To read a PDF version of the full report, click here.

Executive Summary

Maintaining a high-quality teaching workforce is critically important for the future of public education in New Jersey. Federal data, however, show cause for concern: New Jersey is producing far fewer teacher candidates than a decade ago. In fact, the number of candidates completing teacher preparation programs has dropped 49 percent between 2009 and 2018. These declines, which are part of national and regional trends, cut across both gender and race. The dwindling number of teacher candidates creates instability in the teaching profession and jeopardizes the ability of students to learn.[1]

While reasons for the decline in teacher candidates are complex, we know that New Jersey’s teachers are paid considerably less than other college-educated workers, even when controlling for age and time worked.[2] Of particular concern is that the evidence suggests fewer college graduates see teaching as a viable career option with adequate compensation. New Jersey must aggressively address these problems if it wishes to retain its status as having one of the best education systems in the nation.

To stem the decline in teacher candidates, New Jersey should work to make the teaching profession more attractive by raising teacher pay, shoring up benefits, and increasing the respect and appreciation shown to New Jersey’s educators.

This report explores enrollment and completion data in teacher preparation programs, gives context around state policy changes affecting education professionals, reviews the level of teacher demand in the state, and examines the change in demographics within the profession over the past ten years.

Background

This past September, NJPP published an analysis of the New Jersey teaching corps entitled, New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019.[3] Among its findings:

- While factors outside of school are the strongest influences on student achievement, teacher quality is the most significant in-school influence.

- The research on teacher quality suggests that qualified people become teachers based, in part, on how well teaching pays compared to other jobs.

- Despite the importance of teachers, there is a significant gap in wages between New Jersey teachers and other college-educated workers in the state, even when accounting for differences in time worked.

- Pensions and health benefits do not fully close the pay gap between teachers and college-educated workers in other professions.

- New Jersey’s teaching workforce is mostly white and female; there is little evidence of a trend toward a more diverse teaching workforce.

- New Jersey’s teacher workforce is aging, suggesting a new wave of retirements in the next several years.

These findings are similar to other analyses, which show a significant pay gap for teachers compared to other college-educated workers.[4] Critics suggest, however, that these studies are flawed in that they don’t fully account for differences in benefits and other non-pecuniary compensation, unmeasured differences in talent between workers, and other factors. Teachers, they argue, are actually well-compensated, even in today’s tightening labor market.

To test these criticisms, this report examines whether more or fewer workers are becoming teachers. If teacher pay and benefits have kept pace with compensation in other sectors, we would expect to see workers respond in kind, and continue to enter the profession at previous rates. Because compensation levels influence workers’ decisions to go into teaching those workers would judge the benefits that teachers receive as adequate to close the teacher pay gap and continue to enroll in programs to prepare to become educators.[5]

The data, however, tell a different story. Fewer workers in New Jersey are electing to enter teacher preparation programs, a clear indication that teaching is not as attractive a career option as it once was.

Findings

Teacher Preparation Programs: Enrollment & Completion

Teacher preparation programs across the United States can be either traditional or alternative. Traditional programs are generally run by institutions of higher education and lead to degrees or credentials that fulfill the requirements for a teaching certification. Alternative programs enroll candidates who have previous subject-matter knowledge; these candidates often are already the teachers of record in a classroom while they participate in their preparation program.[6]

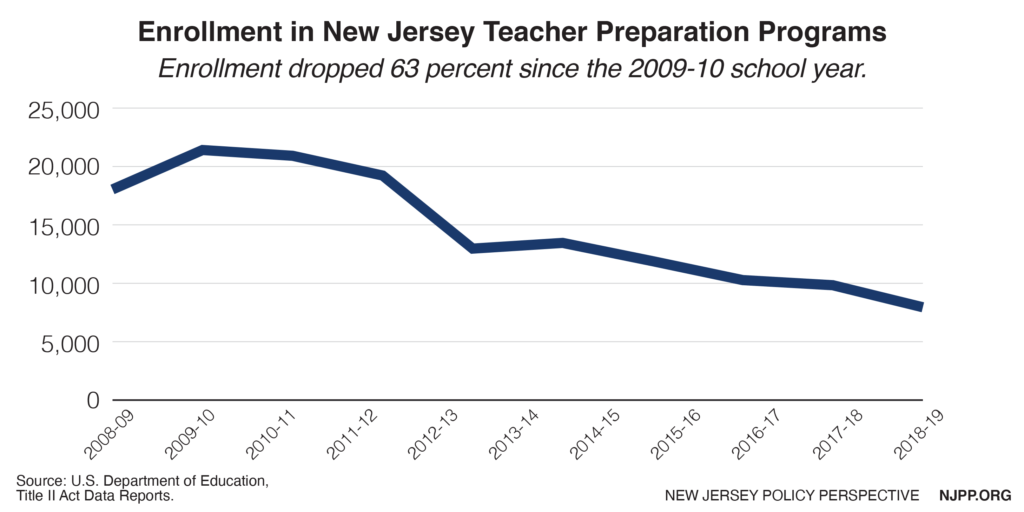

At its peak in the 2009-10 academic year, the state enrolled 21,410 teacher candidates in various preparation programs. By 2017-18, however, the number of enrollees had declined to 7,950, a 63 percent drop.

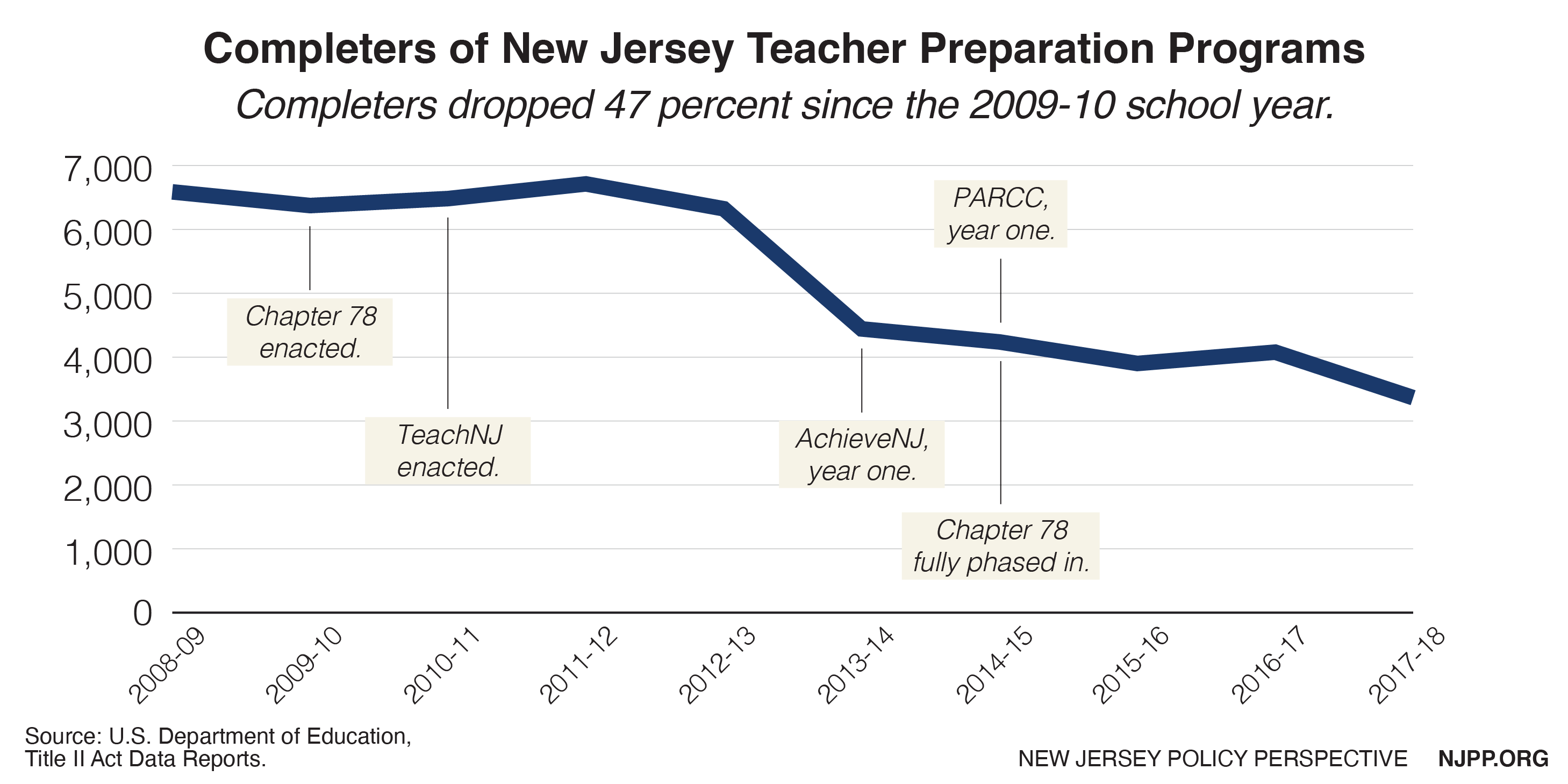

The decline in enrollment led to a decline in the number of people who completed teacher preparation programs (henceforth referred to as “completers”), from 6,373 in the 2009-10 academic year to just 3,366 in 2017-2018, representing a 47 percent decrease.

To contextualize these data, it is instructive to consider the changes in the state’s policies regarding teachers over the same period of time[7]:

- Chapter 78, enacted in June of 2011, was a law that forced teachers to pay substantially higher pension contributions, removed cost of living increases from pensions, and required teachers to pay substantially more for health care benefits.

- TEACHNJ was enacted in August of 2012; it weakened teacher tenure protections, expanded teacher evaluation requirements, and led to the increased use of standardized test scores in teacher rating systems.

- AchieveNJ was implemented by the state for the 2013-14 school year; the new regulations required the use of approved teacher observation systems, as well as the use of Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs) based on test scores, and Student Growth Objectives (SGOs) which require additional work for all teachers.

- The state moved from the New Jersey Assessment of Skills and Knowledge (NJASK) to the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) exams in the 2014-15 school year. PARCC expanded the grade levels subject to testing, increased the amount of time spent administering exams, and required a substantial expansion of technology infrastructure.

It is worth noting that the number of work hours per week reported by teachers increased during this same period. [8] It is likely this is, at least in part, a result of the policy changes listed above.

While reasons for the decline in teacher candidates are complex, these policies likely contribute to working conditions that make it difficult for teachers to thrive. New Jersey’s teachers have been increasingly underpaid relative to similarly educated workers and have seen an erosion of their benefits while the demands of their jobs have grown.[9]

The Demand for Teachers

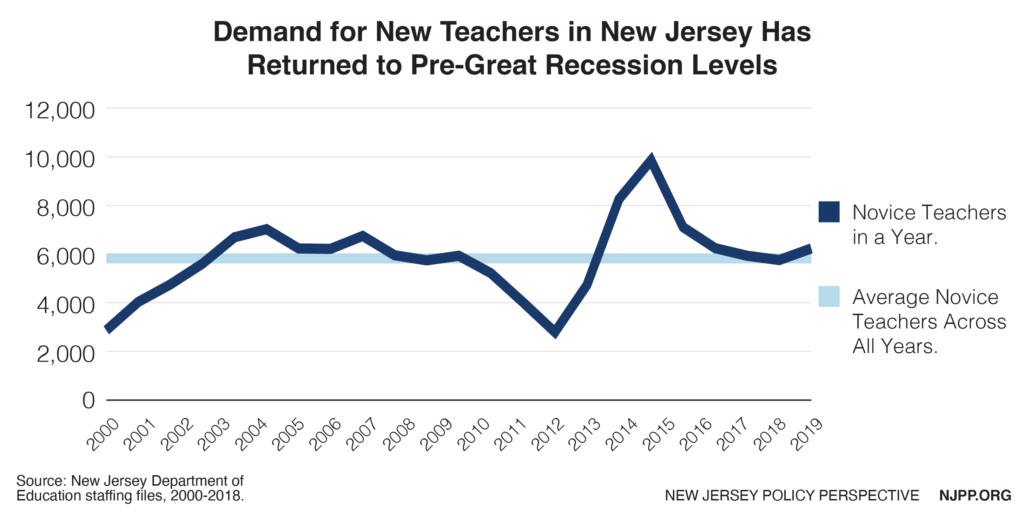

To sustain a strong teacher workforce, it is critical that New Jersey has a large pool of highly qualified candidates for school districts from which to hire. Over the last decade, the number of new teachers entering New Jersey’s workforce has varied sharply. The Great Recession of 2008-09 severely stifled the hiring of novice teachers (certified teachers with less than one year of experience) in New Jersey’s schools. 2009 saw the beginning of a sharp drop off in novice teachers, reaching a low point in 2011. The economic recovery, however, led to a substantial rise in teacher hiring; by 2014, nearly 10,000 novices were in the state’s teacher workforce.

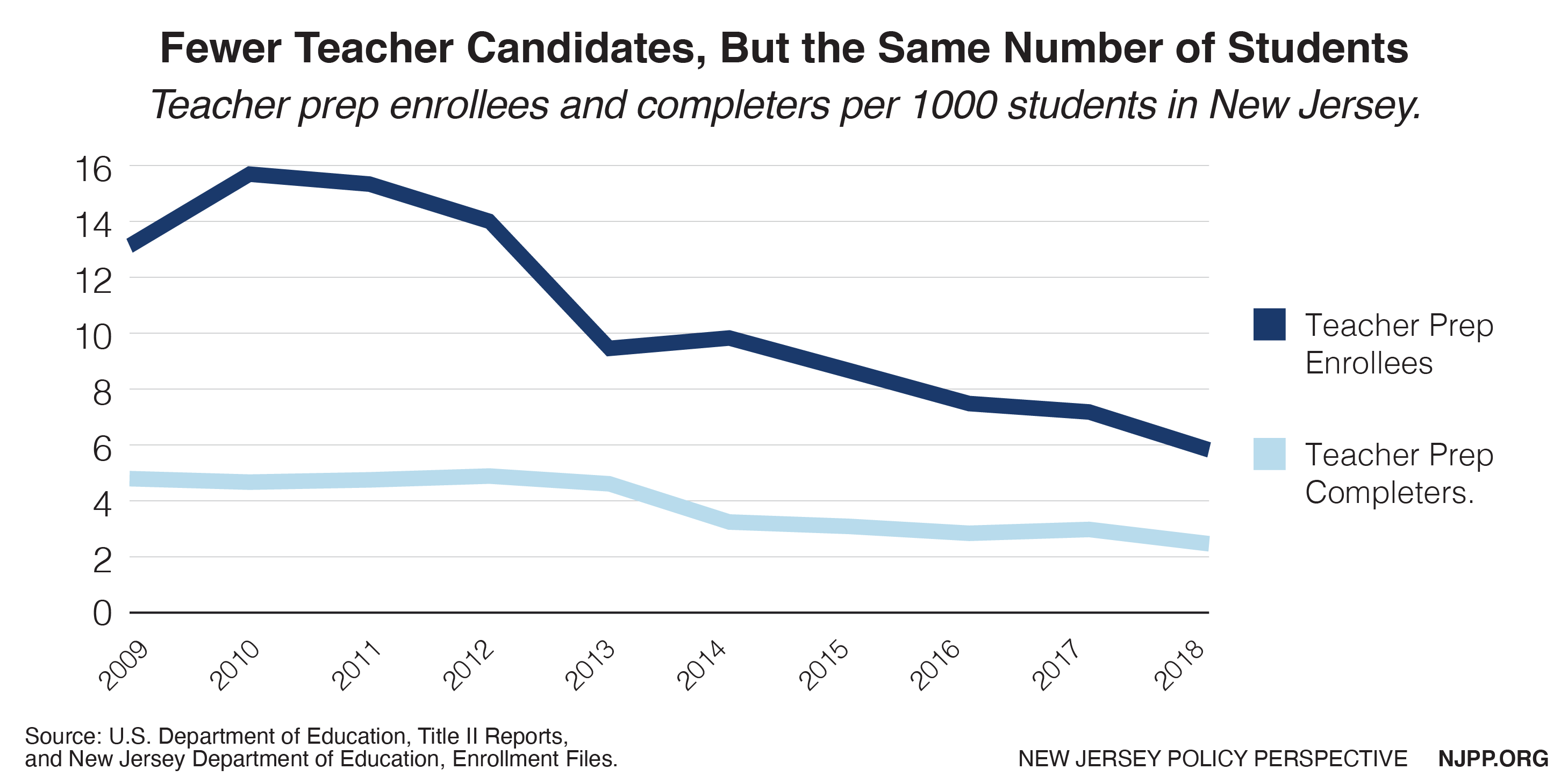

The latest data indicate that New Jersey’s demand for novice teachers is back where it was before the Great Recession. However, the number of teacher candidates has not rebounded – even as the student population has remained relatively stable at around 1.37 million K-12 students from 2009 to 2017. The consequence is that the number of teacher candidates per 1,000 students has dropped significantly.

In 2009, there were about 13 enrollees in teacher preparation programs for every 1,000 students; in 2018, there were only about six enrollees per 1,000 students. Likewise, in 2009 there were nearly five program completers for every 1,000 students; in 2017, there were less than three completers per 1,000 students.

Overall, there are fewer New Jersey workers entering the teaching workforce than a decade ago while the student population has not declined significantly. Each year, school administrators have had to draw from a shallower pool of teacher candidates to fill the positions needed to maintain the quality of New Jersey’s schools. If this trend continues, there will not be enough well-qualified teacher candidates available to maintain the state’s teacher workforce.

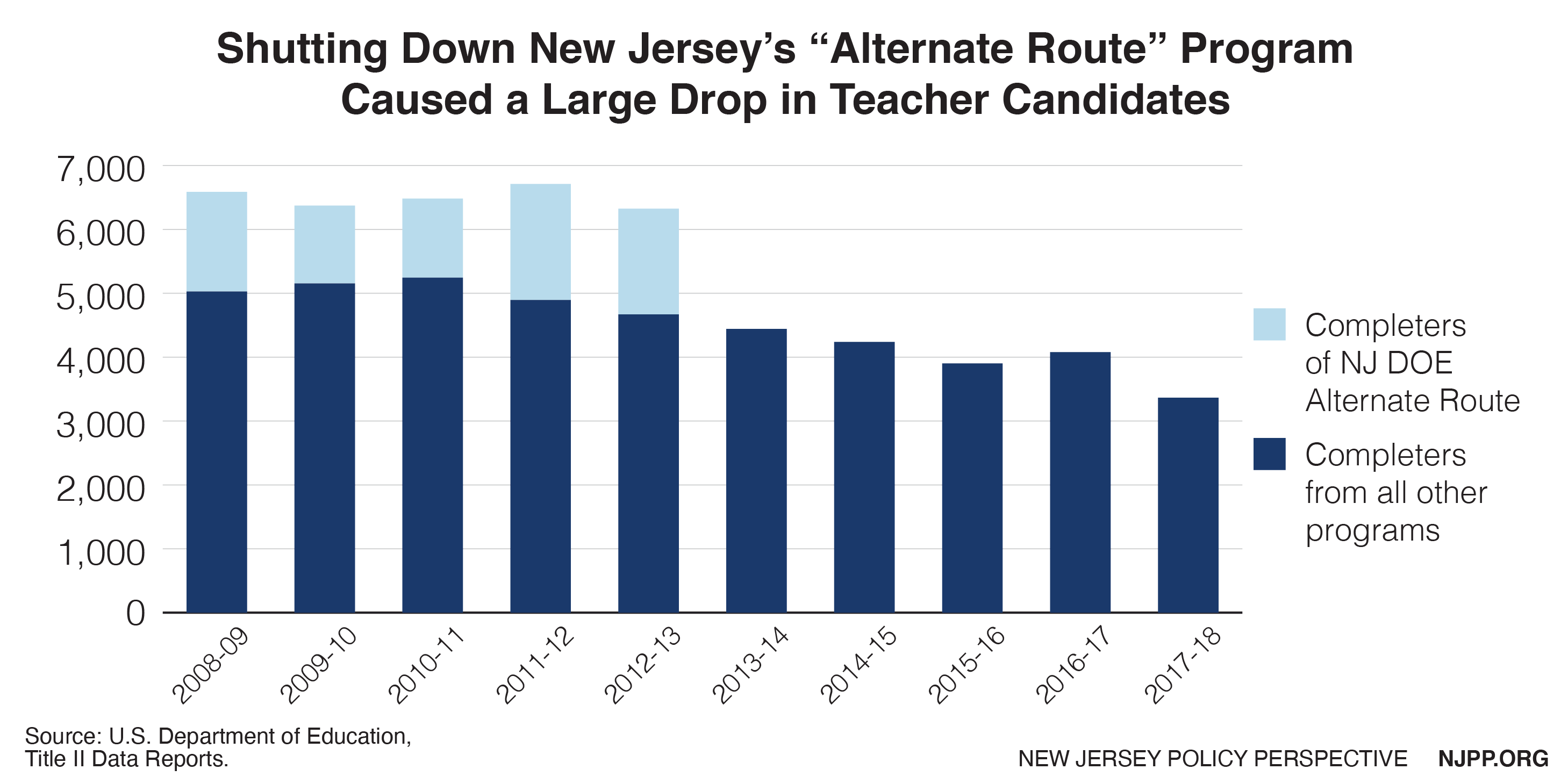

“Alternate Route” Teacher Preparation

Between the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years, there was a large drop in teacher prep program completers. This decline is a direct result of the shuttering of the New Jersey Department of Education’s (NJDOE) Alternate Route program. This program, which was administered directly by the state, allowed candidates with previous subject-matter knowledge to acquire a Certificate of Eligibility (CE) and begin employment as a teacher of record in a classroom. Candidates could eventually become a fully credentialed teacher without enrolling in a traditional program at an institution of higher education (IHE).[10] The state still issues CE’s; however, the Alternate Route program is no longer directly administered by the NJDOE, but by a variety of institutions that also offer traditional preparation programs.

The closing of the NJDOE Alternate Route program brought on a significant decline in the total number of teacher program completers. Further, the number of completers in all other programs also decreased during this time, from a high of 5,243 in 2010-11 to 3,366 in 2017-18, a decline of 36 percent.

When such a large and sudden drop in program completers appears in the data, it is reasonable to ask whether there may be data errors, or some other reporting issue. Conversations with NJDOE staff, however, confirm that the large declines due to the end of the old Alternate Route program were actual declines.[11] Further analysis reveals that New Jersey is not alone; the decline in enrollees and completers of teacher prep programs of all types is a national problem.

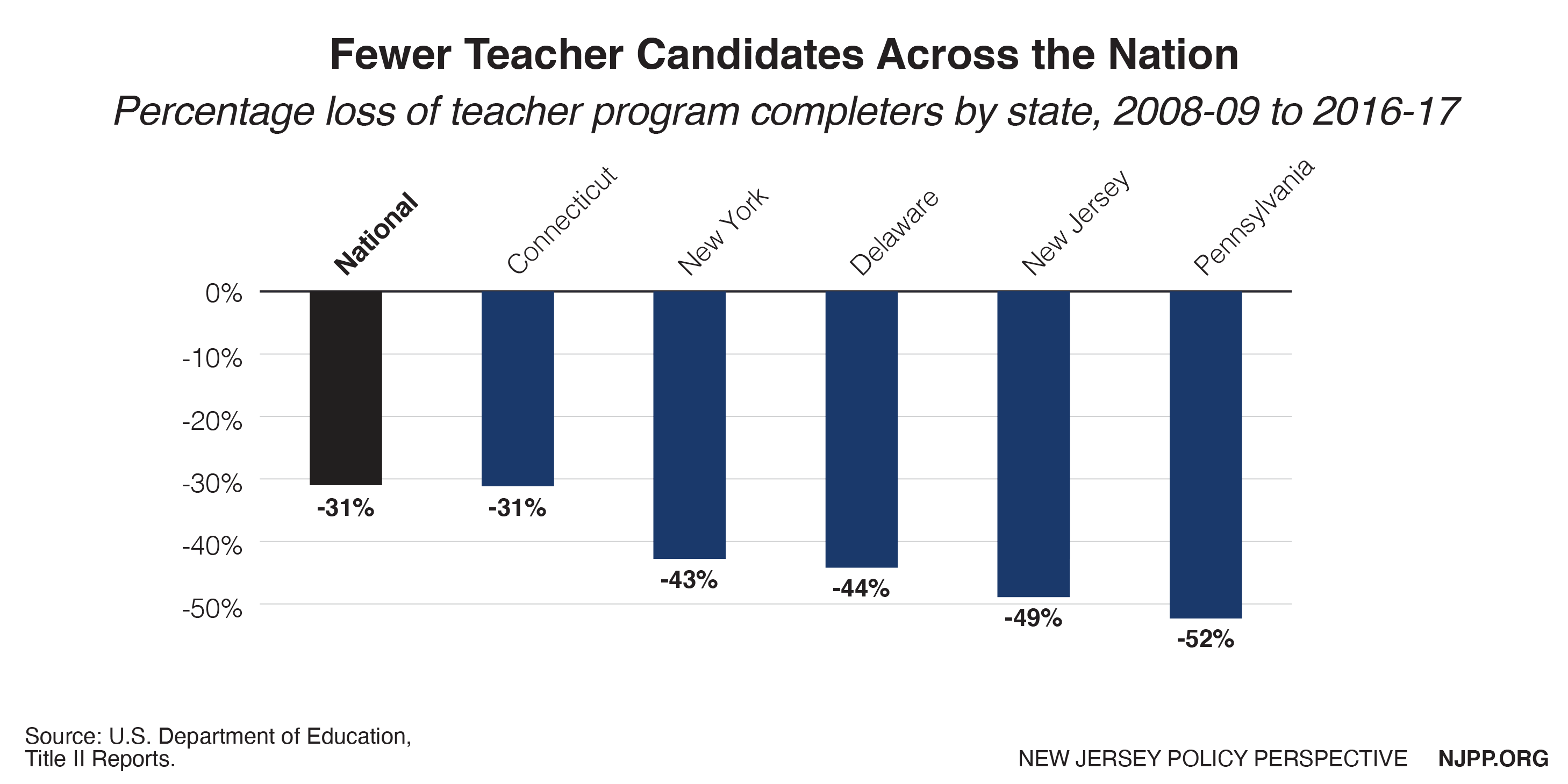

Comparing New Jersey to Neighboring States

The number of teacher candidates is declining across the United States: 31 percent fewer people completed a teacher prep program in the 2017-18 academic year than in 2008-09. New Jersey’s decline of 49 percent is high compared to the rest of the nation, but not when compared to most of its regional neighbors. Pennsylvania had slightly greater losses in teacher candidates during this same period; New York’s and Delaware’s losses were somewhat smaller. Losses in Connecticut, in contrast, were closer to the national average.

Demographics

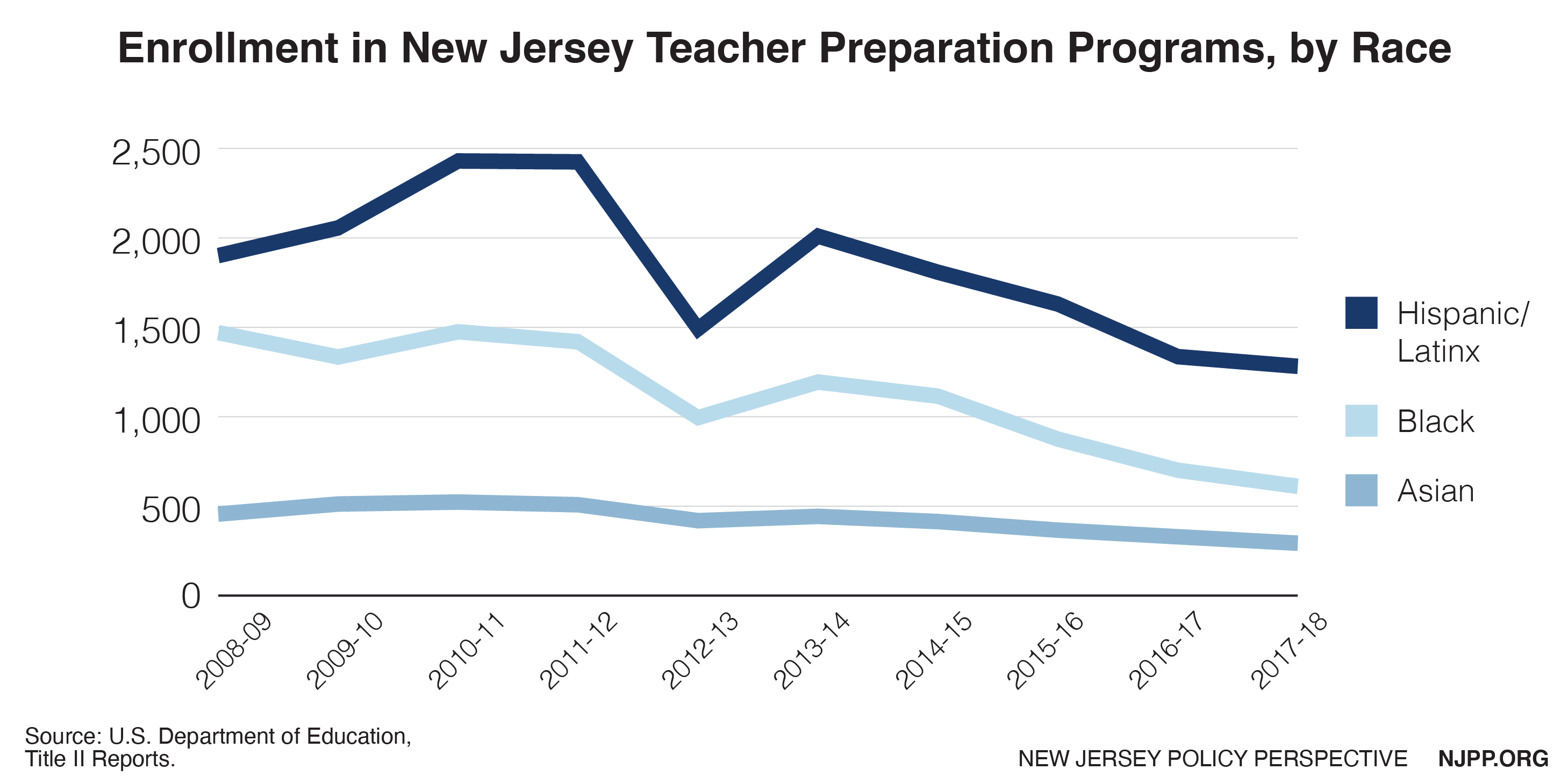

Past research shows students of color benefit from having teachers of color in their schools, reporting that students demonstrate small but significant increases in academic outcomes.[12] Unfortunately, New Jersey’s teacher workforce looks nothing like its student population. While only 22 percent of the state’s students are white females, 66 percent of the state’s teachers are white women.[13]

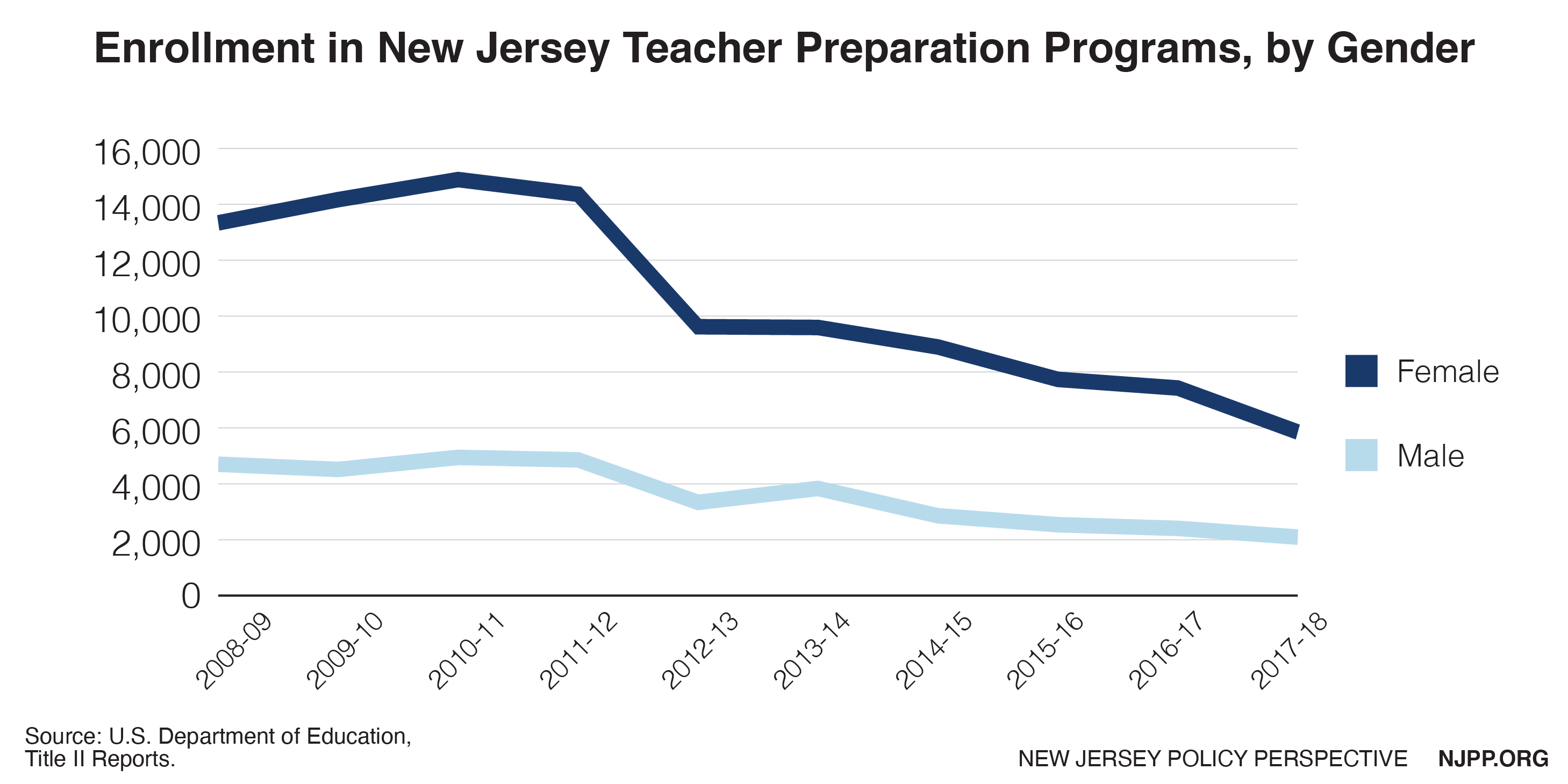

If the state is to have a more diverse teacher workforce, it must recruit a more diverse population of teacher candidates. However, the declines in enrollees in teacher prep programs cut across gender and racial lines.

With regard to gender, between academic years 2008-09 and 2017-18, the number of men enrolled in teacher prep programs declined by 55 percent. During the same period of time, the number of women declined by 56 percent.

While enrollees of different races and ethnicities have all seen declines, there is some variation. Between academic years 2008-09 and 2017-18, Hispanic/Latinx enrollees of any race declined by 33 percent and Asian enrollees declined 36 percent. Even more striking is that Black or African American enrollees declined by 58 percent.

Students of color already face significant challenges in completing college, due to systemic barriers that they are uniquely forced to grapple with. These challenges are compounded when students consider entering a teacher preparation program.[14] Teacher licensure exams, for example, often have higher rates of failure for prospective teachers of color, even as studies find the exams do not consistently or accurately predict teacher effectiveness. There is a disturbing history of deliberate bias in these exams, whose results were often used to justify racially disparate hiring practices in schools.[15]

New Jersey has recently made efforts to recruit more men of color into teaching, but such efforts are likely to have minimal effect if college-educated workers are increasingly turning away from the profession.[16] New Jersey will only recruit a diverse teacher workforce if it both makes teaching more attractive and dismantles the systemic barriers to entry for teacher candidates of color.

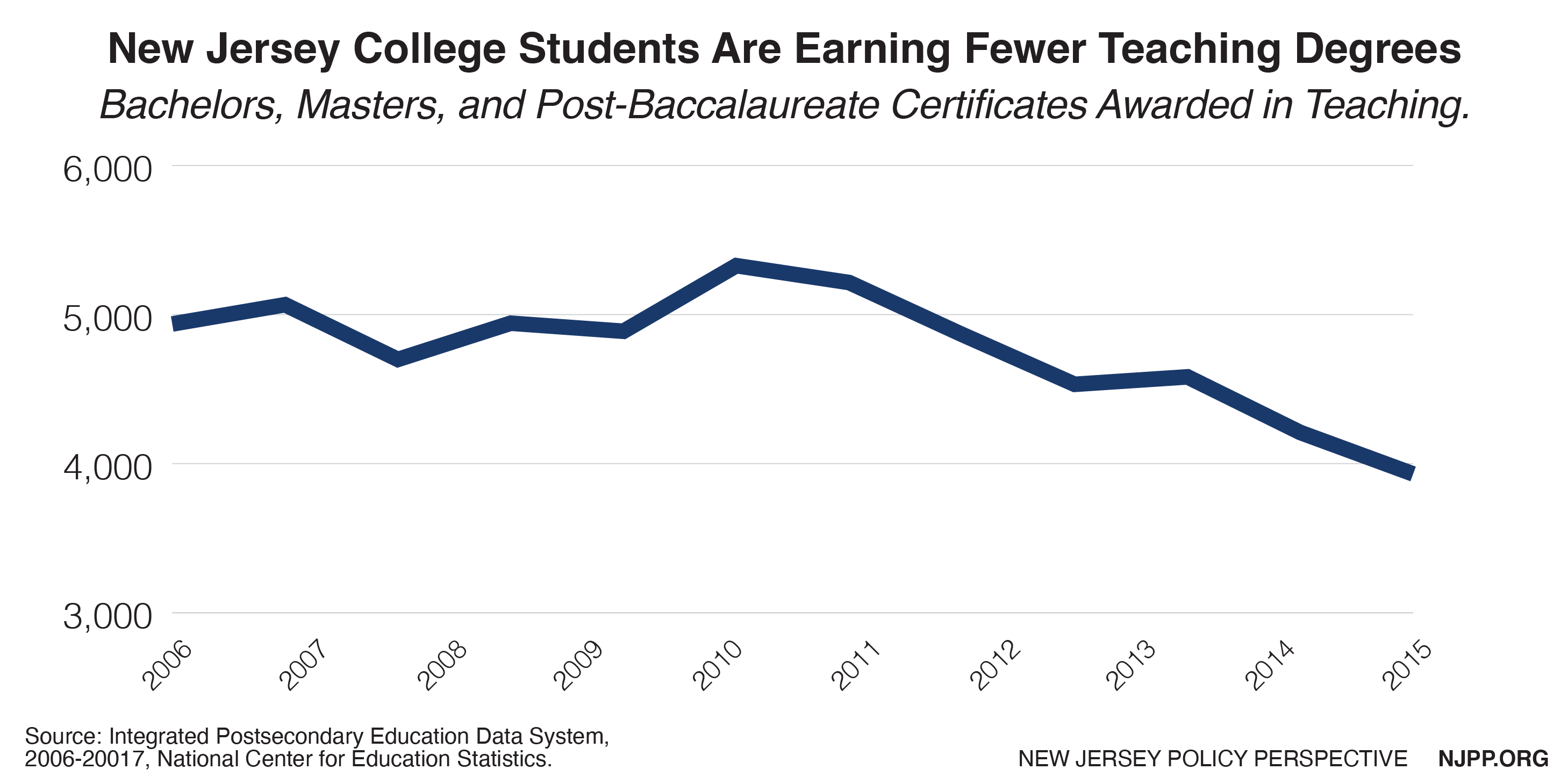

Production of Teaching Degrees

While all certificated teachers in New Jersey must meet specific academic credit requirements, it is not necessary for a teacher to have a degree in education. That said, it is useful to look at the changes in the numbers of New Jersey college students who are granted education degrees by the state’s universities. If teaching has become less attractive to college students, we would expect the number of teaching degrees to decline. The degree production data here comes from a different source than the data above; therefore, any trends here that mirror the trends above bolster the validity of this analysis.

At their peak in 2011, the state’s colleges and universities awarded 5,328 education degrees specific to teaching. By 2017, the number of teaching degrees dropped to 3,911, a decline of 26 percent. Overall, fewer students are pursuing degrees and certificates in teaching than a decade ago.

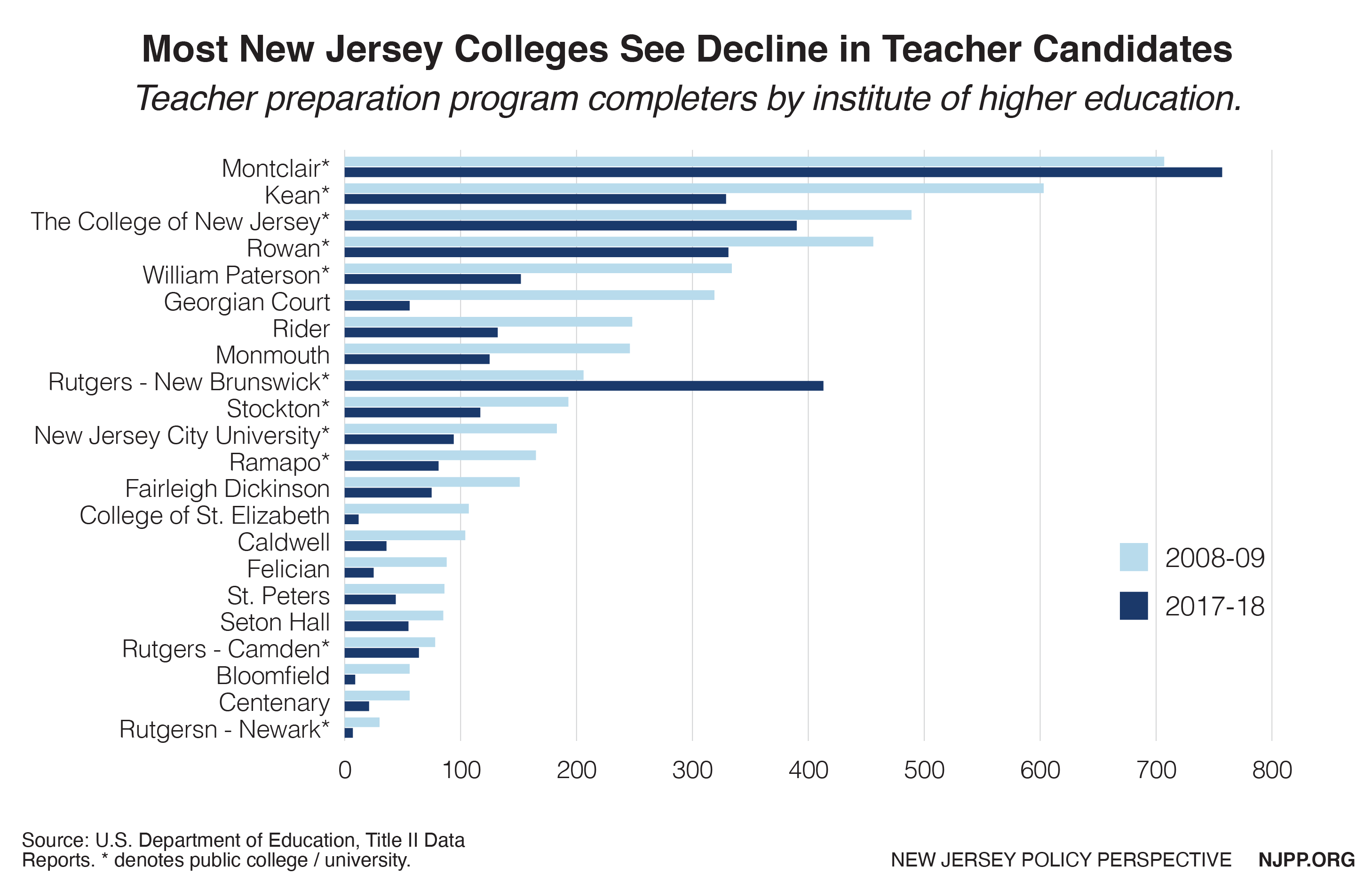

Completers by Institution of Higher Education

While not all teacher candidates pursue degrees in education, institutions of higher education (IHEs) are the primary providers of teacher preparation programs. Federal Title II data break down completers by IHE, allowing us to evaluate program trends and assess which colleges are producing the most teachers.

While there is substantial variation from year-to-year in the number of enrollees and completers, the simplified data here shows the number of teacher prep program completers in 2008-09 and 2017-18. This comparison allows us to look across a substantial number of years at the changes in completion for each IHE.

Montclair State University, the state’s largest teacher program provider, has had a modest increase in completers over this time. Rutgers-New Brunswick has had a substantial increase, although much of this occurred within the last year of the available data. In contrast, the largest decline in teacher prep program completers has been at Kean University, which had almost half the completers in 2017-18 than it did in 2008-09. The College of New Jersey (TCNJ), Rowan University, and William Paterson University have also had notable declines.

New Jersey’s private colleges and universities produce far fewer teacher program completers than its public postsecondary institutions. The most notable decline has been at Georgian Court University, which had 319 completers in 2008-09, but only 56 in 2017-18.

These changes occurred at a time when the NJDOE Alternate Route program, which produced 1,819 program completers in 2011-12, was disbanded. Clearly, New Jersey’s colleges and universities were unable to produce an additional equivalent number of teacher candidates to fill the gap left by the “Alternate Route” program.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The data show that fewer people are entering and completing teacher programs. Working conditions and other factors such as the decline in pay (as compared to other professions), eroding benefits, and punitive policies are likely contributing to the shortage. Given the importance of teachers, the decline in teacher candidates should be a serious concern for New Jersey’s education policymakers. The demand for new teachers has returned to pre-recession levels, but the number of available candidates per 1,000 students has decreased significantly, threatening the state’s quality of education in the long-term.

If New Jersey is to retain its rank as one of the best performing statewide school systems in the United States, it must do a better job of attracting teaching candidates – particularly candidates of color.[17] Toward that end, the following changes are recommended:

- Teacher compensation must rise to attract the best possible candidates into the profession. If we want to attract high-quality candidates into teaching, we must offer teachers competitive wages. Given the rising costs of earning a degree, college-educated workers have more incentive than ever to seek out careers that will maximize the return on their investment in college tuition.[18] Consequently, if we want great teachers, we must offer them a compensation package that reflects the value of their work. Other sectors face the same challenges when determining how to attract and maintain a high-quality workforce — teaching is no different.

- New Jersey must shore up its teacher pension system and stop degrading teacher health care benefits. There is an indisputable wage gap between teachers and other college-educated employees. Good benefits can help close this gap, but New Jersey has, over the past decade, degraded the value of teacher pensions and health care benefits.[19] The decline in enrollees in teacher preparation programs suggests that these policies have had detrimental consequences. The state must take steps to reverse the eroding value of retirement and health care benefits for teachers.

- The state should streamline the process of obtaining a teacher certification as much as possible without sacrificing rigor. Whether the state was previously overproducing teacher candidates is an open question. There is little doubt, however, that the number of teacher candidates has decreased while the number of students has stayed the same. New Jersey should review its certification and preparation programs for teachers to determine whether their requirements impede entry into teaching without adding value to a teacher’s training.[20]

- All of the state’s teacher preparation providers should continue to work together to attract teacher candidates of color. As previous research shows, there are many benefits to having a diverse teacher workforce.[21] New Jersey has recently made commendable efforts to recruit men of color into the profession. These efforts should be evaluated as quickly as possible and, if found successful, expanded.

- New Jersey’s leaders should commit to improving the state’s level of appreciation and regard for its educators. The surest, easiest – and cheapest – way to boost teacher morale is for elected officials to show respect for teachers by acknowledging the importance of their work, giving them a seat at the table when decisions are made about education policy, and refraining from unfairly blaming them for New Jersey’s fiscal troubles.

In a 2018 national poll, 61 percent of superintendents strongly agreed that recruiting and retaining talented teachers would be a challenge for their school district.[22] New Jersey must implement policies to help school district leaders develop and retain the best possible teaching staffs.

Overall, New Jersey’s decline in teacher candidates is a call to action. The state should act immediately to make the teaching profession more attractive, including raising pay, shoring up benefits, and increasing the respect and appreciation shown to New Jersey’s educators.

Technical Appendix

The primary data source for this report is “2019 Title II Reports: National Teacher Preparation Data” from the U.S. Department of Education. https://title2.ed.gov/Public/Home.aspx

Data on teaching degrees is from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), administered by the National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/ To determine the production of teaching-related degrees, I employed this methodology:

- Include only institutions designated as offering teacher certification.

- Include only bachelors and masters degrees, and post baccalaureate certificates.

- Count all degrees awarded in education (cipcode “13”).

- Count all degrees in curriculum and instruction; educational administration and supervision; educational/instructional media design; educational assessment, evaluation, and research; social and philosophical foundations of education; teaching assistants/aides; and education, other.

- Subtract this count from the total count of education degrees.

Student counts to determine teacher candidates per 1,000 students are from the New Jersey Department of Education’s fall enrollment files. https://www.nj.gov/education/data/enr/

Staffing counts of novice teachers come from New Jersey Department of Education staffing files, which were obtained through Open Public Records Act (OPRA) requests.

Citations for New Jersey teacher policy changes in Figure 2 are as follows:

- Chapter 78 enacted June 28, 2011: https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/pensions/reform-2011.shtml

- TEACHNJ signed into law August 6, 2012: https://www.njspotlight.com/2012/08/12-0805-2127/

- AchieveNJ year one, 2013-14: https://www.nj.gov/education/genfo/faq/faq_eval.shtml

- PARCC year one, 2014-15: https://www.state.nj.us/education/archive/sca/parcc/

- Chapter 78 full phase-in, July 2014: https://www.nj.gov/treasury/pensions/documents/hb/oe2018/ha0885-monthly19.pdf

About the Author

Mark Weber is the Special Analyst for Education Policy at the New Jersey Policy Perspective. He is also a full-time public-school teacher in Warren Township (where he won the Governor’s Award for Excellence in Education in 2018), and a lecturer at Rutgers University in public school finance. Weber is the author of numerous academic papers on education policy, as well as many policy briefs published by the National Education Policy Center, the Albert Shanker Institute, the Education Law Center, the New Jersey Education Policy Forum, and others. Weber holds a Ph.D. from Rutgers University in Education Theory, Organization, and Policy.

End Notes

[1] García, E., & Weiss, E. (2019). U.S. schools struggle to hire and retain teachers. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/u-s-schools-struggle-to-hire-and-retain-teachers-the-second-report-in-the-perfect-storm-in-the-teacher-labor-market-series/

[2] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[3] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[4] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, p. 38. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[5] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 7-8. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[6] Preparing and Credentialing the Nation’s Teachers; The Secretary’s 10th Report on Teacher Quality. (2016) U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education. https://title2.ed.gov/Public/TitleIIReport16.pdf

[7] See the Technical Appendix for citations in this section.

[8] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, p. 36-37. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[9] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, p. 23-25. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[10] State of New Jersey, Department of Education, “New Teacher Guidance.” https://nj.gov/education/newteacher/

[11] Conversation with NJDOE staff, November 25, 2019; thanks to all the staff members who generously gave their time for this conversation.

[12] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 5-6. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[13] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 15-19. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[14] Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the Teaching Profession: How to Recruit and Retain Teachers of Color. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Diversifying_Teaching_Profession_REPORT_0.pdf

[15] As Carver-Thomas (2018) notes: “An analysis of teacher test design later indicated that cultural bias contributed to disparate test score outcomes. Researchers found that when a version of the NTE general knowledge test replaced traditional questions with test items based on Black culture, Black women scored higher than White women. The reverse was true when questions were drawn exclusively from non-Black culture.” (p.13)

[16] O’Dea, C. (May 13, 2019). “NJ Makes Move to Recruit More Men of Color as Teachers.” NJ Spotlight. https://www.njspotlight.com/2019/05/19-05-12-nj-makes-move-to-recruit-more-men-of-color-as-teachers/

[17] Lloyd, S.C. and Harwin, A. (September 3, 2019). “In National Ranking of School Systems, a New State Is On Top.” Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/09/04/new-jersey-tops-national-ranking-of-schools.html

[18] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Digest of Education Statistics, 2017 (NCES 2018-070), Chapter 3. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=76

[19] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 26-28. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists. See also: Jeffrey H Keefe, “New Jersey Public School Teachers Are Underpaid, Not Overpaid” (Economic Policy Institute, February 15, 2017), https://www.epi.org/publication/new-jersey-public-school-teachers-are- underpaid-not-overpaid/

[20] As an example: in 2015, the state began requiring that teacher candidates participate in edTPA, an evaluation system for teacher candidates that requires the submission of video recordings of teaching as part of a portfolio. Yet a recent evaluation of edTPA calls into question the reliability of its assessments; see: Gitomer, D. H., Martínez, J. F., Battey, D., & Hyland, N. E. (2019). Assessing the Assessment: Evidence of Reliability and Validity in the edTPA. American Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219890608

[21] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 5-6. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists

[22] “Gallup 2018 Survey of K-12 School District Superintendents” https://www.gallup.com/education/241151/gallup-k-12-superintendent-report-2018.aspx