To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

On any given day and in every corner of the state, immigrants – both documented and undocumented – wake up and set out to work at small, local businesses that they themselves own and operate. This follows a nationwide trend, as immigrants are almost twice as likely to start new businesses than their native-born peers. And while immigrants are more likely to open any kind of business — including large corporations like Tesla, Google, and Pfizer — they are much more likely to own a “Main Street” business than native-born residents.[1] These small businesses, like grocery stores, hair salons and restaurants, generate approximately $1 billion in economic activity every year and are critical to downtowns and local economies across New Jersey with its 565 unique municipalities.

Immigrants own a higher share of Main Street businesses in New Jersey than in any other state not named California.[2] In fact, immigrants account for 47 percent of the Garden State’s Main Street business owners despite making up just 22 percent of the total population.[3] Given the state’s many small towns and its diversity of immigrants — New Jersey has the third highest share of immigrants and arguably the most ethnically diverse immigrant population and workforce in the nation — this is perhaps not surprising, but it is nonetheless important to the state’s economy.

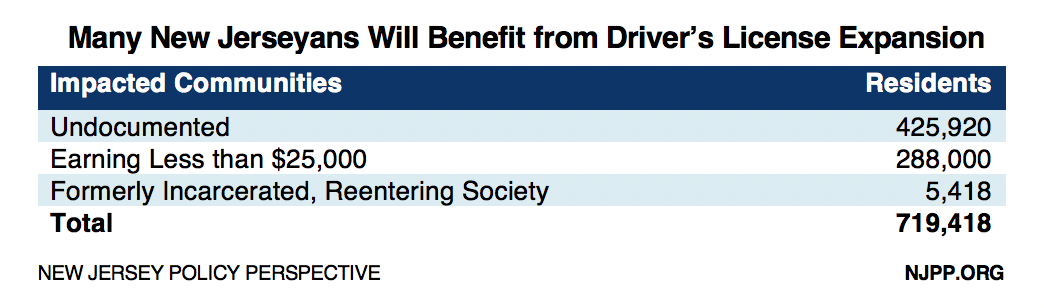

Proactive immigration policies are inextricably linked to the success of immigrant-owned businesses, yet decisions on these issues are often made without input from immigrant business communities. For example, a proposal to expand access to driver’s licenses to all residents, regardless of immigration status, will allow customers of immigrant-owned businesses to have more purchasing power. This policy would also allow employees of immigrant-owned businesses to leave work on their own terms — not just when the last bus or train departs — and become more financially secure and independent.[4]

New Jersey’s Immigrant Entrepreneurs Are Diverse and Own a Variety of Businesses

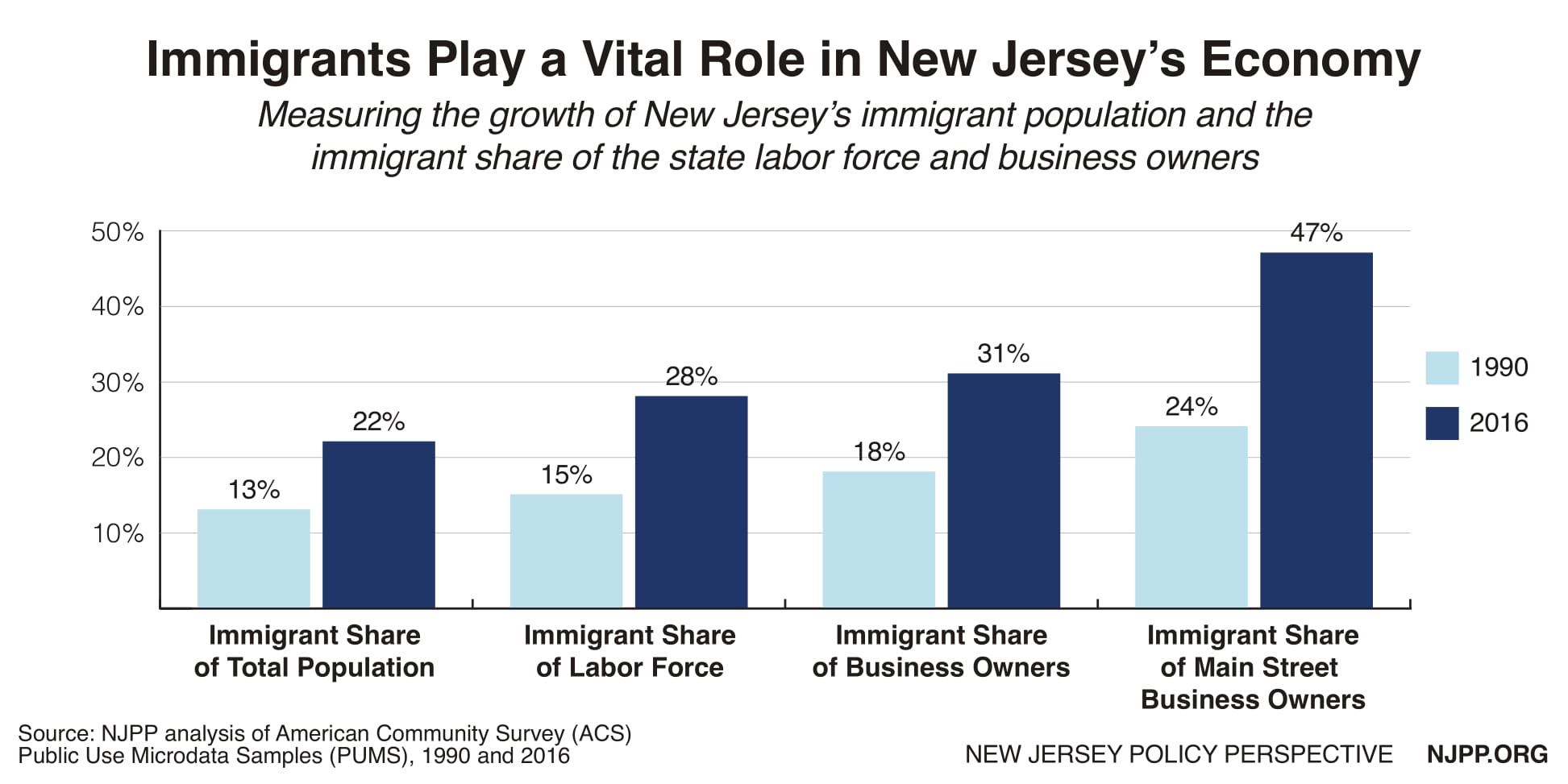

New Jersey’s immigrant population has doubled since 1990, and the shares of immigrants in the labor force and immigrant business owners have grown along with it. In 2016, immigrants made up 31 percent of New Jersey’s business owners and 28 percent of the labor force, up from 18 percent and 15 percent, respectively, in 1990.

The immigrant share of Main Street business owners has also grown tremendously, doubling over the same time — to 47 percent in 2016 from 24 percent in 1990.

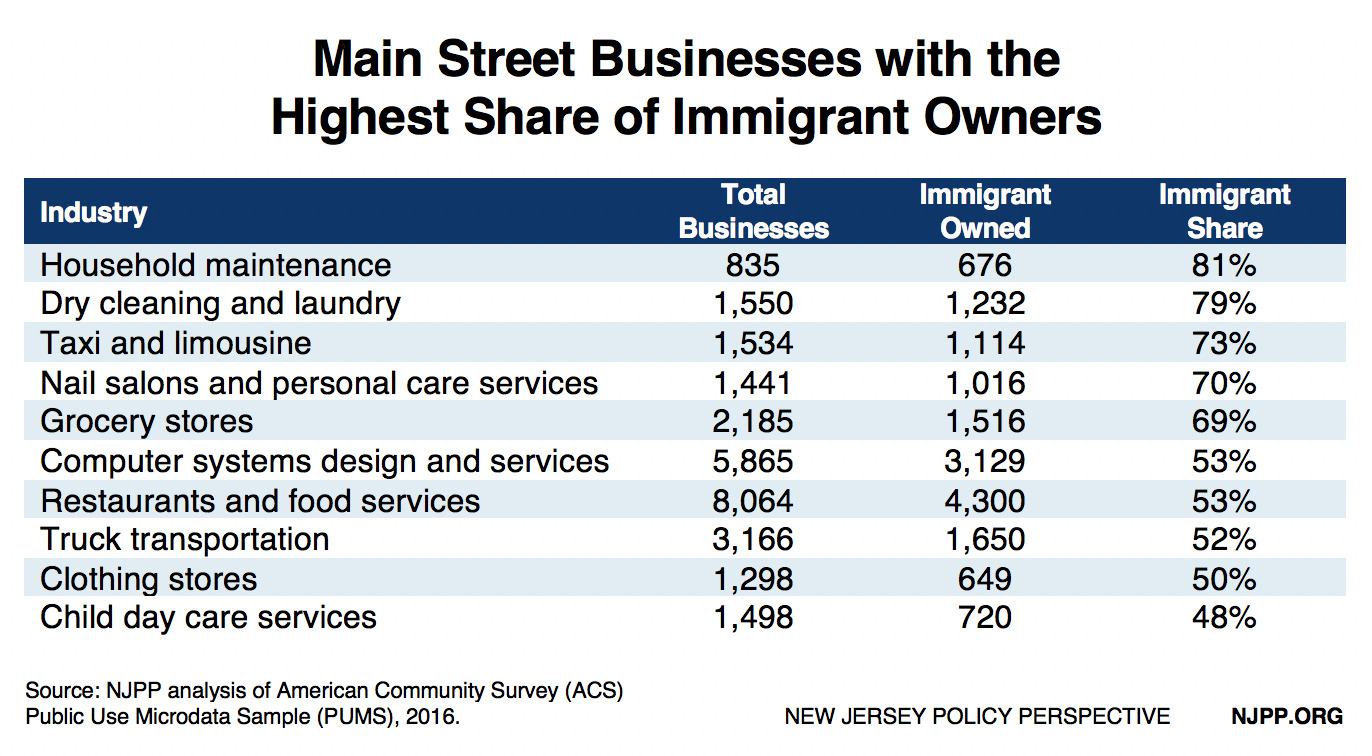

And while a majority (53 percent) of New Jersey’s Main Street businesses are owned by individuals born in the US, 8 out of 10 dry cleaners and 7 out of 10 grocery stores and bodegas are owned by immigrants. Further, immigrant entrepreneurs own 50 percent or more of the state’s household maintenance businesses, transportation services, nail salons, computer service centers, restaurants, and clothing stores.[5]

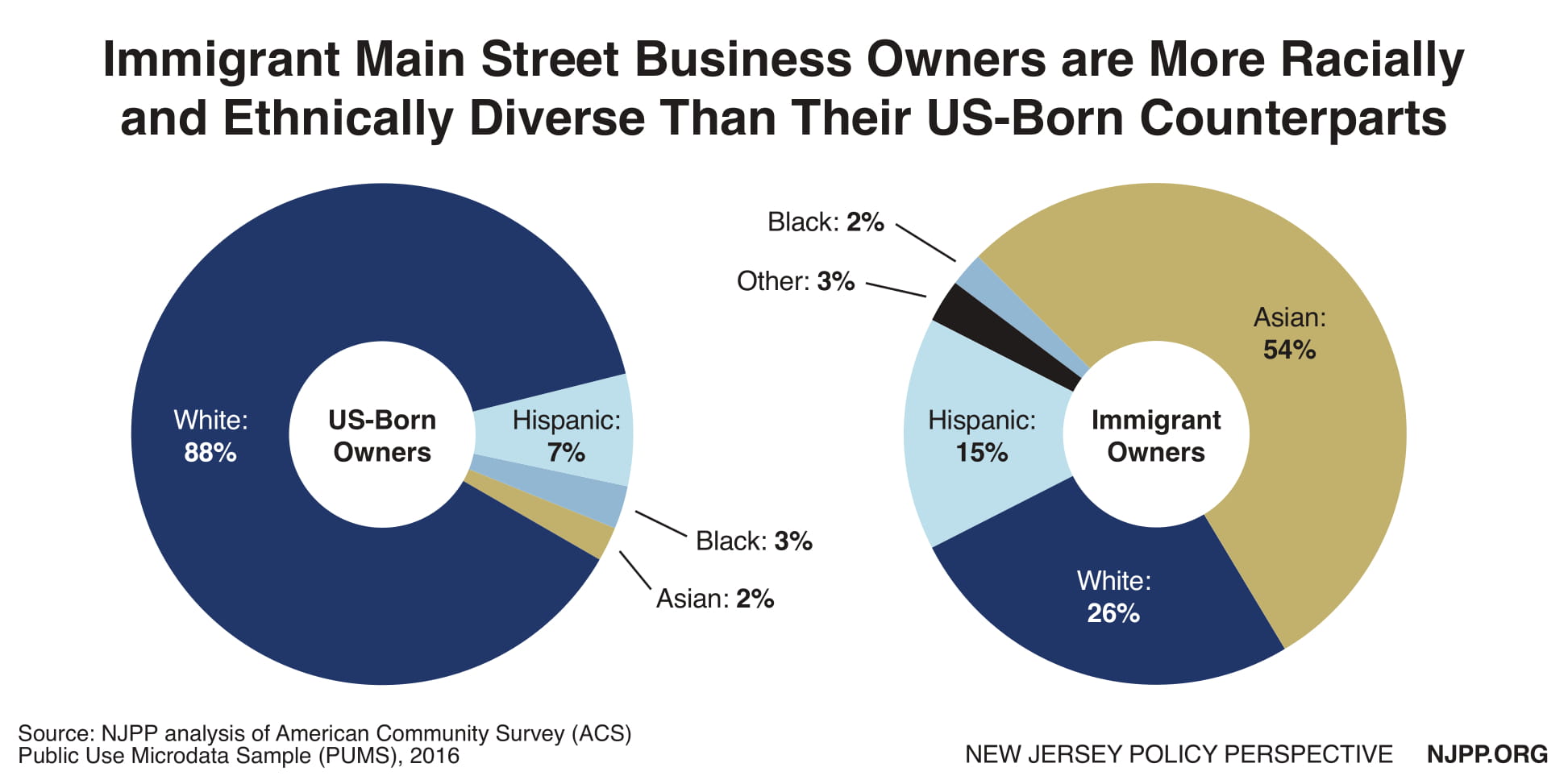

New Jersey’s immigrant entrepreneurs are diverse in the types of businesses they own and in regard to their race and ethnicity. A majority (54 percent) of Main Street immigrant business owners are Asian, while fifteen percent are Hispanic.[6] Asian and Hispanic immigrants are much more likely than their US-born peers to own Main Street businesses. However, Black immigrants only account for two percent of immigrant owned Main Street businesses.

What Makes Immigrants More Likely to be Business Owners

Mounting evidence suggests that immigrants are more likely to start and own small businesses because they face discrimination in the job market due to limited English proficiency and, sometimes, their citizenship status.[7] In addition, immigrants who earned advanced degrees in their home country have trouble continuing their careers in the US as foreign qualifications and academic achievements may not be recognized.

Ray Lamboy, Executive Director of the Latin American Economic Development Association (LAEDA), a nonprofit dedicated to helping immigrants and ethnic minorities start their own businesses, reinforces these findings:

“First generation immigrants do not typically have the access or the time to develop strong networks of support in the business community. This makes it difficult for immigrants to acquire full-time, professional positions in the workforce. Within immigrant communities, connections and networks are more easily established, making it easier for immigrants to find support in starting their own business.

“An example of a strong immigrant entrepreneur network can be found in South Jersey, where a large share of small businesses are owned by immigrants from the Puebla region of Mexico. These immigrants own a majority of the Latino owned businesses in Camden and the Vineland–Millville–Bridgeton metro-region. A majority of these businesses are supported with resources from other immigrant entrepreneurs from the same part of Mexico.”[8]

Immigrant-owned businesses are often a source of first jobs for other immigrants in the community for two reasons: the stepladder experience and block mobility.[9]

The stepladder experience is the idea that immigrant businesses function as a training platform for other immigrants to gain knowledge on how business is done in the United States, obtain work experience, and build social capital.[10] Some immigrants start their business in the informal market (businesses that are not incorporated or legally recognized) and then incorporate it once they gain experience, capital, and knowledge of the market and regulatory landscape. For instance, Felix Sanchez of Passaic, New Jersey started his businesses selling tortillas in the informal market, going door-to-door. As his community’s Latino population grew, so did his business, in spite of him not speaking English and dropping out of school after sixth grade. His company, Puebla Foods, is now a multi-million-dollar business.[11]

Block mobility explains that immigrants seek to be business owners resulting from the disadvantages and discriminations they often suffer in the labor market due to a lack of English proficiency and trouble transferring their foreign-earned degrees.

Economic Impact and Disparities in Earnings Between Native-Born and Immigrant Small Business Owners

Owning a Main Street business comes with increased social capital, as these establishments are an important part of the fabric of their respective local communities. However, owning a Main Street business does not guarantee a higher salary.

The average annual earnings for an immigrant Main Street business owner in New Jersey are $45,117. This is less than the average earnings for their US-born counterparts, who make $53,998 per year. When counting all businesses, the average annual earnings for an immigrant entrepreneur are $55,998. For US-born businesses owners, the average annual earnings are $75,062. For context, the average New Jersey immigrant earns $45,037 per year while US-born New Jerseyans earn an average salary of $58,000.[12]

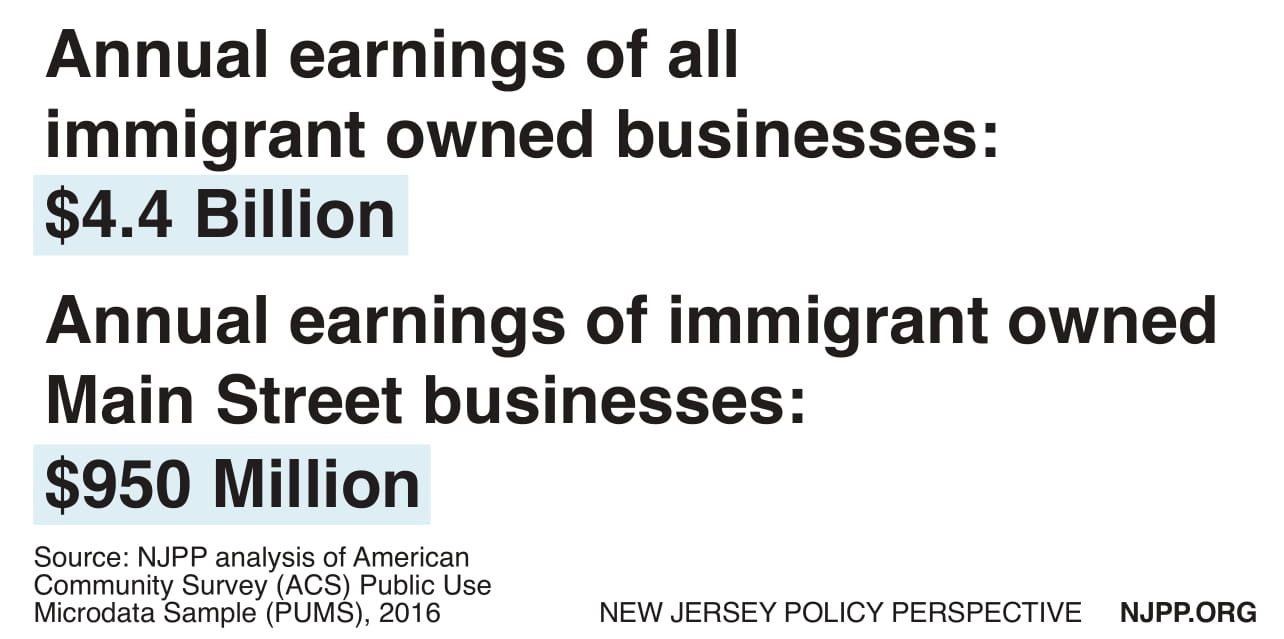

Nevertheless, New Jersey’s immigrant business owners are a critical part of the state’s economy. In total, New Jersey’s immigrant-owned businesses earn $4.4 billion dollars per year, including $950 million per year from Main Street businesses.[13] These earnings inject money into local economies, employ thousands of New Jersey workers, and in some cases, act as a lifeline for neighborhoods that have experienced decades of disinvestment and population decline.

Education and Gender Disparities

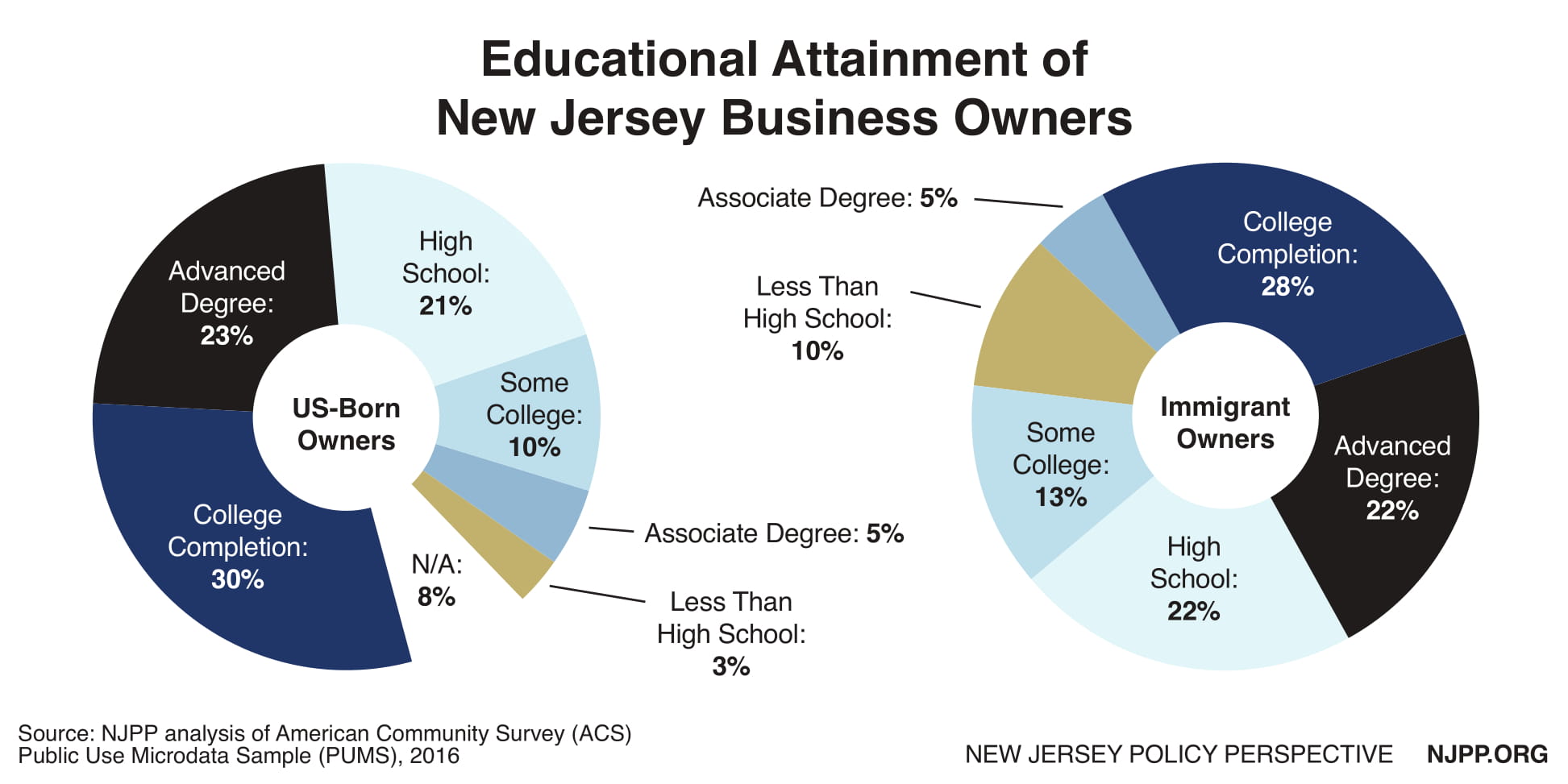

Higher-education is strongly correlated with owning a business. This is true for both immigrants and US-born business owners. Half of immigrant business owners — 50 percent — have either completed college or have an advanced degree. US-born business owners mirror these levels of education, as 53 percent have completed college or have an advanced degree.

Education, however, is not as strong a predictor of immigrant business ownership as it is for US-born entrepreneurs. Almost a third of immigrant business owners — 32 percent — have a high school degree or less. This is eight percentage points higher than US-born business owners, as only 24 percent have a high degree or less. This exemplifies the impact of the stepladder effect, which explains how many immigrants gain the necessary experience within the immigrant business sector to open their own business.

In regard to the gender breakdown of business ownership, men own a greater share of businesses than women. Men own 74 percent of total businesses and 67 percent of Main Street businesses. Immigrant women are slightly more likely to own a business than US-born women.

Immigrant Owned Small Businesses Are a Critical Part of New Jersey’s Economy

Small businesses are the backbone of local economies and communities across the state.[14] Small businesses, specifically those on Main Street, help neighborhoods stay economically active and, in some cases, revitalize cities experiencing population decline. Small businesses also help increase the local tax base and stimulate consumer spending in local economies.[15]

New Jerseyans born outside of the US are an asset not only to the state’s culture but also to its broader economy. Policymakers and the public alike should recognize the contributions of immigrants and the vital role they play on Main Streets in every corner of the state. It is in everyone’s best interest to have proactive policies that allow immigrants to prosper and feel safe and secure here in the Garden State. When immigrants do better, we all do better.

Endnotes

[1] Dyssegaard K.David, Bringing Vitality to Main Street: How Immigrant Small Businesses Help Local Economies Grow. Fiscal Policy Institute. 2015.

[2] Main Street businesses are defined by this report as small businesses focused on neighborhood services, accommodation and food services, and retail. This definition is consistent with that used by David K. Dyssegaard, cited above.

[3] NJPP analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) 2016, Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), 5-Year. Data obtained from Fiscal Policy Institute.

[4] Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Arenas-Arroyo, E., & Sevilla, A. (2018). Labor Market Impacts of States Issuing of Driving Licenses to Undocumented Immigrants (No. 12049). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). http://ftp.iza.org/dp12049.pdf.

[5] Private Households subsector include private households that engage in employing workers on or about the premises in activities primarily concerned with the operation of the household. These private households may employ individuals, such as cooks, maids, butlers, and outside workers, such as gardeners, caretakers, and other maintenance workers. Source: https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag814.html

[6] Ibid 3.

[7] Zhou, M. (2004). Revisiting Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Convergences, Controversies, and Conceptual Advancements. The International Migration Review,38(3), 1040-1074. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27645425

[8] NJPP interview conducted with Ray Lamboy, Executive Director of Latin American Economic Development Association, January 2019. http://www.laeda.com/

[9] Ibid 1.

[10] Ibid 7.

[11] Semple, Kirk. Moving to U.S. and Amassing a Fortune, No English Needed. New York Times. 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/09/nyregion/immigrant-entrepreneurs-succeed-without-english.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0

[12] Ibid 3.

[13] Ibid 3.

[14] Nava, Erika (2017). New Jersey Immigrants are a Huge Economic Driver. https://www.njpp.org/blog/new-jerseys-immigrants-are-a-huge-economic-driver

[15] Ibid 1.