Today, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on the legality of the Trump administration’s attempt to terminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. In place since 2012, DACA protects young people without documents from deportation and allows them to work legally in the United States. These arguments will ultimately inform the Court’s decision by no later than July 2020.

What this means for New Jersey:

In New Jersey, nearly 17,000 DACA recipients could lose their protections against deportation.[i] Being stripped of their work permits, driver’s licenses, and other benefits attached to their protected status would all but eliminate their opportunities to earn a living. If this happens, New Jersey as a whole will feel the negative effects both socially and economically.

DACA recipients are important members of our communities and have been so ever since they arrived in the U.S., with the average age of arrivals being just 8 years old.[ii] They have attended and graduated from our public schools, colleges and universities, work alongside us every day at our jobs, and are neighbors and loved ones who make our communities stronger.

DACA recipients also contribute to the economic fabric of the Garden State. Taken as a group, they pay about $183 million in federal taxes and $100 million in state and local taxes each year – amounts that will significantly shrink if the Supreme Court sides with the Trump administration.[iii] This would result in the loss of important revenue at local, state, and federal levels, reducing critical resources to invest in public assets and programs that we all rely on.

Additionally, DACA recipients contribute $718.9 million to New Jersey’s economy, representing an important degree of spending power.[iv] If DACA is terminated, New Jersey residents would spend less in their local economies, hurting local businesses that help our communities thrive.

Finally, DACA recipients pay $15.7 million in mortgage payments and $79.2 million in rental payments each year.[v] If DACA is terminated, many New Jersey residents would lose their work permits, putting them at risk of losing their jobs and creating a dangerous scenario where they cannot afford to pay basic living costs such as mortgage or rent.

What can New Jersey officials do:

Regardless of whether DACA is rescinded or remains active, New Jersey legislators and the Governor should support and pass proactive immigration policies that will help DACA recipients and their families thrive in New Jersey. Such policies include:

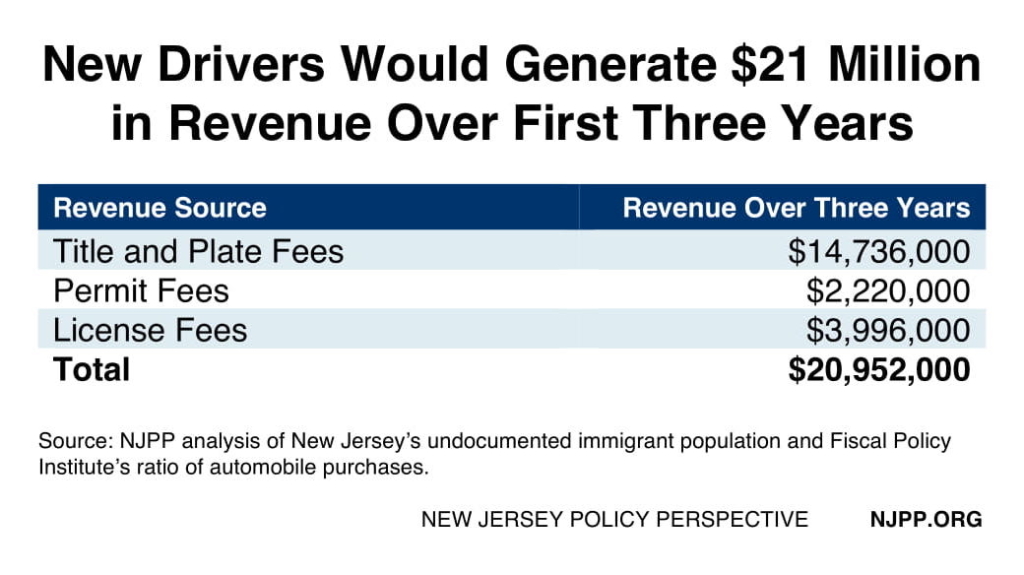

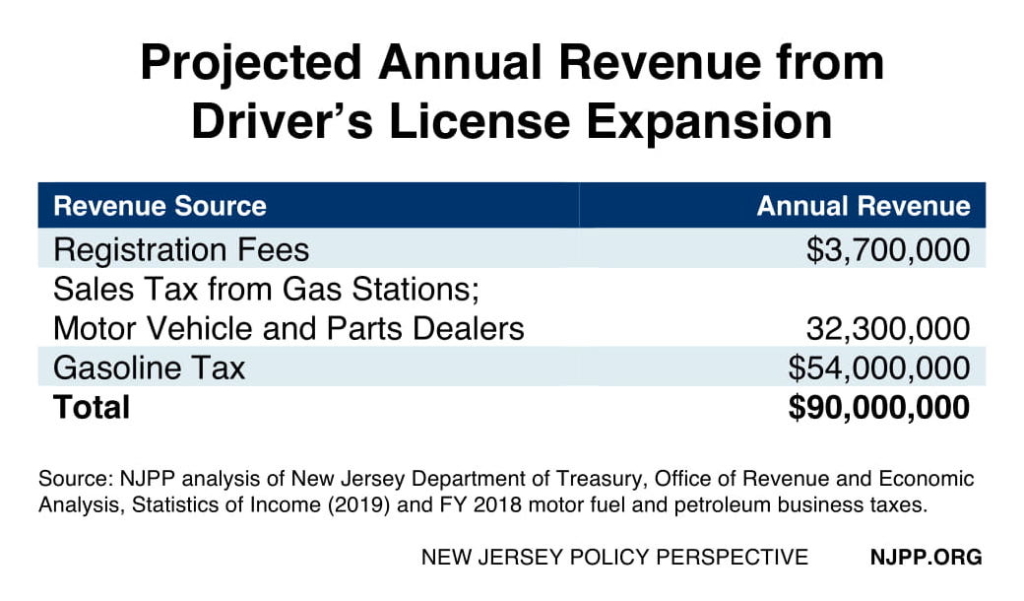

- Expanding access to driver’s licenses for all qualified New Jersey residents, regardless of status.

- Increasing funding for a full universal representation program.

- Passing a state executive order, as Washington and Oregon have done, that would prohibit state and local law enforcement agencies, school police, and security departments from using state and local resources to investigate, detain, detect, report, or arrest people for immigration enforcement purposes.

- Passing legislation, such as California’s Trust Act, that would prevent local jails from holding people for longer periods of time just so they can be deported.[vi] This is similar to the Trust Directive from New Jersey’s Attorney General, but codified into law.

End Notes

[i] United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Approximate Active DACA Recipients as of June 30, 2019. September 2019. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/Immigration%20Forms%20Data/Static_files/DACA_Population_Receipts_since_Injunction_Jun_30_2019.pdf

[ii] Svajlenka, Nicole P. What We Know About DACA Recipients, by State. Center for American Progress. September 2019. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2019/09/12/474422/know-daca-recipients-state/

[iii] Ibid 2.

[iv] Spending power is measured as household income after federal, state, and local tax contributions; these data are based on household incomes, which are available in the ACS microdata, see Svajlenka, Nicole P. What We Know About DACA Recipients, by State. Center for American Progress. September 2019.

[v] Ibid 2.

[vi] American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California. https://www.aclunc.org/our-work/legislation/trust-act-ab-4