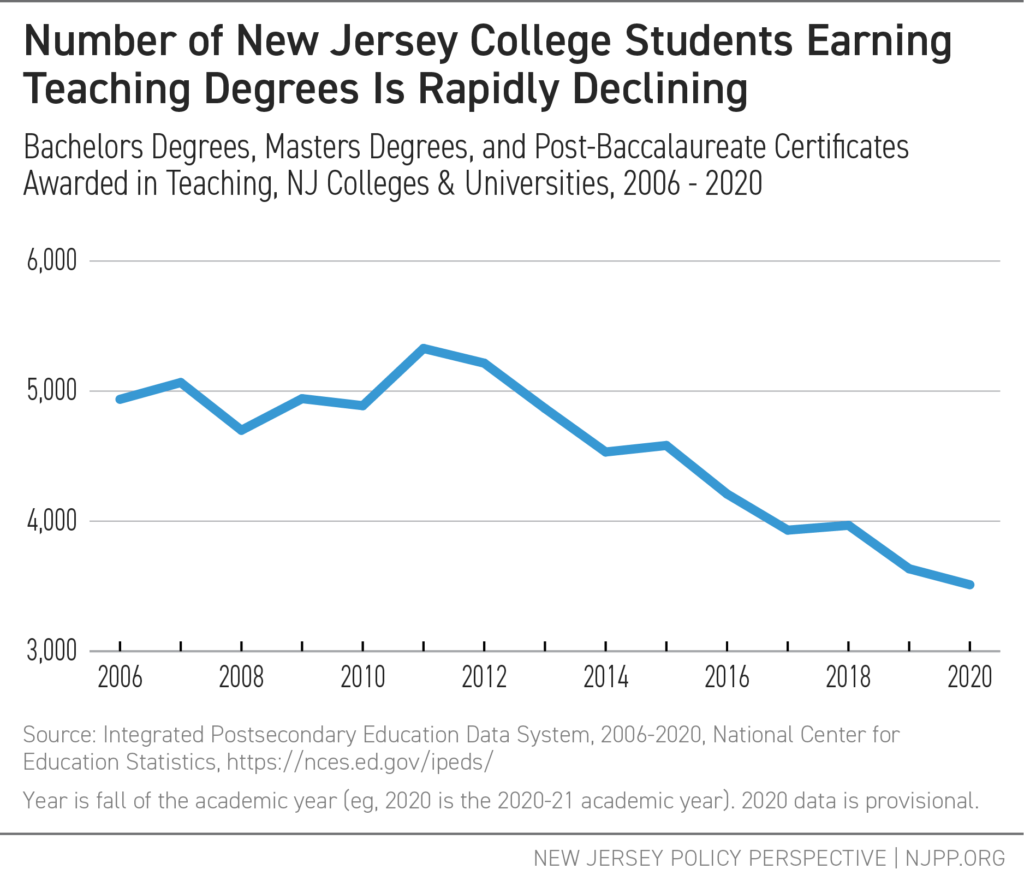

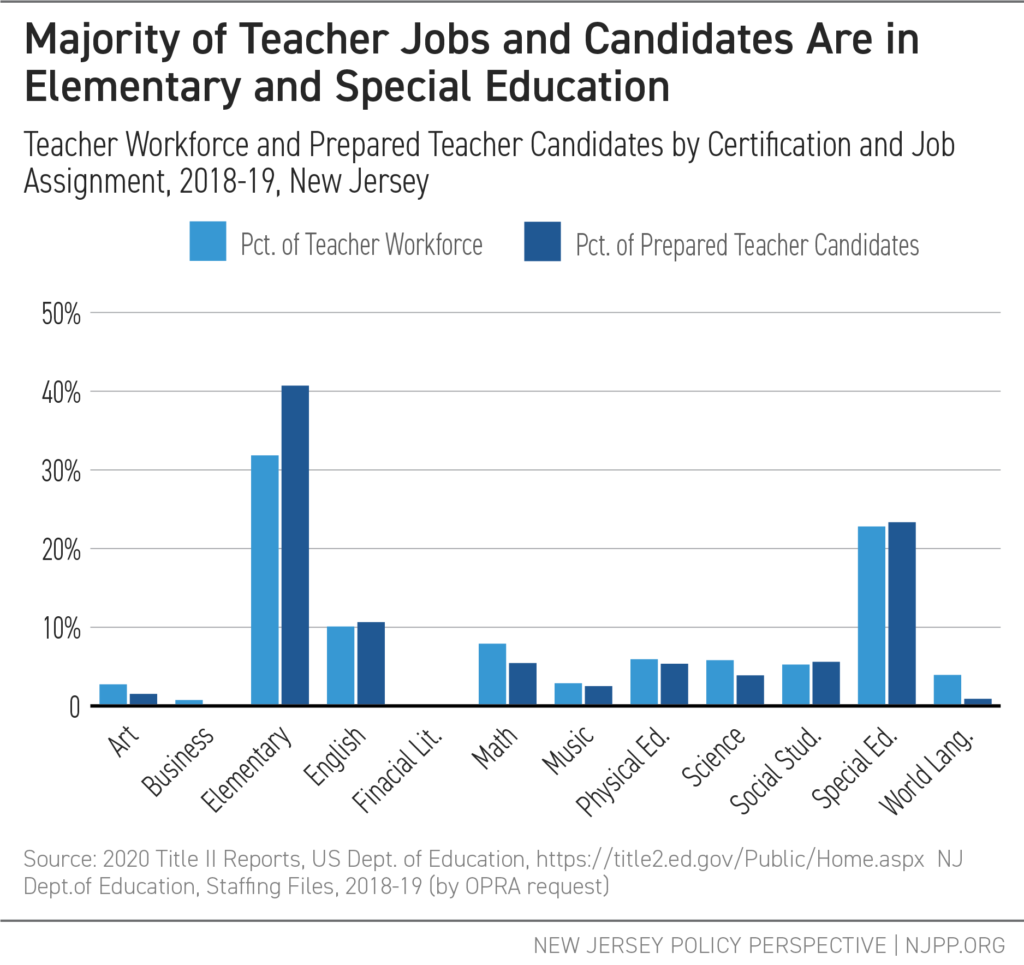

Like many other states, New Jersey is facing a teacher shortage.[1] As the New Jersey Policy Perspective (NJPP) has reported, the state now enrolls significantly fewer teacher candidates in preparation programs than it did a decade ago, signaling an alarming trend in the educator pipeline.[2] Compensation remains a major obstacle to attracting and retaining teachers, with research consistently showing that lower pay and weaker benefits reduce recruitment and retention.[3]

Teacher Retirement Plan Types· Defined Benefit: Employees contribute a percentage of their income throughout their careers and receive a guaranteed benefit upon retirement. Defined benefit plans are what are typically thought of as “pensions.” · Defined Contribution: Both employees and employers contribute to the plan, but the retirement benefit is not predetermined. Instead, the final amount depends on contributions and investment performance. These plans function similarly to 401(k)s in the private sector. · Hybrid: Plans that combine elements of both defined benefit and defined contribution plans. Hybrid plans often have a defined benefit component that requires relatively smaller contributions than full defined benefit plans, but also have a smaller benefit factor. |

Strong retirement benefits can help offset lower salaries by increasing overall compensation; however, New Jersey’s pension system has moved in the opposite direction. Over the last decade, teachers have paid more into their pensions while receiving less in return.

Chapter 78, passed in 2011, not only increased employee contribution rates to record highs but also created a new pension tier, “Tier 5,” for teachers hired after June 2011. [4] Compared to earlier tiers, Tier 5 raised the normal retirement age and lowered the benefit factor — the amount a pension grows with each year of service as a percentage of a teacher’s final salary. As a result, Chapter 78 hits new teachers the hardest, just as the state needs more qualified workers to consider entering and staying in the profession.

In 2017, NJPP published a report quantifying the damage caused by Chapter 78, finding that New Jersey’s pensions were already among the least generous in the country. [5] This updated analysis, using refined methods and the most recent data, finds that little has changed. Without action to address the state’s inadequate retirement benefits for new teachers, New Jersey will continue to struggle to attract and retain the high-quality educators its students deserve.

Ranking Pension Generosity

Retirement programs for teachers vary widely between states, making direct comparisons complex. However, there are various factors many plans have in common. This report compares these factors and ranks their relative value for plan members. It then weighs each factor and averages a state’s rank to arrive at a final grade. Further details can be found in the Appendix.

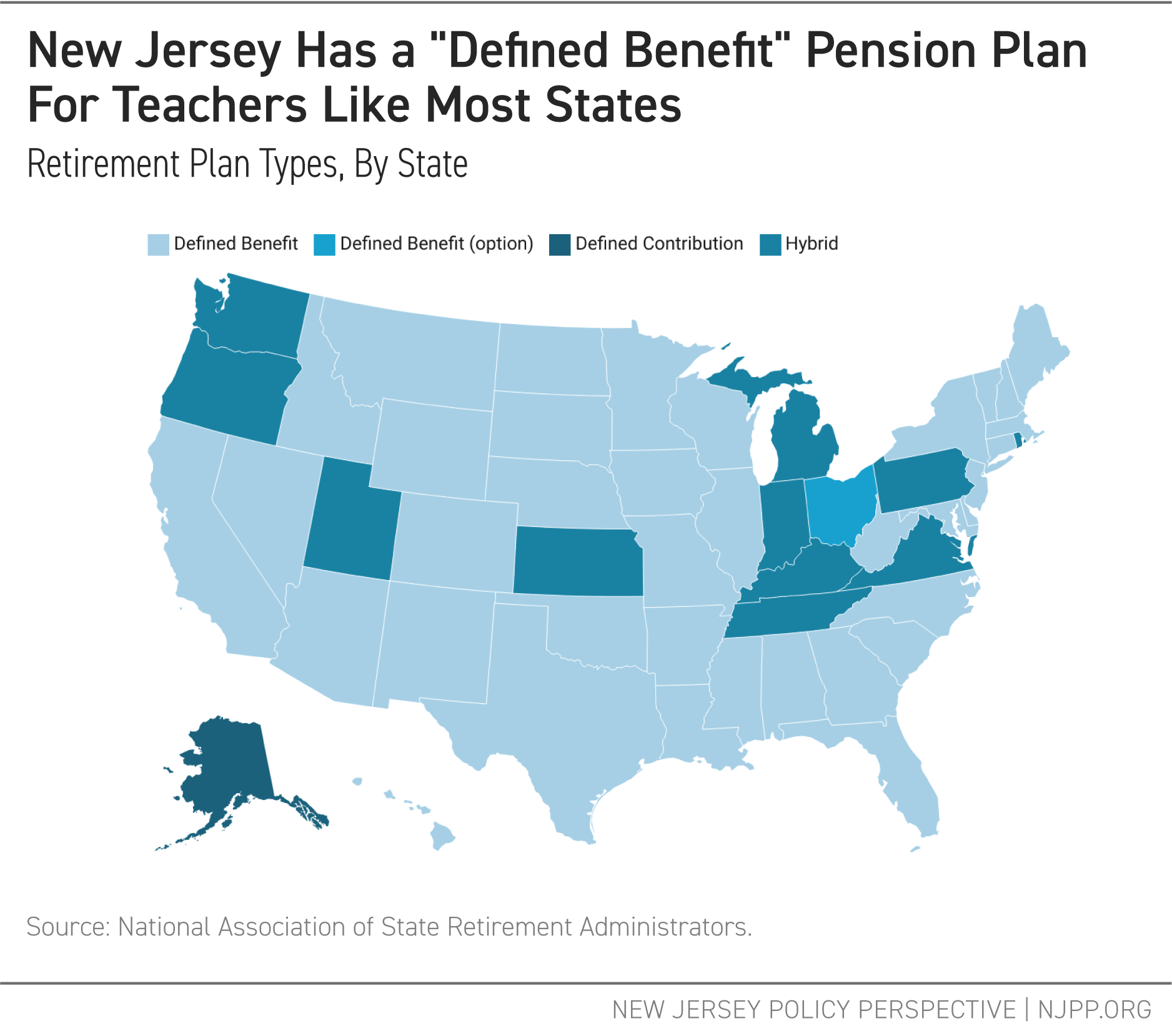

There are three main types of teacher pensions: defined benefit, defined contribution, and hybrid (see box above). Figure 1 shows that most teacher retirement plans for recent members are defined benefit plans, although several states have moved to hybrid plans. Since defined contribution plans introduce market variables that complicate direct comparisons, this analysis focuses exclusively on the 38 states with defined benefit plans, including New Jersey.

Defined benefit plans have six major factors in common that affect their generosity:

- Benefit Factor: The percentage of a salary accrued annually toward the pension and the key factor of a pension’s payout (see below).

- Contribution Rate: The percentage of a salary that must be contributed.

- Average Salary Determination: The salary used to calculate benefits.

- Vesting Period: The number of years required before pension benefits are guaranteed.

- Normal Retirement Age: The earliest age at which a teacher can receive benefits without penalty.

- Cost of Living Allowance (COLA): The increases to the benefit to account for inflation.

Since the benefit factor and contribution rate directly affect a teacher’s benefits, they are weighted twice as heavily as the other four factors when determining a final grade.

Findings

Benefit Factor

Pension benefits follow a basic formula to determine a benefit:

Benefit Factor x Years Employed x Average Salary Determination = Benefit[6]

The benefit factor — sometimes called the retirement multiplier — is the percentage of an employee’s average salary they receive as a pension benefit for every year employed. For example, a teacher who works for 30 years and has a final average salary of $100,000 would receive a pension plan of $30,000 with a benefit factor of 1.0:

1.0 (benefit factor, divided by 100) x 30 (years) x $100,000 (salary) = $30,000

With a benefit factor of 2.0, their pension benefit would double:

2.0 (benefit factor, divided by 100) x 30 (years) x $100,000 (salary) = $60,000

A higher benefit factor means a larger pension benefit. Relative to other states, New Jersey’s benefit factor for new teachers is quite small — ranking sixth lowest among the 38 states with a 1.67 benefit factor.[7]

Contribution Rate

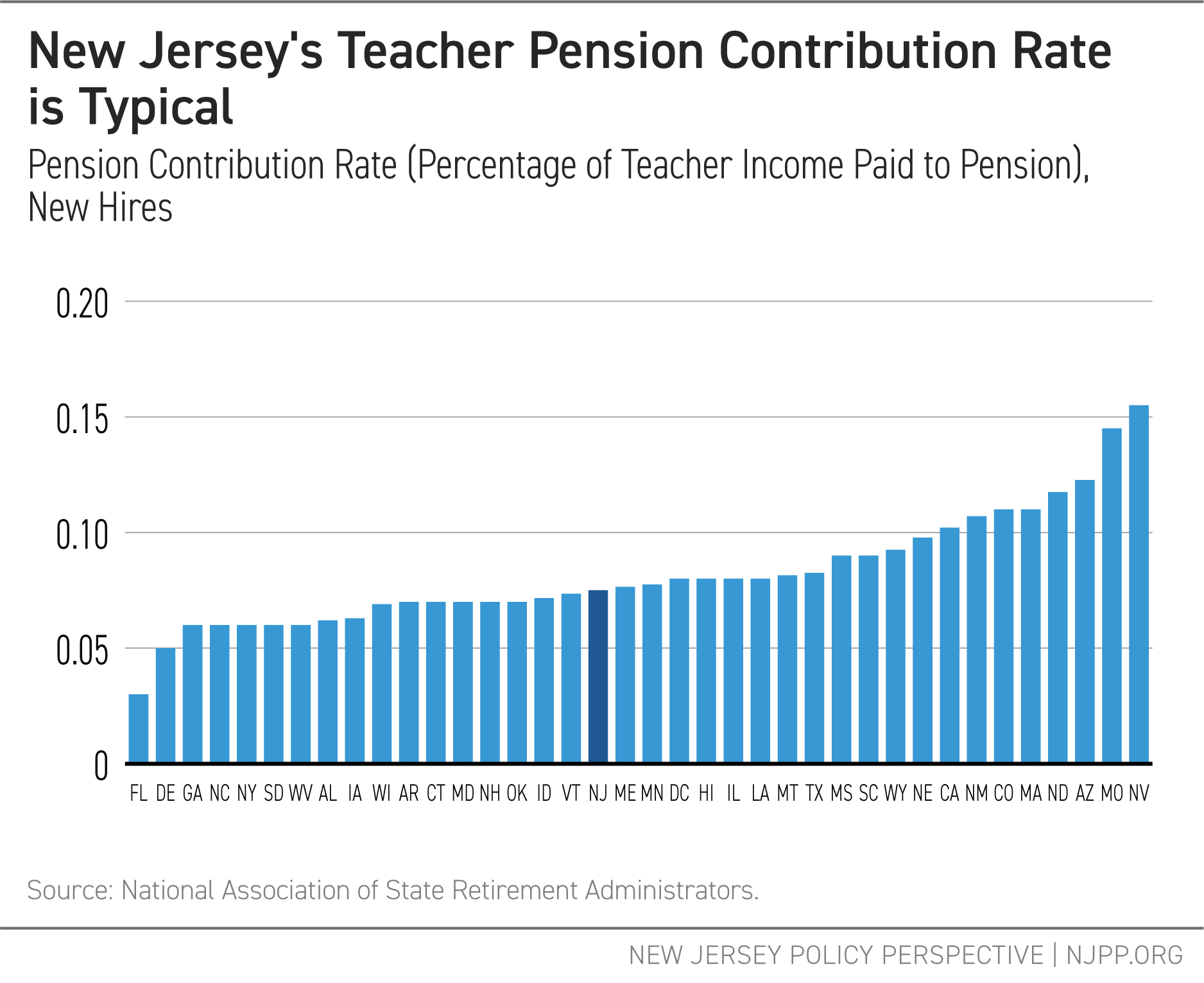

Teachers’ pensions have two funding sources: employer contributions from state or local revenues and employee contributions from teachers’ paychecks. Higher contribution rates mean that teachers pay more for their pensions. At 7.5 percent, New Jersey’s contribution rate ranks in the middle at 18th out of 38.

Average Salary Determination

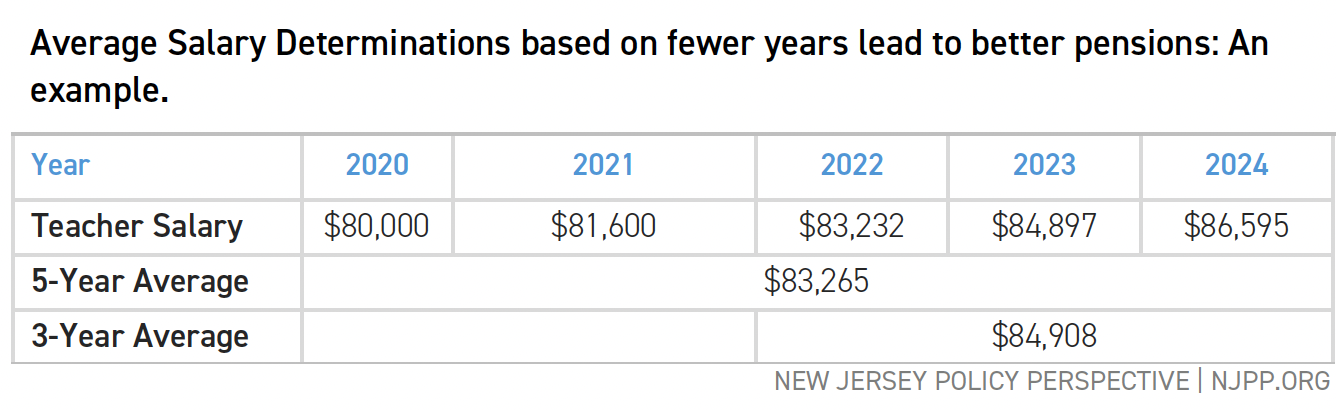

Pension benefits are calculated as a percentage of a teacher’s average salary. The average is based on some number of years when the teacher’s salary was highest. Because most teachers earn more at the end of their careers, and because their salary goes up each year, an average salary determination based on fewer years leads to a higher benefit than a salary based on more years.

As an example: A teacher in 2020 makes $80,000, and her salary increases by 2 percent each year. The average of her last five years is $83,265; however, the average of her last three years is $84,908. A pension based on a three-year average is, therefore, larger than a pension based on a five-year average. In other words, more generous pensions have average salary determinations based on smaller numbers of years.

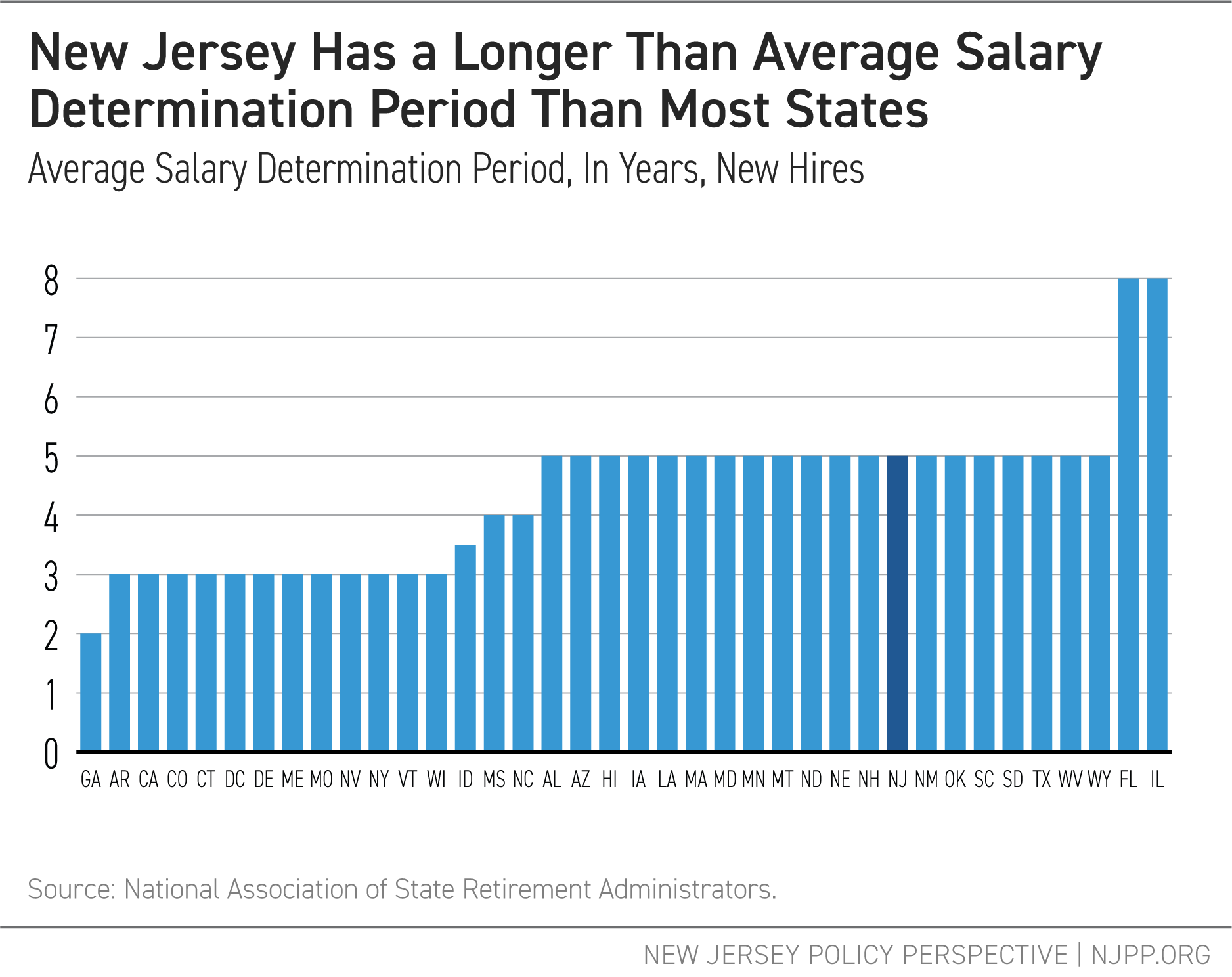

Currently, New Jersey uses five years to determine the average salary, which puts our state tied with 20 other states in terms of average salary determination. Fifteen states use a lower number of years, and two use a higher number of years.

Vesting Period

The vesting period is the length of time a member must work before being guaranteed a pension benefit. New Jersey, like eight other states, requires ten years of service to become vested.

Normal Retirement Age

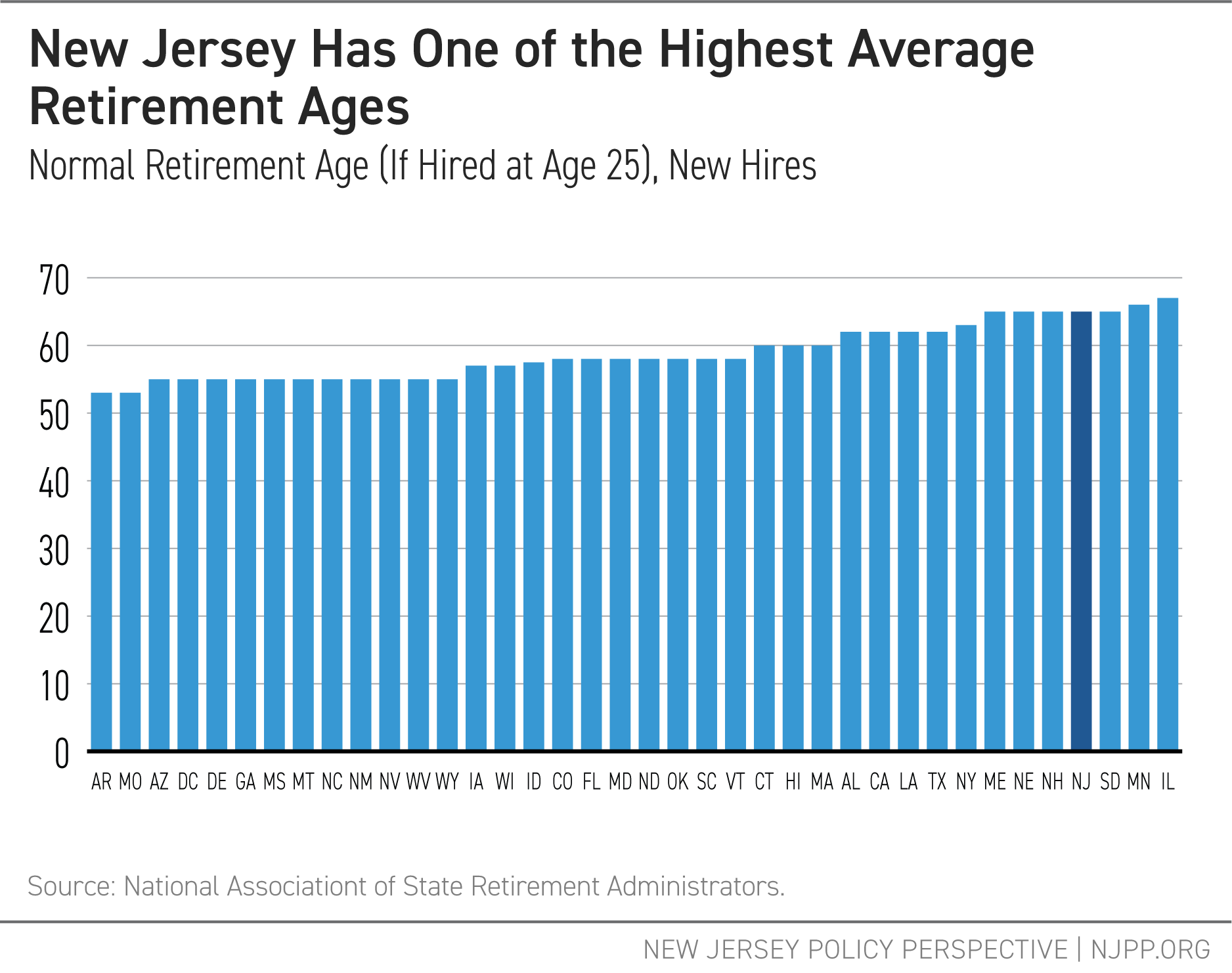

While pension systems can offer options for early retirement, there is usually a penalty for doing so. Normal retirement age is when a member can receive their full pension benefit. While some states have simple age and work years requirements, others use more complex formulas that change the normal retirement age based on when a member started work. For simplicity’s sake, this report gives the normal retirement age for each state, assuming that a teacher entered the state’s retirement plan at age 25.

In this report’s sample of 38 states, the normal retirement age for new teachers ranges from 53 to 67. At 65, novice teachers in New Jersey have one of the highest normal retirement ages in the country.

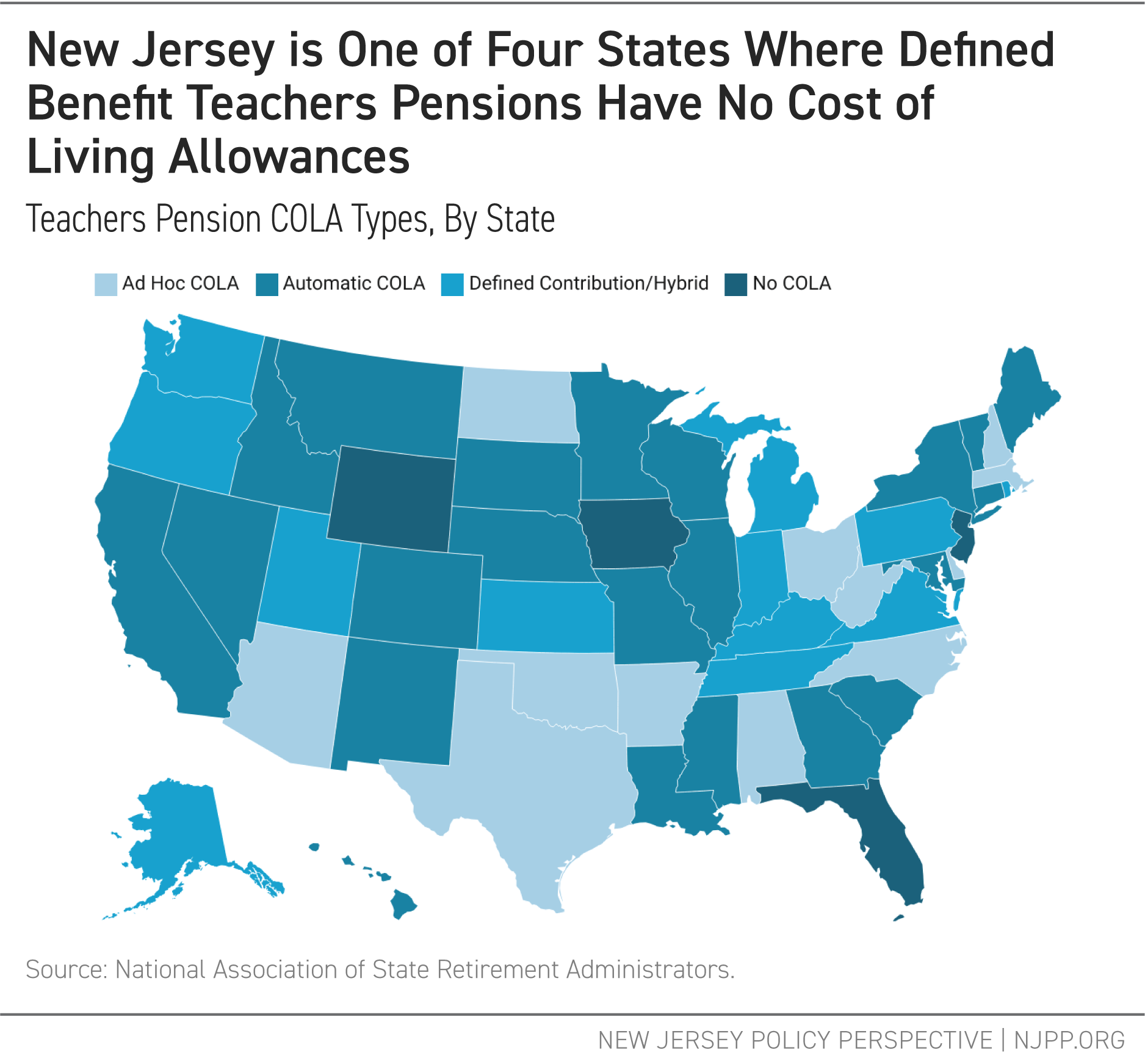

Cost of Living Allowance

Most states offer some increase in benefits for retirees to offset the effects of inflation. The terms of these cost-of-living allowances (COLAs) vary widely. To simplify things, this report examined two factors: 1) whether or not there is a COLA and 2) whether the COLA is automatic or “ad hoc,” meaning it is only granted when some governing body allows it. New Jersey is only one of four states that has no COLA.

Overall Grade

Compared to states with similar retirement plans, New Jersey has the least generous pensions for new teachers in the nation, earning an overall grade of “F.” The state’s low benefit factor, lengthy vesting period, high normal retirement age, lack of a COLA, and high average salary determination period all combine to make New Jersey’s pension for new teachers the stingiest in the nation. See Appendix for more information on the methodology for scoring and letter grades.

In some states, Social Security benefits are not available to teachers; in these cases, teachers do not pay FICA taxes, which is a U.S. federal payroll tax. While the overall grade in this report is not affected by a state’s Social Security status, the information is included in the Appendix. Even if all states that did not participate in Social Security for teachers were excluded from this analysis, New Jersey would still rank last in pension generosity. The role of Social Security in teacher retirement is discussed further in the Supplement.

Recommendations and Conclusion

In 2016, then-Governor Chris Christie claimed that New Jersey teachers had “gold-plated pensions.”[8] However, as NJPP pointed out in 2017,[9] that was simply not true when compared to other states. Teachers’ pensions in New Jersey were some of the least generous in the nation.

Today, new teachers in New Jersey’s pension system continue to face significant disadvantages. They suffer from a low benefit factor, a mediocre contribution rate, a high salary determination and retirement age, and no COLA. By any standard, New Jersey’s newest teachers get a worse deal on their retirement benefits than their colleagues in other states. This inequity is particularly concerning considering that three-quarters of teachers in the state are women — further exacerbating the gender pay gap.[10] A fair pension system is not just about financial security in retirement; it is about recognizing and respecting educators for their service.

To fix this, policymakers must act now to restore fairness in New Jersey’s teacher pension system. The most effective solution is to eliminate Tier 5 and extend more equitable benefits to all teachers. This change would bring New Jersey’s pension system closer to national standards, making the profession more attractive to new educators while ensuring that long-serving teachers can retire with dignity. However, simply eliminating Tier 5 and transitioning all teachers to Tier 1 would not fully align New Jersey with more generous pension systems in other states. While it would mark significant progress, many states would still provide more generous benefits than New Jersey. (See supplement for methodology.)

Governor Murphy’s administration has helped New Jersey make great strides toward meeting its long overdue pension obligations.[11] But if the state wants to recruit and retain well-educated workers into its schools, it must stop using the excuse of previous underfunding to justify inadequate teacher pension benefits. Eliminating Tier 5 is a reasonable step toward pension fairness for the people who educate our children and shape New Jersey’s future.

Appendix: Data and Methods

Data

Data for this report come from the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), the foremost authority on public pensions. Data were extracted from these documents:

- Retirement System Benefits & Eligibility Requirements for General Employees & Teachers (May, 2022) https://www.nasra.org/files/Compiled%20Resources/benefitsandeligibility.pdf

- NASRA Issue Brief: Cost-of-Living Adjustment (May, 2024) https://www.nasra.org/files/Issue%20Briefs/NASRACOLA%20Brief.pdf

- NASRA Issue Brief: Employee Contributions to Public Pension Plans (November, 2024) https://www.nasra.org/files/issue%20briefs/nasracontribbrief.pdf

- Overview of Primary Retirement Benefit Plan Type, by State (July, 2021) https://www.nasra.org//Files/Topical%20Reports/Plan%20Design/Overview%20of%20Primary%20Retirement%20Benefit%20Plan%20Type.pdf

As a data check, NASRA’s data was compared to a report recently issued by the Wisconsin Legislative Council in 2024.[12] When the two data sources conflicted, the author went to the state in question’s website and used the information provided.

Methodology

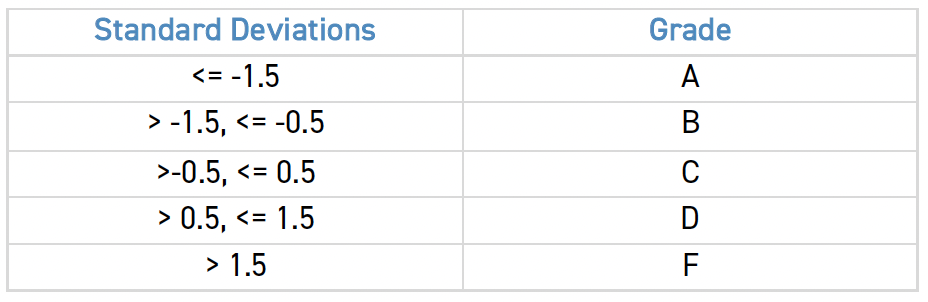

The sample used is restricted to states with defined benefit retirement plans for teachers. States were ranked in all six metrics (ties were ranked at the mean of the states’ ranks). The final score is the average (mean) of the ranks, with the benefit factor and contribution rate ranks weighted twice as much as the others.

For the letter grades, the author converted the rank means into standard deviations and assigned grades based on this distribution.

Supplement: Modeling Pension Generosity

While retirement age, COLAs, vesting periods, and average salary determination are important measures of a pension’s generosity, arguably the two most important factors are the benefit factor and the contribution rate. The first directly affects the value of the pension benefit, and the second determines how much an employee pays to get that benefit.

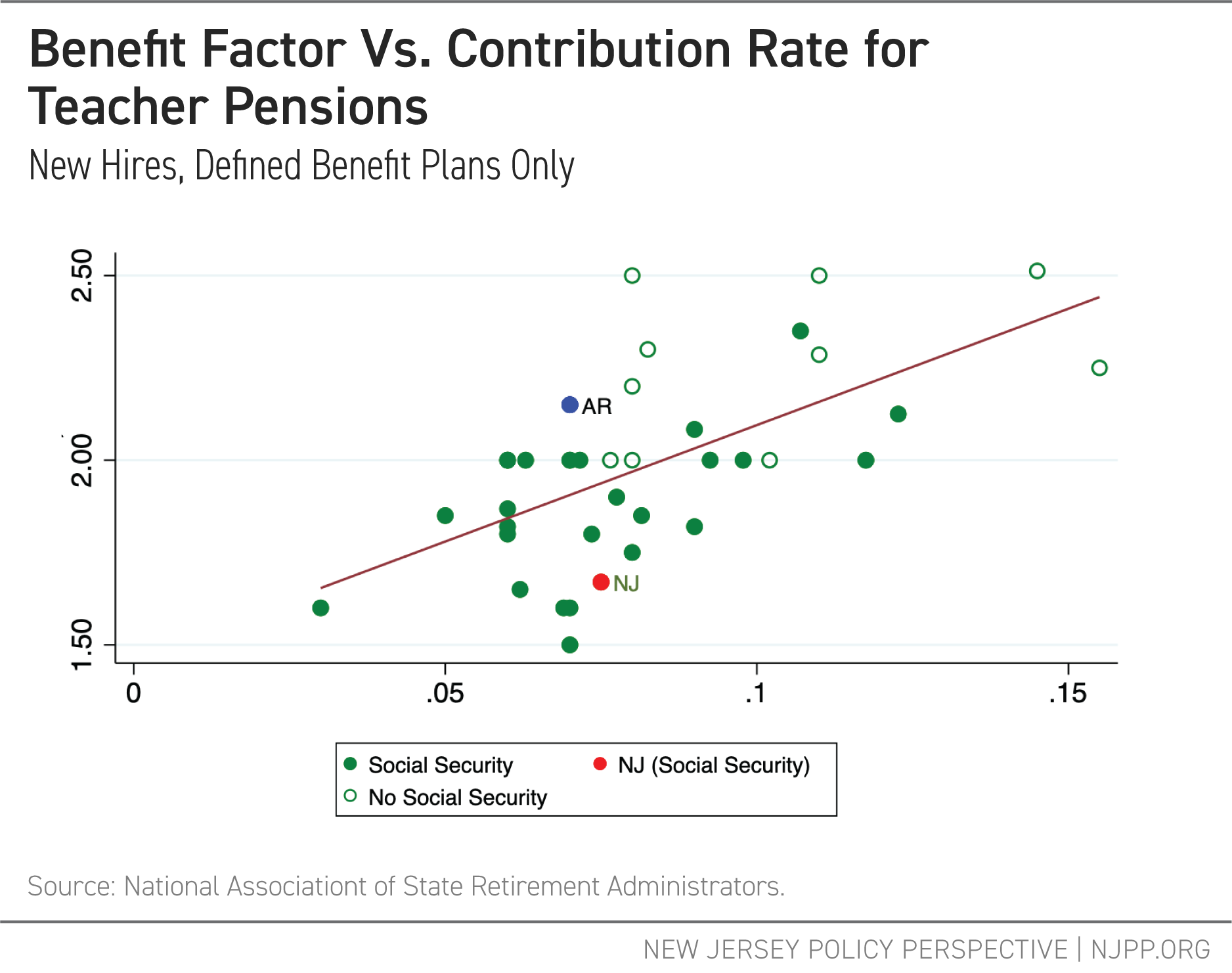

Logically, members would expect that the more they pay into a pension, the more they would get out of it. In other words, states with higher contribution rates should have, on average, higher benefit factors. The figure below shows a significant correlation (r-sq = 0.38) between the benefit factor and contribution rate.

But the correlation is hardly perfect. Some states have higher benefit factors than their contribution rates would predict, and some have lower. New Jersey, for example, has a slightly higher contribution rate (7.5%) than Arkansas (7.0%). However, Arkansas’s benefit factor (2.15) is much higher than New Jersey’s (1.67). Arkansas teachers enjoy a more generous pension multiplier than New Jersey teachers, even though they contribute a smaller portion of their income.

The amount that the benefit factor is above or below what the contribution rate predicts is the “value-added” of that state’s pension: the amount more or less than predicted, based on other states’ pensions, that a member receives in benefits based on what they contributed. Teachers in states with a higher value-added amount enjoy more generous pensions as evaluated by these two critical factors; teachers in lower value-added states have less generous pensions.

The figure above also shows that states that do not offer Social Security benefits for their teachers (the green markers) tend to have higher value-added amounts. They sit higher above the trendline, which is the model’s prediction of the benefit factor given the contribution rate. To put it more simply, states do not have to pay the employer’s share of Social Security taxes on behalf of their teachers and may use those funds to increase the benefit factor.

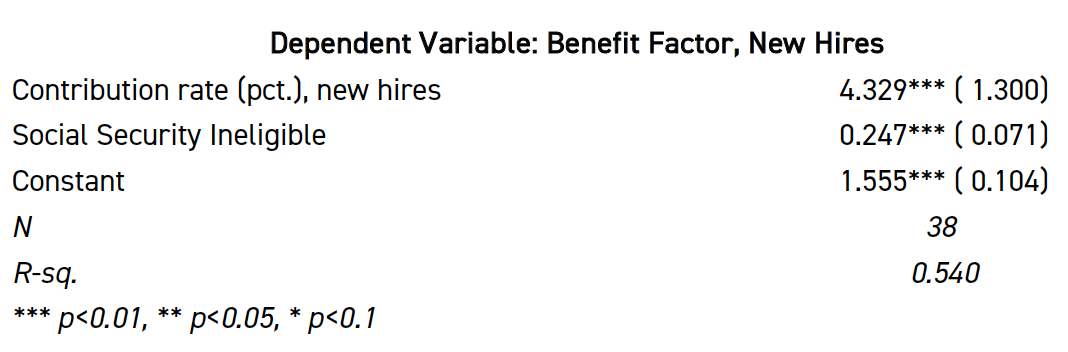

To account for this, the author runs a regression model with Social Security as a factor variable. The estimates are below; the model allows us to calculate the predicted benefit factor for each state and compare it to the actual benefit factor (resulting in the residual).

Using this model, New Jersey’s predicted benefit factor is 1.88. Its actual benefit factor for Tier 5, as discussed above, is 1.67, and its benefit factor for Tier 1 is 1.82. While the Tier 1 benefit factor is still below the prediction, it is much closer than Tier 5. Raising the Tier 5 benefit factor to Tier 1’s would go a long way toward making New Jersey’s pension benefits for new teachers more like those in other states.

Disclosure

Mark Weber is the Special Analyst for Education Policy at the New Jersey Policy Perspective, and a Lecturer in education policy and law at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. Weber is also a teacher in the Warren Township Schools, Somerset Country; as such, he is a member of the New Jersey Teachers’ Pension and Annuity Fund (TPAF). Weber is in Tier 1; the recommendations in this report would not affect his retirement benefits.

End Notes

[1] Nikita Biryukov (September 3, 2024). “New Jersey districts still face teacher shortages as new school year begins.” New Jersey Monitor. https://newjerseymonitor.com/2024/09/03/new-jersey-districts-still-face-teacher-shortages-as-new-school-year-begins/

[2] Weber, M. (2022). New Jersey’s Teacher Pipeline: The Decline in Teacher Candidates Continues. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/new-jerseys-teacher-pipeline-the-decline-in-teacher-candidates-continues/

[3] Allegretto, S. (September 12, 2024). Teacher pay rises in 2023—but not enough to shrink pay gap with other college graduates. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/teacher-pay-in-2023/

Weber, M. (September, 2019). In Brief: New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019; Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists. New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NJPP-In-Brief-Teacher-Workforce-Report-Final.pdf

Kemper Patrick, S. & Carver-Thomas, D. (2022). Teacher Salaries: A Key Factor in Recruitment and Retention. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/teacher-salaries-key-factor-recruitment-and-retention

Steiner, E., Woo, A., Doan, S. (November 20, 2024). Larger Pay Increases and Adequate Benefits Could Improve Teacher Retention. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-13.html

[4] New Jersey Treasury. “Pension and Health Benefits Reform Under Chapter 78, P.L. 2011.” https://www.nj.gov/treasury/pensions/reform-2011.shtml

[5] Herzenberg, S. and White, J. (December 13, 2017). New Jersey Public Pensions Rank Among Least Generous in the Nation. New Jersey Policy Perspective. http://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NJ-Pension-Brief-12-13-17-Final.pdf

[6] National Association of State Retirement Administrators. “Defined Benefit.” https://www.nasra.org/db

[7] In some states, benefit factors are based on variables such as years of service and age of retirement. To standardize these figures for comparison, we use the benefit factor for a teacher who begins work at age 25 and retires at the state’s “normal” retirement age. We also elect not to use the NASRA’s reported benefit factor for Massachusetts, which does not align with figures reported by the state; instead, we assume a retirement at 60 and a start age of 25 (see: https://mtrs.state.ma.us/members/#retiring-from-mtrs). We also use the “RetirementPlus” formula, as new members are automatically enrolled (see: https://mtrs.state.ma.us/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/retirementpercentagechart-tier2.pdf)

[8] Star-Ledger Editorial Board (January 17, 2016). “Stop demonizing teachers, governor; Editorial.” The Star-Ledger. https://www.nj.com/opinion/2016/01/christie_has_no_right_to_demonize_teachers_editori.html

[9] Herzenberg, S. and White, J. (December 13, 2017). New Jersey Public Pensions Rank Among Least Generous in the Nation. New Jersey Policy Perspective. http://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NJ-Pension-Brief-12-13-17-Final.pdf

[10] Gould, E. (March 8, 2024) Gender wage gap persists in 2023; Women are paid roughly 22% less than men on average. Economic Policy Institute.https://www.epi.org/blog/gender-wage-gap-persists-in-2023-women-are-paid-roughly-22-less-than-men-on-average/

[11] New Jersey Treasury (October 31, 2024). “New Jersey’s Pension Fund Reports 10.74% Returns for FY2024.” https://www.nj.gov/treasury/news/2024/10312024.shtml

[12] Wisconsin Legislative Council. 2023-24 Comparative Study Of Major Public Employee Retirement Systems, October 2024. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/misc/lc/comparative_retirement_study/2023_retirement.pdf

Local Fair Share

Local Fair Share