This is Part 1: Series Overview and a Plan for the Future of School Funding in New Jersey: A Fair Future for All. Click the links below to access Parts 2 through 5.

Part 2: School Resources, Revenue, and Taxes

Part 3: The School Funding Reform Act – 2020 Update

Part 4: The Cost of an Adequate Education in New Jersey

Part 5: Inequities Within School Districts

NJPP’s second annual report on the state of school funding in New Jersey arrives at a time of unprecedented challenges, both fiscal and educational. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced school districts to radically change how they deliver instruction, while the ensuing economic downturn has created a fiscal crisis for both the state and its local school districts. Ironically, the looming threat of cuts to education spending comes at a time when there is a stronger research consensus than ever about the role of funding in student academic achievement: Adequate and equitable school funding is the necessary precondition for student success. If New Jersey is to see its students thrive through this emergency, it must find a way to ensure that all children, no matter where they live or what learning challenges they face, have access to schools that are adequately funded.

This series, School Funding in New Jersey: A Fair Future for All, provides an in-depth look at the current state of school finance in New Jersey: how the state got here, what the consequences have been for our students, and how the state should proceed in the face of the current crisis.

In Summary

Principles

- School districts enrolling more children from low-income families and more English language learners need more resources to equalize educational opportunity. These are the same districts, however, that are at a disadvantage in raising revenues from the onset, because their tax capacity is lower.

- A state school funding system, therefore, should drive more funding to the districts that need it most, but have the least capacity to raise it themselves. In other words, statewide school funding should be progressive.

- Acknowledging the revenue inequities that arise from property taxation, property taxes remain an important revenue source because they are less volatile and, therefore, less likely to decline in an economic slump.

- State aid to schools is tax relief: it makes state and local taxes more progressive because it distributes the tax burden more equitably.

- Fewer resources mean fewer staff per student and less-competitive wages for staff. Districts with proportionally more students requiring additional support, including those who are economically disadvantaged, English language learners, or children with disabilities, benefit from having these resources.

Key Findings

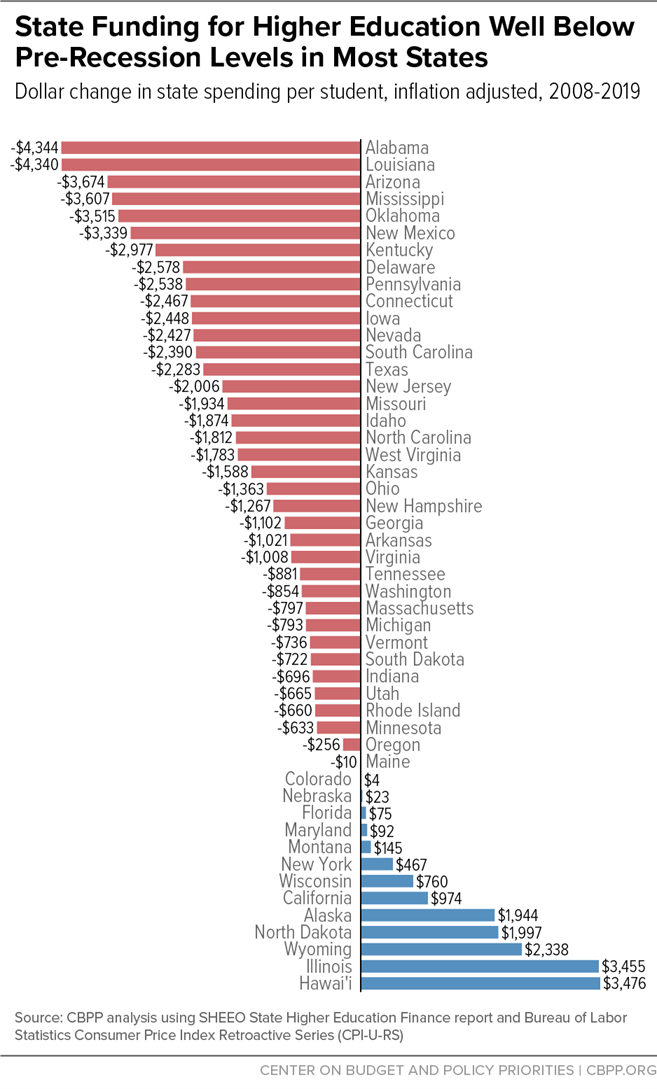

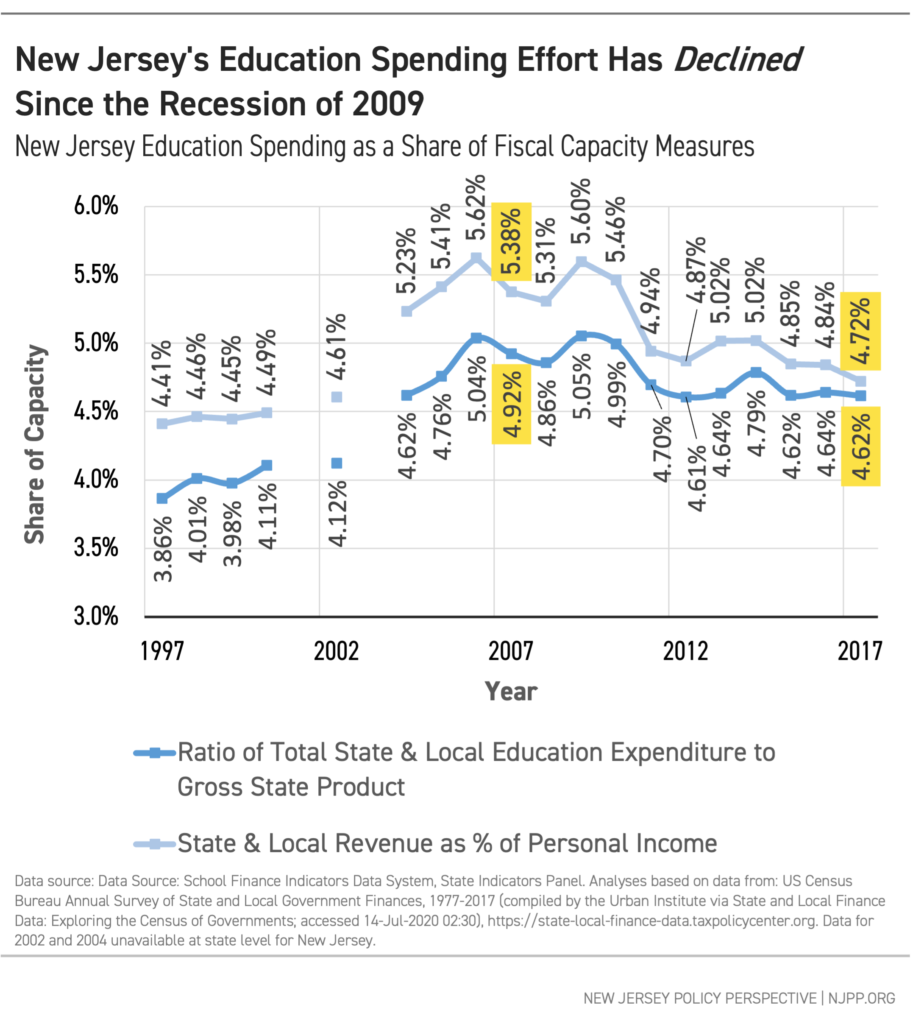

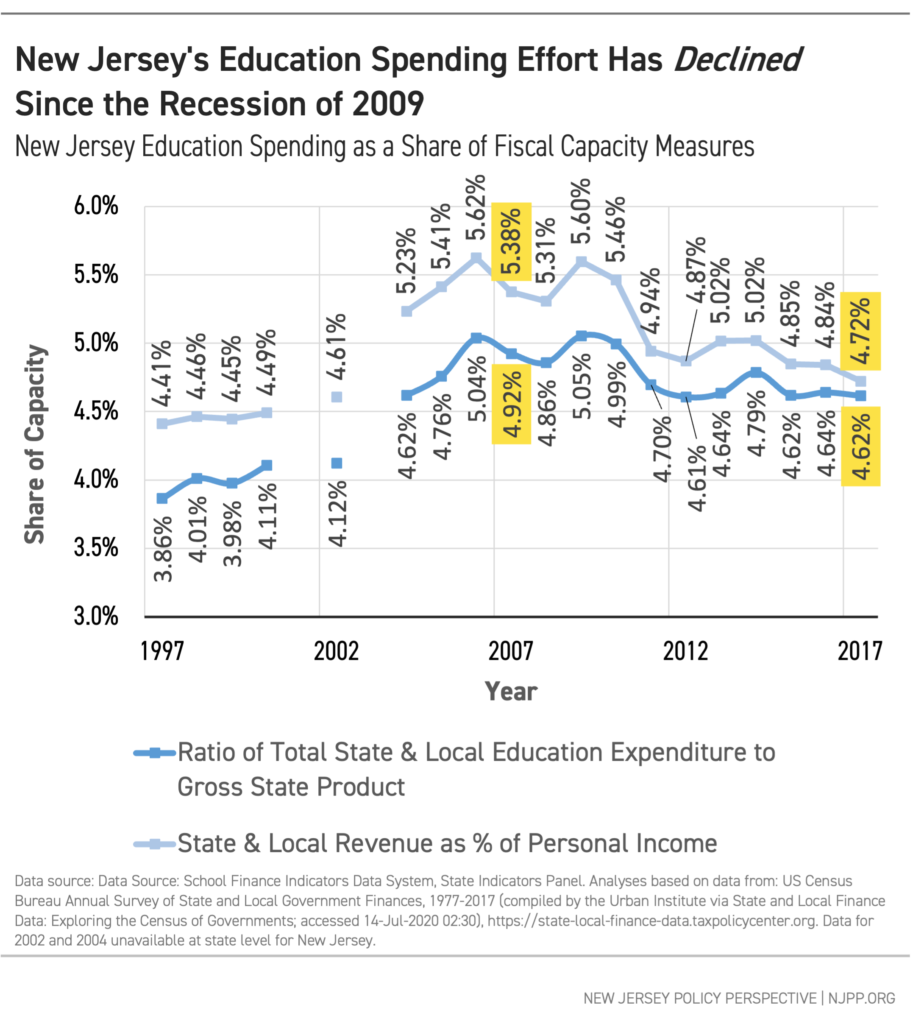

- Compared to other states, New Jersey still makes a strong effort to fund its schools (“effort” being the proportion of the state’s economy dedicated to K-12 education). But New Jersey has made less effort to fund schools after the recession of 2009 than it did before; the state has never made up for the losses in school revenues following the recovery. Consequently, New Jersey school districts are in a worse fiscal position now than they were before the last recession.

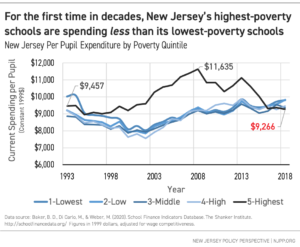

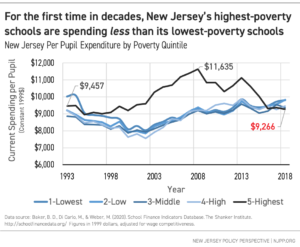

- New Jersey has gone backwards in school funding progressiveness over the past decade. For the first time in decades, New Jersey’s highest-poverty schools are spending less than its lowest-poverty schools. This said, New Jersey’s underlying school funding formula is more progressive than in many other states.

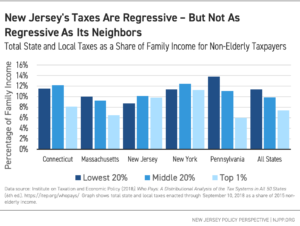

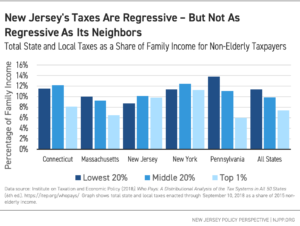

- New Jersey is not a tax-and-spend outlier: it ranks 31st in the nation on own source revenues, and 8th in the nation on state and local taxes (as a percentage of income). New Jersey has more progressive state and local taxes than its neighbors; however, the wealthiest residents of New Jersey still pay less in taxes than those in the middle. New Jersey’s state school aid system is one of the reasons its taxes are less regressive.

- New Jersey’s School Funding Reform Act (SFRA) is designed to drive more funding to districts with greater needs but lower tax capacity. But SFRA spending targets were set based on older and lower standards for student learning; to reach the new, higher standards, students and schools will need more resources. In addition, SFRA has features that drive aid toward districts that are already spending well above adequacy targets. For example: the funding formula allocates some state aid for special education to every district regardless of whether it spends above its adequacy target. The result is that the wealthiest districts with the greatest capacity to raise their own revenues still receive funding under SFRA.

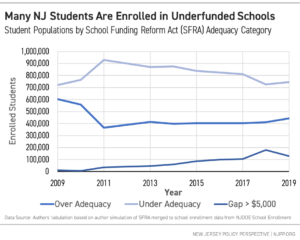

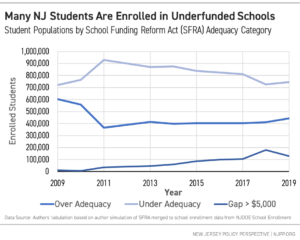

- More school districts are falling below their spending targets in 2019 than they were in 2010, the first year of SFRA. This is because many districts have not received the state aid they need, and some districts are not making their local required effort to fund their schools. The students in underfunded districts are more likely to be English language learners and come from low-income families. Research shows that these students need additional resources to achieve equal educational opportunity.[1] The SFRA formula was designed specifically to address this reality; continually underfunding these districts, therefore, undermines the primary goal of the law.

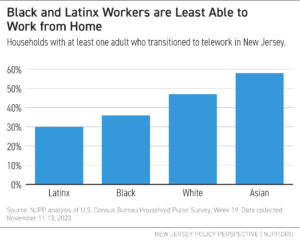

- Under-spending districts – those with current spending below their SFRA specified adequacy targets – have higher concentrations of Black and Latinx students, and fewer teachers per 100 students. Many of these districts were not Abbott districts: they have never enjoyed the extra funding that came to districts that were party to the Abbot

- The Governor’s budget for this year – released before the pandemic – was moving more state aid toward traditionally underfunded districts, although not enough to make up for historical funding gaps.

- Analysis from our National Education Cost Model (NECM) shows New Jersey spends more than other states on schools; consequently, the state’s outcomes are higher than other states. Yet there are some districts in New Jersey, serving proportionally more students in economic disadvantage, that do not spending enough to meet the modest goal of national average outcomes.

Recommendations

- Given the economic impact of the current pandemic and the increased costs of operating schools safely, all of New Jersey’s education stakeholders must unite and press for federal aid for schools. In addition, the state must consider raising additional revenues from its wealthiest residents, who pay less in taxes proportionally than middle-class residents.

- In the face of the coming economic downturn, New Jersey should maintain and enhance the features of its school aid system that promote school funding progressiveness while decreasing tax regressiveness.

- If cuts in state aid need to be made this year, New Jersey should first target the aid flowing to high-tax capacity districts, including categorical aid that is allocated outside of the adequacy formula.

- If cuts in state aid need to be made, it is better to apply those cuts as a share of school district budgets, and not as a percent of state aid. Cutting aid as a share of aid will harm the highest-poverty, lowest-capacity districts more – those that are more dependent on aid to begin with.

- SFRA spending targets should be recalibrated to align with new, higher standards; currently, they are too low, as they were based on previous, less rigorous outcome goals. Recalibration of the formula can occur without legislative change, a primary objective of the three-year Educational Adequacy Reports.

- Judicial actions are not enough to ensure all of New Jersey’s students receive adequate funding: the state must take legislative and administrative actions to resolve the underfunding of many of its school districts, particularly those that do not have standing under the Abbott

- New Jersey should stem the increase in the number of small, autonomous school districts, which tend to be less efficient than larger districts.

- The state should conduct analyses of within-district spending differences, not local districts. These analyses should take into account drivers of cost differences such as special education, student characteristics, grade levels, and school type (magnet, charter, etc.). The methods described in this report will provide reasonable, actionable information for schools to more equitably allocate resources.

School Funding in New Jersey: An Overview

Years of research confirm an inescapable fact: Equitable and adequate funding is a prerequisite condition for providing a quality elementary and secondary education system. In past decades, when school funding has been increased students have benefited from those increases, demonstrating better outcomes in a range of educational measures.[2] Conversely, when school funding has been cut, students have suffered the consequences. Several recent studies reveal the adverse effects of the Great Recession of 2008 on student achievement.[3] Unfortunately, while adequate school funding is necessary for student success, public school systems across the country are currently bracing for an unprecedented economic recession resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Worse, most of these school systems, including schools in New Jersey, have still not fully recovered from the drastic cuts in school funding caused by the Great Recession.

NJPP’s first annual report on the state of New Jersey’s School Funding Reform Act (SFRA), released in 2019, addressed the first decade of the implementation of SFRA (2008 to 2018), the effects of the great recession on SFRA, and the failure of the state to fully recover and fund SFRA as designed.[4] As of that report, New Jersey had still not fully funded its school aid formula, and many districts faced significant gaps between their current spending levels and spending levels estimated in the formula as needed to achieve desired outcomes. Most of these spending gaps were a function of school districts failing to receive sufficient state aid because the state failed to fully fund its own formula. But some other districts fell below their “adequacy” targets because those districts failed to provide their full local contribution. Notwithstanding minor technical changes to the formula recommended in our first-year report[5] that have not been addressed, the long-term issues remain the same. New Jersey must both move toward fully funding the formula as it stands, while simultaneously considering the recalibration of that formula to today’s outcome goals and standards, as well as an increasingly diverse student population.

And yet New Jersey faces a severe fiscal crisis in the days ahead. The shock of the sudden economic shutdown will undoubtedly affect school budgets for years to come. Tax revenues will be lower as activity slumps, even as the state will have new public health spending obligations as it manages the effects of the pandemic. At the same time, it is impossible to imagine New Jersey making a meaningful recovery without adequately funded schools. A well-educated populace is the backbone of a strong economy, particularly in New Jersey, with its high rates of college attainment.[6] The state must not abandon its constitutional obligation to provide a “thorough and efficient system of free public schools” for its children; in fact, it will likely have to increase spending on schools given the realities of COVID-19. As the authors of this report have noted elsewhere:

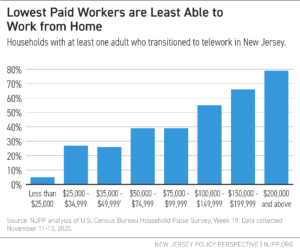

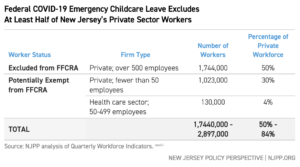

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, public schools will likely experience even greater revenue losses in the coming years than they did during the Great Recession. Further, it appears that safely reopening schools in the fall of 2020 will itself be costly. Much smaller class sizes will be required to meet social-distancing guidelines and contain the spread of the coronavirus; this, in turn, will require hiring additional personnel, finding new classroom space, and perhaps creating staggered schedules. It will mean more instructional hours for teachers, more staff hours spent cleaning and sanitizing facilities, and more complicated bus routes. Schools will have to budget for additional time and effort from maintenance and operations staff, food service workers, and other support positions. Nursing and other medical services — already inadequate in many schools (Willgerodt, Brock, & Maughan, 2018) — will need to be improved. And, to ensure equitable internet access, districts will have to redouble their investments in broadband and portable computers. Finally, since learning losses due to this spring’s school closures are likely to be most severe for students who live in poverty (Herald, 2020; Rothstein, 2020), schools in low-income neighborhoods will face especially daunting challenges come September. In short, we can expect the costs associated with reopening schools to be significantly greater this fall than in previous years, particularly in high-poverty schools and districts.[7]

Never has New Jersey been in such need of good school funding policy, grounded in high-quality research and sound analyses, that balances the needs of New Jersey’s children – especially its most disadvantaged children – with the state’s current fiscal realities. This series of reports strives to clarify the issues before the state regarding school funding by explaining where New Jersey is currently regarding K-12 education spending, how it arrived here, and the consequences of its school funding choices. This research lays the foundation for a school funding plan, as presented below.

Series Summary

Part 2: School Resources, Revenues, and Taxes

This report focuses on two of the three core indicators of statewide school funding fairness and effectiveness: effort and progressivity. Effort is a measurement of how much of a state’s economic capacity is directed toward K-12 education. Progressivity measures how much more (or less) a state’s neediest school districts receive relative to its most affluent. Compared to other states, New Jersey makes a strong effort to fund its schools: it devotes more of its economic capacity to education funding than most other states. Unfortunately, New Jersey decreased its share of economic capacity allocated to elementary and secondary school funding since the last recession. New Jersey’s high-poverty districts have suffered the greatest consequences of these reductions. Even though New Jersey exerts high effort relative to other states, it made less effort to fund schools after the Great Recession of 2009 then it did before. The state never made up for these losses in school revenues following the recovery; consequently, New Jersey has lost its position as the leader in progressive financing of schools.

New Jersey’s effort to fund schools is directly tied to its taxation system. Complaints about all taxes are a regular feature of political debates in New Jersey; however, New Jersey is not a tax-and-spend outlier. The state ranks 31st in the nation on own source revenues, and 8th in the nation on state and local taxes (as a percentage of income).[8] New Jersey also has less regressive state and local taxes than its neighbors: while the wealthiest residents still pay less in state and local taxes than those in the middle, New Jersey’s overall tax system does put more of the tax burden on its wealthiest citizens compared to many other states. An important reason for this relative progressiveness in taxes is the New Jersey school aid system. State aid to schools is tax relief: it makes state and local taxes more progressive because it distributes the tax burden for schools more equitably. New Jersey’s state school aid system is one of the primary reasons its taxes are less regressive here than they otherwise would be.

There are a multitude of problems with property taxation for local public goods and services, including schools. They are inequitable, both in terms of the revenues they generate and in terms of how they fall on local taxpayers. They tend to be regressive, with low income taxpayers paying a larger share of their income in property taxes. Many of these disparities are derived from over a century’s worth of manipulation of real estate markets, often with the primary goal of racial exclusion of home ownership in suburbs and orchestrated urban racial isolation through placement of low-income housing projects. Add to this the distortions in local tax rates created by placement of high value, though undesirable, industrial and utility properties.

But there’s one undeniable truth about revenues from property taxes that make it difficult, if not implausible, to eliminate them altogether from the revenue portfolio for schools: property tax revenues are far more stable than income or sales tax revenues. Fiscal planning for local public school districts, including maintenance of an equitable and adequate system of schooling, requires a balanced revenue portfolio inclusive of stable sources. The goal, moving forward, should be to identify the best strategies and creative policy options for taking advantage of the stability of property tax revenues while mitigating the inequities they have historically yielded.

While New Jersey is moderately better than most states at progressively funding its schools – driving funding where student needs are greatest and tax capacity is lowest – for the first time in decades, New Jersey’s highest-poverty schools are spending less than its lowest-poverty schools. This slide toward regressive funding has real and educationally meaningful consequences: New Jersey’s least affluent schools have fewer teachers per student and less competitive teacher salaries than they did before the recession of 2009.

In the face of an economic slump, federal aid for schools is critically important for all other states to operate safe and healthy schools in the coming years. New Jersey must also consider additional state taxes, targeted to its wealthiest residents, who still pay proportionally less than the state’s middle class.[9] If adequate federal and state aid isn’t forthcoming, however, New Jersey may be forced to consider cuts in state aid. In the previous recession, New Jersey (unlike other states) chose to make cuts based on a percentage of school budgets, and not on a percentage of state aid. This was a better – though still imperfect – approach that caused less harm to districts serving the most disadvantaged students. This report includes a simulation of cuts using both approaches; while neither is ideal, the harm to the districts enrolling students in the highest poverty quintile is clearly less when cuts are made based on school budgets.

Part 3: The School Funding Reform Act – 2020 Update

New Jersey’s School Funding Reform Act (SFRA) is designed to drive more funding to districts with greater needs but lower tax capacity. These are districts with lower property values; consequently, they must have much higher taxes rates simply to raise equivalent funds for their local schools. Students in these districts are more likely to be English language learners (ELL) and come from low-income families: these are the students research shows need more resources to achieve equal educational opportunity. SFRA, therefore, makes school funding more fair for both taxpayers and students.

Providing more funding to districts with higher concentrations of ELL and lower-income students is a common feature of state aid formulas, backed by a large body of research. ELL students require teachers with particular skills and training, as well as appropriate instructional materials and assessments.[10] While the amount varies across state contexts, there is no doubt that extra resources are needed to provide ELLs with effective instruction.[11] Similarly, modern research confirms that additional resources for lower-income students – used to reduce class sizes, lengthen instructional time, and increase educator salaries – yields significant and positive results.[12]

Unfortunately, tracking the funding of SFRA shows the collapse of progressive funding in New Jersey over the past decade. More school districts are falling below their spending targets in 2019 than they were in 2010, the first year of SFRA. This is because many districts have not received the state aid they should, and some districts are not making their local required effort to fund their schools. A common feature of districts falling well below SFRA funding targets (more than $5,000) is that they serve predominantly Latinx and low-income student populations. Schools in districts with larger funding gaps have fewer certified staff per pupil, and have less competitive teacher wages for otherwise similar teachers.

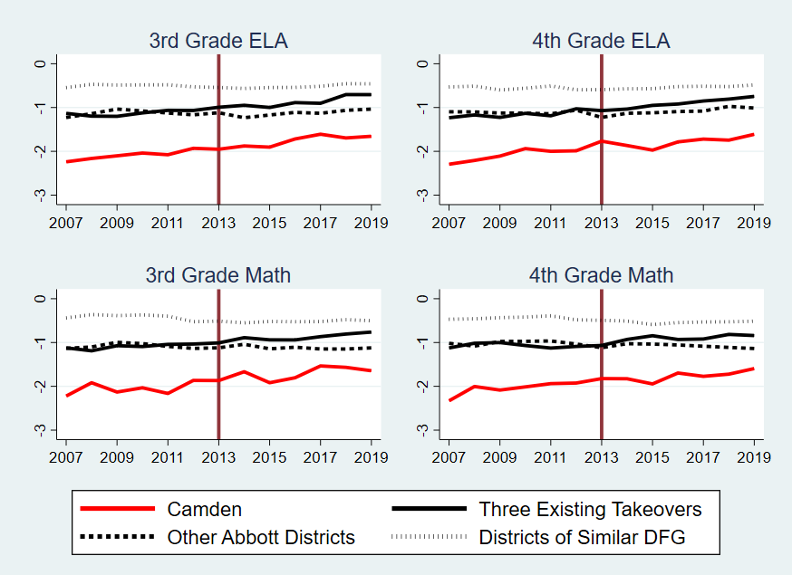

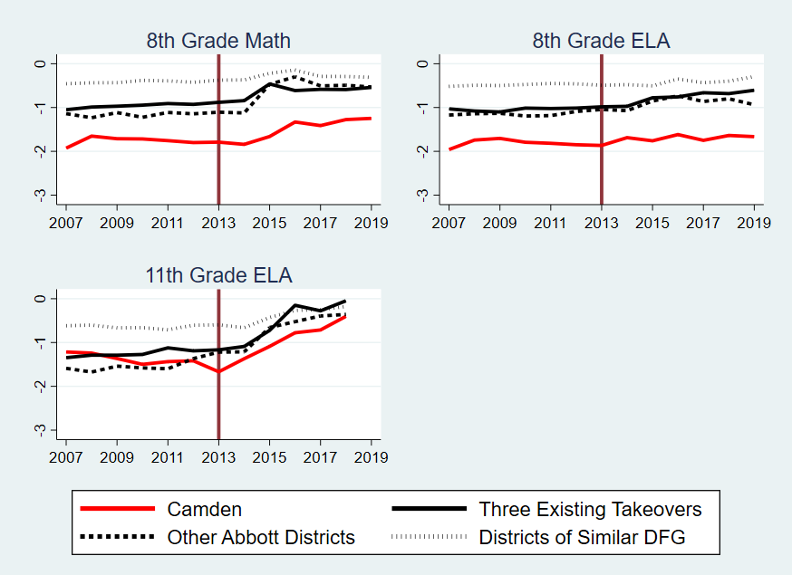

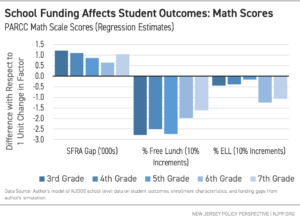

New Jersey saw its largest gains in student achievement for economically disadvantaged students during the mid-2000s – the same time when funding to Abbott school districts was being scaled up. After the Great Recession, however, the state pulled back from its commitment to equitable education funding; consequently, gains for disadvantaged students stalled. In addition, student “growth” is lower, year-after-year, in districts with funding gaps compared to districts without. In recent years, schools in districts with larger funding gaps have lower student outcomes on statewide standardized tests, demonstrating just how important adequate school spending is.

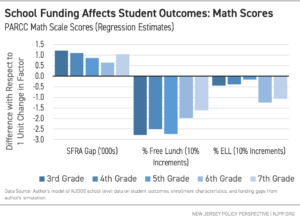

The Governor’s budget for this year – released before the pandemic – was moving more state aid toward traditionally underfunded districts, although not enough to make up for historical funding gaps.[13] In addition, SFRA spending targets were set based on older and lower standards for student learning; they are likely to be insufficient for the state’s newer, more rigorous standards. Closing these spending gaps must be a priority for New Jersey, even in the face of another recession. Our statistical models suggest that closing the SFRA funding gap leads to substantial gains in student outcomes. Closing a spending gap by $1,000, for example, is able to offset about half the difference in math achievement associated with a 10 percentage point increase in a district’s share of low-income students.

In the face of the coming economic downturn, New Jersey should maintain and enhance the features of its school aid system that promote school funding progressiveness while decreasing tax regressiveness. New Jersey’s school funding system has features that drive aid to districts that are already overfunded and have high local taxing capacity. Some state aid for special education, for example, automatically goes to more affluent districts, regardless of those districts’ ability to raise local revenues for schools. If cuts in state aid need to be made this year, New Jersey should first target the aid flowing to these high-capacity districts, including categorical aid that is allocated outside of the adequacy formula.

If further cuts need to be made, it is better to make cuts based on school budgets, and not simply cut overall state aid. Cutting school budgets will still harm the highest-poverty districts, but less than cutting state aid. Judicial actions are not enough to ensure all of New Jersey’s students receive adequate funding: the state must take legislative and administrative actions to resolve the underfunding of many of its school districts, particularly those that do not have standing under the Abbott rulings. In addition, SFRA spending targets should be recalibrated to align with new, higher standards; currently, they are too low, as they were based on previous, less rigorous outcome goals.

Cutting State Aid to Schools Is Always Harmful – But There Are Less Harmful Ways To Cut

| Scenario |

Poverty Quintile |

Local per Pupil

|

State per Pupil |

Cut per Pupil |

Total per Pupil After Cut |

| Baseline |

1-Lowest |

$9,020 |

$1,942 |

|

$10,962 |

| 2-Low |

$8,375 |

$2,372 |

|

$10,746 |

| 3-Middle |

$7,512 |

$2,953 |

|

$10,466 |

| 4-High |

$6,161 |

$3,935 |

|

$10,096 |

| 5-Highest |

$2,623 |

$8,166 |

|

$10,789 |

| Cut 12 percent of State Aid

More harmful to high-poverty

school districts. |

1-Lowest |

$9,020 |

$1,709 |

$233 |

$10,729 |

| 2-Low |

$8,375 |

$2,087 |

$285 |

$10,461 |

| 3-Middle |

$7,512 |

$2,599 |

$354 |

$10,111 |

| 4-High |

$6,161 |

$3,463 |

$472 |

$9,624 |

| 5-Highest |

$2,623 |

$7,186 |

$980 |

$9,809 |

| Cut 5 percent of Per Pupil Revenue

Less harmful to high-poverty

school districts. |

1-Lowest |

$9,020 |

$1,393 |

$548 |

$10,414 |

| 2-Low |

$8,375 |

$1,834 |

$537 |

$10,209 |

| 3-Middle |

$7,512 |

$2,430 |

$523 |

$9,943 |

| 4-High |

$6,161 |

$3,430 |

$505 |

$9,591 |

| 5-Highest |

$2,623 |

$7,626 |

$539 |

$10,250 |

Part 4: The Cost of an Adequate Education In New Jersey

This report turns the focus to adequacy: whether schools have the resources they need to meet a common educational goal. To evaluate New Jersey’s adequacy in school funding, we use the National Education Cost Model (NECM), a method that takes into account both school inputs (spending) and outputs (test scores) to determine whether districts and states are spending what they need to provide students with a quality education.

Our analysis shows New Jersey spends more than other states on its schools; consequently, New Jersey’s educational outcomes are better than those in other states. Yet there are some districts in New Jersey, serving proportionally more students in economic disadvantage, that do not spend enough to meet the modest goal of national average outcomes. These under-spending school districts have higher concentrations of Black and Latinx students, and fewer teachers per 100 students, than other districts that spend adequately. Many of these districts were not Abbott districts: they did not have standing under the earlier Abbott rulings and subsequently did not receive the benefits of increased spending during the pre-SFRA period.

Coupled with the analysis in Part III of this series, there is adequate evidence to show that even as New Jersey is relatively high spending and high achieving state, it has many districts that still do not have enough funding to achieve average educational outcome goals. New Jersey must acknowledge this limitation and fix its state aid formula so districts can meet the challenge of providing an adequate education for all students – even in the face of the post-pandemic fiscal crisis.

Some New Jersey school districts are particularly underfunded by multiple measures.

| District |

SFRA Adequacy Budget (Incl. Spec Ed) |

NJDOE Adequacy Budget |

NJDOE Gap per Pupil |

SFRA Simulated Gap per Pupil |

NECM Gap per Pupil |

| EAST NEWARK BORO |

$22,464 |

$20,417 |

-$9,327 |

-$11,374 |

-$11,639 |

| DOVER TOWN |

$21,346 |

$19,893 |

-$8,586 |

-$10,039 |

-$1,600 |

| FAIRVIEW BORO |

$20,030 |

$18,821 |

-$8,746 |

-$9,955 |

-$7,687 |

| GUTTENBERG TOWN |

$21,573 |

$19,876 |

-$7,965 |

-$9,662 |

-$6,250 |

| BOUND BROOK BORO |

$21,473 |

$20,234 |

-$8,123 |

-$9,362 |

-$1,050 |

| FREEHOLD BORO |

$20,112 |

$18,812 |

-$6,565 |

-$7,865 |

-$5,938 |

| PROSPECT PARK BORO |

$19,155 |

$17,907 |

-$6,372 |

-$7,620 |

-$4,930 |

| BELLEVILLE TOWN |

$20,151 |

$18,167 |

-$5,615 |

-$7,599 |

n/a |

| LINDENWOLD BORO |

$20,545 |

$19,282 |

-$6,101 |

-$7,364 |

-$1,541 |

| CARTERET BORO |

$20,569 |

$18,733 |

-$5,406 |

-$7,242 |

n/a |

| WEST NEW YORK TOWN |

$21,821 |

$20,340 |

-$5,686 |

-$7,167 |

-$6,059 |

Part 5: Inequities Within School Districts

State school funding systems like New Jersey’s focus on allocating resources between districts. There has, however, been increasing federal focus on within-district funding inequities – differences in resources between schools within the same district. For a state like New Jersey, this is a secondary concern: most districts in the state are not large enough to have schools with significant differences in students or resources. In addition, the differences in resources that do exist within districts are often driven by variations in grade levels or special education populations. Attempts to measure within-district inequities in school funding must account for these differences.

Nevertheless, within-district inequities are a valid concern, and federal law requires New Jersey to collect data and conduct analyses. This report suggests methods for conducting these analyses: specifically, school disparity analysis should explore how resources differ between schools based on factors such as student disadvantage, English Language Learner (ELL) status, grade level, special education status, and school type (district, magnet, charter, etc.). The state should conduct these analyses, not local districts, as the state is more likely to develop the data gathering and analysis capacities needed. The methods we describe in this report will provide reasonable, actionable information for schools to more equitably allocate resources.

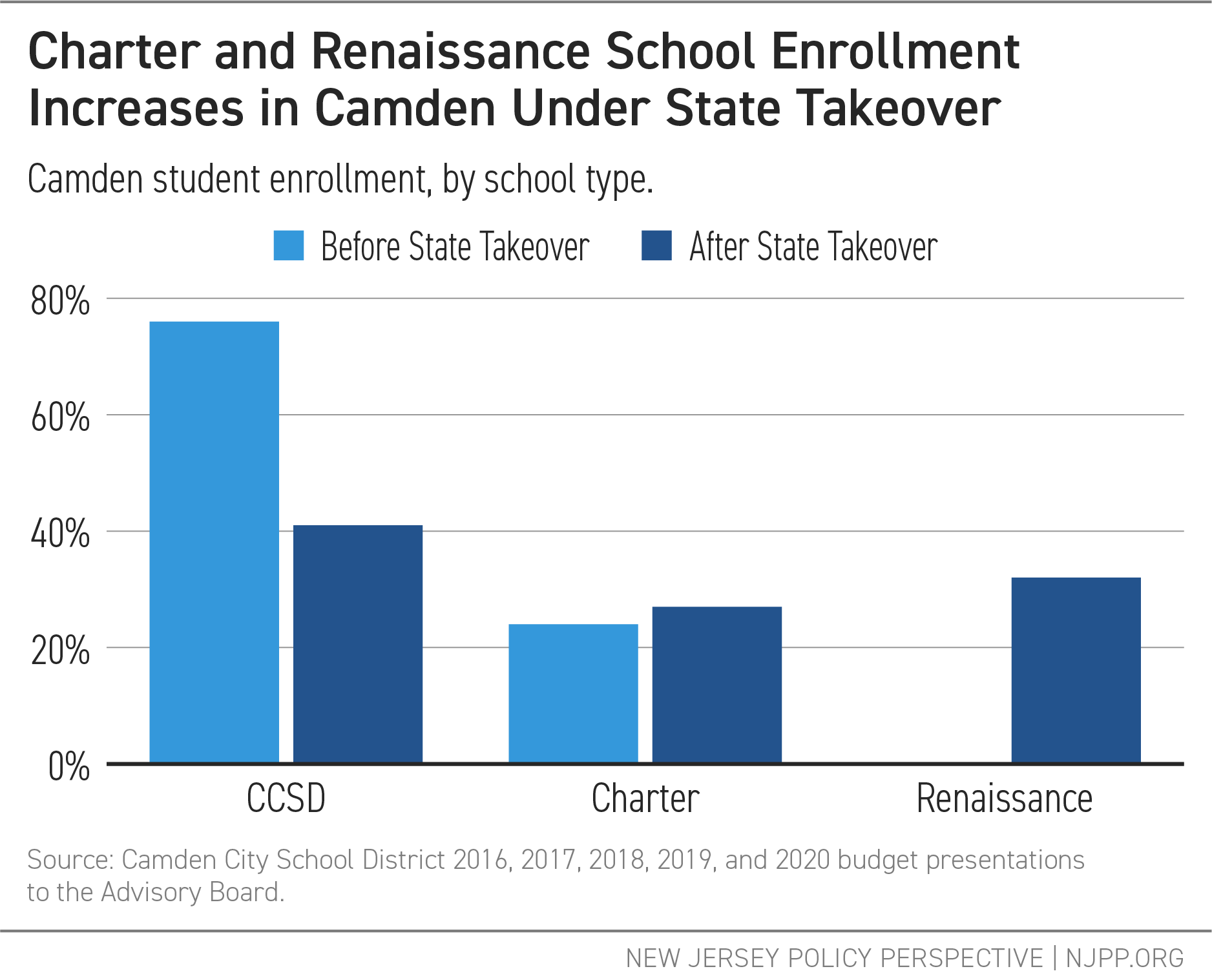

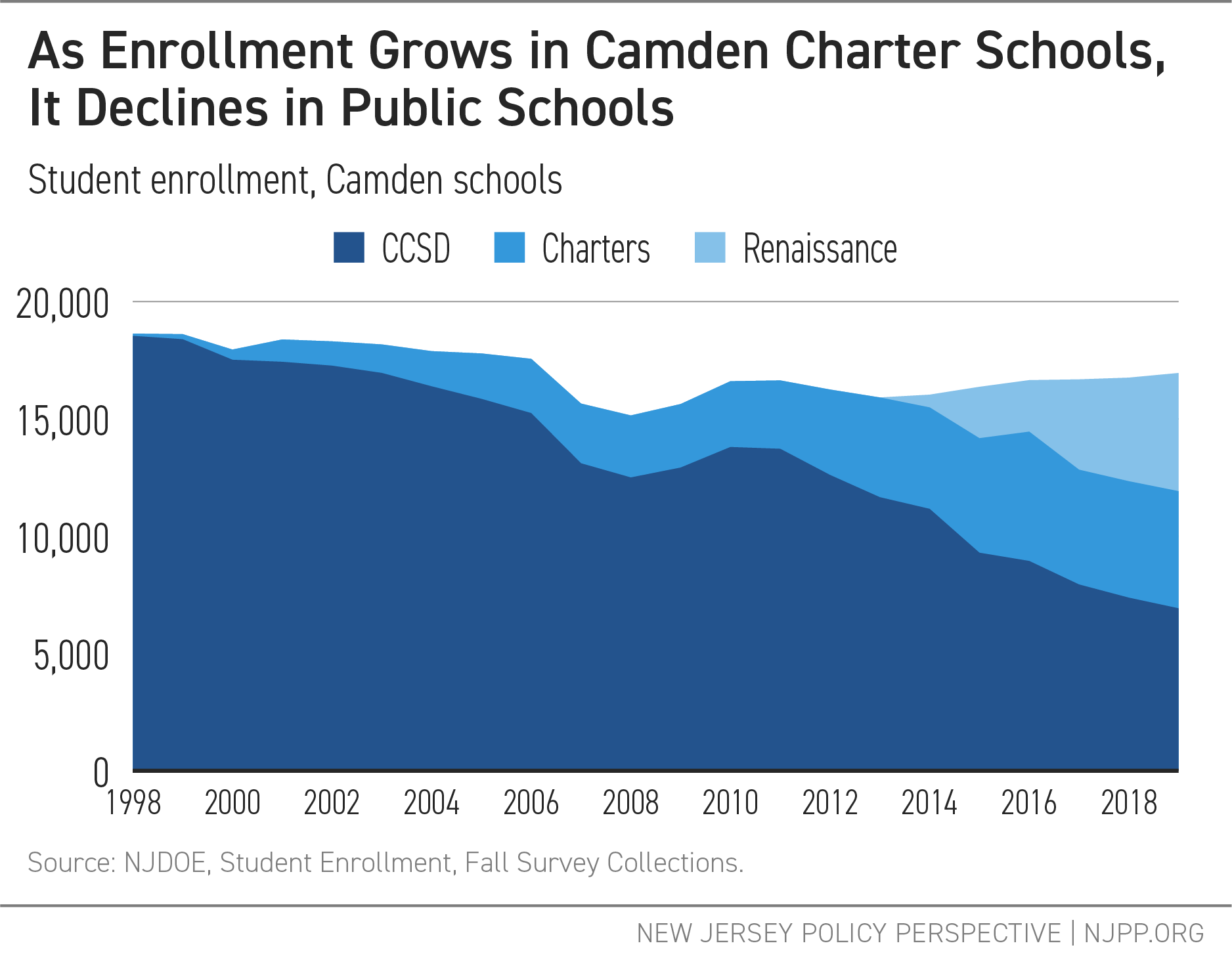

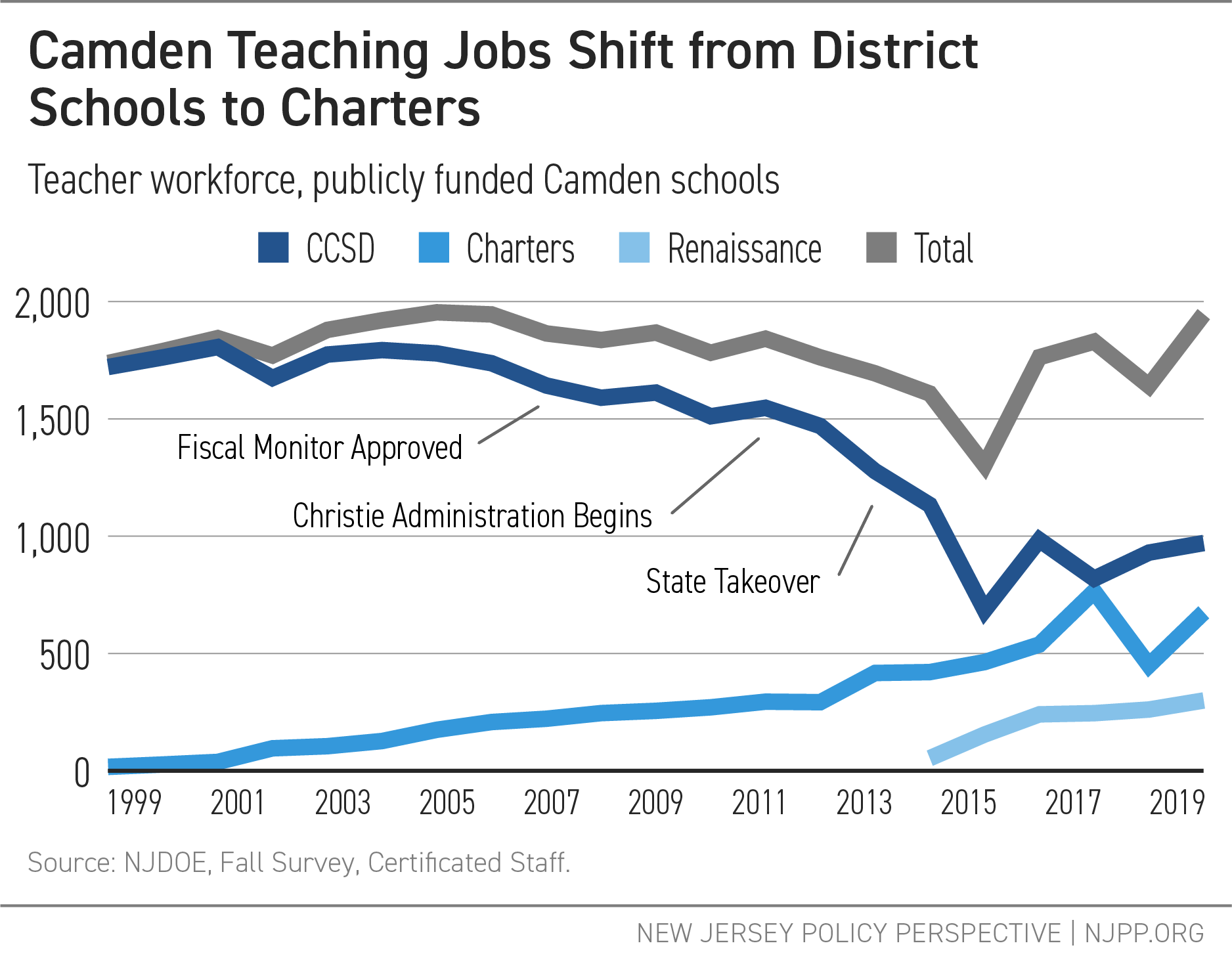

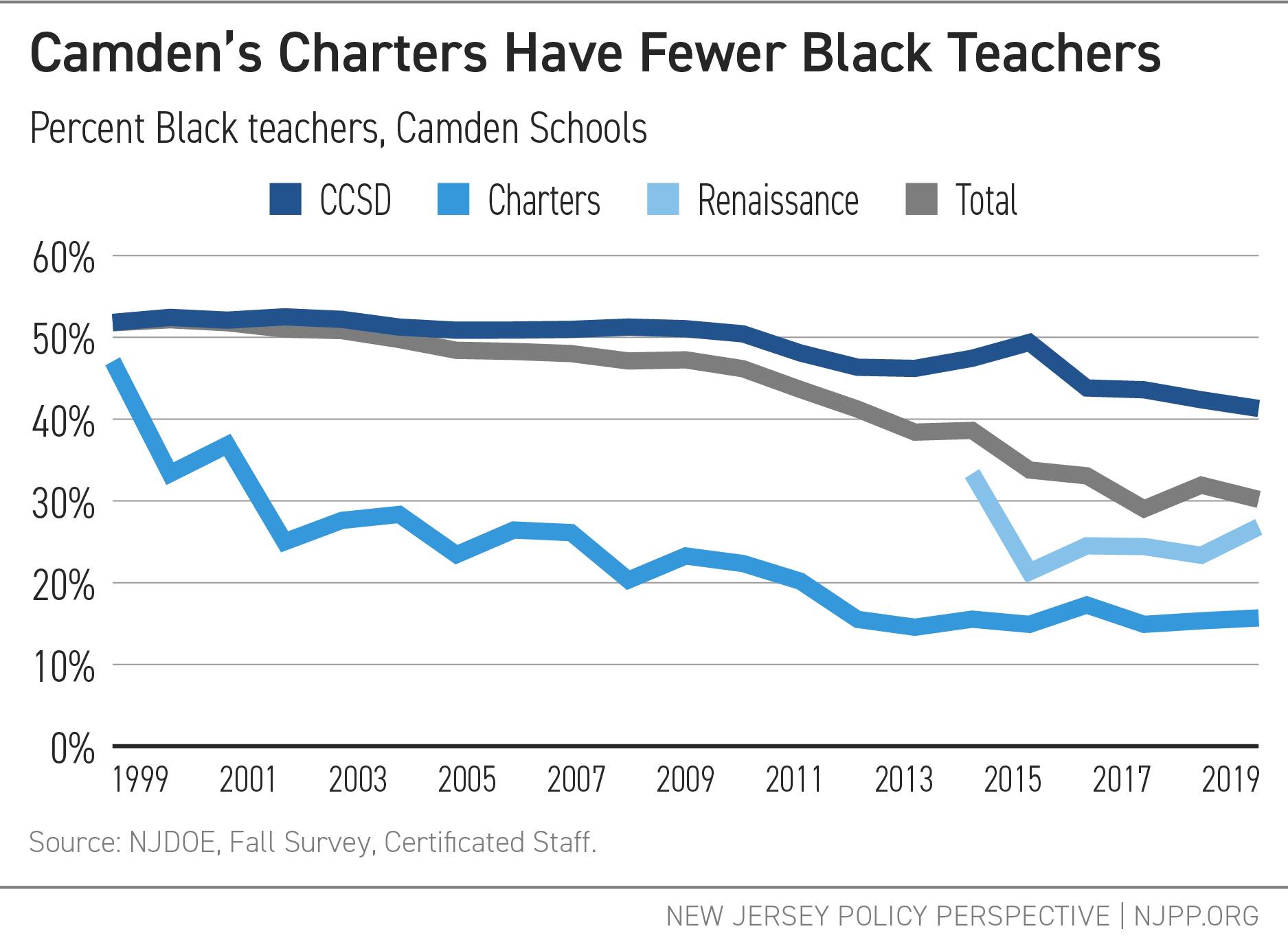

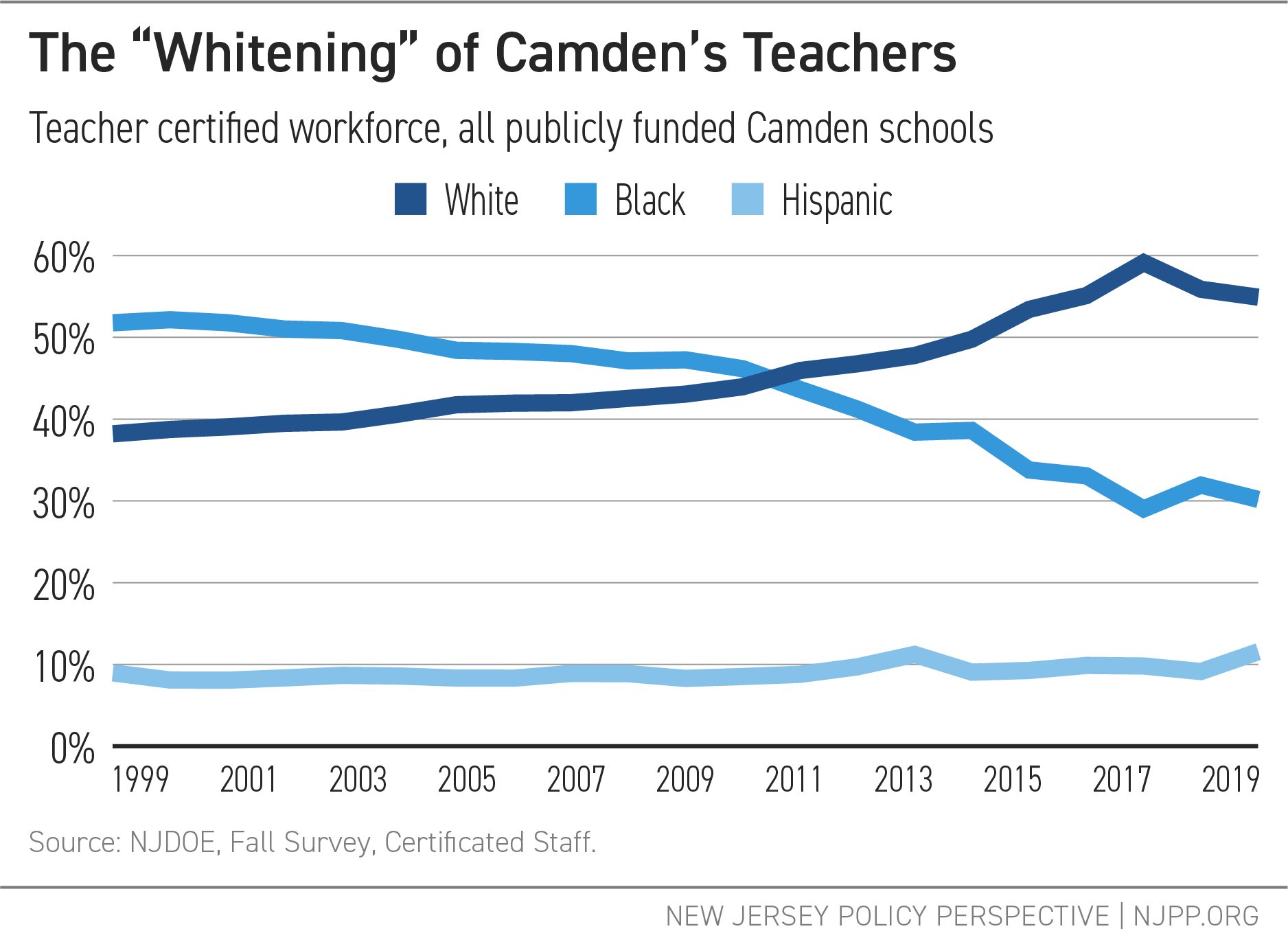

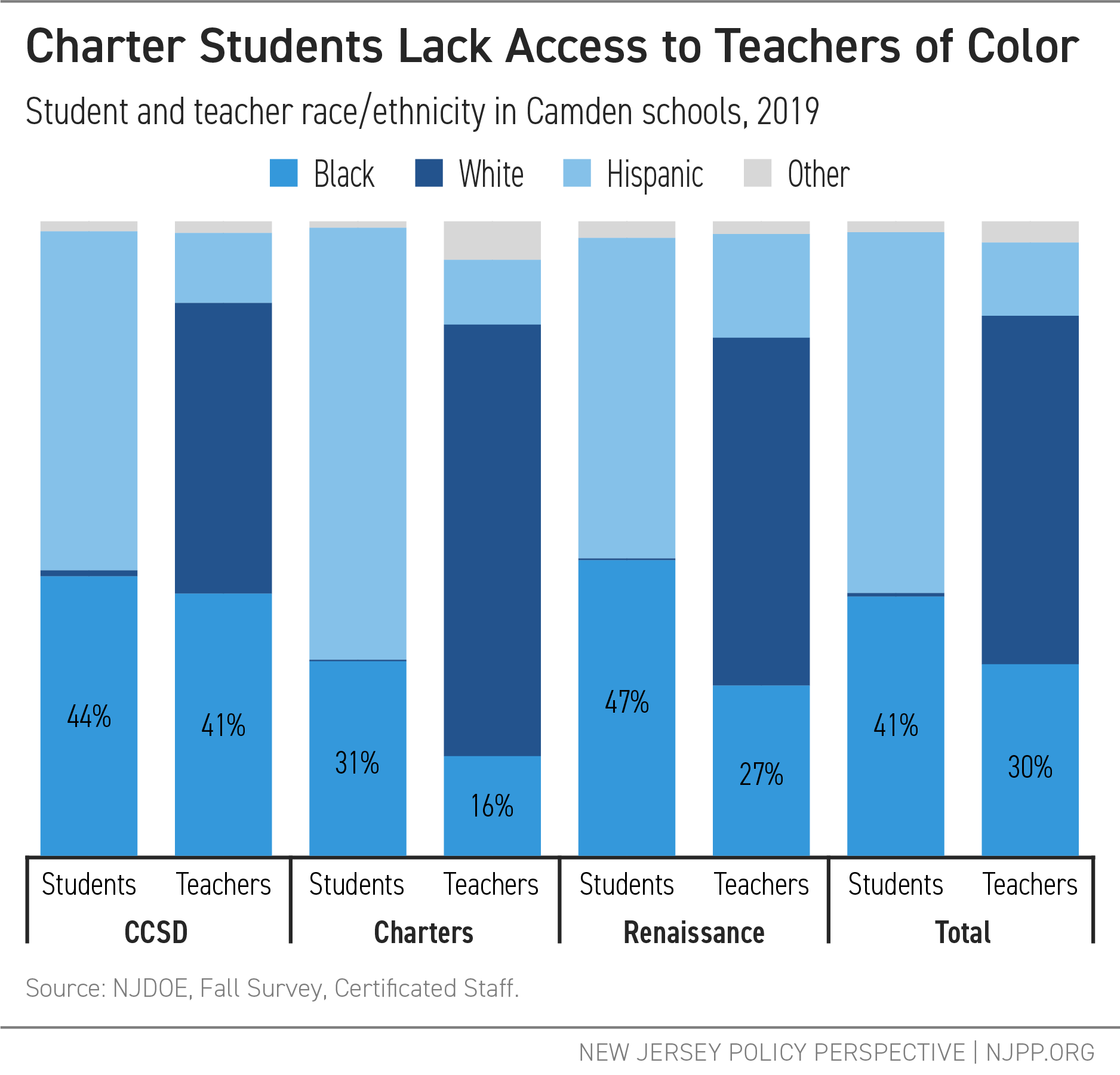

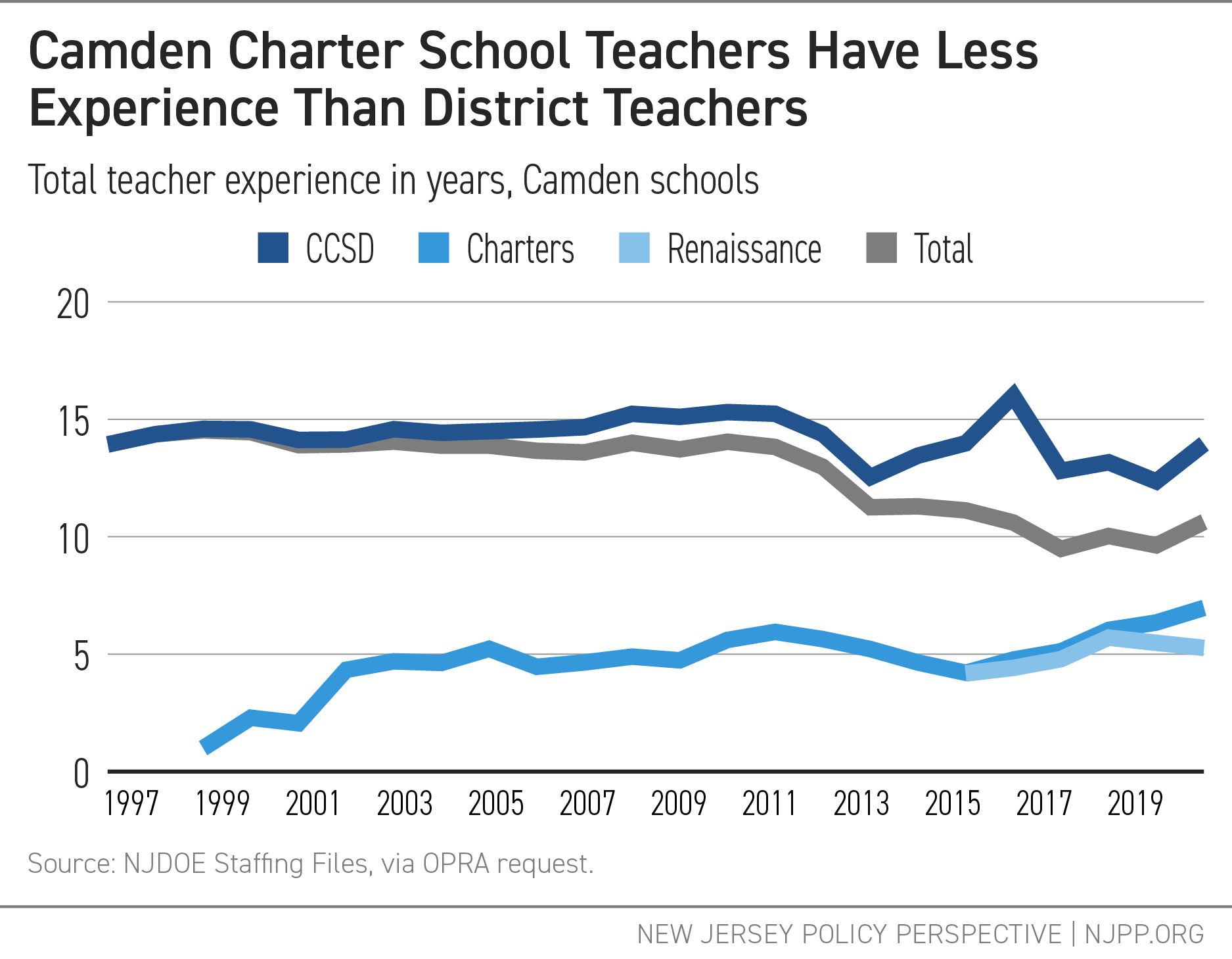

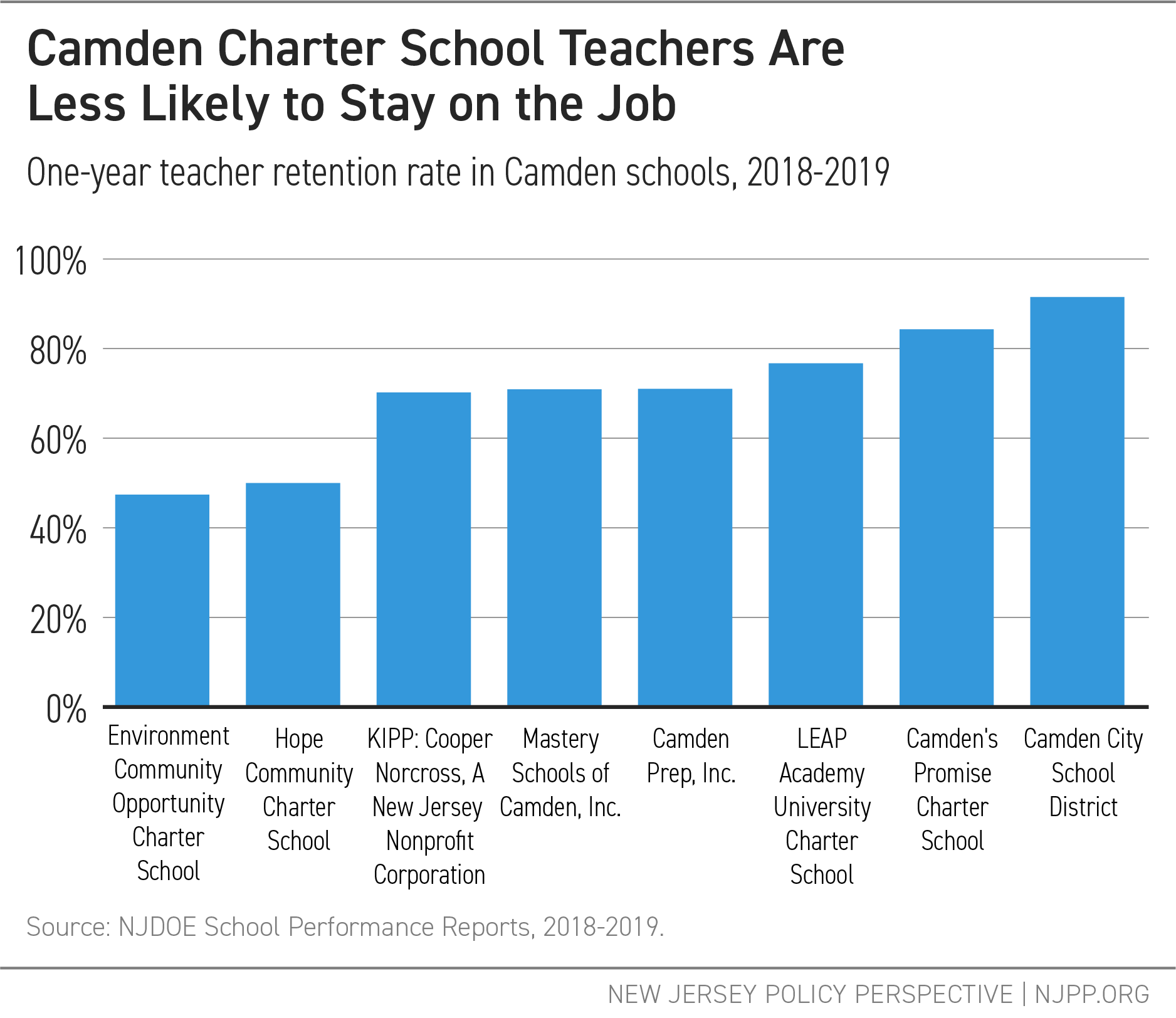

This report also notes that, despite evidence that school districts with lower enrollments and smaller schools are less efficient than larger ones (up to a point), New Jersey has expanded its number of small districts and schools, largely by expanding the number of autonomously operated charter schools. In a time of looming financial crisis, the state should assess whether expanding the number of small schools is fiscally prudent

A Plan for School Funding in New Jersey During and After the Pandemic

Now more than ever, equitable and adequate school funding is critically important for New Jersey’s future. Well-funded schools have always led to better student outcomes, greater individual opportunities, and a stronger economy. But in the days ahead, adequate funding will also be necessary to keep New Jersey’s students healthy and fully engaged in learning – even if students attend school virtually. As difficult as it may be, the state should set its sights on the future – a future that will only be bright if it includes a well-educated citizenry. This means ensuring that schools have the resources they need to address students’ learning needs and keep them safe.

We hope that New Jersey’s K-12 education policymakers and stakeholders find the analysis and recommendations in this series of reports useful as they prepare for the days ahead. Based on our findings, what follows is a plan for school funding during and after the current pandemic.

1. Press for federal relief

As the authors of this series have noted elsewhere: Only the federal government has the ability to tax or borrow on the scale required to cover the states’ ongoing expenses in education, healthcare, and other sectors.[14] Earlier this year, Bruce Baker and Matthew Di Carlo presented a plan for federal intervention to stabilize revenues for public elementary and secondary schools.[15]The plan allocates revenues to states in two phases: first, a major aid package, distributed over two years, to offset the initial shock to state revenue systems; second, a gradual, three-year process of reducing federal aid back to pre-pandemic levels. This plan would help states like New Jersey avoid adopting austerity measures that would harm public schools and the students they serve. Obviously, New Jersey has limited power over federal policy. All of the state’s education stakeholders, however, should agree to work in concert to press for federal aid for schools along with the other states, which face a similar fiscal crisis.

2. Prepare to spend more on schools to keep them safe and healthy.

The health and safety of all children must be a top priority for state and local government. Until the pandemic can be stopped, schools must prepare for a new way of teaching students. Social distancing (requiring smaller class sizes), enhanced maintenance, more health and nursing services, greater access to technology and broadband: this is the new reality of public schooling in New Jersey. The costs must be accounted for when making decisions about the allocation of state aid to schools.

3. Maintain school funding progressiveness

In the face of the coming economic downturn, New Jersey should maintain and enhance the features of its school aid system that promote school funding progressiveness while decreasing tax regressiveness. The School Funding Reform Act (SFRA), as originally designed, drives state aid to districts serving the neediest students, which also happen to be the districts with the least ability to raise their own revenues locally. This should be the ongoing and sustained direction of SFRA: putting money where it is needed most. The state should not, therefore, change the features of SFRA that make it progressive, such as reducing student weights for low-income or English Language Learner status.

4. Put tax increases on the table

Too often, lawmakers automatically rule out any tax increase during an economic downturn (or, for that matter, during a period of growth). But overall state and local taxes in New Jersey are regressive: the state’s wealthiest residents pay less as a percentage of their income than taxpayers in the middle quintile. Asking the most affluent residents of New Jersey to pay at least as much as the average resident so schools can function during and after a pandemic is a reasonable request and sound policy.

5. Keep property taxes, but consider reforms

Complaints about property taxes are a perennial feature of New Jersey politics – and many of those complaints are valid. Yet despite the aforementioned problems associated with property taxes, they have the one important virtue of being much less volatile than income or sales taxes. Keeping them a part of the school funding mix, therefore, helps districts when budgeting for the future. Creative reforms to property taxation, such as such as pooling commercial and industrial property taxes and redistributing them statewide, may mitigate tax and revenue inequities and regressiveness for local residential property owners; policymakers should consider such reforms.

6. If the state must make cuts in school aid, first target the aid going to high-capacity districts

SFRA has features that allocate state aid to school districts that already have the capacity to raise adequate funds locally. Some special education aid, for example, flows to districts that could raise needed revenues on their own. Other “categorical” aid goes to higher-wealth districts, regardless of their capacity to raise taxes. This aid is the result of political compromises; however, in a crisis, those compromises become a luxury the state cannot afford. While cutting school aid is never desirable, New Jersey should first target aid going to these “zero-aid” districts.

7. It is better to cut school district budgets than cut school district aid

In the last recession, New Jersey, unlike other states, chose to make cuts in state aid to districts based on a percentage of their budgets, and not on a percentage of state aid they received. While the cuts were harmful, these were “better” cuts: they harmed the districts enrolling the most disadvantaged students less than they could have. If the state must cut aid, it should once again base those cuts on budgets. An even better approach would be to start by only cutting and/or reallocating state aid presently allocated to districts whose spending exceeds their formula adequacy targets.

8. Recalibrate SFRA to new, higher learning standards

SFRA’s original spending targets were set based on old, outdated outcome goals. Schools are now expected to teach to new, more rigorous standards, while students take ambitious tests aligned to these standards. SFRA’s spending targets should be recalibrated to align with these new goals: if schools are expected to adhere to higher standards, they need more resources. It may also be valuable to consider, at this juncture, the role of health and counseling services in schools, and recalibrating state support for these purposes.

9. Do not wait for judicial actions to equalize school funding

Judicial actions are not enough to ensure all of New Jersey’s students receive adequate funding: the state must take legislative and administrative action. Too many districts that do not have standing under the Abbott rulings have been harmed by the underfunding of SFRA. Many of these districts have large populations of Latinx, English language learners, and low-income students – the very students who need more resources to equalize educational opportunity. Education stakeholders should not expect the courts to solve this problem; the legislative and executive branches must, instead, be proactive and ensure that all of New Jersey’s children have access to well-funded schools.

10. Reconsider the increase of small, autonomous school districts

Research shows that very small schools and school districts are needlessly inefficient. In New Jersey, many are also needlessly racially segregated. Yet New Jersey has allowed the growth of these autonomous entities (some of which are charter schools) over the past decade. Some of these districts also exacerbate racial and economic segregation and isolation. In a time of economic crisis, the state should reconsider whether it can afford more small, autonomous school districts.

11. The State should conduct within-district funding equity analyses

The state should conduct analyses of within-district spending differences, not local districts. These analyses should take into account drivers of cost differences such as special education, student characteristics, grade levels, and school type (magnet, charter, etc.). The methods described in this report will provide reasonable, actionable information for schools to more equitably allocate resources.

12. School funding policies must ameliorate, not perpetuate, systemic racism

The analyses in this series of reports repeatedly show that the greatest harms from school underfunding are felt by New Jersey’s students of color, particularly Latinx and black students. For years, the state has refused to provide the necessary funding these students need to equalize educational opportunity. This must not stand. While education, by itself, cannot negate centuries of racism and oppression, it remains a necessary part of any broad program of social and racial justice. Even a severe economic downturn cannot be used an excuse to continue to underfund schools serving students of color; doing so will only continue to perpetuate the systemic racism that has oppressed these students for far too long.

Endnotes

[1] Baker, B. D. (2017). How Money Matters for Schools. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/how-money-matters-report

[2] Jackson, C. K. (2018). Does school spending matter? The new literature on an old question (No. w25368). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[3] Shores, K., & Steinberg, M. (2017). The impact of the Great Recession on student achievement: Evidence from population data. Available at SSRN 3026151.

Jackson, C. K., Wigger, C., & Xiong, H. (2018). Do school spending cuts matter? Evidence from the Great Recession (No. w24203). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[4] Baker, B. D., & Weber, M. (2019). New Jersey’s School Funding Reform Act at 10 Years. New Jersey Policy Perspective.https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-school-funding-reform-act-at-10-years

[5] Which include using a competitive wage adjustment in place of a CPI to address inflation, and also to capture regional variation in wages at the labor market, rather than at the county level.

[6] The Almanac of Higher Education, 2018-19. Washington, D.C.: The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/almanac-2018

[7] Bruce D. Baker, Mark Weber, and Drew Atchison (June 1, 2020). Weathering the storm: School funding in the COVID-19 era. Phi Delta Kappan. https://kappanonline.org/school-funding-covid-19-baker-weber-atchison/

[8] US Census Bureau Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances, 1977-2017 (compiled by the Urban Institute via State and Local Finance Data: Exploring the Census of Governments; accessed 23-Jun-2020 02:26), https://state-local-finance-data.taxpolicycenter.org

[9] New Jersey lawmakers recently reached a deal to increase taxes on the state’s wealthiest residents. See: Tully, T. (September 17, 2020). “Deal Reached in N.J. for ‘Millionaires Tax’ to Address Fiscal Crisis” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/17/nyregion/nj-millionaires-tax.html

[10] Rumberger, R. W., & Gándara, P. (2015). Resource Needs for Educating Linguistic Minority Students. In Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy (Second Ed.), pp. 585–606. New York: Rutledge.

[11] Sugarman, J. (2016). Funding an Equitable Education for English Learners in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/funding-equitable-education-english-learners-united-states

[12] Baker, B. D. (2016). Does Money Matter in Education? Second Edition. The Shanker Institute.http://www.shankerinstitute.org/resource/does-money-matter-second-edition

[13] See Part 3 of this series for details.

[14] Bruce D. Baker, Mark Weber, and Drew Atchison (June 1, 2020). Weathering the storm: School funding in the COVID-19 era. Phi Delta Kappan. https://kappanonline.org/school-funding-covid-19-baker-weber-atchison/

[15] Bruce D. Baker and Matthew Di Carlo (April, 2020). The Coronavirus Pandemic and K-12 Education Funding. Washington, D.C.: The Shanker Institute .https://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/coronavirusK12final.pdf