To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

New Jerseyans born outside of the United States – both documented and undocumented – make up more than a fifth of the state’s population and are an enormous benefit to New Jersey’s economy and culture. Now, almost two years into the Trump administration, undocumented immigrants who have been living productive lives in the Garden State are at increased risk of being detained and deported by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), sometimes with the help of local law enforcement.

When immigrants come in contact with local and state law enforcement agencies, it is standard practice for their information to be shared with federal authorities at the FBI and ICE. This practice is known as “Secure Communities.”[1] ICE can then request a “detainer hold,” which asks the local or state law enforcement agency to detain an immigrant for up to 48 hours beyond their release date. If local and state law enforcement choose to honor the request, ICE does not guarantee that it will pick up the detained individuals.

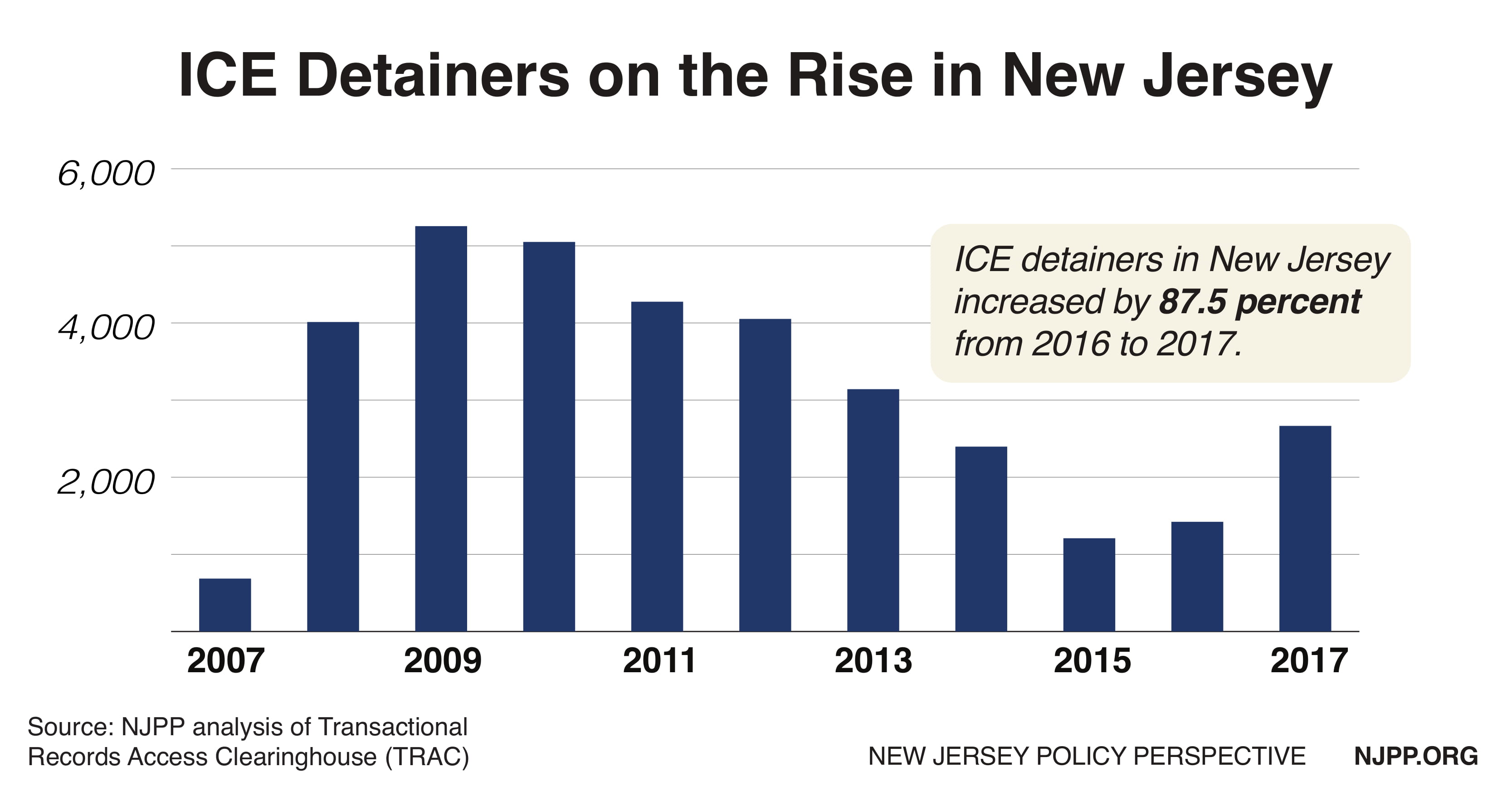

After peaking in 2009, ICE detainers in New Jersey steadily declined through 2015, but they are increasing under the Trump administration. From 2016 to 2017, ICE’s issuance of detainers has increased by 87.5 percent in New Jersey, compared to 40 percent nationally.[2] New Jersey has voluntarily honored these detainer requests, or “immigration holds,” at least 63 percent of the time,[3] compared to 54 percent nationwide.[4] By honoring detainers, New Jersey allows ICE to use local resources, without bearing any of the cost, to imprison people without due process. In many cases immigrants are held without any charges pending. These detainers come with a significant cost – both social and in real dollars – to New Jersey.

New Jersey’s local law enforcement has paid at least $12 million to voluntarily honor ICE detainer requests and hold immigrants in police facilities and jails.[5] This calculation assumes that immigrants were detained for the legally allowed 48 hours, when in reality most were held much longer. It is estimated that, on average, immigrants on detainer holds are incarcerated for twenty-four days past their release date, translating to a total cost of $139 million to local law enforcement over the last decade.

In the same time period, people who have been detained, and by extension their families and the broader economy, have forgone $5 million in lost wages.[6] This is part of the human cost associated with immigration holds; families with immigrants suffer from lost wages, businesses lose customers, employers have to bear the costs associated with employee turnover, and children of detainees are saddled with the emotional burden of losing a parent.

Further, over 34,000 immigrants who were issued a detainer were held in police custody for longer than the 48 hours legally permitted. This represents more than 9 in 10 of the 36,290 detainers issued between ICE’s formation in 2003 and April 2018 when the latest data are available. The ramping up of immigration enforcement is also reflected in immigration arrests,[7] which have increased in New Jersey by 43 percent, from 2,315 in 2016 to 3,311 in 2017. This is almost double the national increase of 23 percent.[8]

The AG Directive

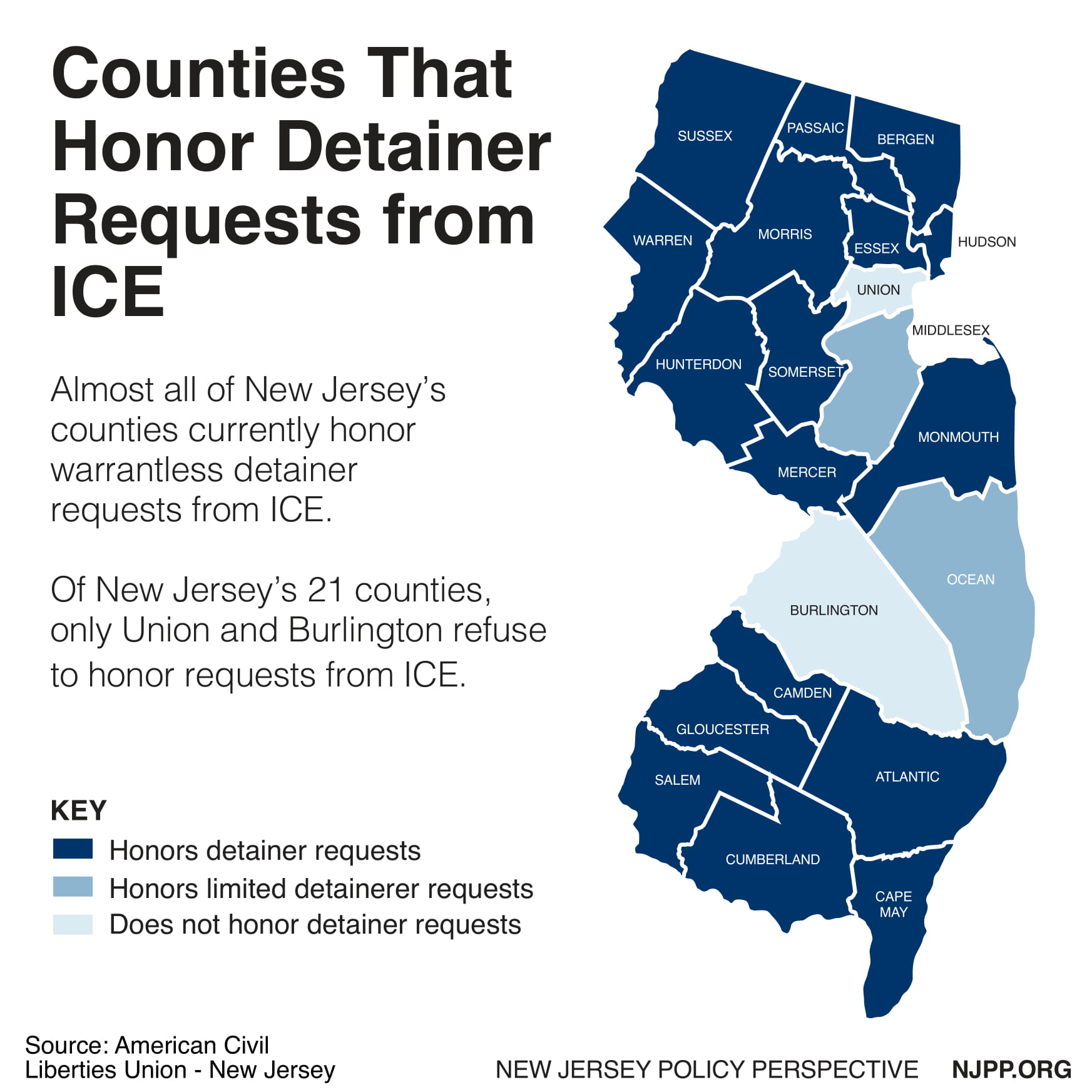

Almost all of New Jersey’s counties – 19 of 21 – honor warrantless detainer requests from ICE.[9] Only two, Burlington and Union, do not. In Middlesex and Ocean Counties, warrantless detainer requests are honored, but only in limited situations. It is important to note, however, that all law enforcement agencies notify ICE of arrests for DUIs and indictable offenses per New Jersey Attorney General Law Enforcement Directive 2007-3 (AG Directive).[10]

The AG Directive was issued under Governor Corzine’s administration by then-New Jersey Attorney General Anne Milgram. The policy outlines how local, county, and state police should interact with individuals who they have reason to believe are undocumented immigrants. The directive is notoriously vague, leaving it up to police officers to interpret when, where, and how they question the status of individuals they suspect to be undocumented.

Since 2007, immigrant rights groups have expressed concern that this discretion results in law enforcement infringing on the rights of New Jersey residents. A 2009 study by the Center for Social Justice at Seton Hall University Law School found evidence of “improper police questioning and arrest of the state’s non-criminal Latino drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and commuters.”

A new directive that reigns in how and when local law enforcement interacts with ICE has the potential to make New Jersey safer for all by restoring trust and cooperation with law enforcement in immigrant communities. By entangling police with immigration enforcement, the current system disincentivizes immigrants from reporting crimes or calling 9-1-1 if they are in danger. For taxpayers, a new directive will provide transparency, accountability, and a more responsible use of public funds that promotes safety instead of sowing racial division.

Now, over a decade since the AG Directive was issued, New Jersey has a prime opportunity to adopt a new policy that better reflects the immigration realities under the Trump administration. New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal, appointed only nine months ago, can and should adopt a new directive that recognizes the humanity of all New Jersey residents, ensures due process, and ends the practice of needlessly separating families.

Endnotes

[1] According to United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Secure Communities program, launched as a pilot program towards the end of the Bush administration and was expanded under the Obama administration, the goal was to cover all 3,181 jurisdictions within the nation and it did in 2013.

[2] New Jersey Policy Perspective analysis of Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University on the Latest Data: Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detainers. Data used FY 2016-FY 2017.

[3] Note from TRAC: ICE recorded that the law enforcement agency refused to comply with the ICE I-247 request. TRAC notes that the field ICE uses to track law enforcement agency refusals is not a required field in ICE’s database. Rather, entry of information is optional. The field is used to record a variety of different reasons why ICE “lifted”—that is withdrew—a custody transfer request. These recorded “lift” reasons often disagree with other information ICE records on whether the individual was actually booked into its custody. For example, ICE sometimes records that an agency refused its transfer request even though ICE records it assumed custody of the individual.

[4] New Jersey Policy Perspective analysis of Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University on the Latest Data: Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detainers. Data usedFY 2003 to April 2018.

[5] The total number of detainers from FY 2007-2017 was 31,171; we then multiply the cost per day, per inmate in 2015 from the Vera Institute’s report The Price of Prisons(https://www.vera.org/publications/price-of-prisons-2015-state-spending-trends/price-of-prisons-2015-state-spending-trends/price-of-prisons-2015-state-spending-trends-prison-spending), which calculates that NJ spends an average of $61,603 per inmate or about $169 a day. Then we multiply that by two days held.

[6] The median individual wage for undocumented workers in the United States is $17,400 per year, according to an unpublished estimate from 2016 provided by Robert Warren, derived from his work published by the Center for Migration Studies. We estimate that it is 14% higher for undocumented immigrants in New Jersey, since the average family income for undocumented immigrants is 14 percent higher in New Jersey, according to an analysis by the Migration Policy Institute published by the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy analysis in Undocumented Immigrants’ State and Local Tax Contributions. Thus, we calculate the estimate by multiplying 34,171 (total detainers from FY 2007 to 2017) by $77 (wages lost per day detained) by 2 (days detained).

[7] The data is limited to what ICE refers to as “interior arrests.” According to ICE, the data does not include arrests made by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) when the individual is transferred to ICE for detention and eventual removal.

[8] New Jersey Policy Perspective analysis of Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University on the Latest Data: Immigration and Customs Enforcement Arrest.

[9] Ending Cooperation with Warrantless ICE Detainer Requests.ACLU sent letters to every New Jersey county jail and asked about their detainer policy. (https://www.aclu-nj.org/theissues/immigrantrights/detainer-map)

[10] New Jersey Attorney General Law Enforcement Directive No. 2007-3 (https://www.nj.gov/oag/dcj/directiv.htm)