To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

Access to safe, accessible, and medically competent reproductive health care in the United States is under concentrated and powerful attack. A more radical Supreme Court now puts in jeopardy key reproductive health services like Title X federal funding for family planning and the constitutional right to abortion. The current political climate provides progressive-leaning states like New Jersey an urgently important opportunity to develop and enact forward-thinking reproductive health care policy.

This report highlights some of those opportunities by examining a wide cross section of gaps and disparities in New Jersey’s reproductive health care landscape. The selected issues include:

- Expanding access to contraception and abortion

- Addressing maternal and infant mortality disparities

- Providing dignity for people who are incarcerated

- Expanding health care for undocumented immigrants

This sampling was chosen due to its urgency, invisibility, and vulnerability to political attacks. By highlighting a cross-section of issues, the report aims to foster renewed interest among policymakers and advocacy organizations in pursuing state-level policy that guarantees every individual—regardless of circumstances or identity—equal access to reproductive health care services.

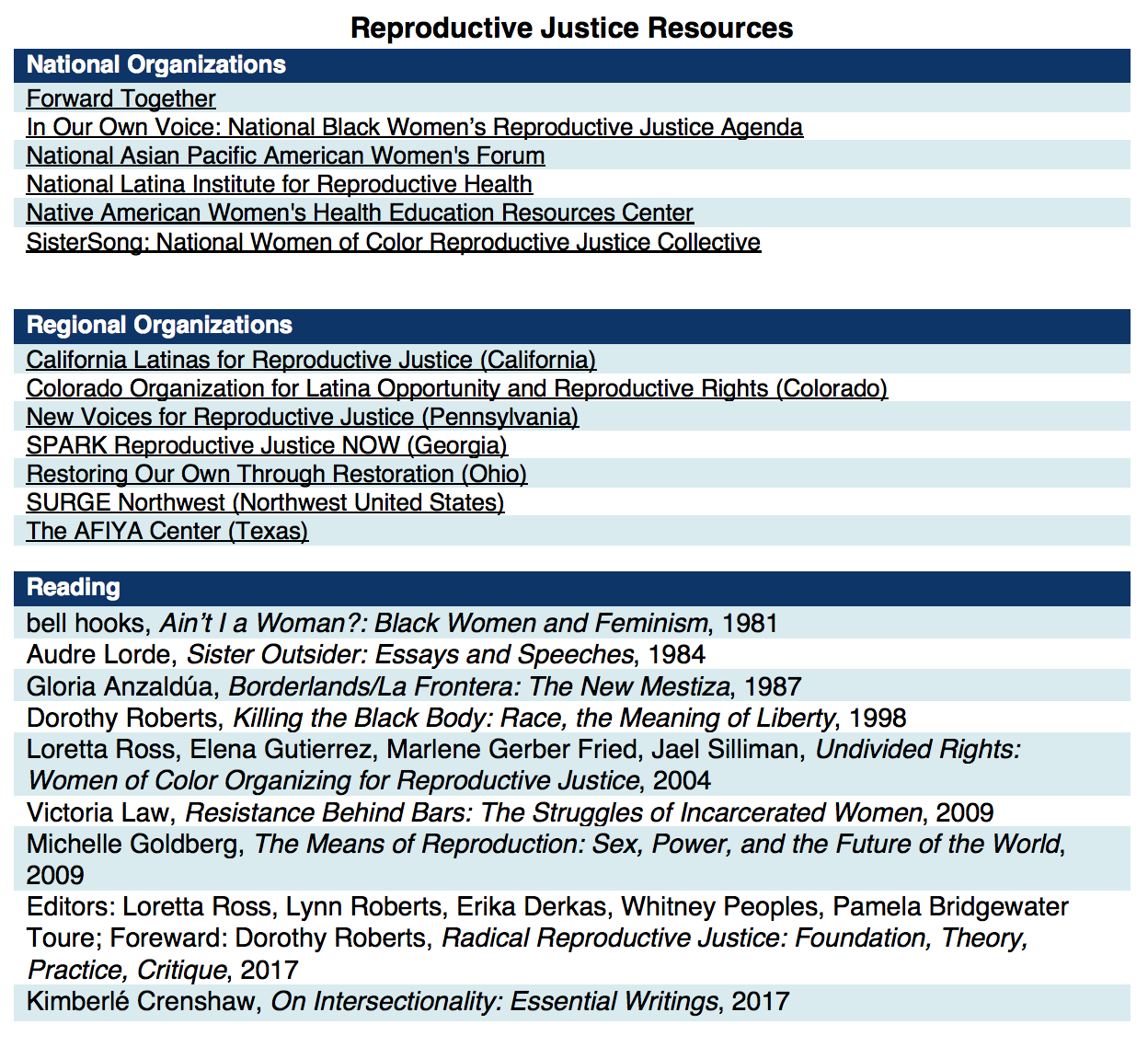

The reproductive health care gaps identified in this report are based on a series of one-on-one interviews conducted with community leaders and advocates from several organizations representing communities that chronically face barriers to reproductive health care (see the list at end of the report). Those facing these challenges due to their circumstance, income, or identity include, but are not limited to, women of color, people who are undocumented, LGBTQI communities, incarcerated people, people with disabilities, indigenous high-poverty communities, young people, and residents of rural areas. As experts of their own lives, community members and leaders from these groups are best equipped to inform policy changes that can improve those lives.

By focusing on those who have been historically underserved, this report follows the example of the groundbreaking work of Reproductive Justice, the movement created by women of color as an alternative to the mainstream reproductive rights framework. To be clear, this report was developed by individuals who are not associated with Reproductive Justice organizations. Rather, the intention is to inspire New Jersey stakeholders to invest in the principles developed by leaders of the Reproductive Justice movement and champion legislation that embodies the Reproductive Justice framework. For more information about the history of the Reproductive Justice movement and framework, see Appendix I.

Reproductive Health Care Policy in the Garden State

New Jersey has a strong record for advancing reproductive health care policy, but programs that serve low-income people, especially women of color, have chronically been vulnerable to funding cuts.[1] For example, $7.5 million in annual state grants for family planning services, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections, and cancer screenings for low-income residents were cut from the state budget for eight consecutive years.[2] Those cuts forced six of the 58 family planning clinics in the Garden State to close. Of the 136,000 mostly low-income patients served by New Jersey’s family planning clinics each year, many were left to find care elsewhere or skip care altogether.[3]

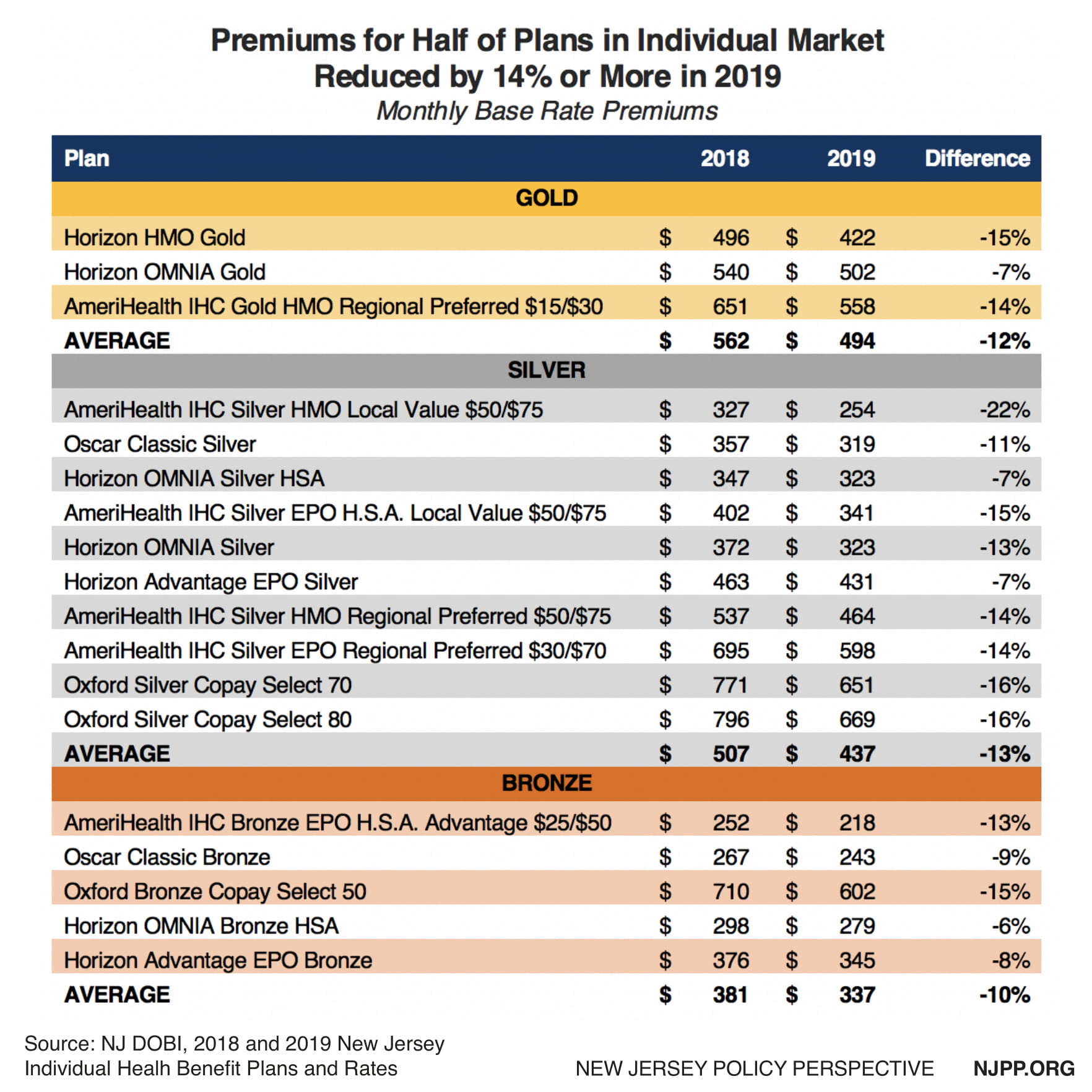

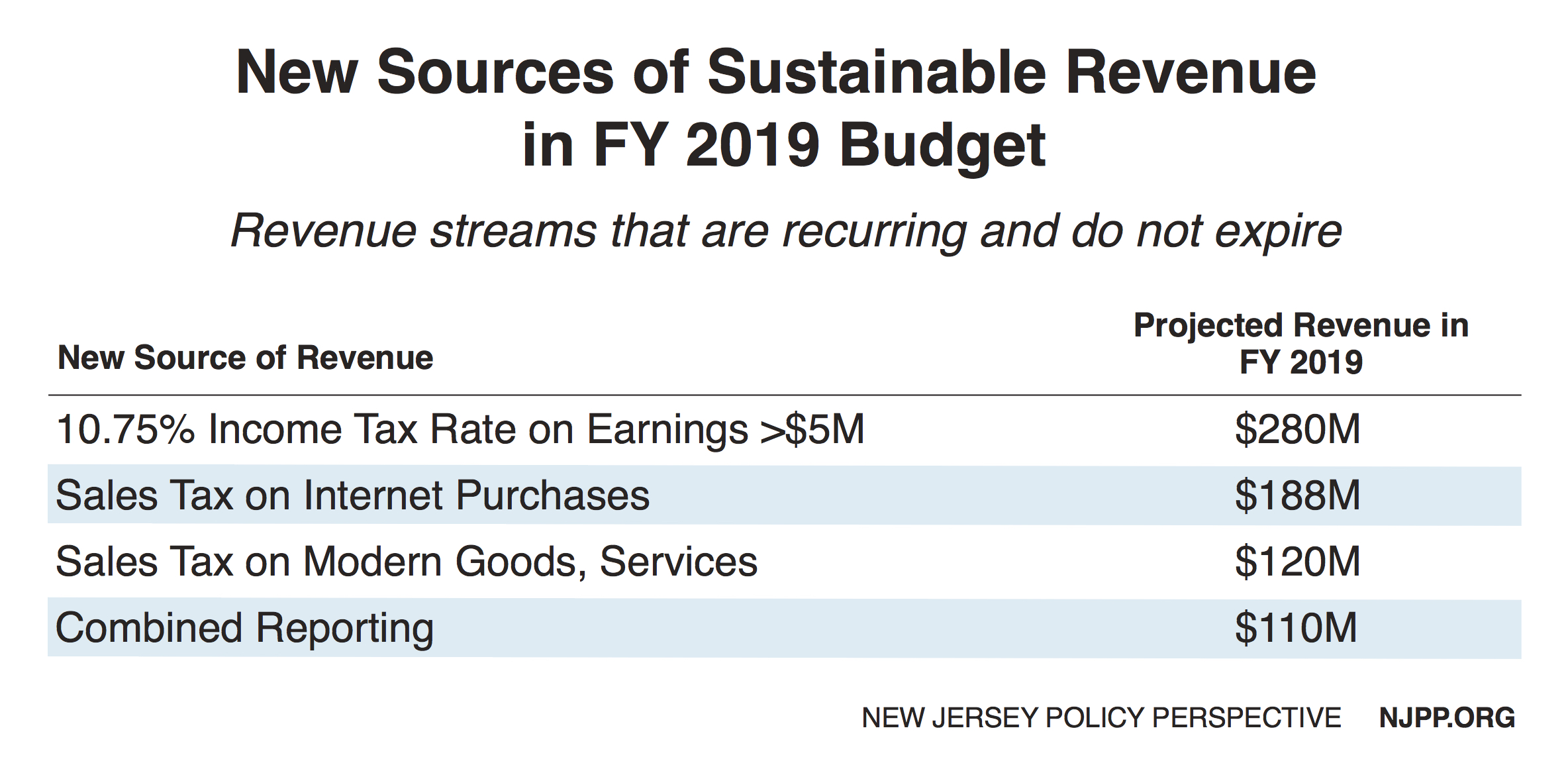

With a new governor in office, New Jersey has taken steps to correct course. Through advocacy efforts led by Planned Parenthood Action Fund of New Jersey, that funding has finally been restored. In addition, more people now have access to reproductive health services through the state’s Medicaid program which covers comprehensive contraceptives, abortion care, and prenatal care. More recently a pilot home visitation program providing parenting support to at-risk families has been established and $4.3 million in grants has been committed to address New Jersey’s dismal black infant mortality and maternal health rates.[4][5]

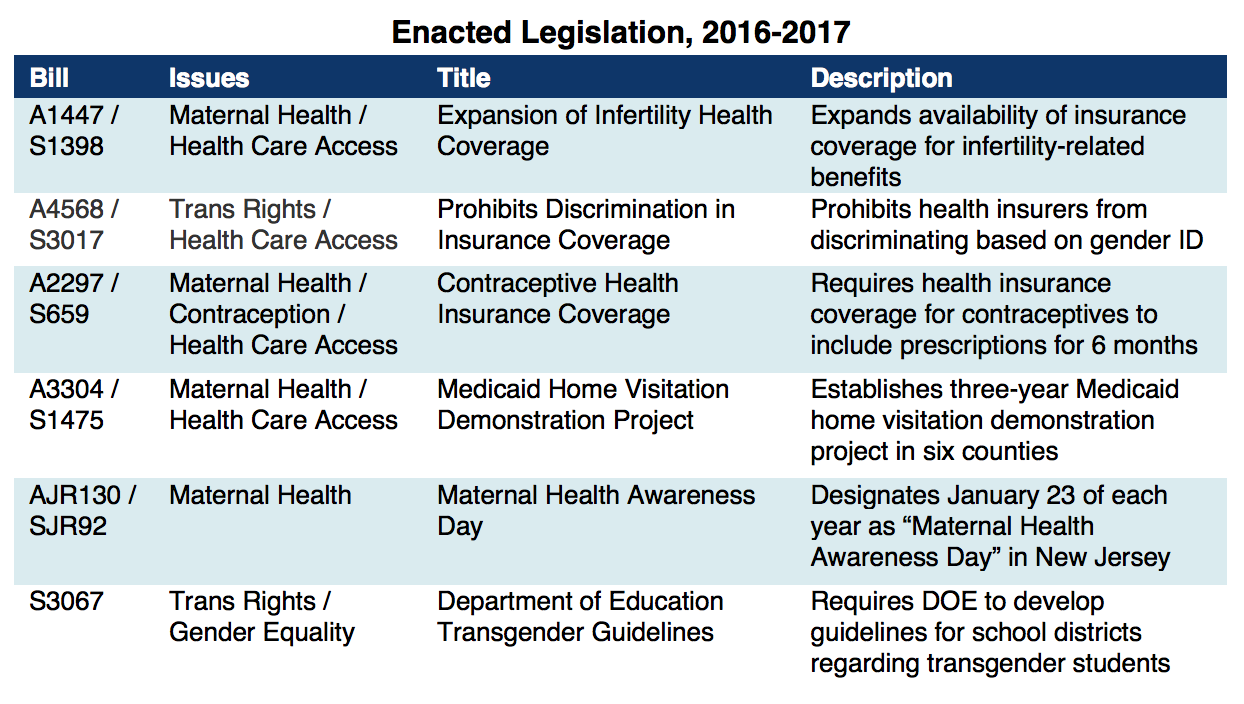

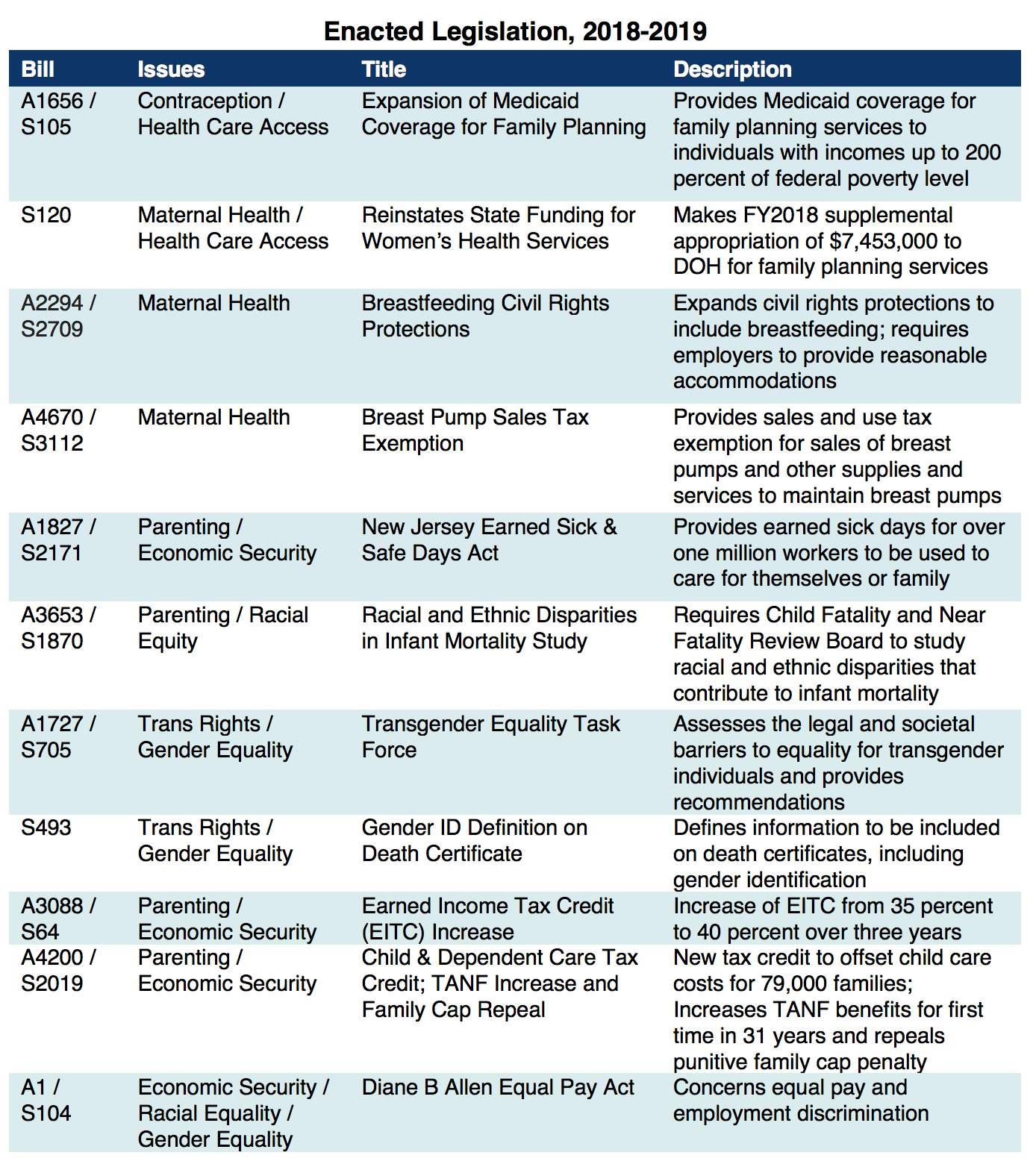

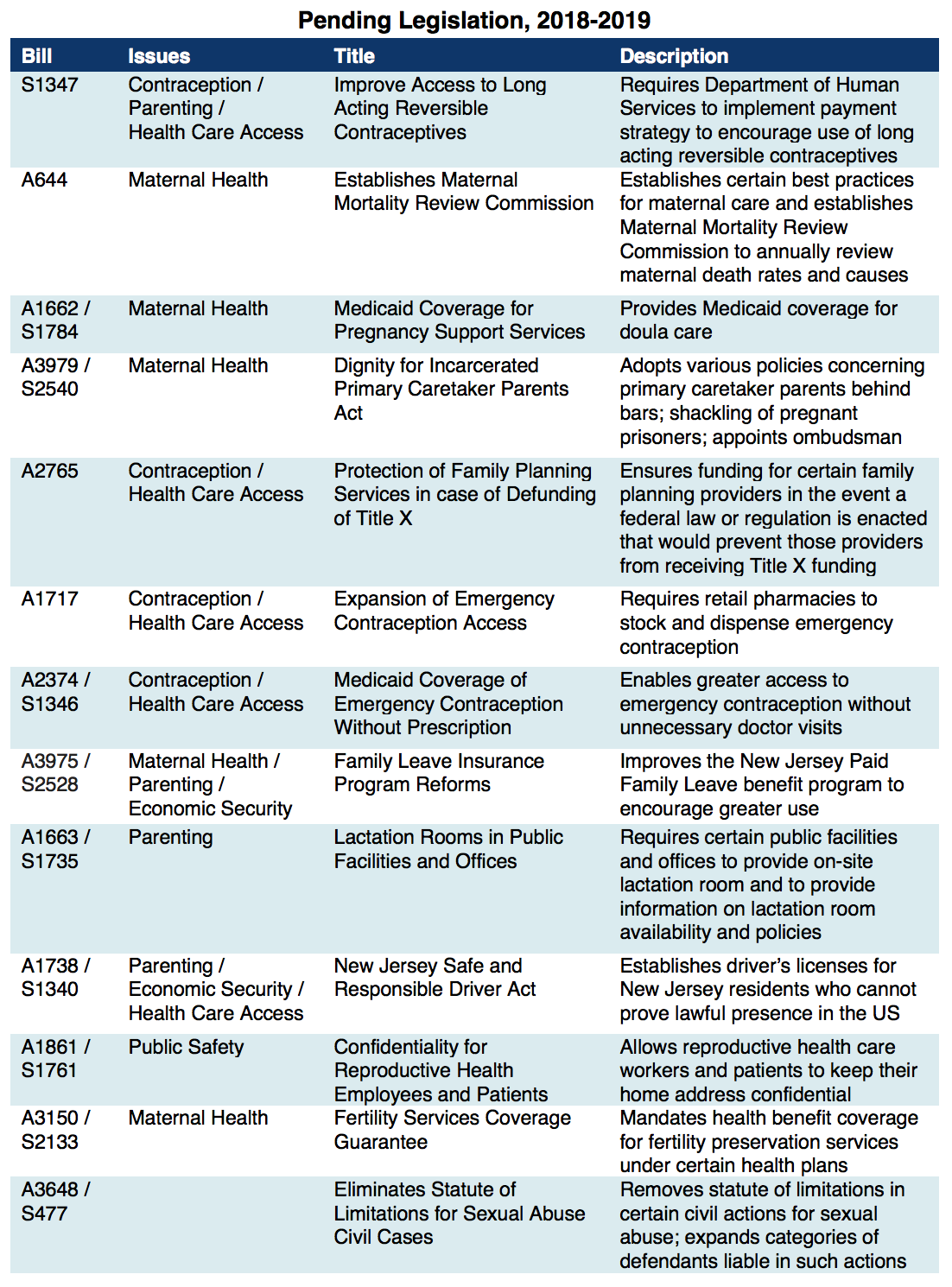

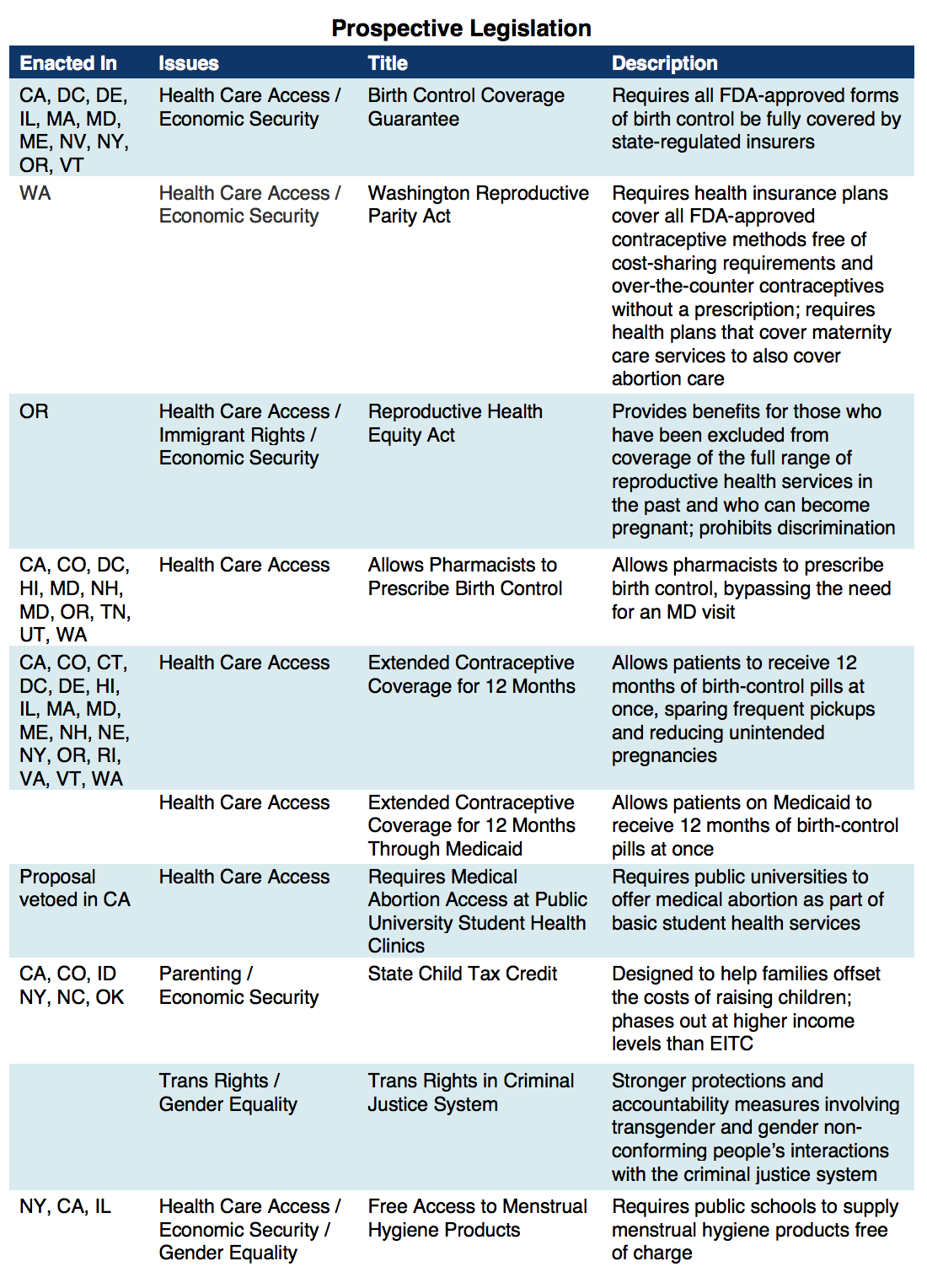

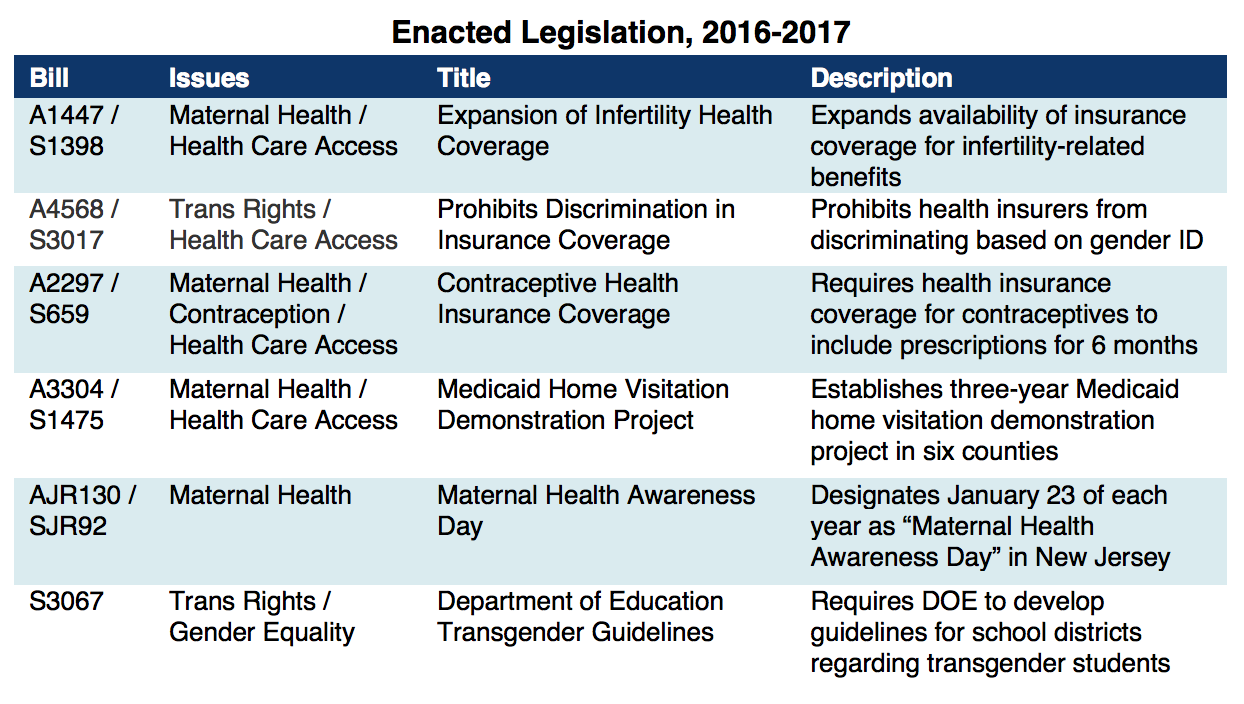

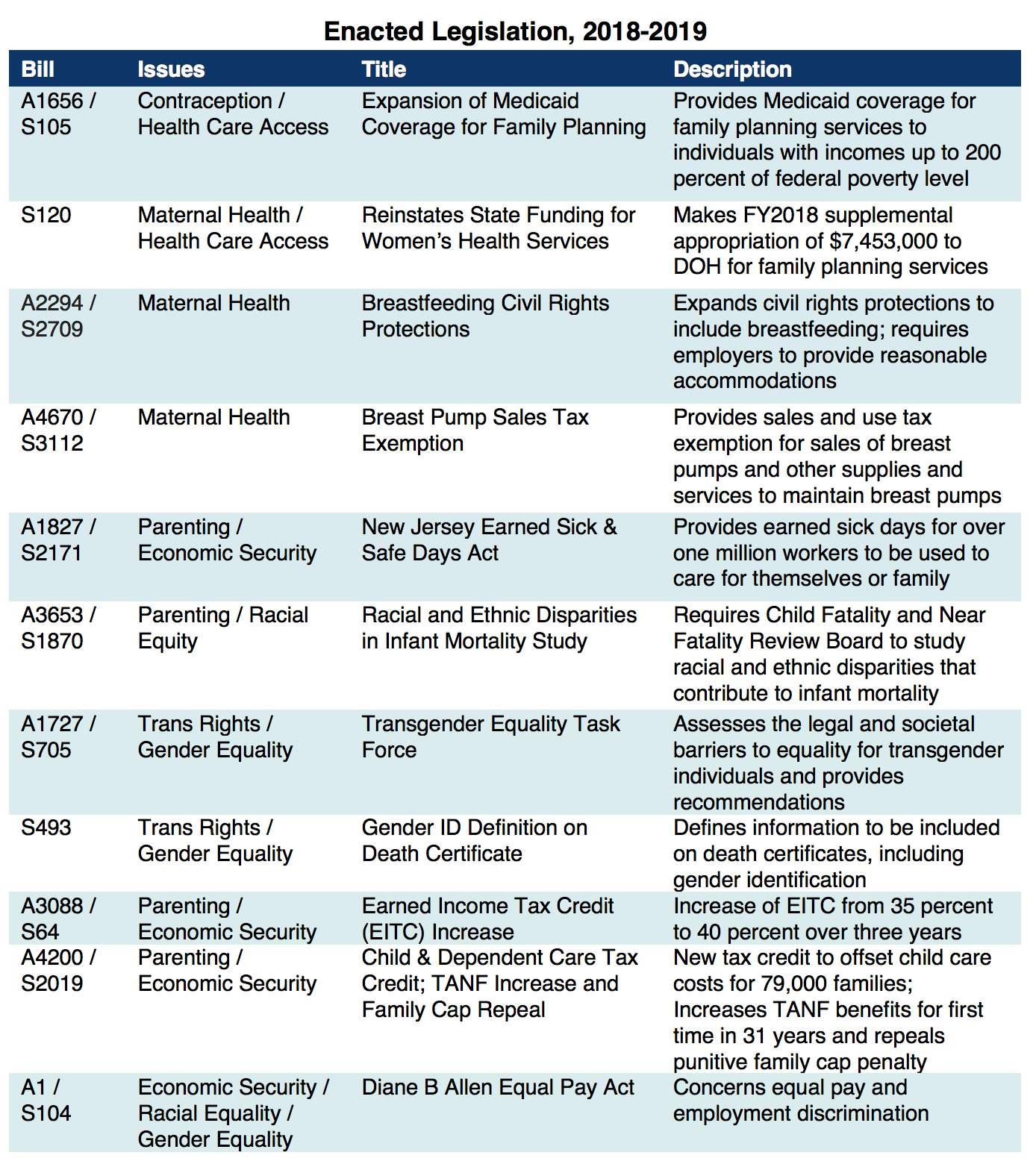

Still, there are many outstanding issues that demand policymakers’ attention. These issues persist because the advancement of reproductive health policy in the Garden State has failed to actively dismantle the ongoing, systemic oppression of women of color and other historically marginalized groups. When marginalized communities are absent at the forefront of a movement, chronic health care gaps and disparities can persist and worsen, harming the very communities most vulnerable to institutional injustice. Though presumably unintentional, the effect is ubiquitous. To improve reproductive health care access for everyone in New Jersey, policymakers must work to eliminate unnecessary barriers and focus resources on communities that historically have been the most disadvantaged. See Appendix II for examples of recent and pending legislation that represent the kind of forward-thinking policy agenda being advocated for in this report.

Improving Access to Contraception and Abortion

The scope of reproductive health care is not limited to contraception and abortion care, but these specific services have long been targeted for political reasons. Given the intensified political climate on the national level around reproductive health care access, it is vital that New Jersey defend these services from ideological attacks by expanding access through multiple avenues. In the following discussion of contraception and abortion, when we refer to people who can become pregnant, we emphasize the inclusion of women, transgender men, and gender non-conforming people.

Contraception

A person’s ability to plan, prevent, and space pregnancy is directly linked to their ability to access contraception. New Jersey has a responsibility to ensure that all people who can become pregnant, regardless of their circumstance, have control over their reproductive health decisions—and by extension their economic status—by removing unnecessary or outdated barriers to contraceptive services. New Jersey could begin by removing payment and logistical barriers that most impact communities vulnerable to patterns of institutional bias and discrimination.[6] Improving the lives and well-being of all families through better access to family planning services helps New Jersey conserve health care resources by reducing the number of unintended pregnancies, which cost the state over $185 million in 2010 alone.[7]

One immediate opportunity to remove harmful barriers is to require health insurance companies to provide a 12-month supply of birth control instead of 6 months—a measure that has been shown to cut down on both costly doctors’ visits and unintended pregnancies. According to a University of California, San Francisco study, dispensing a one-year supply of birth control at a time is associated with a 30 percent reduction in the likelihood of unplanned pregnancy.[8] Twelve states have mandated that health insurers cover an “extended supply” of birth control; several other states have pending legislation.[9]

Should federal efforts to defund Title X be successful, New Jersey must step in and ensure that low-income communities continue to receive family planning care in a seamless manner. The state Medicaid program should also address several lingering logistical barriers. For example, offering long-acting reversible contraceptives, like IUDs, to patients immediately after giving birth, would dramatically expand contraceptive options for low-income parents. But billing logistics have stymied widespread implementation. Just before the release of this report, a first step toward improving this important access gap has been addressed. Another technical fix to make the process seamless for both the health care provider and the patient is under review.[10] New Jersey should also allow Medicaid recipients access to emergency contraception (EC) without the unnecessary extra step of having to obtain a prescription first—a logistical barrier left over from the George W. Bush era.[11] Requiring all retail pharmacies in the state to stock and dispense EC would greatly improve people’s ability to obtain this time-sensitive medication as well as improve another avenue toward reducing the rate of unintended pregnancy.

Abortion Care

New Jersey has upheld the right to abortion care since the procedure was legalized under Roe v. Wade. Just as importantly, the state has largely remained outside the national trend of state-level abortion restrictions like waiting periods and gestational limits. Across the country, over 1,000 anti-abortion laws have been enacted with a notable increase in the last several years.[12] In fact, the state Constitution has been interpreted to provide more expansive protections for the right to privacy and the right to end a pregnancy than the federal Constitution does, even with the protections of Roe v. Wade.[13] Yet, barriers to abortion care remain in the Garden State, primarily due to inadequate insurance coverage and efforts by anti-abortion organizations to diminish access through harassment, intimidation, and deception. For uninsured or under-insured individuals who wish to end a pregnancy, the cost of care can be out of reach. According to a 2014 Guttmacher Institute national survey, 75 percent of abortion patients are low income and a majority paid for their abortion care out of pocket, even though most had health insurance coverage. Due to the large number of patients paying out of pocket for services, abortion providers have strived to maintain affordable cash fees. Still, the financial expense of accessing abortion care extends beyond the medical cost with a substantial number of patients reporting additional expenses such as transportation, childcare, and lost wages.[14] When faced with these unexpected expenses, some patients may be forced to delay paying bills, borrow money, or seek assistance from a privately-run abortion fund like the New Jersey Abortion Access Fund—options that can create unnecessary delays.

Before Roe v. Wadelegalized abortion nationwide, the class divide in access to the procedure was clear cut. Those in need of abortion care but without financial resources had no access to safe medical services. Those with means travelled to states like New York where the procedure was legalized in 1970. In the first two years, 60 percent of abortion patients were from outside the state.[15] AfterRoe, the Hyde Amendment was swiftly enacted, blocking all federal funds from paying for abortion information, referrals, or care. Recognizing this clear violation of state control over reproduction and decision-making, New Jersey opted in to use state funds to support Medicaid access to abortion services thereby mitigating the impact of the Hyde Amendment. New Jersey remains one of only twelve states to do so.

Despite this decades-long commitment, many abortion providers in New Jersey struggle to cover costs due to low reimbursement rates from both Medicaid and the private insurance sector. Even when private insurers have appropriately negotiated reimbursement rates, many people are still unable to utilize their policies to access abortion care. For example, some private policies do not cover abortion services for policy holders or dependents, or policies may have increasingly high deductibles, which forces many patients to pay for services out-of-pocket.[16] The overall effect of underfunding leaves health centers trying to provide high-quality care to everyone regardless of ability to pay while keeping the doors open in a safe environment for patients and staff. Independent abortion providers, committed to maintaining meaningful access to abortion care throughout pregnancy while enduring the bulk of harassment by anti-abortion extremists, feel this financial strain most acutely. As reproductive rights continue to erode across the county, now is the time for New Jersey to invest in expanding and preserving abortion access.

Increasing Medicaid Reimbursement Rates for Abortion Providers: A Case Study

Cherry Hill Women’s Center (CHWC), a premier independent abortion provider in Camden County, New Jersey, is a prime example of this struggle. CHWC specializes in providing first and second trimester abortion care and other reproductive health services, inspired by their belief in the autonomy of the individual and their commitment to strengthening communities. Yet, because abortion care is a highly politicized and stigmatized health service, it carries its own set of unique challenges and obstacles that increase operating costs.

For decades, abortion providers have faced the risk of violence at the hands of anti-choice extremists, creating unusual security needs that other health care facilities do not have. This includes security guards, secure entry, 24-hour closed-circuit video cameras, bullet-proof glass, high-level security trainings, and coordination of clinic volunteers to escort patients through protestors. Screening of patients, staff, and vendors is needed to eliminate the opportunity for anti-abortion extremists to breach security, violate privacy, and/or commit violence. All these safety measures require resources that may need to be diverted from health care services and clinic sustainability. Given the alarming increase of anti-abortion rhetoric at the federal level, there has been a notable increase in violence meant to disrupt care and intimidate patients and staff members.[17]

The threat of violence also has a ripple effect on other aspects of operating an independent abortion clinic like CHWC. It makes it more difficult to contract necessary services, such as facility maintenance, medical waste disposal, and the purchasing of medical supplies. Targeting by anti-abortion extremists also makes it difficult to recruit and retain medical professionals to perform abortion procedures due to their own safety and privacy concerns. Abortion providers are already hard to recruit due to limited access to training, low-reimbursements, and increasingly high insurance costs.

Medicaid reimbursement rates fail to consider not only the true cost of health care, but the unique costs associated with providing abortion care in a safe and secure setting. Simply put, Medicaid reimbursement rates for abortion care have not kept pace with medical care costs and certainly do not account for the complex challenges faced by abortion providers.[18]

Taken as a whole, abortion providers remain at an economic disadvantage due to the burden of these unavoidable extra costs. As it stands, the United States has a limited number of facilities qualified to provide abortion throughout all stages of pregnancy, particularly the third trimester. Policymakers looking to improve and expand abortion access in New Jersey can start by increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates for a medical service that has been politicized and stigmatized for far too long.

Fake Women’s Health Centers

Everyone deserves unbiased, evidence-based health information, regardless of their zip code or financial situation. In New Jersey, this value is exemplified by mandated comprehensive sex education curriculum. Thorough and accurate sexual health education provides young people with the tools they need to make decisions about their health and well-being. Unfortunately, there are organizations operating in New Jersey with the sole intention of derailing access to legitimate reproductive health care services.

Fake women’s health centers, or crisis pregnancy centers, have become a well-established tactic used by anti-abortion extremist organizations with the intention of misleading women seeking pregnancy options, counseling, or abortion care.[19] They use false and deceptive advertising to lure unsuspecting pregnant women to a facility staged to look like a legitimate health care clinic, where staff attempt to coerce them to continue their pregnancies using false medical information, shame, and religious rhetoric.[20] Some of these unlicensed, unregulated “clinics” even provide cursory health services like ultrasound imaging to manipulate women.[21]

Fake women’s health centers have also infiltrated the public school system, offering supplemental abstinence-only sex education based in misinformation and stigma.[22] This puts students at a dangerous disadvantage, making them vulnerable to deception when accessing reproductive health care in the future. This kind of lapse speaks to the need for a comprehensive inventory of New Jersey’s existing sex education curriculum and funding sources, which includes federal “abstinence-only” dollars.[23] Fortunately, a review of New Jersey’s existing sex education curriculum for grades one through 12 is scheduled for 2019. Plans to re-evaluate federal contracts, update the standards, develop sample lesson plans, provide more sex education training for teachers, and incorporate an evaluation tool to ensure accountability are important steps toward getting New Jersey back on track as a strong supporter for comprehensive sex education.

But more commonly, fake women’s health centers target vulnerable women by burgeoning in underserved communities and offering their services free of charge, potentially increasing systemic inequalities.[24][25] Similar to the sex education example above, the proliferation of these health centers in New Jersey is an indicator of ongoing gaps in health care access. Most New Jersey counties have only one family planning clinic, and nearly one in four women live in a county with no abortion provider at all.[26] These gaps put those with limited finances and access to transportation at risk of being duped by fake women’s health centers. Addressing these gaps by increasing the availability and access to qualified health care providers, as well as clearly indicating where people can access these services, will have the biggest impact on the lives of New Jersey women seeking legitimate reproductive health care.

Addressing Maternal and Infant Mortality Disparities

When maternal health care needs go unmet—whether incidentally or systematically—the health and well-being of parents and children are put at serious risk. For decades, New Jersey’s Black families have been at a greater risk than anyone else.

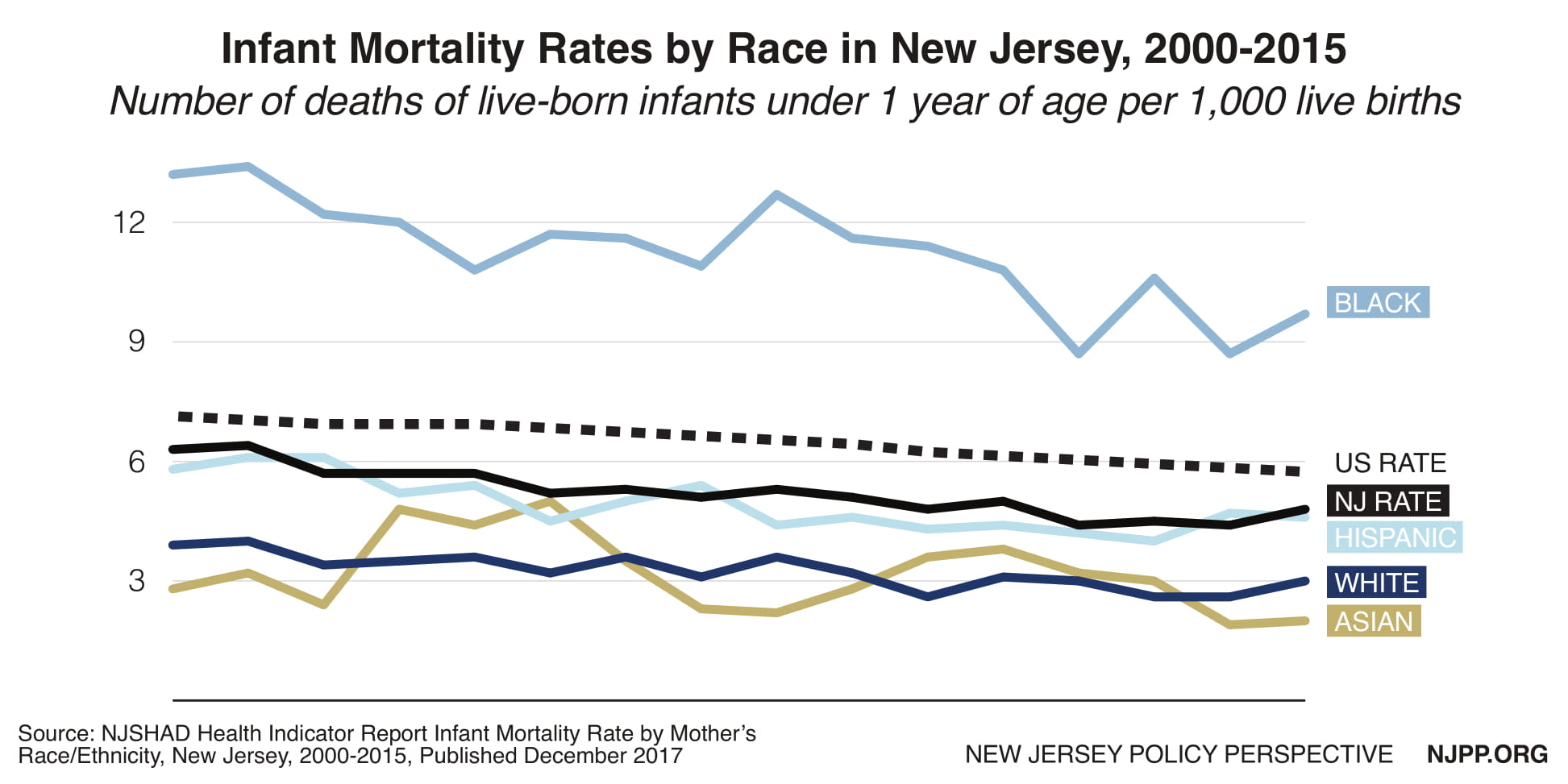

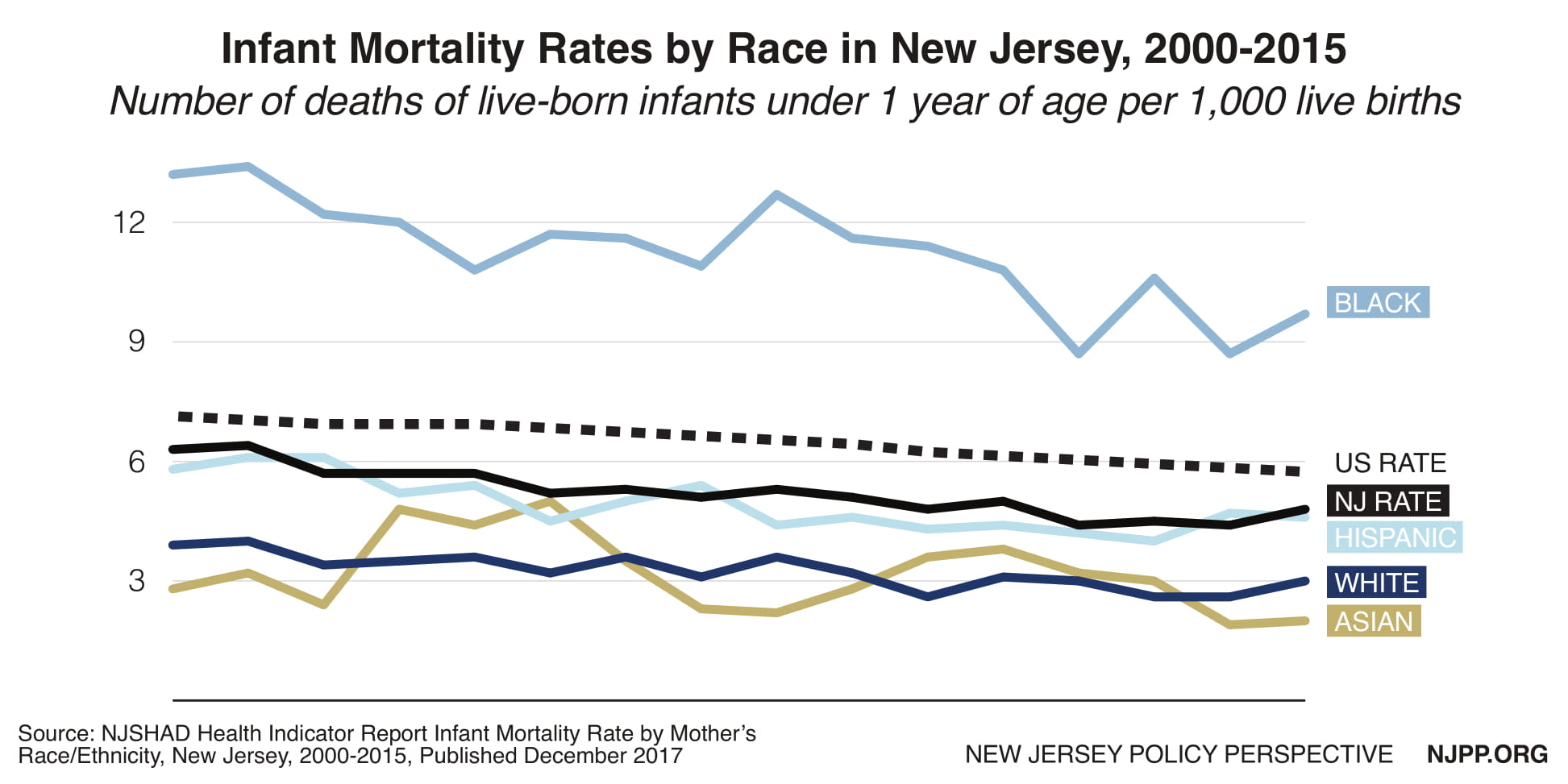

While the overall maternal death rate in New Jersey has improved over time and is below the national rate, enormous racial disparities have persisted. Black women in New Jersey are more than four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications as white women.[27] Similarly, the likelihood of a New Jersey infant dying before their first birthday has recently dropped and is slightly lower than the national rate. Yet, the disparity between white and Black infant mortality in New Jersey is the worst in the country. A Black infant born in the Garden State is three times more likely to die than a white infant, regardless of their mothers’ income level or educational attainment.[28]

Research suggests that Black women are susceptible to dangerous pregnancies and birth outcomes due to “weathering,” the cumulative effects of racism on one’s health and well-being.[29] The chronic stress of discrimination in all aspects of society—from housing to employment to picking up groceries—may negatively affect the body causing it to age prematurely. These effects may “weather” African American women more acutely than other women resulting in high-risk reproductive health issues.[30]

New Jersey’s dismal Black maternal mortality rate is not breaking news to the state’s Health Department. Since 1931, it has reviewed maternal health outcomes with detailed research about the root causes of its high maternal mortality rate and possible causes of the stark racial and ethnic disparities. But, like other states, New Jersey has failed to find long-lasting solutions to close the racial gap in maternal health. With a new governor in office, interest in the issue has been renewed. Another maternal mortality review commission has been established, a proposed infant mortality review board is moving through the legislature and grants have been awarded to community-based organizations in high-risk areas to help coordinate maternal care including doula pilot programs in Newark and Trenton.

These targeted efforts are based on similar work taking place North Carolina, one of the few states that have successfully closed the racial gap in maternal health.[31] Doctors there are incentivized through Medicaid reimbursements to screen pregnant women for issues that may trigger a high-risk pregnancy. Patients that have either physical or psychological risks are connected to a “pregnancy care manager” who helps expectant mothers follow their care plan by addressing a wide range of barriers. The North Carolina Pregnancy Medical Home program provides support for everything from access to insulin to housing issues to helping offset both the physical stress of pregnancy and the physical stress in one’s life that has real consequences on one’s health.

In addition to the state-supported medical home model, over 60 North Carolina birthing hospitals have conducted several statewide quality improvement efforts including cutting down on inducing birth before a baby’s due date and improving rapid response treatment of mothers with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia—two of the most severe and dangerous health issues among African American mothers.

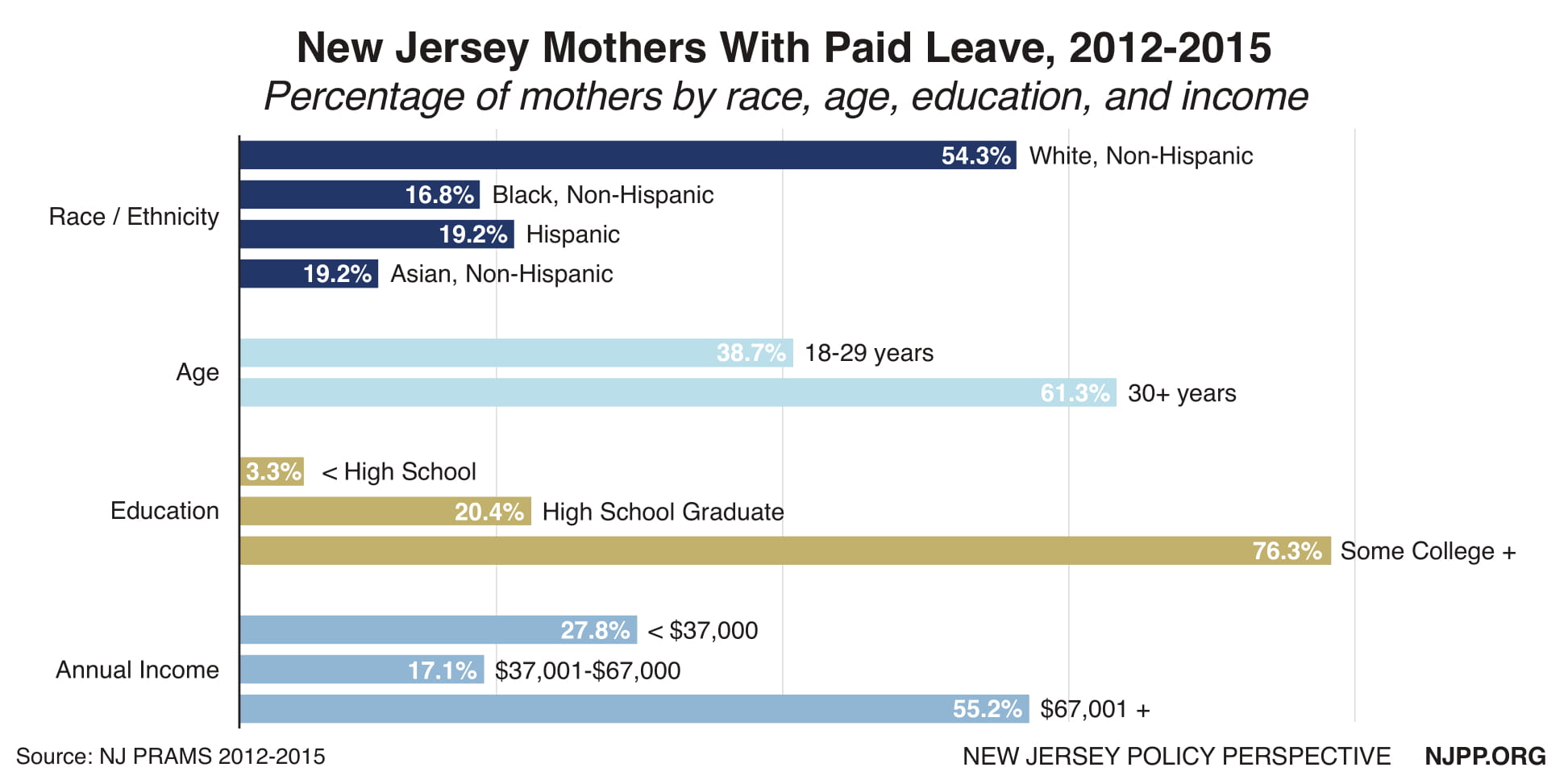

Studies also show that in countries with a generous parental leave policy there are tremendous effects on morbidity and mortality rates of infants and young children.[32] New Jersey is one of only four states that have implemented a paid leave policy providing workers and their families the opportunity to take time off work to bond with a new baby or adopted child or care for an elderly or very sick family member. However, very few New Jersey workers utilize the program because they are either not aware of it, or they fear negative repercussions at work, including job loss. In addition, workers struggling to balance work and family caregiving simply can’t afford the low wage replacement rate that is offered by the program.

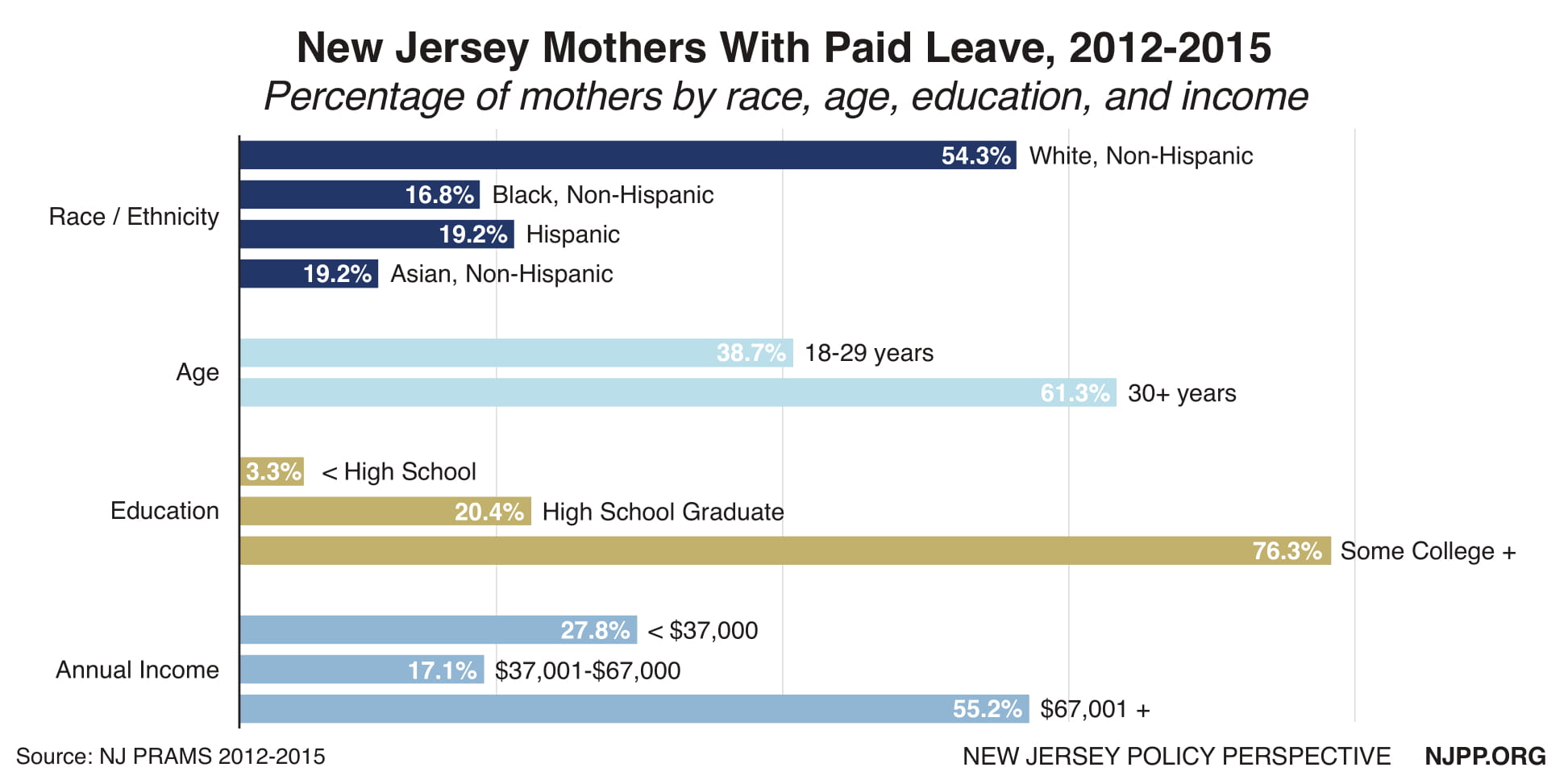

Meanwhile, there are stark disparities among New Jersey mothers who take paid leave. Between 2012 and 2015, white women in New Jersey were 3 times more likely to take leave than Black women.[33] National research has shown that workers of color are more likely to work for firms that don’t offer family leave insurance.[34] New Jersey is poised to make major improvements to its existing Family Leave Insurance program including promotional efforts so that more workers take advantage of the program. However, the current bill may leave 750,000 workers without job protection putting their household economic security at risk.

The next step for New Jersey is to strengthen its Family Leave law and move beyond demonstration projects and pilot programs. One key component to addressing racial disparities in maternal health care is found in making the leap toward sustainable funding for medical home models in at-risk communities, higher Medicaid reimbursement rates for obstetric services in the hospital setting, and Medicaid coverage for related services including doula care and home visitation.

In fact, state legislators have recently introduced a bill to provide state Medicaid coverage for doula services. Doula care, non-clinical emotional, physical, and informational support before, during and after birth, is associated with lower caesarian section rates, fewer obstetric interventions, fewer complications, shorter labor hours, and healthier newborns. These improvements are critical for Black mothers who are disproportionately at risk for pregnancy-related complications and are routinely subjected to the inherent biases of medical staff that can have life or death consequences.[35] Doula care has been proven to reduce health disparities, improve health outcomes, and improve quality of care, especially in low-income communities.[36] Studies have shown potential cost savings, even if doula care services are partially covered.[37]

Dignity for Those Incarcerated

Regardless of circumstance, everyone deserves to be treated with dignity. In the prison setting that includes having the right to serve a sentence free of abuse, to access appropriate health care, and to maintain parenting obligations. Key criminal justice policy reform like the expansion of drug courts and the overhaul of the bail system has helped New Jersey reduce its prison population by almost a third (28 percent) since 2000.[38] That trend has fared better for New Jersey women as the men’s prison population has declined by a smaller proportion.

Still, stark disparities persist. According to a 2016 report, New Jersey has the nation’s highest rate of Black/white disparity with African Americans being incarcerated in state prisons 12 times the rate of imprisonment of whites.[39] As a comparison, the national disparity rate is five to one.

To the state’s credit, a newly mandated racial and ethnic impact statement provides an overdue opportunity for lawmakers to address this glaring disparity by reviewing a statistical analysis of the impact of proposed criminal justice policy changes. It is a vital first step toward making informed decisions about improving public safety without exasperating existing racial disparities. Now it is time for policymakers to do the same for gender disparities in the criminal justice system.

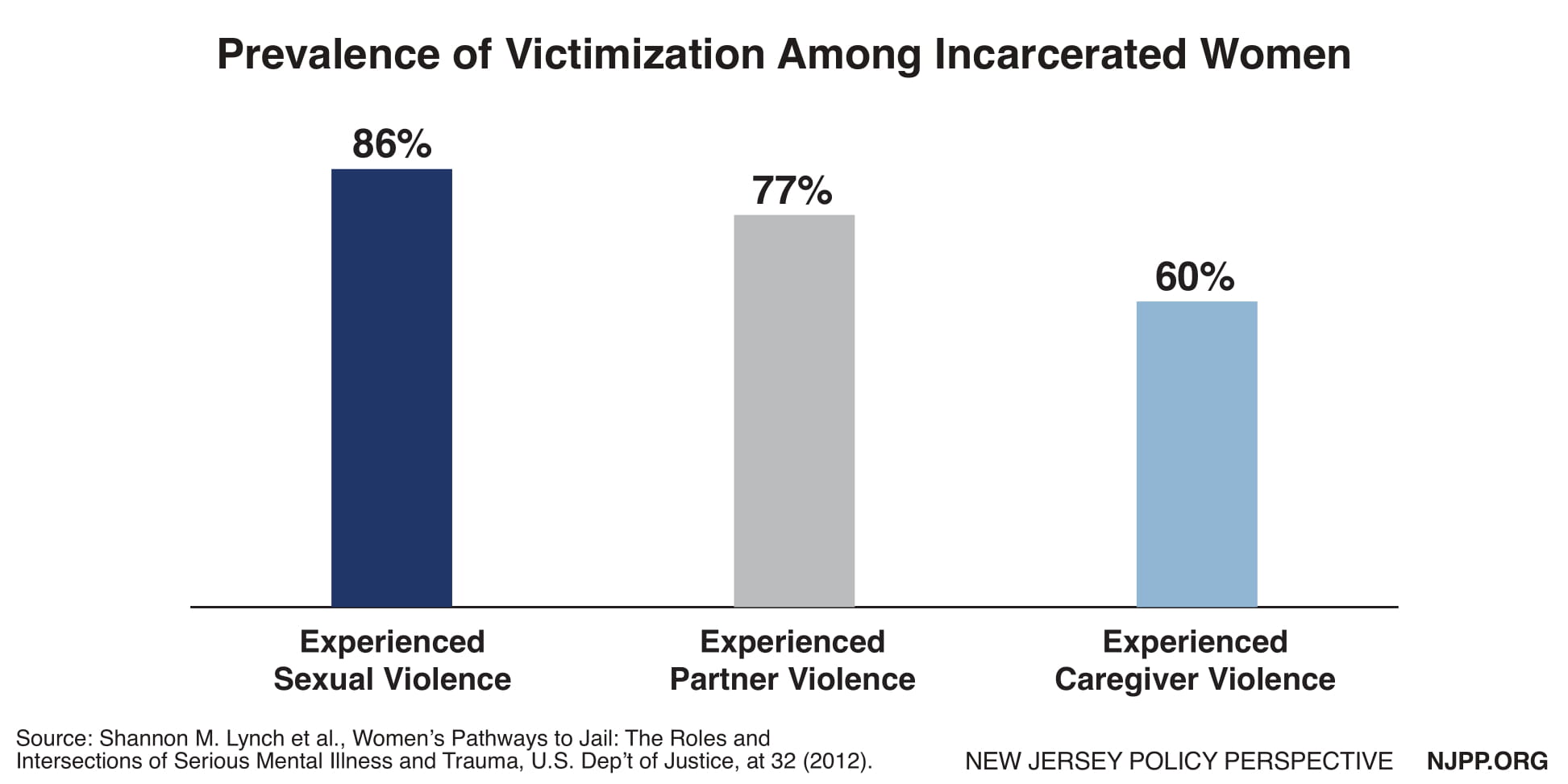

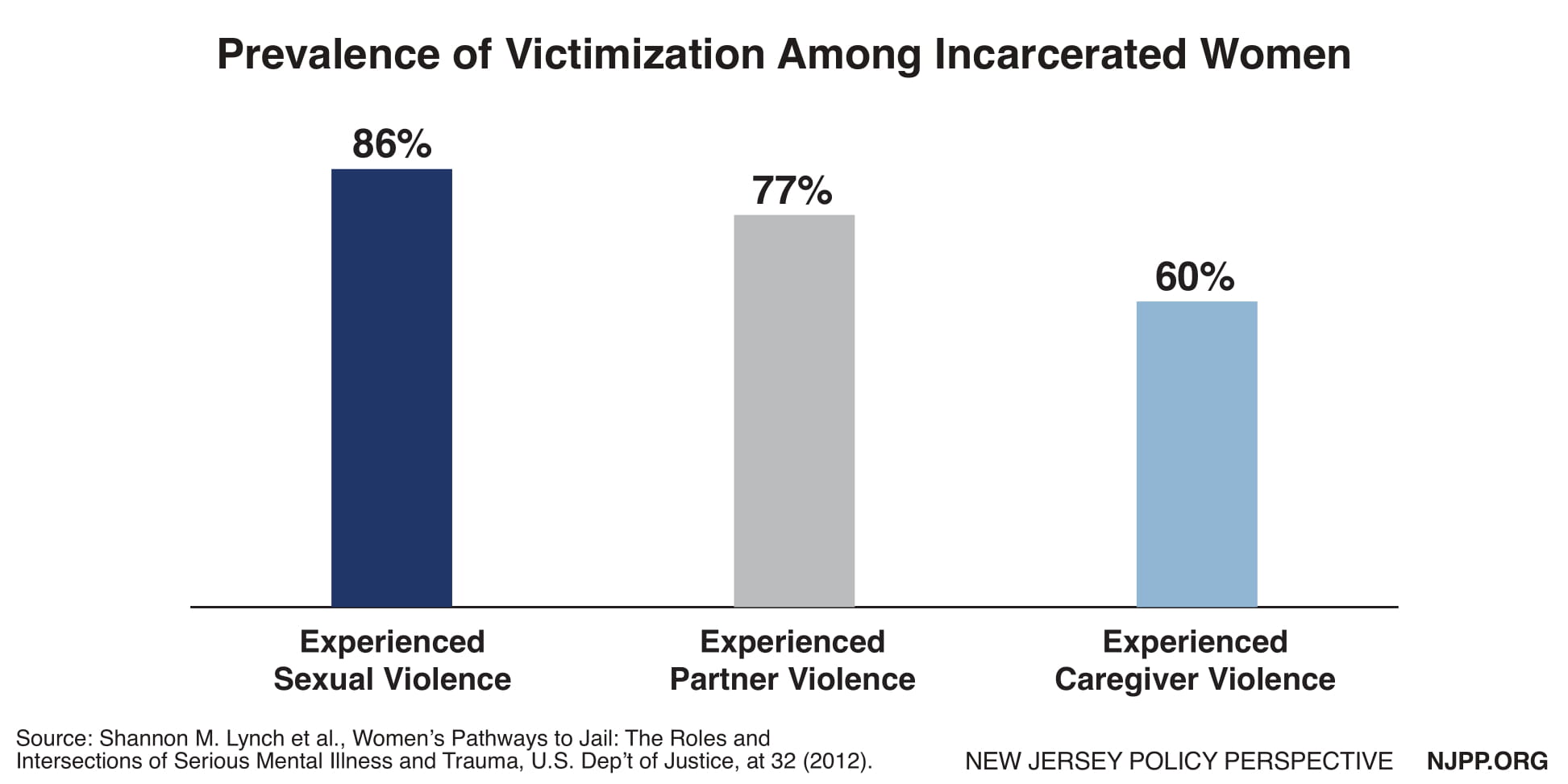

Multiple studies show that there is a direct link between women with a history of trauma, substance use disorders, poverty, and mental health problems and their eventual contact with the criminal justice system, where these problems are often exacerbated. New Jersey’s only women’s prison serves as a sobering example.

The Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women, which houses about 650 inmates, is currently the subject of at least 11 lawsuits related to sex abuse allegations including a class-action suit that details a history of abuse at the prison since the early 1990s.[40] An independent review has been commissioned by the State Attorney General’s Office and a federal civil rights investigation is underway. Four staff members have been convicted, and three other correctional officers face trial.

Despite laws and procedures in place to ensure the safety of inmates, the Department of Corrections has systematically failed to protect these women. Policymakers’ response to this horrific pattern of abuse and inaction has been to propose ways of improving existing procedures. This is a missed opportunity to look beyond the deficiencies of the correctional system and instead shine a spotlight on the unmet needs of Edna Mahan’s prison population.

According to the Vera Institute for Justice, many jailed women experience mental illness and extremely high rates of victimization—including childhood sexual abuse, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence.[41] New Jersey’s correctional system has not only failed to properly treat women inmates, it has re-traumatized women through unchecked abuse of power. Even standard practices such as strip searches have the potential to retraumatize victims of sexual assault. A former inmate involved with the class action lawsuit said she came forward to help women like herself who “had to live with monsters just to come to a different place and have to live with a new set of monsters.”[42]

To improve conditions at Edna Mahan, state legislators have introduced bills that are primarily focused on codifying existing policy, including the prohibition of shackling pregnant women, limitations on the use of strip searches, and the expansion of the correctional ombudsman’s role to include sexual assault.[43] While these responses are notable, more must be done.

New Jersey’s criminal justice system is one that is primarily designed for the incarceration of men. To improve conditions in a meaningful way, reform must begin with identifying the unique needs of a prison population comprised entirely of women. An inclusive overview of Edna Mahan’s population would provide an opportunity to improve and expand access to health care that meets the needs of its inmates, including reproductive health care for individuals across the gender spectrum. This path toward meaningful reform should begin with policymakers sitting down with formerly incarcerated women and advocates who represent the interests of incarcerated women.

Expanding Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants

Health care access is a fundamental right for everyone regardless of where they come from or how they arrived in the country. Yet, this right is routinely denied to undocumented families living in New Jersey due to financial and travel barriers to health care services.

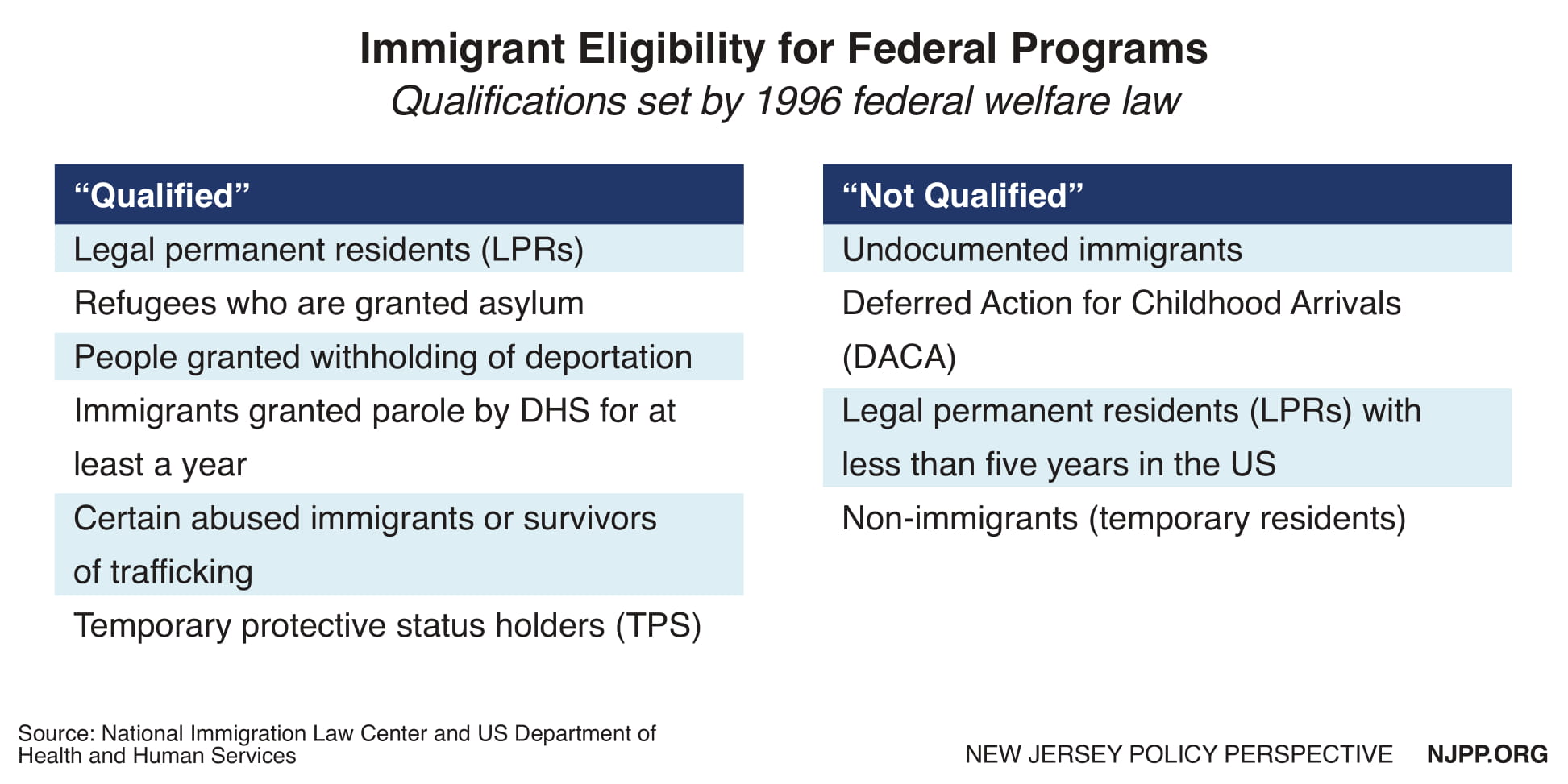

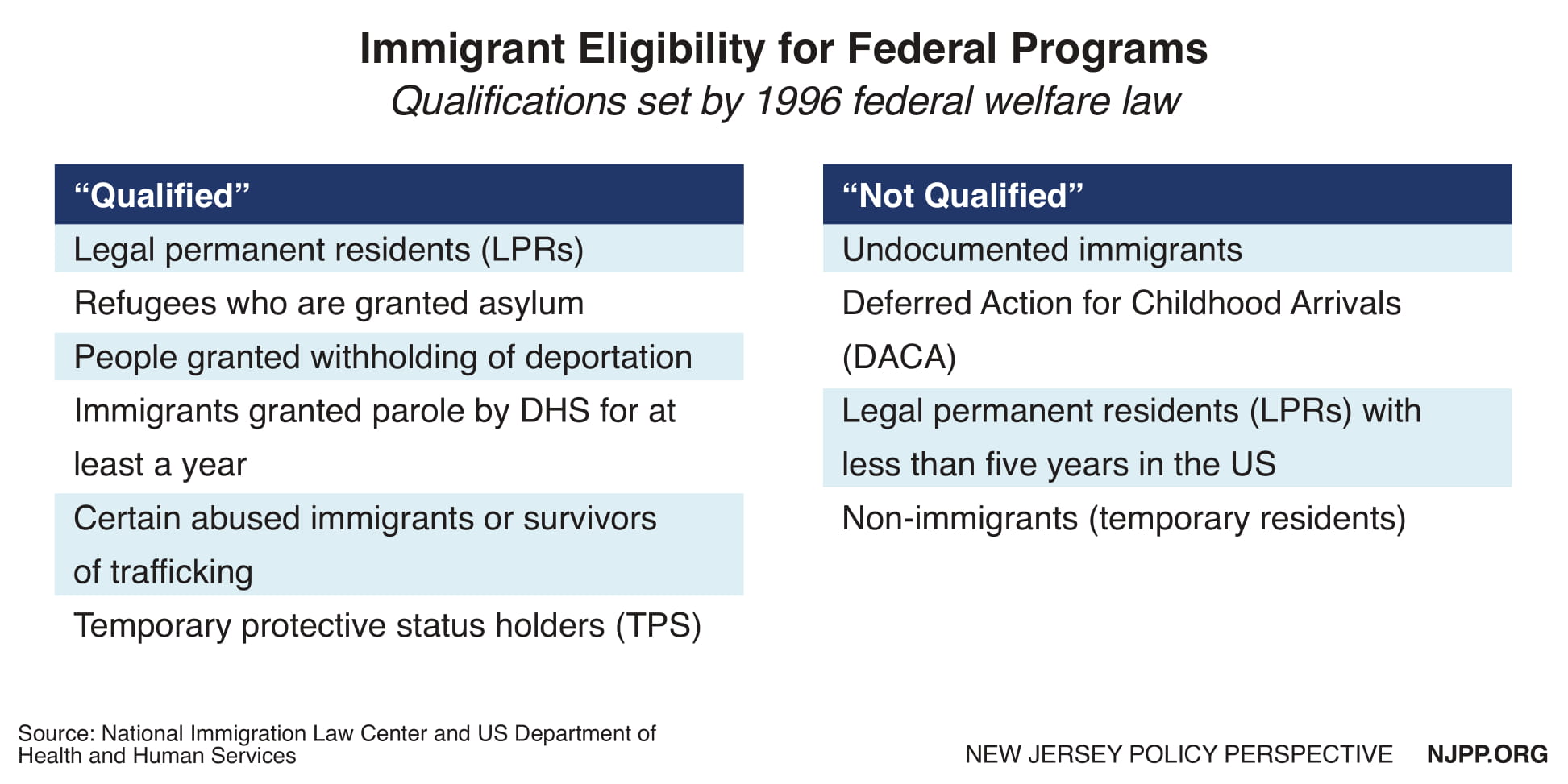

Federal restrictions to programs that provide health care coverage, job-training, nutrition, and cash assistance vary depending on the immigration status of noncitizens. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act/Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 created two categories of immigrant community members: “qualified” or “not qualified.”[44] In addition, the federal law banned legal immigrants who are permanent residents or green card holders from accessing a variety of welfare services or health care programs for a period of 5 years beginning on the date of entry into the United States.[45]

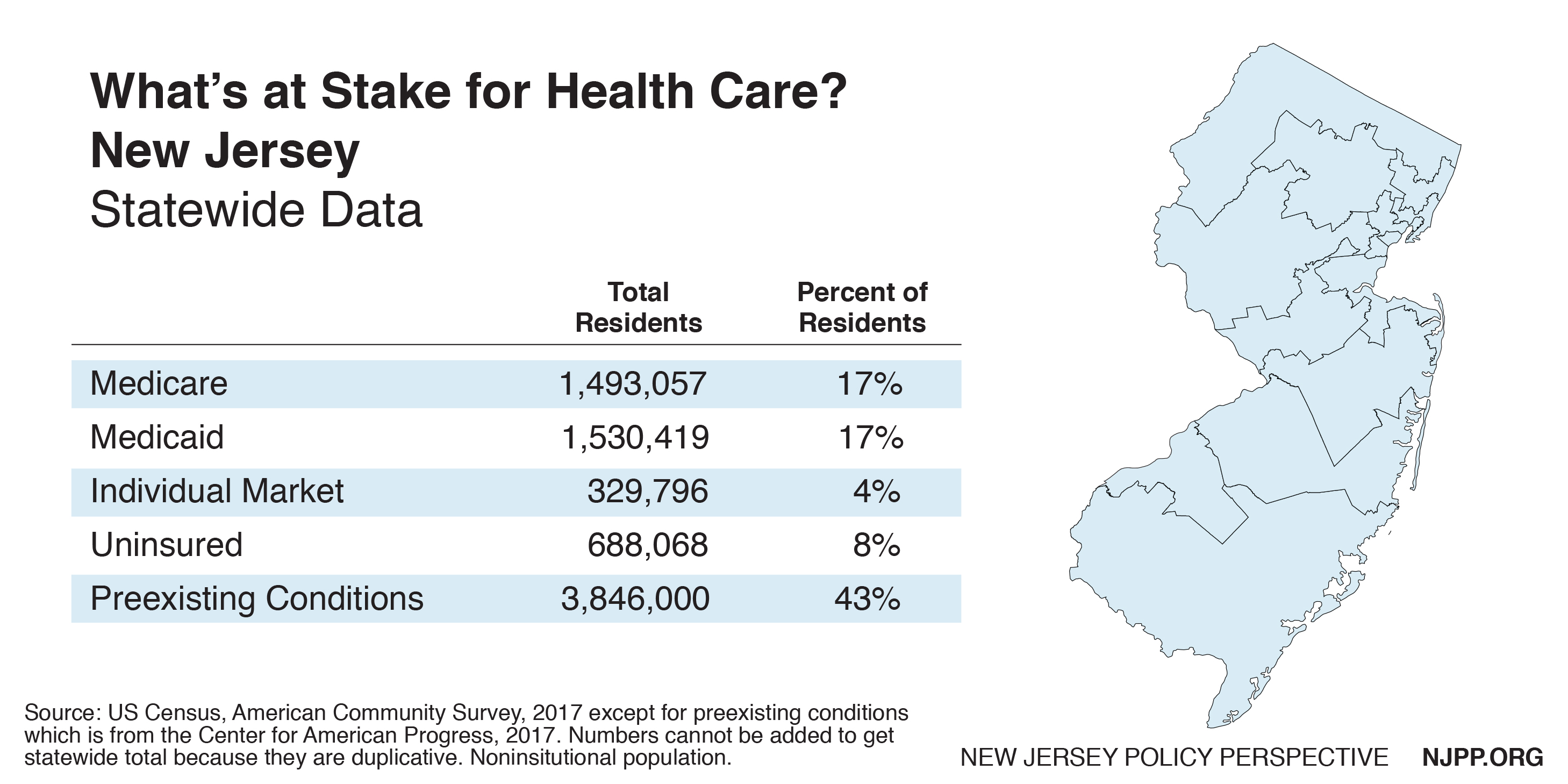

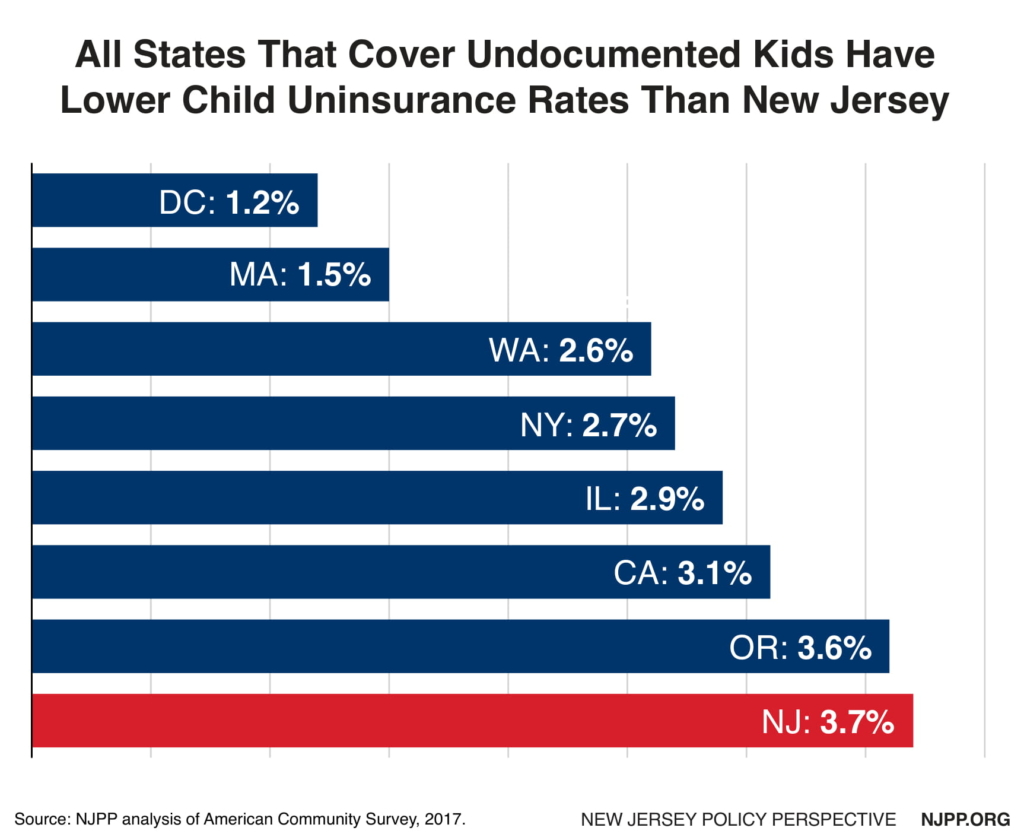

However, states do have the power to implement their own health care policies. For example, state health plans in six states and Washington D.C. cover all children, regardless of immigration status and health plans in 17 states cover all pregnant women, regardless of immigration status. New Jersey is not among these states, but there is movement to change that.[46][47]

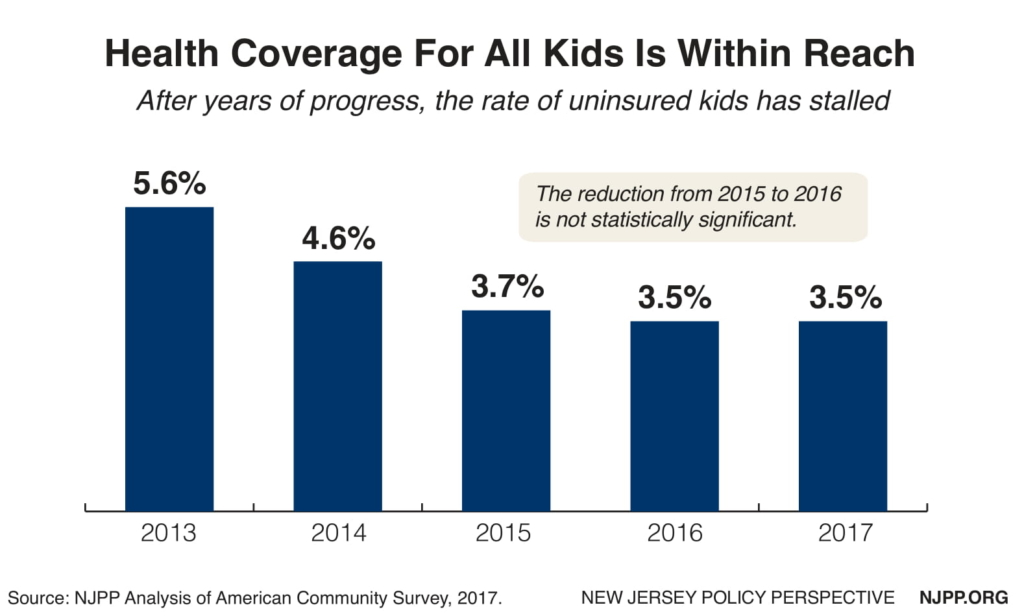

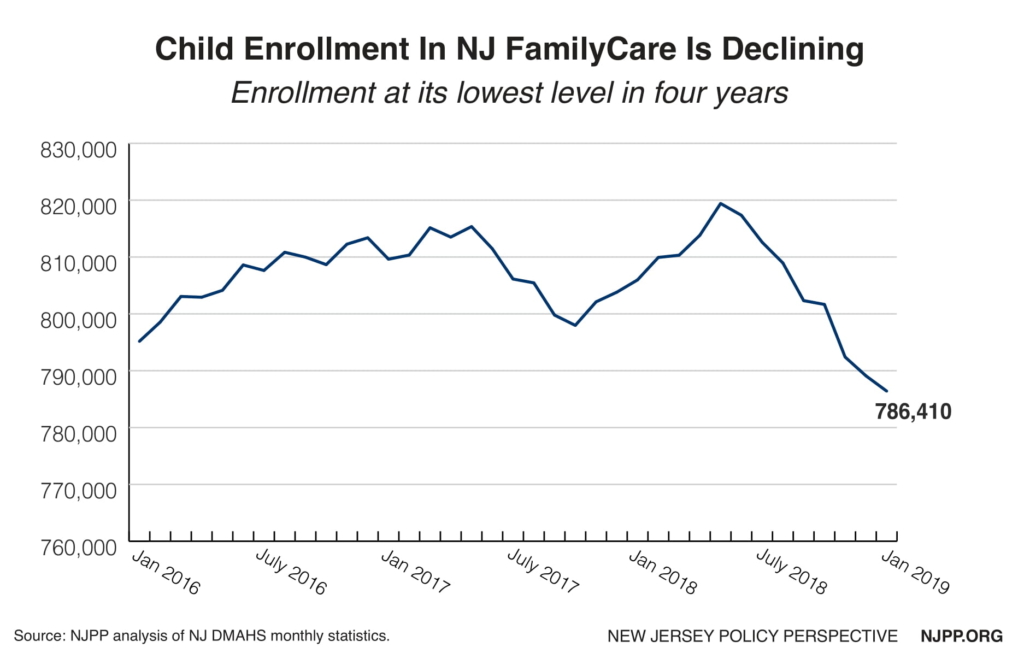

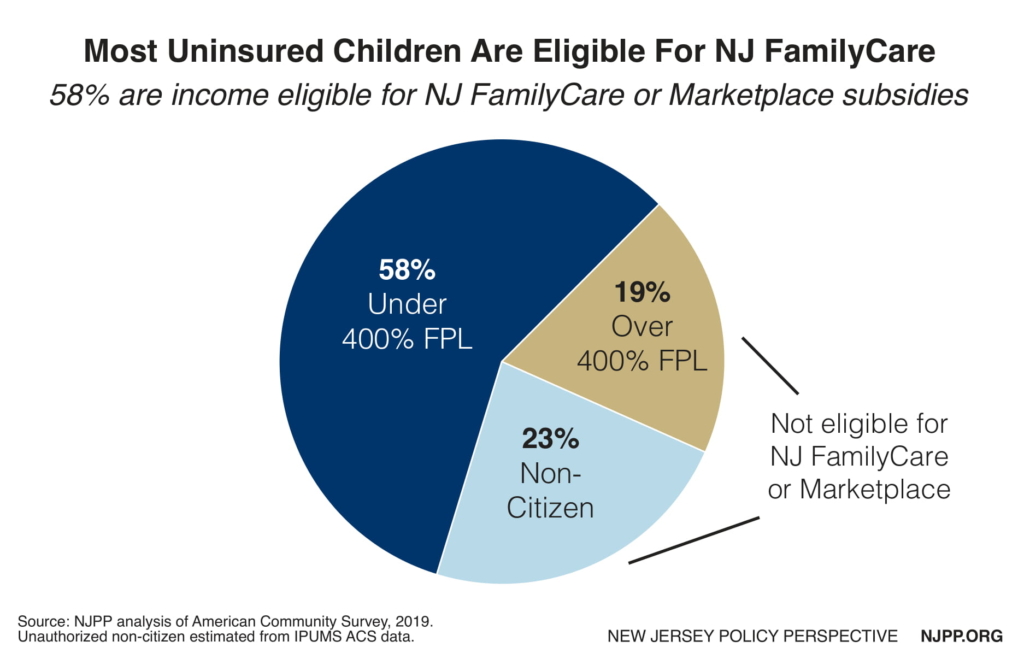

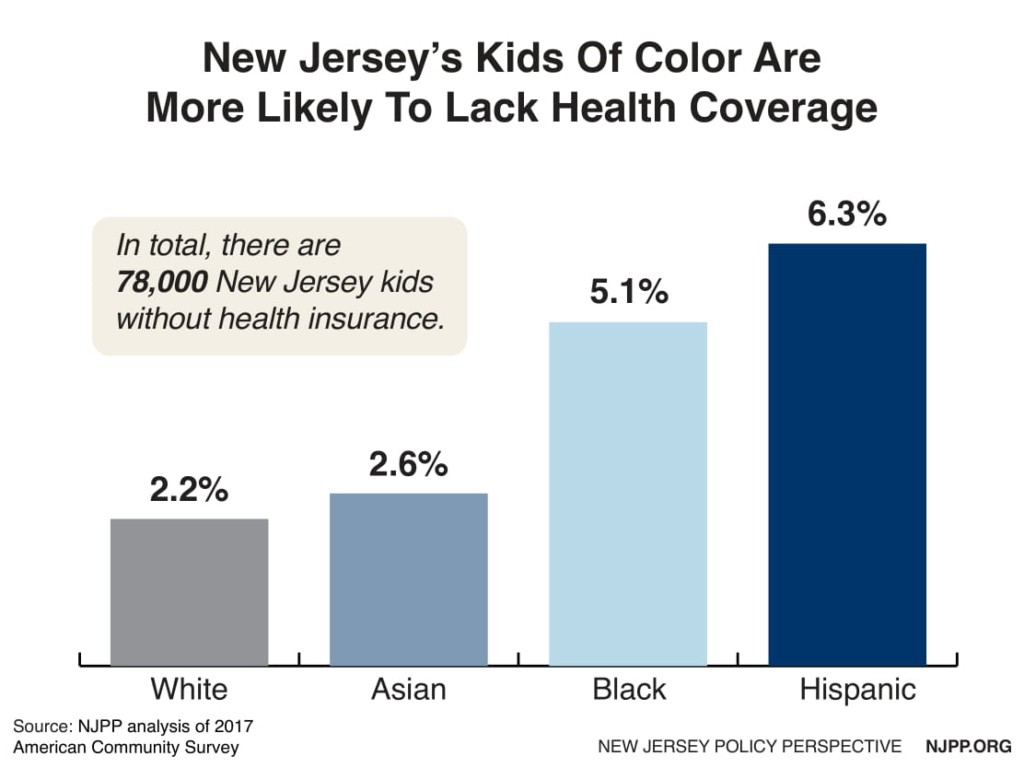

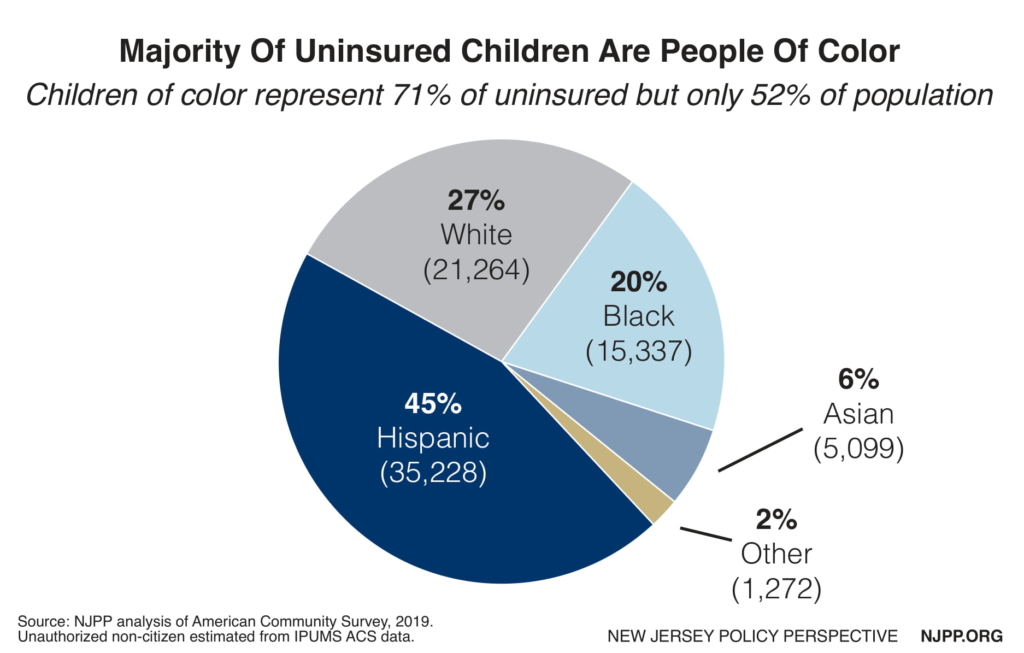

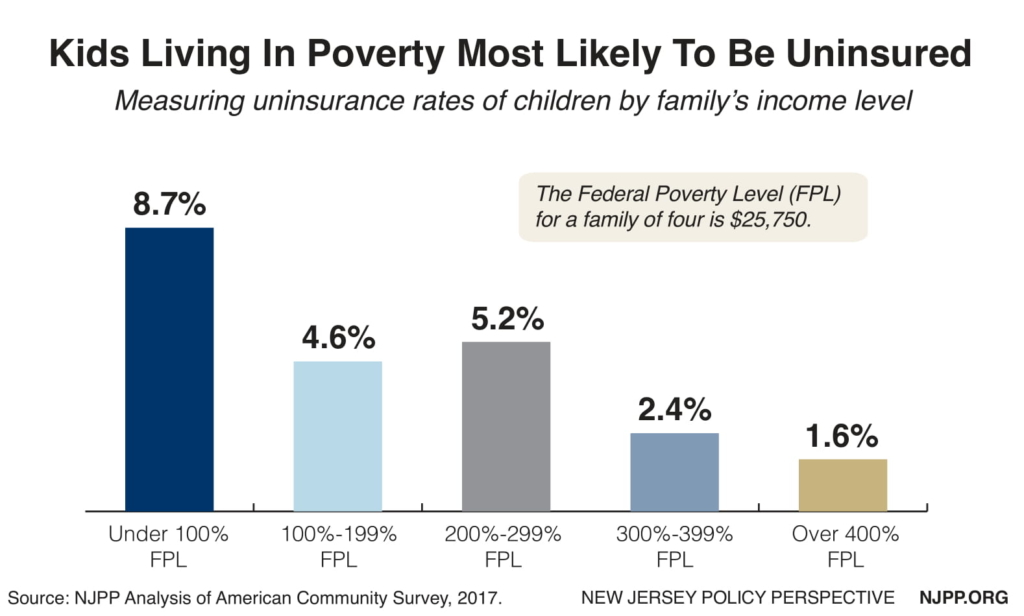

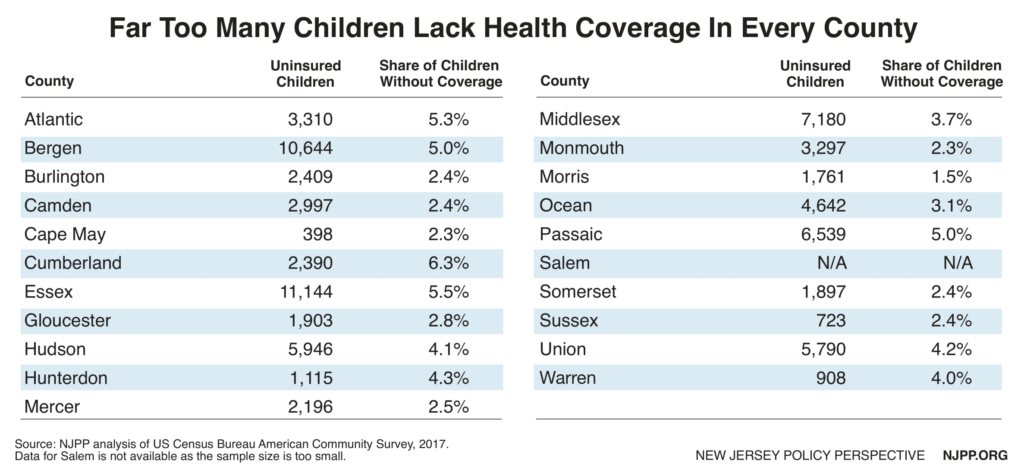

While the Garden State has made great strides in reducing the overall uninsurance rate for children to 3.5 percent, there are still 70,000 kids who remain uninsured. Half of these children are undocumented immigrants not eligible for coverage through NJ FamilyCare, the state Medicaid program. Making the well-being of all children a priority would provide long-range health and social savings to the state. Children who are covered by Medicaid are more likely to do better in school, finish high school, attend college and graduate from college, have fewer emergency-room visits and hospitalizations, and earn more as adults.[48]

New Jersey would also benefit in the long run if undocumented immigrant adults also became eligible for health care coverage, starting with those who can become pregnant. Currently, undocumented women—including DACA recipients and women who have held lawful permanent resident status for less than five years—have no access to health care coverage including coverage for preventative reproductive health services. New Jersey should extend health coverage for all undocumented women by offering a full range of reproductive health services. Modeled after Oregon’s Reproductive Health Equity Act, this comprehensive measure would provide undocumented individuals with health care coverage for contraceptives and related services including counseling, voluntary sterilization, screenings for pregnancy, pregnancy care, birth services, sexually-transmitted infections and cancers, and abortion care.[49]

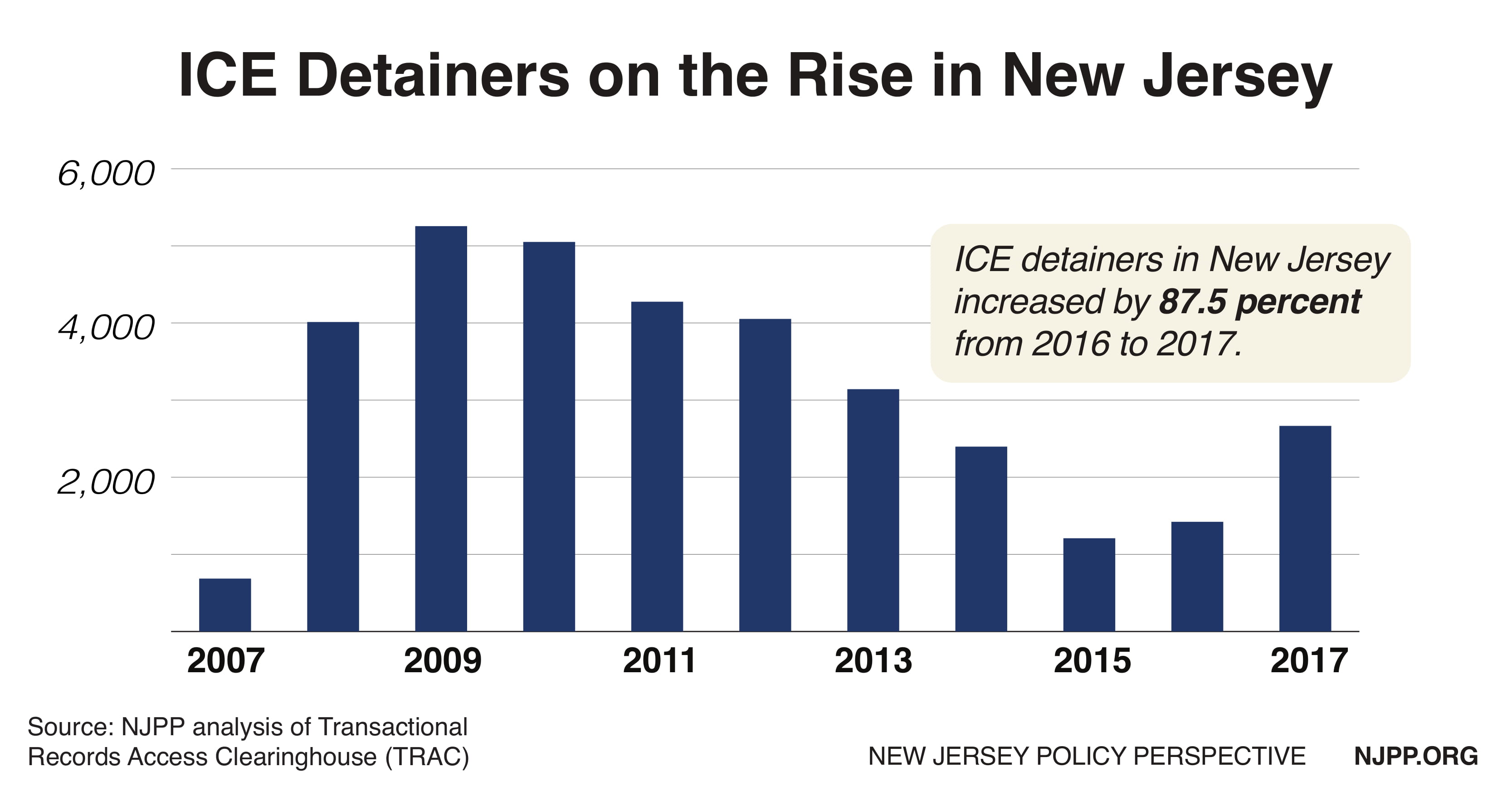

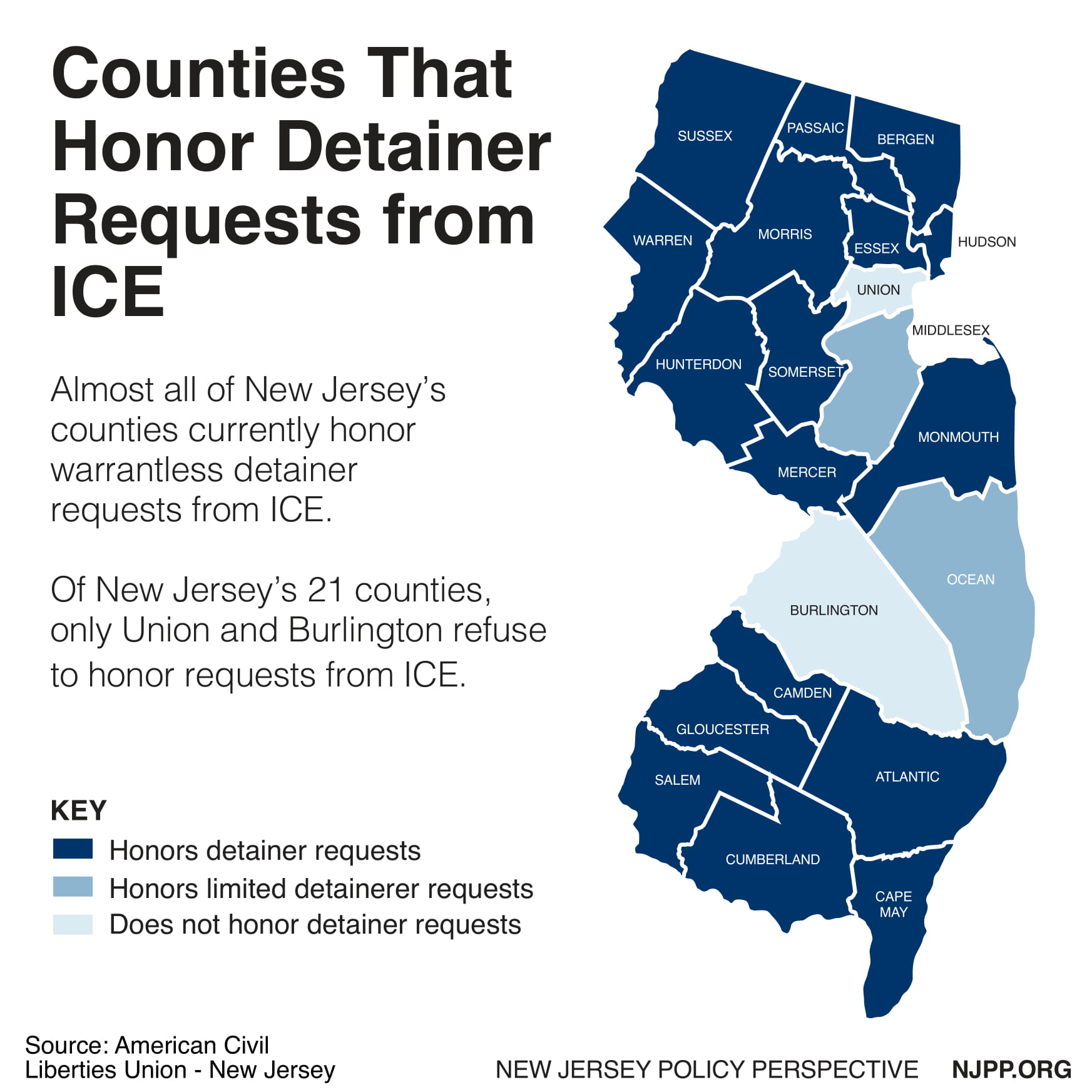

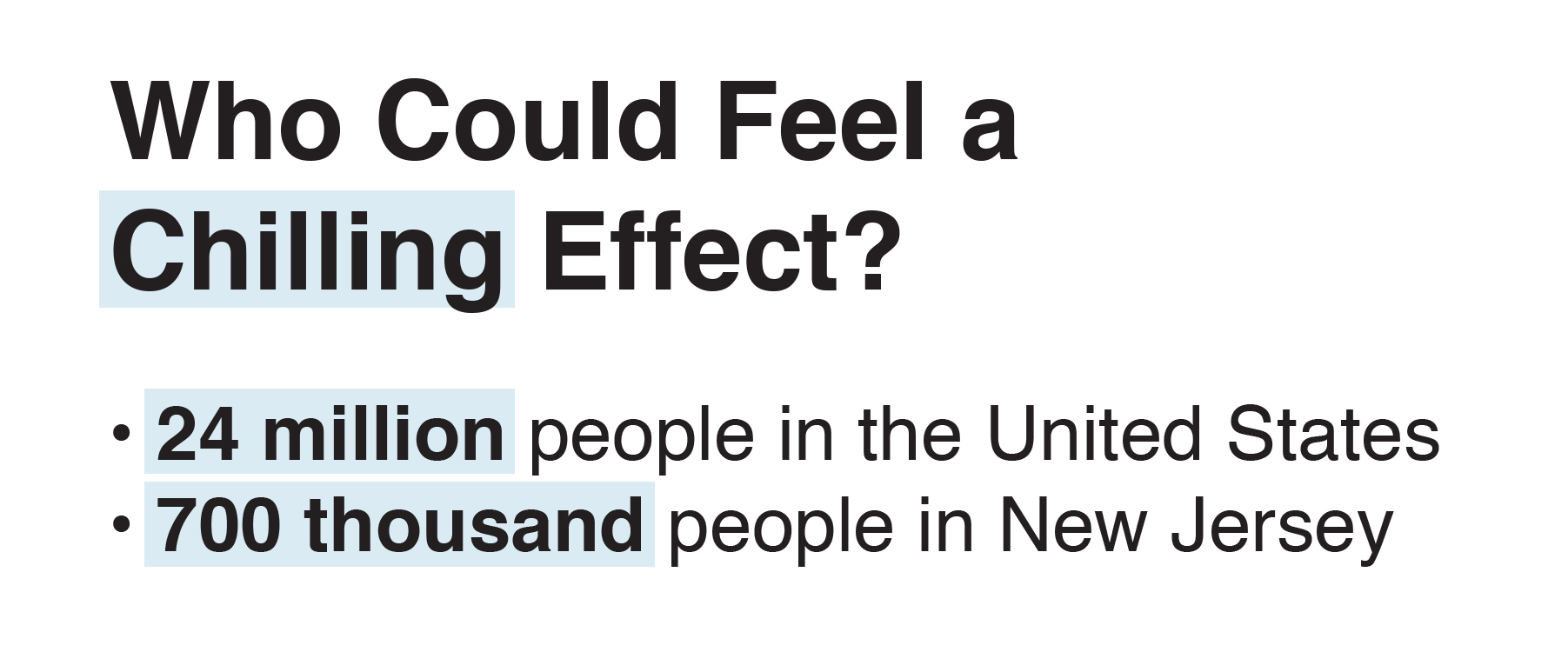

In addition to expanding Medicaid coverage, policymakers should address additional barriers to health care that undocumented families face every day. For example, immigrant rights advocates are pushing to join the 12 states and DC that already allow all residents to obtain a driver’s license, regardless of immigration status.[50] Though seemingly unrelated, expanding eligibility to a driver’s license to all qualified individuals in the state would profoundly improve the ability to access to health care. Transportation barriers created by the inability to access a driver’s license and fear of being detained at a routine traffic stop equate to real obstacles for undocumented people, missed doctor’s appointments and delays in picking up prescriptions. The outcomes have negative health implication and are especially detrimental for time-sensitive, pregnancy related care.[51] Transportation barriers are particularly harmful for those with lower incomes or those who are underinsured or uninsured.

Special Thanks To:

Cherry Hill Women’s Center

Planned Parenthood Action Fund of New Jersey

New Jersey Institute for Social Justice

National Immigration Law Center

Garden State Equality

Rutgers Criminal and Youth Justice Clinic

Women Who Never Give Up

National Council of Jewish Women – Essex County

American Friends Service Committee Prison Watch

New Jersey Family Planning League

Family Planning Association of New Jersey

American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey

New Jersey Abortion Access Fund

Unitarian Universalist Faith Action New Jersey

National Institute for Reproductive Health

State Innovation Exchange

Appendix I: Reproductive Justice Definition and Resources

Reproductive Justice is both a theoretical framework and a social movement created by women of color in the Southern United States as an alternative to the mainstream reproductive rights movement. Sister Song describes Reproductive Justice as the complete physical, mental, spiritual, political, social, and economic well-being of individuals, based on the full achievement and protection of human rights.[52] The issues central to Reproductive Justice impact one’s right “to not have children using safe birth control, abortion, or abstinence; the right to have children under the conditions we choose; and the right to parent the children we have in safe and healthy environments.”[53] By centering the unique, interconnected identities that shape the lives of women within the movement, organizations using the Reproductive Justice framework present a holistic vision with which to challenge policy decisions entrenched in reproductive oppression.

By placing bodily autonomy and the right to access abortion care within the larger human rights framework, Reproductive Justice illuminates the intersections of seemingly unrelated issues like police violence, inhumane immigration policies and environmental racism.

The concept, in part, grew out of the acknowledgment that communities of color and other marginalized groups were often left out of reproductive rights advocacy work, which traditionally centers on abortion rights. This limited scope fails to account for the historical reproductive oppression of people of color engrained in the United States, including forced sterilization, medical experimentation, and family separation. By framing reproductive rights around the issues of “choice” and “privacy,” the mainstream movement for reproductive freedoms have effectively silenced the voices, experiences, and circumstances of women who historically have had to contend with racial and economic injustice. For example, shortly after Roe v. Wadewas decided in 1973, Congress quickly passed the Hyde Amendment, banning federal dollars from being used to provide abortion care. The failure of reproductive rights advocates to immediately mobilize against this policy has had a devastating and long-lasting effect on access to abortion care for poor women. Despite a 1993 modification that extended coverage in cases of rape, incest, or danger to the mother’s life, the Hyde Amendment remains a major barrier to abortion care, especially for women of color and immigrants.

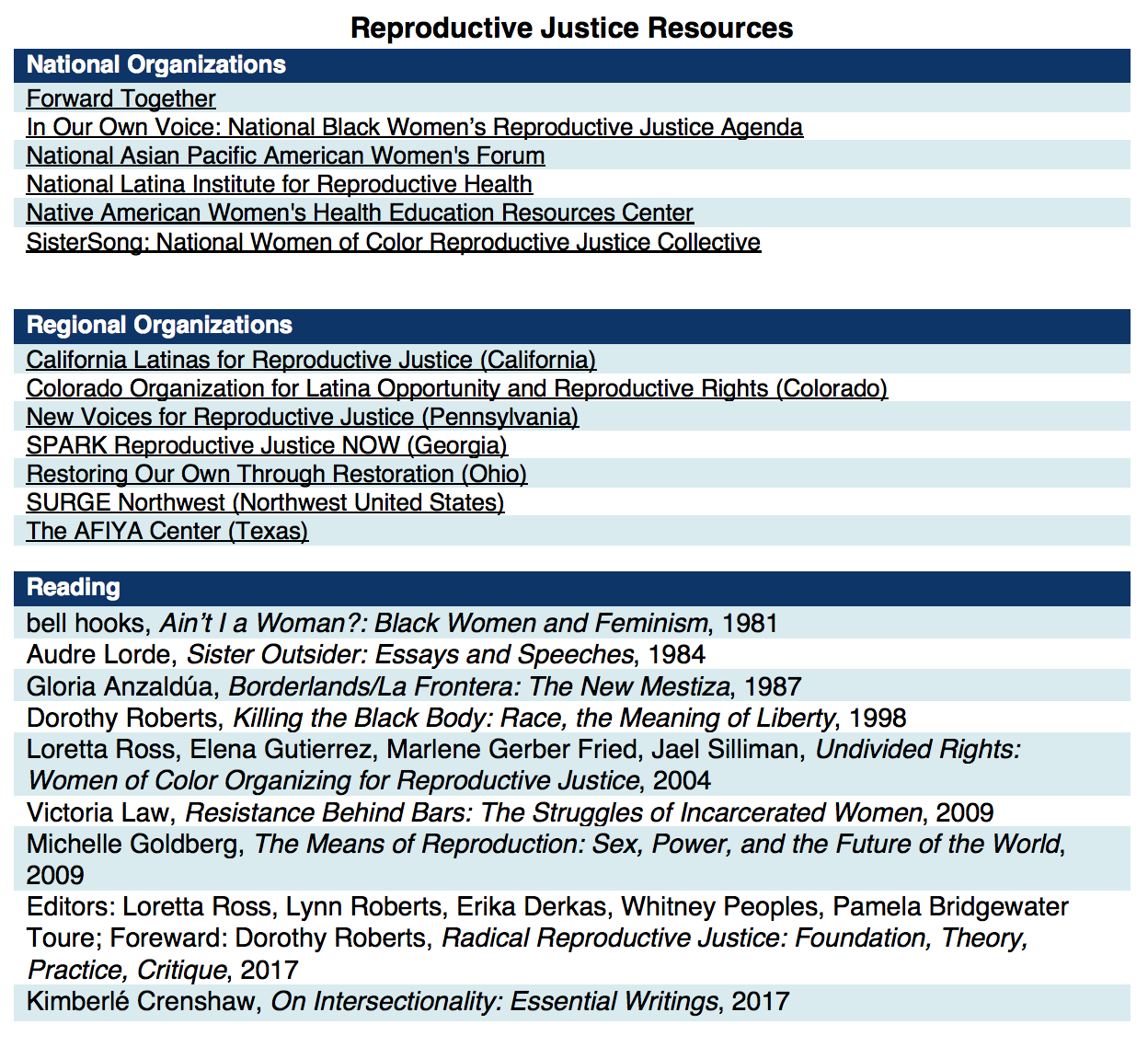

For more information, we encourage you to look to the Reproductive Justice organizations led by people of color advancing policy campaigns that reflect the unique needs of their communities and the historical work of Reproductive Justice leaders.

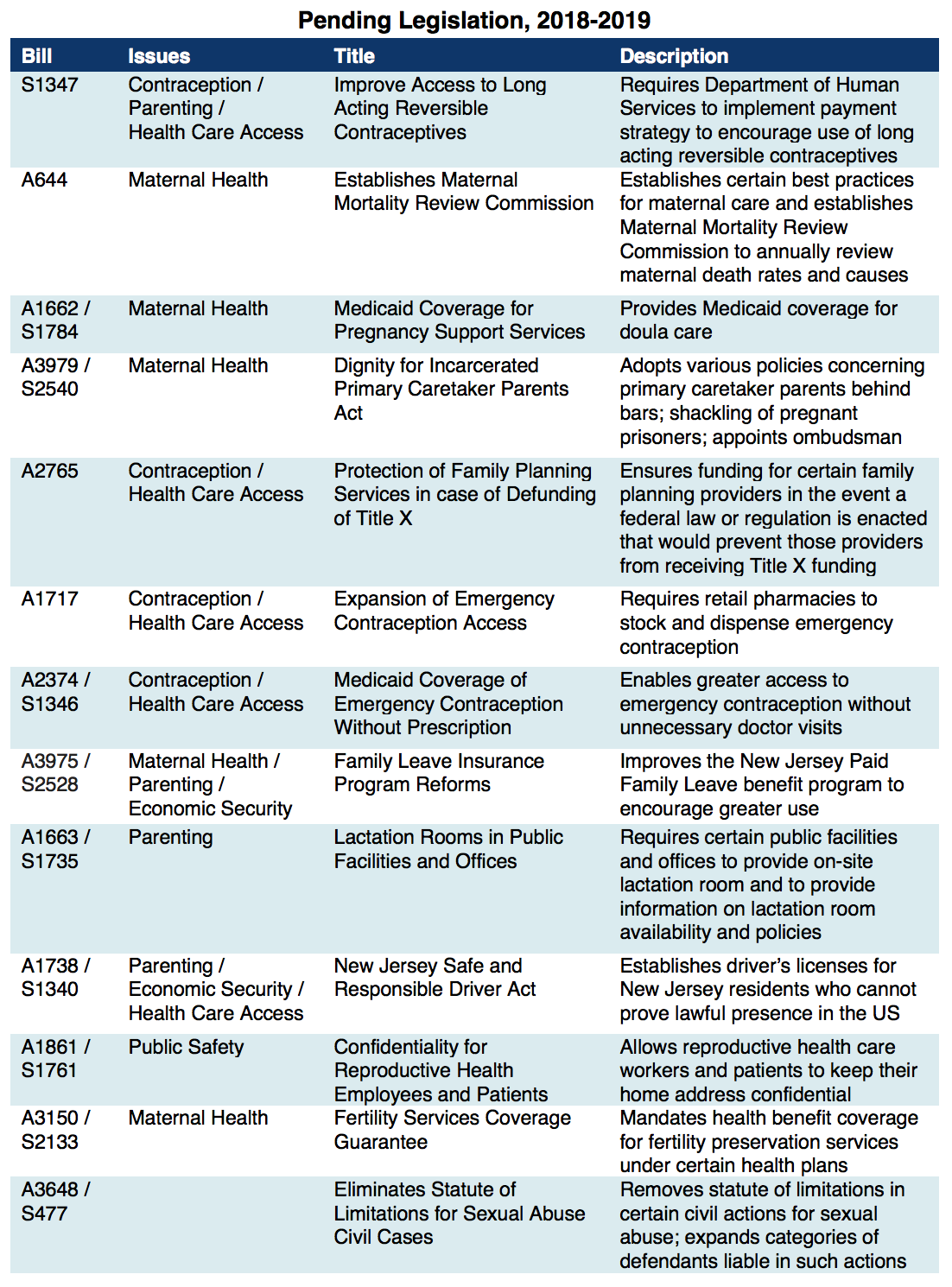

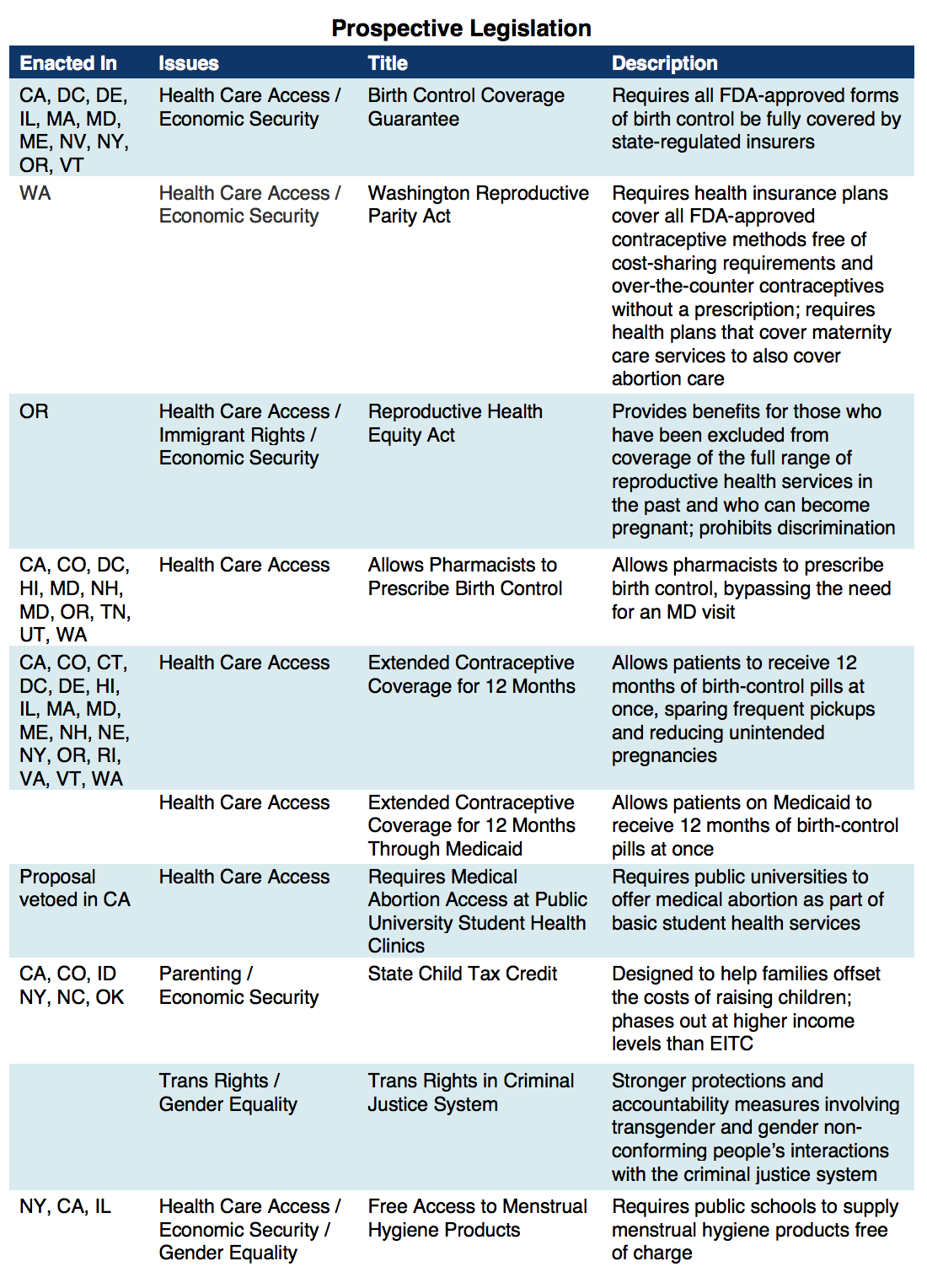

Appendix II: Recent and Pending Legislation in New Jersey That Reflect a Reproductive Justice Framework

Endnotes

[1] In this report, low-income generally refers to those with incomes at 200 percent or less of the federal poverty guidelines which in 2018 is just over $50,000 per year for a family of four.

[2] NJ.com, Eliminated by Christie 8 Years Ago, $7.5M for Women’s Clinics is Making a Comeback, January 2017. http://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2018/01/eliminated_by_christie_8_years_ago_75m_for_womens.html

[3] Last year 94 percent of those seeking care at family planning clinics had incomes at 200% or less of the federal poverty guidelines (Interview with New Jersey Family Planning League).

[4] P.L.2017, Chapter 50, An Act Establishing a Home Visitation Pilot Program in Medicaid, Approved May 1, 2017. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/AL17/50_.PDF

[5] New Jersey Department of Health, DOH Announces $4.3 million to Reduce Disparities in Birth Outcomes and Black Infant Mortality, April 2018. https://nj.gov/governor/news/news/562018/approved/20180430a_birthoutcomes.shtml

[6] AMA Journal of Ethics, “Vulnerable” Populations: Medicine, Race, and Presumptions of Identity, July 2011. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/vulnerable-populations-medicine-race-and-presumptions-identity/2011-07

[7] Guttmacher Institute, State Facts About Unintended Pregnancy: New Jersey, August 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/state-facts-about-unintended-pregnancy-new-jersey

[8] Obstetrics & Gynecology, Number of Oral Contraceptive Pill Packages Dispensed and Subsequent Unintended Pregnancies, March 2011. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2011/03000/Number_of_Oral_Contraceptive_Pill_Packages.8.aspx

[9] California, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, and Vermont. Colorado, Maine, Oregon and Washington State laws go into effect January 2019. Guttmacher Institute, Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives, August 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/insurance-coverage-contraceptives

[10] New Jersey Department of Human Services, Division of Medical Assistance & Health Services, NJ FamilyCare Coverage of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Devices, Newsletter Volume 28 No. 18, October 2018. https://www.njmmis.com/documentDownload.aspx?fileType=RecentNewsLetters

[11] Emergency contraception is not a medical abortion. Emergency contraception works primarily by delaying or inhibiting ovulation. Emergency contraception will not work if a woman is already pregnant. For more information about the difference between these two medications, see this fact sheet from the American Society for Emergency Contraception http://www.cecinfo.org/custom-content/uploads/2013/03/MedAbort_FactSheet_2013_ASEC.pdf

[12] Guttmacher Institute, Last Five Years Account for More Than One-quarter of All Abortion Restrictions Enacted Since Roe, January 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2016/01/last-five-years-account-more-one-quarter-all-abortion-restrictions-enacted-roe

[13] See Planned Parenthood of Cent. New Jersey v. Farmer, 165 N.J. 609, 629, 762 A.2d 620, 631 (2000) (“The language of that paragraph is ‘more expansive … than that of the United States Constitution….,’ it incorporates within its terms the right of privacy and its concomitant rights, including a woman’s right to make certain fundamental choices. Thus, in New Jersey, we have a long-standing history that begins even prior to Roe v. Wade, demonstrating a commitment to the protection of individual rights under the State Constitution.”) (citations omitted); id. at 632-33 (“Our inquiry begins with an examination of the nature of the affected right. We have earlier discussed the importance of a woman’s right to control her body and her future, a right we as a society consider fundamental to individual liberty. Although we will not repeat that discussion here, we are keenly aware of the principle of individual autonomy that lies at the heart of a woman’s right to make reproductive decisions and of the strength of that principle as embodied in our own Constitution. We have not hesitated, in an appropriate case, to read the broad language of Article I, paragraph 1, to provide greater rights than its federal counterpart. Our precedents make clear that the classification created by the statute is deserving of the most exacting scrutiny.”) (citations omitted).

[14] Women’s Health Issues, At What Cost? Payment for Abortion Care by U.S. Women, May-June 2013. https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(13)00022-4/fulltext

[15] New York Times, ’70 Abortion Law: New York Said Yes, Stunning the Nation,April 2000. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/04/09/nyregion/70-abortion-law-new-york-said-yes-stunning-the-nation.html

[16] Guttmacher Institute, Characteristics of U.S. Abortion Patients in 2014 and Changes Since 2008, 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/characteristics-us-abortion-patients-2014

[17] National Abortion Federation, 2017 Violence and Disruption Statistics, 2017. https://5aa1b2xfmfh2e2mk03kk8rsx-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017-NAF-Violence-and-Disruption-Statistics.pdf

[18] Guttmacher Institute, Assessing the Gap Between the Cost of Care for Title X Family Planning Providers and Reimbursement from Medicaid and Private Insurance, January 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pubs/Title-X-reimbursement-gaps.pdf

[19] NARAL Pro-Choice America, The Truth about Crisis Pregnancy Centers, January 2017. https://www.prochoiceamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/6.-The-Truth-About-Crisis-Pregnancy-Centers.pdf

[20] Ibid 19

[21] Ibid 19

[22] Blue Jersey, Crisis Pregnancy Centers Are in Our Schools, Teaching Our Children, April 2018. http://www.bluejersey.com/2018/04/crisis-pregnancy-centers-are-in-our-schools-teaching-our-children/

[23] Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, State Profiles Fiscal Year 2017: New Jersey, July 2018. https://siecus.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NEW-JERSEY-FY17-FINAL-New.pdf

[24] Although this paper seeks to include all those who can become pregnant, including women, transgender men, and gender non-conforming people, fake women’s health centers only target those they perceive to experience pregnancy, namely cisgender women.

[25] AMA Journal of Ethics, Why Crisis Pregnancy Centers Are Legal but Unethical, March 2018. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/why-crisis-pregnancy-centers-are-legal-unethical/2018-03

[26] Guttmacher Institute, State Facts About Abortion: New Jersey, May 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/state-facts-about-abortion-new-jersey#7

[27] NJ Spotlight, Black Mamas Highlight Racial Maternal Health Disparities, April 2018. http://www.njspotlight.com/stories/18/04/24/black-mamas-highlight-racial-maternal-health-disparities/

[28] NJ Spotlight, Racial Disparity in Infant Mortality Remains Persistent Public Health Challenge, June 2017. http://www.njspotlight.com/stories/17/06/05/racial-disparity-in-infant-mortality-remains-persistent-public-health-challenge/

[29] Human Nature, Do US Black Women Experience Stress-Related Accelerated Biological Aging? A Novel Theory and First Population-Based Test of Black-White Differences in Telomere Length, March 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2861506/

[30] Journal of Women’s Health, The Impact of Racism on the Sexual and Reproductive Health of African American Women, July 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4939479/

[31] Vox.com, Black Moms Die in Childbirth 3 Times as Often as White Moms. Except in North Carolina, July 2017. https://www.vox.com/health-care/2017/7/3/15886892/black-white-moms-die-childbirth-north-carolina-less

[32] Texas A&M University, Why American Infant Mortality Rates are So High, October 2016. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/10/161013103132.htm

[33] NJ Department of Health and The Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (NJ PRAMS), Employment, Workplace Leave and Return to Work Among New Jersey Mothers, March 2018. https://www.nj.gov/health/fhs/maternalchild/documents/workforce_mar2018.pdf

[34] Ibid 33

[35] Choices in Childbirth, Overdue: Medicaid and Private Insurance Coverage of Doula Care to Strengthen Maternal and Infant Health, January 2016.https://choicesinchildbirth.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/DoulaBrief_FINAL_1.4.16.pdf

[36] Ibid 35

[37] Ibid 35

[38] Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2000, 2015 in The Sentencing Project, Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons, 2016. http://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

[39] The Sentencing Project, Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons, 2016. http://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

[40] NJ.com, Sex Abuse Scandal at N.J. Women’s Prison Keeps Getting Worse, July 2018. https://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2018/07/sex_abuse_scandal_at_nj_womens_has_sparked_at_leas.html

[40] Vera Institute of Justice, Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform, August 2016. https://www.vera.org/publications/overlooked-women-and-jails-report

[41] NJ.com, Locked Up, Fighting Back: More Than a Dozen Female Inmates Accused an Officer of Abuse, January 2017. https://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/page/locked_up.html

[42] NJ.com, New Crackdown on N.J.’s Women’s Prison Pushed Amid Sex Abuse Claims, May 2018. https://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2018/05/lawmakers_push_crackdown_on_nj_womens_prison_amid.html

[43] National Immigration Law Center, Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs,December 2015. https://www.nilc.org/issues/economic-support/overview-immeligfedprograms/

[44] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Summary of Immigrant Eligibility Restrictions Under Current Law, February 2009. https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/summary-immigrant-eligibility-restrictions-under-current-law#sec

[45] States with health plan that cover all children include Washington, Oregon, California, Illinois, New York and Massachusetts.

[46] National Immigration Law Center, Health Coverage Maps, January 2018. https://www.nilc.org/issues/health-care/healthcoveragemaps/

[47] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Medicaid Helps Schools Help Children, April 2017. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-helps-schools-help-children

[48] Reproductive Health Equity Act (OR HB 3391), 2017. https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2017R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/HB3391

[49] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Let’s Drive New Jersey: Expanding Access to Driver’s Licenses is a Common-Sense Step in the Right Direction, January 2018. https://www.njpp.org/reports/lets-drive-new-jersey-expanding-access-to-drivers-licenses-is-a-common-sense-step-in-the-right-direction

[50] The Journal of Rural Health, Access to Transportation and Health Care Utilization in a Rural Region, Winter 2005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15667007

[51] SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective and the Pro-Choice Public Education Project, Reproductive Justice Briefing Book: A Primer on Reproductive Justice & Social Change, 2007. https://www.law.berkeley.edu/php-programs/courses/fileDL.php?fID=4051

[52] Ross, Roberts, Derkas, Peoples, Bridgewater Toure, Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique, November 2017.

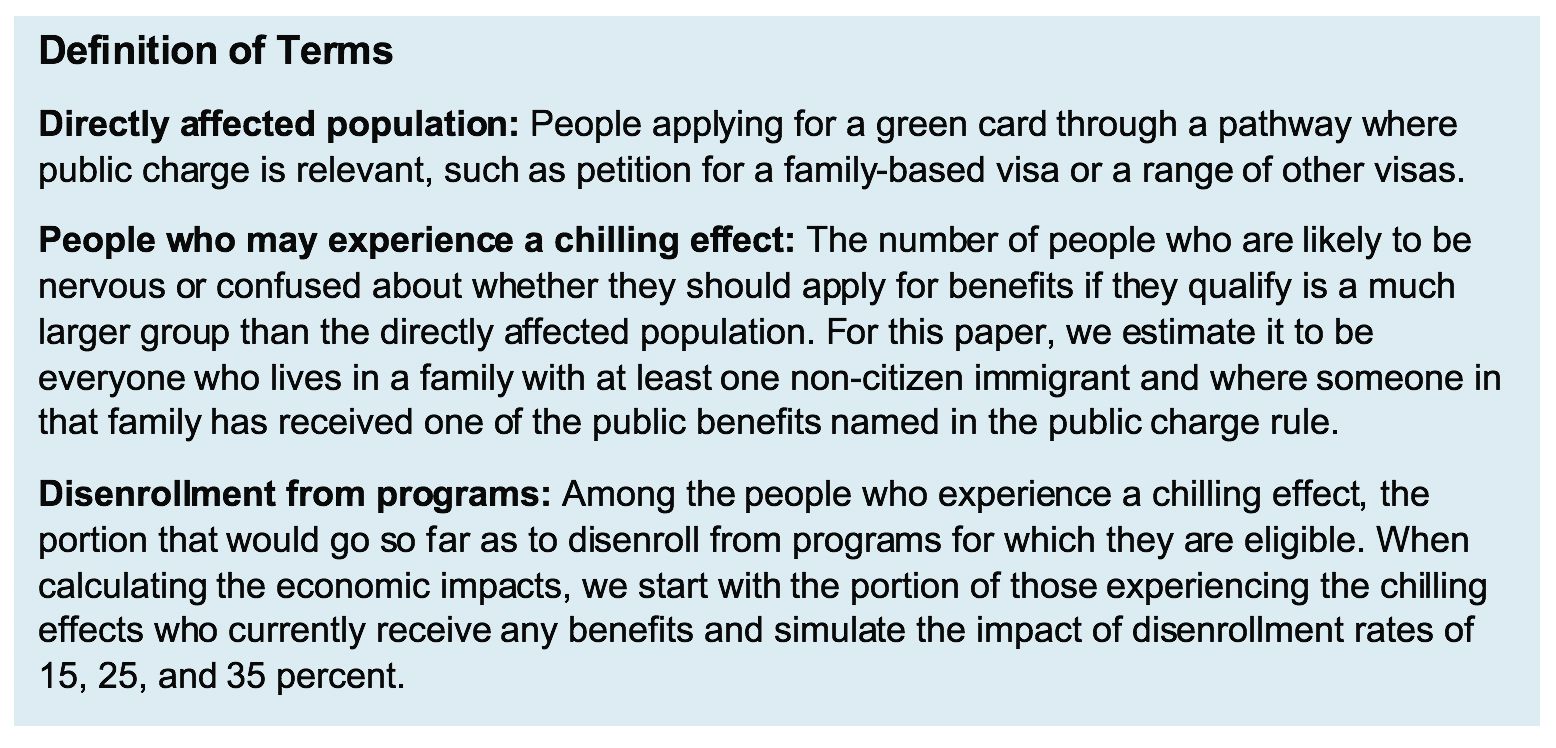

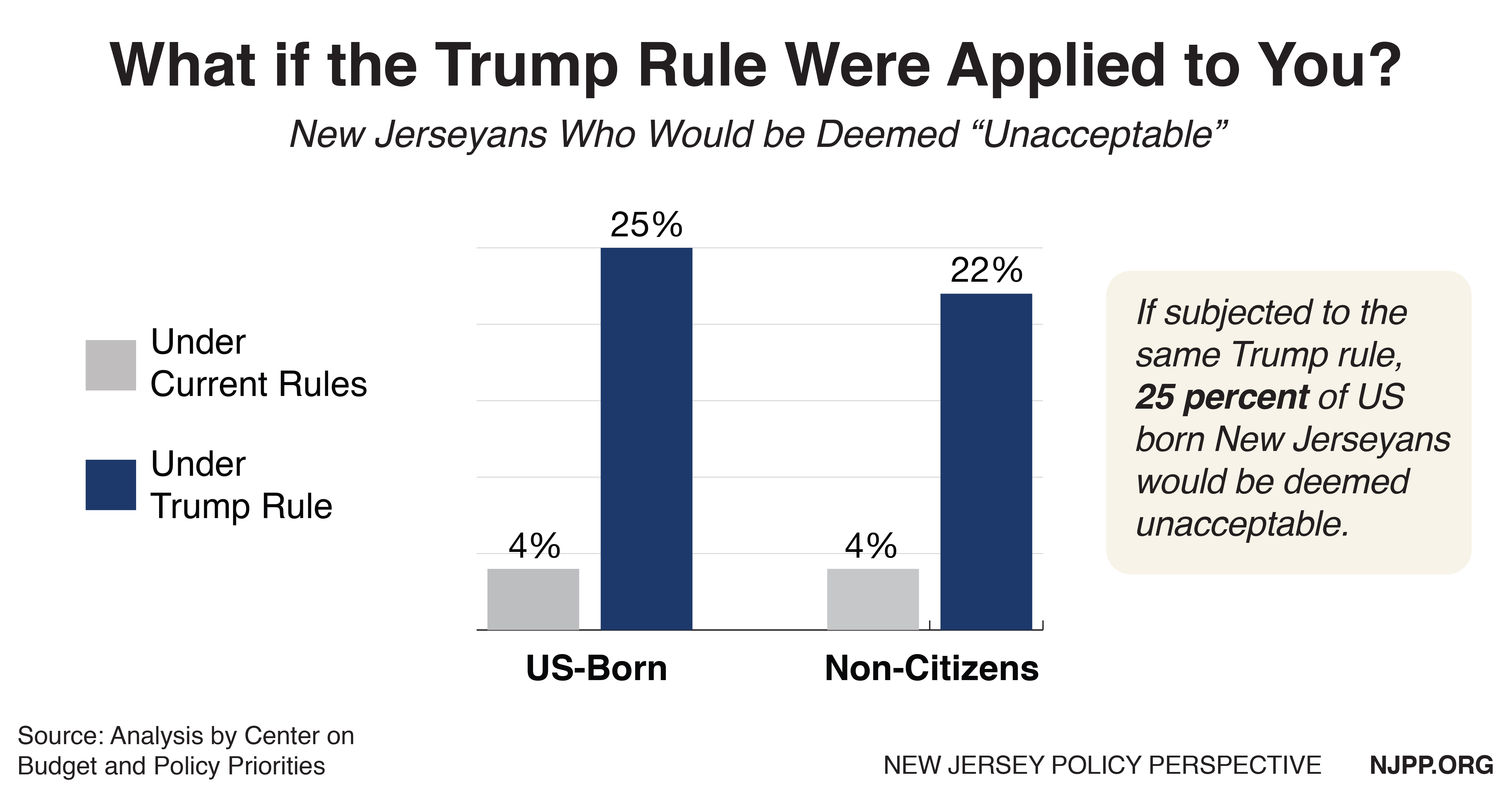

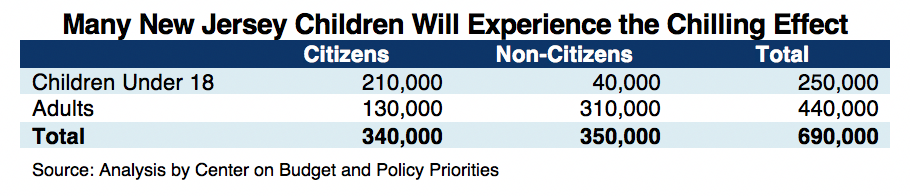

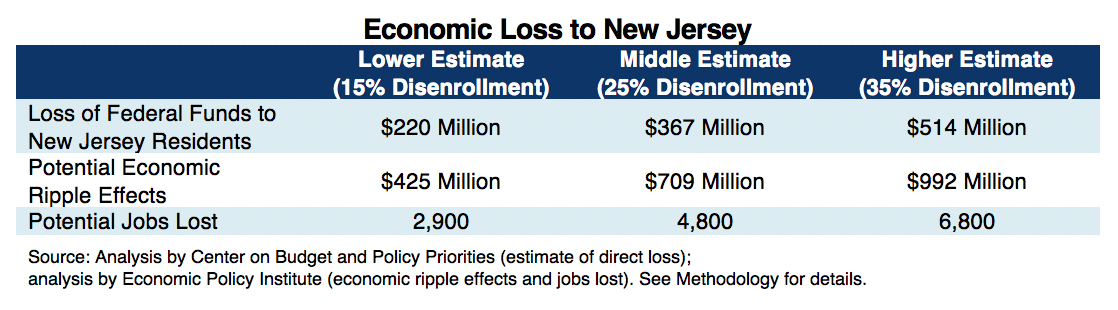

The direct effect of the Trump Rule would fall primarily on people applying for a green card through a family-based petition,where public charge is relevant. Similar standards would also apply to people seeking to extend or change their temporary non-immigrant status in the United States. The rule change would likely lead to the denial of green cards to hundreds of thousands of otherwise eligible applicants for family-based and employment visas.

The direct effect of the Trump Rule would fall primarily on people applying for a green card through a family-based petition,where public charge is relevant. Similar standards would also apply to people seeking to extend or change their temporary non-immigrant status in the United States. The rule change would likely lead to the denial of green cards to hundreds of thousands of otherwise eligible applicants for family-based and employment visas.