The wellbeing of New Jersey’s children and working parents — as well as the state’s recovery from COVID-19 — depends on families being able to balance work and caregiving. Even before the onset of pandemic, many New Jersey families struggled with this balancing act. Now, the current crisis has created untenable conditions for many families who face the additional pressures of unstable and unpredictable employment, schooling, and childcare.

Although lawmakers enacted several state and federal policies to support working families during the pandemic, many of these programs are neither universal nor permanent. As a result of underinvestment and piecemeal policymaking, many workers continue to face barriers to paid leave, job protections, adequate wages, quality and affordable childcare, and work stability and flexibility. This report examines the circumstances of New Jersey’s working parents, assesses the strengths and shortcomings of existing policies, and identifies solutions to improve conditions for parents, children, and employers.

Households with Children Face Disproportionate Barriers to Economic Security

New Jersey families with children faced disproportionately large economic challenges both before and during COVID-19, including poverty and the loss of employment and income. Prior to the pandemic, families with children under 18 were already more likely to live below the federal poverty level than families without children.[i] In 2019, approximately one in ten families with children in New Jersey lived in poverty.[ii] Now, almost a year into the pandemic, working families are falling further behind. Households with children are twice as likely (19 percent) to report that it was very difficult to cover usual expenses during the last seven days as households without children (9 percent), according to the most recent U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey (conducted between November 11 -23, 2020).[iii] In addition, while COVID-19 has caused unprecedented economic disruptions across the state, households with children in New Jersey were 23 percent more likely to report experiencing loss of employment income since the beginning of the state’s stay-at-home order in mid-March than families without children.[iv]

Low-Income, Black, and Latinx Workers are Least Likely to Work from Home

The ability to work from home has enabled many parents to practice social distancing while continuing to work during the pandemic. Not all employees, however, are able to telework. One key factor that influences whether an employee is able to work from home is occupational segregation. Because employment opportunities are shaped by systemic barriers to education and discrimination in hiring and promotion, ability to work from home varies by race and income.

Prior to the onset of COVID-19, only one in three workers was able to work from home. While approximately one in three Asian and white workers were able to telework, only one in five black workers and one in six Latinx workers were able to telework. In addition, high wage workers were six times as likely to be able to work from home as low wage workers.[v]

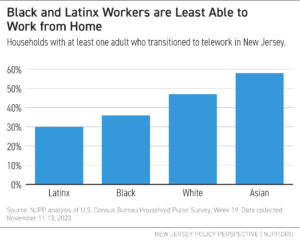

Racial and income disparities in teleworking that existed prior to the onset of the pandemic have been compounded during the current crisis, according to a survey that asked if any adults in a household substituted any work that was typically conducted in person with telework since mid-March. While over half (58 percent) of Asian respondents and nearly half (47 percent) of white respondents substituted some or all of their typical in-person work with telework, only one-third of Black (36 percent) and Latinx (30 percent) respondents transitioned to telework.[vi]

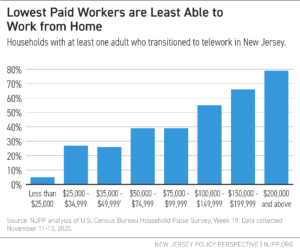

The ability to work from the safety of home during COVID-19 is most often afforded to workers who are the highest paid.[vii] At least one adult was able to transition to remote work during the pandemic in 79 percent of households earning over $200,000 per year and in 55 percent of households earning between $100,000 to $149,999 per year. In general, households with the lowest incomes are least likely to have transitioned to some or all telework due to COVID-19. Fewer than a quarter of households earning less than $50,000 per year had at least one adult who moved some or all their work to telework due to the pandemic. Accordingly, the households least able to bear the additional costs of childcare resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic are often those who need it most.

COVID-19 Intensifies Childcare Challenges

While the inadequacies and inequities in New Jersey’s childcare infrastructure did not begin with the COVID-19 pandemic, the current crisis has exacerbated and complicated childcare challenges. Approximately one-third (266) of New Jersey’s school districts began the 2020 school year with plans for all remote-learning, approximately half (395) had plans for hybrid models, and less than 10 percent (75) had plans for in-person learning.[viii] In addition, families have had to navigate diverse and changing conditions among childcare providers and schools in New Jersey. Because of the constantly evolving nature of the ongoing public health emergency, facility closures often come with little or no advanced notice, leaving families scrambling to plan childcare. Even among parents who can telework, many now face the dual responsibility of working while providing childcare or overseeing remote learning due to a loss of childcare or shift to online learning. For families with children that require ongoing supervision, juggling work and childcare duties simultaneously is an impossible task.

Before the onset of COVID-19, childcare was already a challenge for many working families. Most children (73 percent) in New Jersey live in households where all parents work.[ix] For single parents, the majority of whom are women, the difficulties of managing childcare and work are especially acute. The vast majority of single parents work – 90 percent of single fathers and 84 percent of single mothers.[x]

New Jersey is home to nearly 600,000 young children and infants, as well as 1.3 million school aged children and teens (between the ages of 6 and 17).[xi] In 2019, almost half (46 percent) of children under the age of six in New Jersey lived in a childcare desert, or a place where the number of children is more than three times the licensed childcare capacity.[xii] In addition to inadequate and inequitable childcare availability, childcare is not affordable for many low- and moderate-income families. New Jersey ranks as the fifteenth most expensive state in the country for childcare costs. The average cost for one year of care for a four-year-old in New Jersey is $10,855. Infant care is even more costly for New Jersey’s families, with an average annual cost of $12,988 per year.[xiii]

Insufficient affordable and quality childcare not only harms children, but also pushes parents – especially mothers – out of the workforce. Accordingly, lack of access to childcare is not only a problem for families with children, as it also hurts employers and New Jersey’s broader economy. Over 300,000 adults in New Jersey reported that they could not work because they had to care for children not in school or daycare in November 2020, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.[xiv] Similarly, in a poll of over 900 parents of infants and toddlers in New Jersey, 14 percent of parents reported that they left their jobs to manage childcare and 17 percent reported that they were forced to reduce their work hours.[xv]

Surveys of New Jersey residents suggest that the current crisis has had a particularly large toll on working mothers, low-income parents, and Black and Latinx parents. Among parents of children under the age of three in New Jersey, women (19 percent) were six times more likely to report that they had left their jobs to manage childcare since the onset of COVID-19 than men (three percent).[xvi] In an October 2020 poll of parents with children in New Jersey public schools, low-income Black and Latinx parents were 1.5 times more likely than parents overall to either take time off from work or leave their job to stay at home when their child is not in school (22 percent vs. 14 percent).[xvii]

State lawmakers have taken some steps to improve access to and stabilize childcare during COVID-19, but more must be done. For example, the New Jersey School-Age Tuition Assistance Program provides financial support for care for school-aged children engaged in remote learning due to COVID-19. To participate in this program, families must have a gross household income less than $150,000 per year. In addition, the childcare provider must be licensed or registered, which excludes families who rely on care from a relative.[xviii] While this program has been helpful for many households with school-aged children, it is temporary – the program is scheduled to expire on December 30th, 2020.

As COVID-19 infection rates remain high, uncertainty and fluctuation around school and daycare statuses is likely to continue to pose a significant challenge. [xix] In addition to extending and expanding programs that increase childcare affordability, a greater commitment of public resources is needed to create lasting, meaningful reform in the state’s childcare system to promote childcare availability and quality for all families. With structural improvements and adequate and equitable investments, the state can build a stronger childcare system that better supports the wellbeing of New Jersey’s children and working families as well as the state’s recovery from the current crisis.

Federal Expanded Leave Programs Lack Inclusivity and Longevity

The federal and state governments’ patchwork policy response to the pandemic has partially and temporarily improved conditions for some working parents. However, the gaps in some federal and state policies neglect to fully address the needs of workers and children. Because workers’ ability to take leave to care for a child depends on a variety of factors, including employer type and size, employer’s policies, and whether an employee has already taken leave, many parents remain in the difficult situation of juggling work responsibilities and caring for their children. Further, many of these programs are set to expire at the end of 2020. Amid unprecedented uncertainty around the status of schools and childcare, examining gaps in existing programs and taking steps to ensure universal coverage is more important than ever.

Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)

Enacted in March 2020, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) contains two key provisions for certain employers to provide paid leave to their employees for specified reasons related to COVID-19. The Emergency Paid Sick Leave Act (EPSLA) grants workers access to up to 80 hours (or the equivalent of two weeks of work for part-time workers) of partially paid leave if they are unable to work due to a COVID-19 quarantine order, illness, or their child’s COVID-19 related school / childcare closure.[xx] The Federal Emergency Family and Medical Leave Expansion Act (EFMLEA) provides employees who need to care for a child whose school or daycare is closed due to COVID-19 up to 12 weeks of job-protected partially paid leave .[xxi]

Under both of these provisions of the FFCRA, wage replacement for workers is tied to the reason for taking leave — wage replacement for employees who take leave for childcare is lower than for those who take leave due to their own illness. Employees who are unable to work because they are themselves quarantining or experiencing COVID-19 symptoms may take leave at their regular pay rate (up to a maximum of $511/day). Employees who take Emergency Paid Sick Leave to provide care are eligible for two-thirds of their regular rate of pay (maximum of $200/day). For employees who are taking Emergency Family and Medical Leave (EFML), the first two weeks may be unpaid (these weeks can be combined with other leave such as the EPSLA) and the remaining 10 weeks are paid at two-thirds of the employee’s regular pay rate (maximum of $200/day).[xxii]

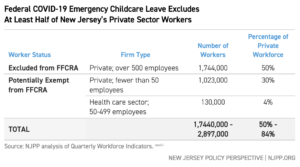

While the leave available under the FFCRA has been helpful for many workers and employers, the program is set to expire on December 31, 2020. Even if the program is extended, not all workers are eligible to take leave under the FFCRA. Workers at large employers (over 500 employees) are excluded from all paid leave provisions under this law. As a result of this exemption, half of New Jersey’s private workforce (1.7 million workers) is automatically excluded from the FFCRA.[xxiii] This exclusion disproportionately limits access to paid leave for Black workers, who are overrepresented among workers at private firms with over 500 employees. While 50 percent of all private sector workers in New Jersey work for firms with over 500 employees, 62 percent of Black workers at private employers work for firms with over 500 employees.[xxiv]

Under the FFCRA, companies with fewer than 50 employees may qualify for exemption from the requirement to provide leave to care for a child out of school or childcare if these requirements would “jeopardize the viability of the business.”[xxv] In addition, employers may exclude healthcare providers and emergency responders from taking paid leave due to school closings or childcare unavailability.[xxvi] As a result of these two exemptions, an additional 34 percent of the private workforce (1.2 million employees) could potentially be denied paid leave for child care. The table below shows the estimated amount of private sector workers in New Jersey who are excluded from coverage under each exemption. In total, only 16% to 50% of New Jersey’s private workforce is guaranteed emergency paid leave for COVID-19 related childcare under the FFCRA.[xxvii] [xxviii]

The FFCRA’s interaction with other programs also poses challenges for many workers. Employees who need to take leave due to both COVID-19 related reasons and other circumstances are not eligible for additional leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). For example, an employee who is a new parent or had to take medical leave may have exhausted their FMLA leave earlier in the year would not be able to access this benefit. Similarly, workers who have taken leave under the FFCRA, but later need take leave because of another illness or caregiving need, do not have access to FMLA for the remainder of the year.

All Workers Deserve Flexibility, Paid Leave, and Protections

The transition to remote learning in New Jersey’s schools and changes to childcare availability due to COVID-19 has complicated the balancing act between work and caregiving for New Jersey’s working families. It is clear that New Jersey cannot wait for the federal government to act — Congress has yet to negotiate an extension of critical leave programs under the FFCRA that expire at the end of December — making it especially important that state lawmakers support the economic security, health, and wellbeing of working families. In a state where the majority of parents are workers, New Jersey cannot afford to push parents out of the workforce. While the challenges facing working parents in New Jersey are substantial, there are several steps that the state can take to immediately improve conditions for working families with children, including increasing flexibility, expanding paid leave, and strengthening protections for workers.

Increase Flexibility and Stability for Workers

The communities that have been hardest hit by COVID-19 are also those that are least likely to be able to work from home, least likely to have stable and predictable schedules, and least likely to be able to afford childcare. In July 2020, state lawmakers introduced legislation that would prohibit employers from requiring employees to be physically present at work during the public health emergency if they can work remotely and have a school-aged child.[xxix] This is an important step and may help many parents who are able to perform their work remotely; however, for many workers, teleworking is not possible.

In addition to risking their health to perform in-person work, many workers in New Jersey continue to face inflexible, unpredictable, and unstable scheduling practices. These scheduling practices pose challenges to meeting and planning caregiving responsibilities.[xxx] Regulating scheduling practices for hourly workers to ensure that workers have advanced notice of their schedules, fair compensation, sustainable hours, and flexibility when they need it, would improve conditions for New Jersey’s working families.

Expand Paid Leave

Gaps in existing policies leave many New Jersey families without paid leave, making them more likely to lose income and face financial insecurity. Expanding access to paid leave during a public health emergency would help keep more New Jerseyans in the workforce and better accommodate the needs of workers who are sick or need to provide care. Given the exclusions in FFCRA and looming sunset date for these federal paid leave provisions, the state cannot afford to rely on the federal government to provide adequate paid leave to workers.

By making minor changes to existing state programs, New Jersey lawmakers can substantially improve access to paid leave, especially for workers caring for children due to school and childcare changes resulting from COVID-19. For example, expanding the state Earned Sick Leave law to provide for additional days and improved access to paid sick days during a public health emergency would allow more workers to be able to care for loved ones, maintain financial security, and remain in the workforce. In addition, New Jersey could expand eligibility for Family Leave Insurance (FLI) to parents who are ineligible for other paid leave programs and who are unable to work because they must care for a child at home due to a COVID-19 related school or daycare closures. This program could also be made more inclusive by expanding eligibility to include all workers who pay into the program, regardless of immigration status.

Strengthen Job Protections

New Jersey has taken several steps to improve access to job protections, yet far too many workers still refrain from taking leave out of fear of losing their job or retaliation from their employer. Near the onset of COVID-19, New Jersey lawmakers enacted legislation to prohibit employers from terminating or penalizing workers who have themselves contracted or are likely to have contracted an infectious disease and request to take time off work based on the recommendation of a licensed medical professional.[xxxi] Nevertheless, this measure does not provide any protection for workers who take leave due to school or childcare closures resulting from COVID-19.

New Jersey’s Family Leave Act (NJFLA) has been expanded to include care for a loved one due to COVID-19 and care for a child at home because of a public health emergency related closure of schools or places of care.[xxxii] Nevertheless, NJFLA remains limited in several ways. Notably, NJFLA does not apply to employers with fewer than 30 employees, and the protections only cover employees who have been at their job for at least one year and have worked 1000 hours. On the other hand, under the FFCRA, there is no required duration of employment as part of the EPSLA provision and for EFMLEA, workers only have to be employed for 30 calendar days. Since both provisions of the FFCRA expire at the end of 2020, state lawmakers can partially address the gap that will be created in the absence of Congressional action by extending NJFLA to workers who have been employed for 30 days (as opposed to one year) when taking leave during a public health emergency.

Parents are Essential Too

During a health and economic crisis that has upended school, childcare, and work arrangements, ensuring that employees can take time off when they are sick or need to care for their loved ones is essential. Access to workplace flexibility, comprehensive paid leave, and job protections are not only important for the wellbeing of families with children, but also for public health and the economy. By making meaningful changes to promote the wellbeing of New Jersey’s workers who have disproportionately borne the harm caused by the current pandemic, New Jersey will not only be able to have a stronger and more equitable recovery from COVID-19, but also be better prepared for future crises.

End Notes

[i] The Census Bureau considers families with a total money income (before taxes) less than the family’s poverty threshold to be in poverty. For example, the 2019 poverty threshold for a family with one adult and one child was $17,622. For a family with two adults and two children, the poverty threshold was $25,962. To access poverty threshold tables, see https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html .

[ii] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2019 1-Year Estimates. Table S1702: Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months of Families. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=poverty%20child&g=0400000US34&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1702&hidePreview=false

[iii] United States Census Bureau. (2020) Household Pulse Survey. Week 19. Spending Table 1: Difficulty Paying Usual Household Expenses in the Last 7 Days, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html

[iv] United States Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey. Week 19. Employment Table 1. Experienced and Expected Loss of Employment Income, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html

[v] Gould, Elise and Hedi Shierholz. 2020. “Not everybody can work from home.” Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/black-and-hispanic-workers-are-much-less-likely-to-be-able-to-work-from-home/

[vi] United States Census Bureau. 2020. Household Pulse Survey: Week 19. Transportation Table 1. Teleworking during the Coronavirus Pandemic, by Select Characteristics: United States. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html

[vii] United States Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey: Week 19. Transportation Table 1: Teleworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Select Characteristics. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html

[viii] Mooney, John and Colleen O’Dea. (September 2020). “NJ Schools Reopen: What Districts Are Remote, In-Person, or Hybrid?” NJ Spotlight News. https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/09/nj-schools-reopen-plan-list/

[ix] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2019: ACS 1-Year Estimates. Table DP03: Selected Economic Characteristics. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=parents%20employment&g=0100000US_0400000US34&tid=ACSDP1Y2019.DP03&hidePreview=false

[x] Due to limitations in the data, gender identities of the total population of parents could not be fully accounted for here. Please note that transgender and gender nonconforming people, among others, are often made invisible by data.

[xi] American Community Survey. 2019 1-Year Estimates. “Age of Own Children Under 18 Years in Families and Subfamilies by Living Arrangement by Employment Status of Parents”. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=employment%20children&g=0100000US_0400000US34&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B23008&hidePreview=true

[xii] Center for American Progress. “Early Learning Factsheet 2019 – New Jersey”. https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2019/09/12071433/New-Jersey.pdf

[xiii] Economic Policy Institute. October 2020. “The cost of childcare in New Jersey”. https://www.epi.org/child-care-costs-in-the-united-states/#/NJ

[xiv] United States Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey: Week 19. Employment Table 3. Educational Attainment for Adults Not Working at Time of Survey, By Main Reason for Not Working and Paycheck Status While Not Working. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html

[xv] Fairleigh Dickinson University. September 30, 2020. “Poll: New Jersey Working Parents Face Child Care Challenges Due to COVID-19” https://view2.fdu.edu/publicmind/2020/200930/index.html

[xvi] Fairleigh Dickinson University. September 30, 2020. “Poll: New Jersey Working Parents Face Child Care Challenges Due to COVID-19” https://view2.fdu.edu/publicmind/2020/200930/index.html

[xvii] Global Strategy Group. November 17, 2020. “Parents’ Survey Identifies Stark Racial and Income Disparities This Fall Semester” https://njchildren.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NJ-Public-School-Parents-Memo-Updated-F11.16.20.pdf

[xviii] New Jersey Department of Human Services. ”COVID-19 Childcare.” https://www.childcarenj.gov/COVID19

[xix] New Jersey Department of Health. 2020. “New Jersey COVID-19 Dashboard.” https://covid19.nj.gov/

[xx] U.S. Department of Labor. (2020) “Temporary Rule: Paid Leave Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act.” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/ffcra

[xxi] U.S. Department of Labor. (2020) “Temporary Rule: Paid Leave Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act.” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/ffcra

[xxii] U.S. Department of Labor (2020). “Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Employee Paid Leave Rights.” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pandemic/ffcra-employee-paid-leave

[xxiii] U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Quarterly Workforce Indicators (1990-2018). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Longitudinal-Employer Household Dynamics Program. https://qwiexplorer.ces.census.gov.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] U.S. Department of Labor. Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Employee Paid Leave Rights. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/pandemic/ffcra-employee-paid-leave

[xxvi] Paid Leave Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. (2020). 85 FR 19326. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/04/06/2020-07237/paid-leave-under-the-families-first-coronavirus-response-act

[xxvii] U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Quarterly Workforce Indicators (1990-2018). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Longitudinal-Employer Household Dynamics Program. at https://qwiexplorer.ces.census.gov. These estimates are based on an average of quarterly data from 2018, which is the latest year for which data are available.

[xxviii] U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Quarterly Workforce Indicators (1990-2018) [computer file]. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, Longitudinal-Employer Household Dynamics Program. https://qwiexplorer.ces.census.gov

[xxix] New Jersey 2019th Legislature. Assembly No. 4462. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2020/Bills/A4500/4462_I1.HTM

[xxx] Schneider, Daniel, Kristen Harknett, and Megan Collins. (2020) Working in the Service Sector in New Jersey. https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/working-in-the-service-sector-in-new-jersey/

[xxxi] New Jersey Public Law 2020, Chapter 9. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2020/Bills/PL20/9_.PDF

[xxxii] New Jersey P.L. 2020, Chapter 23. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2020/Bills/PL20/23_.PDF