The millionaires tax will help tackle growing inequality and provide much needed revenue for critical investments in state assets.

In his fiscal year 2020 budget, Governor Murphy has once again proposed a true “millionaires tax” to ensure the richest households in New Jersey pay their fair share in taxes. Raising the marginal income tax rate on annual earnings over $1 million is a fair and modest policy — and it comes at a particularly important time. Income inequality in the United States, and New Jersey, is at a dangerously high level. Disparities between those at the top and everyone else are growing every day as the wealthy and well-connected take advantage of rigged federal and state tax codes to enrich themselves at the expense of others.

Runaway inequality is widely recognized across the political spectrum as one of the defining economic and political issues of our time. And yet, Governor Murphy’s proposal is receiving the cold shoulder from members of the legislature — even among those who voted for the same exact policy five times during the Christie administration. This reluctance to make the tax code fairer persists despite the millionaires tax being incredibly popular with voters; despite the so-called “millionaire tax flight” myth being repeatedly debunked; and despite the serious and almost universally accepted need for increased investments in New Jersey’s critical assets and rainy day fund. But, before we go too far into the politics of the situation, it’s important to lay out the details of what the governor has proposed.

The Millionaires Tax as a Tool to Combat Income Inequality

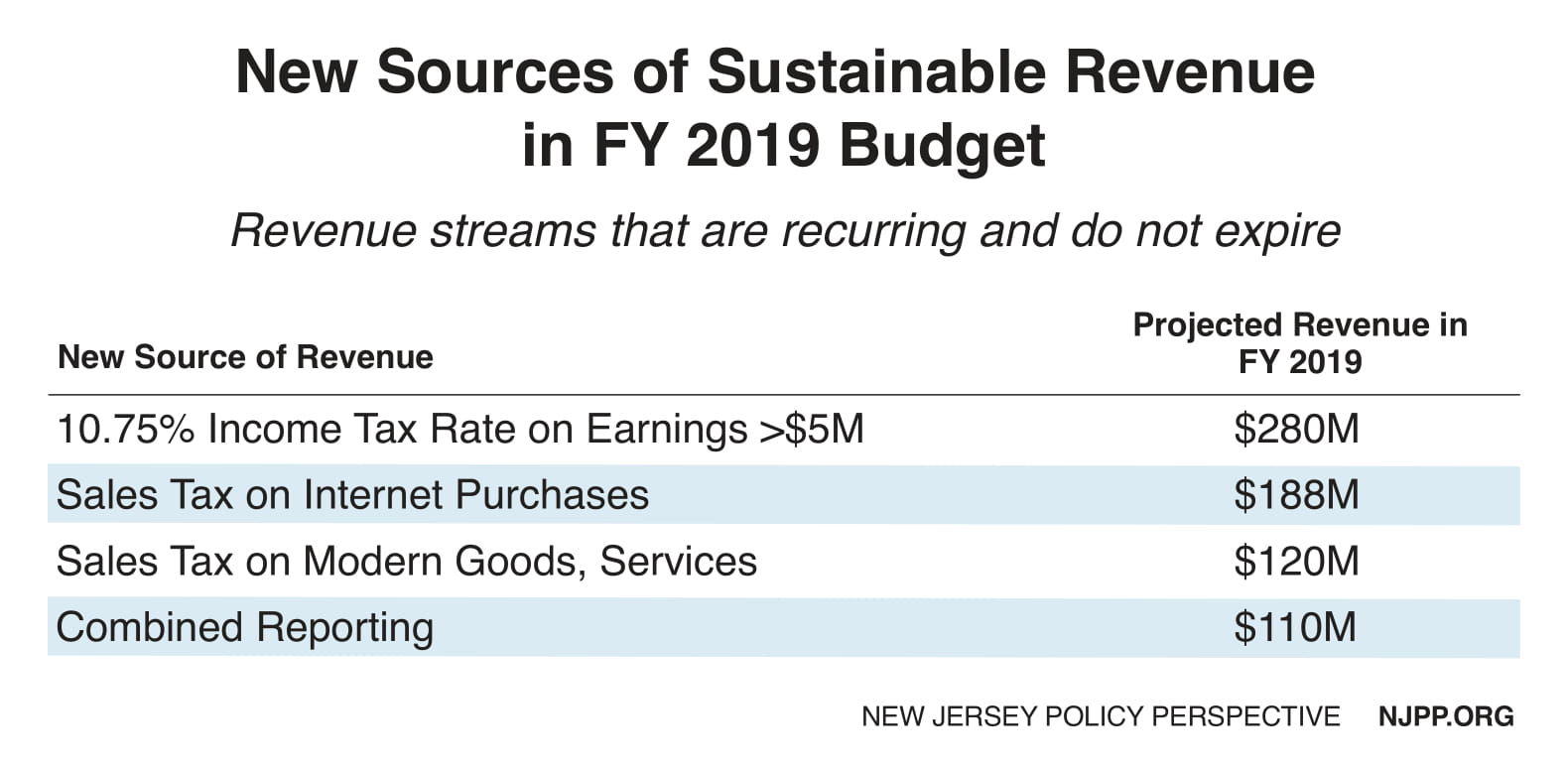

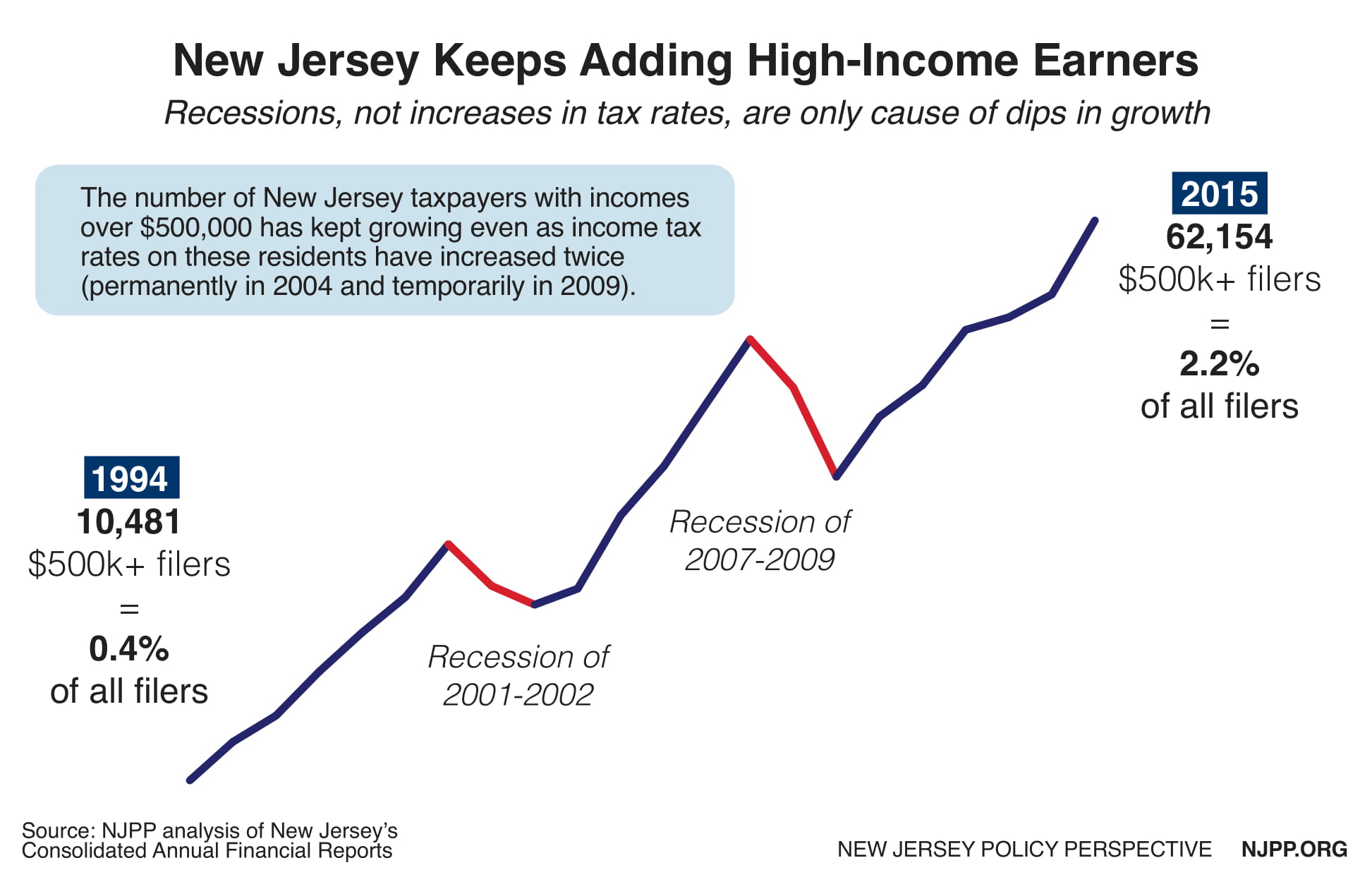

Governor Murphy’s millionaires tax proposal is not a new tax, as it would simply apply the top 10.75 percent income tax rate to all annual earnings over $1 million. Right now, only annual income over $5 million is taxed at this rate, while income between $500,000 and $5 million is taxed at a rate of 8.97 percent. Legislative leaders have already indicated their opposition to a true millionaires tax, claiming it would result in New Jersey’s highest earning families moving to states with lower income tax rates. Given how critical this policy is in mitigating income inequality and fully investing in public programs, services, and infrastructure we all rely on, separating fact from fiction is vital.

First, it’s necessary to note that New Jersey’s income tax is a marginal tax. This means that the 10.75 percent tax rate on people who earn over $5 million doesn’t apply to their entire income — it only applies to earnings over $5 million. All earnings over $500,000 and up to $5 million are taxed at the 8.97 percent rate. Oftentimes, opponents of tax fairness like to confuse the public by implying that the higher tax rate would apply to an individual’s entire income, but that is simply untrue.

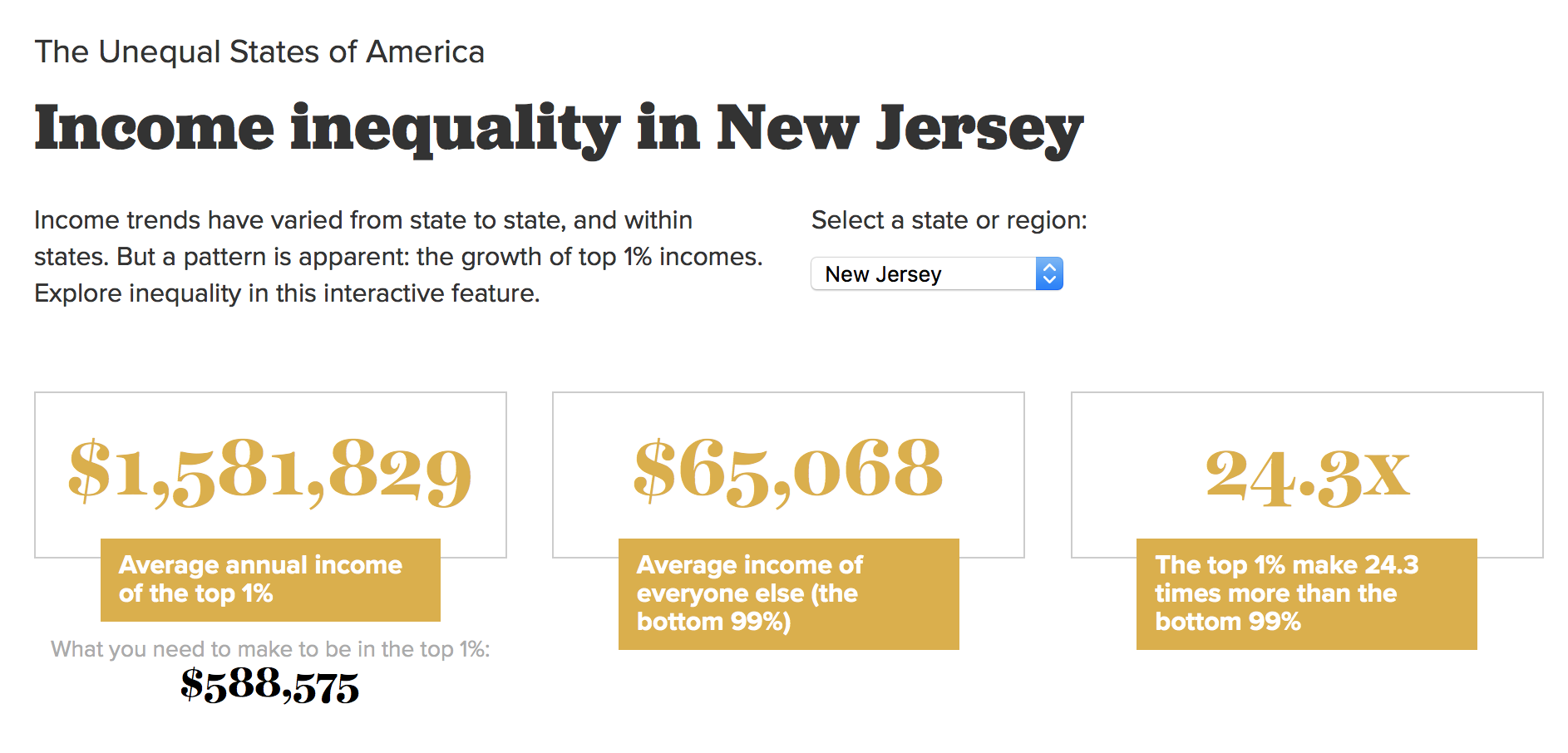

In order to be in the top one percent in New Jersey, you have to make at least $588,575 in annual income. Considering this, millionaires are easily in the top one percent of earners in the Garden State. Compared to the rest of the state — the bottom 99 percent — those in the top one percent are doing exceedingly well. Their average income is $1,581,829, whereas the average income for the bottom 99 percent is $65,068. Simply put, on average the top one percent of New Jerseyans makes 24.3 times more than the bottom 99 percent. This level of inequality ranks New Jersey as 9th worst in the nation.

Source: Economic Policy Institute, The Unequal States of America

Source: Economic Policy Institute, The Unequal States of America

When measuring the collective income of all workers in New Jersey, the top one percent take home nearly one fifth — 19.7 percent — of the entire sum. This is not far off from the state’s historic high, which peaked just before the Great Depression. When economic inequality was at its lowest — between the 1950s and late 1970s — the share of total income that the top one percent of New Jerseyans owned was less than 10 percent. The top one percent owning this much of New Jersey’s total income should act as a bright red flag that inequality is out of control and now is an opportune time to implement measures that promote tax fairness, including the millionaires tax proposed by Governor Murphy.

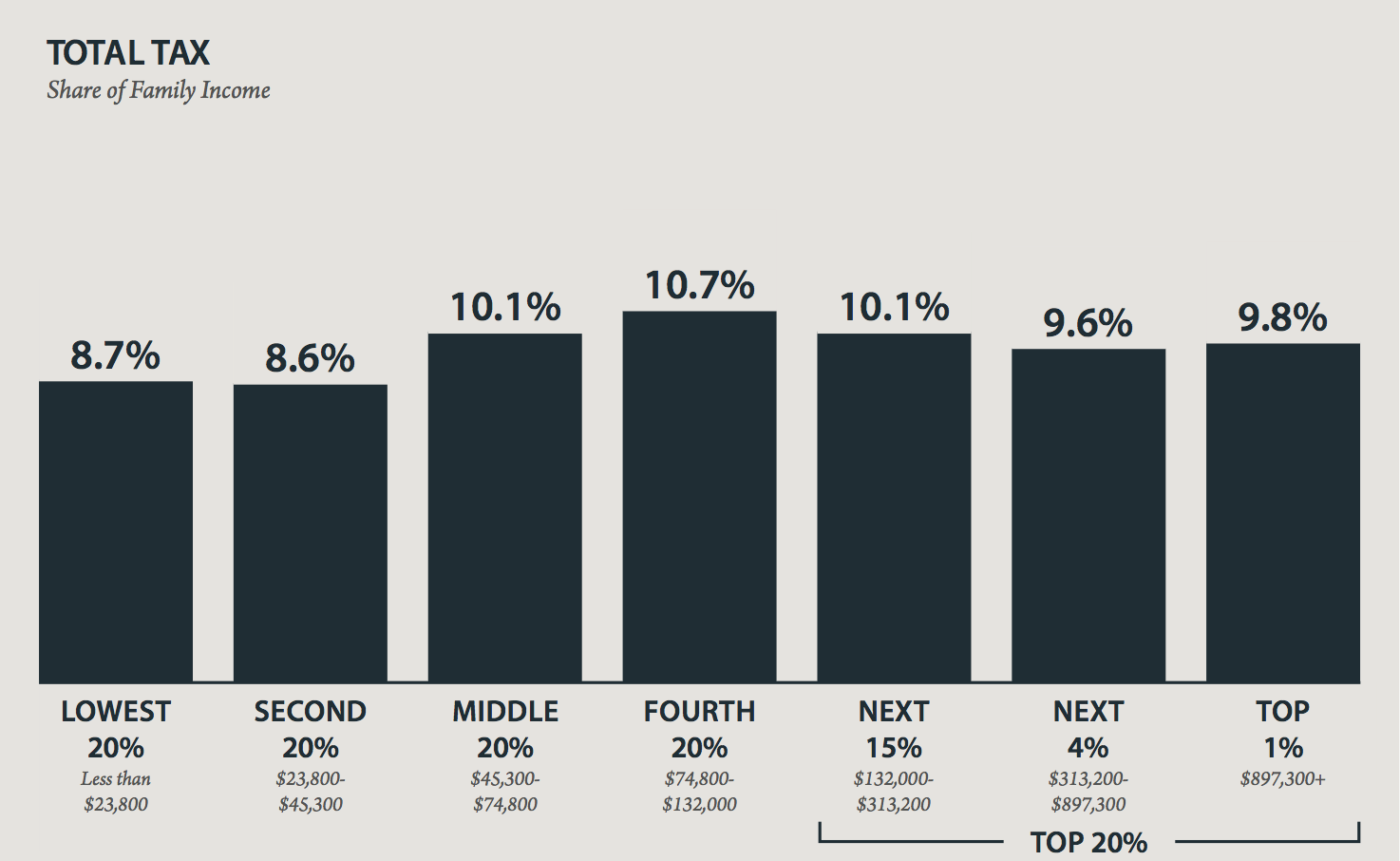

And while there are many factors that contribute to rising inequality, New Jersey’s tax code isn’t helping. Under the current tax code, New Jersey’s middle-class families pay a greater share of their income in state and local taxes than the top 5 percent of households do. This is unfair, exacerbates income inequality, and makes it harder for middle class families to thrive. Increasing taxes on top earners will make New Jersey’s tax code more progressive and help ensure future state budgets are no longer balanced on the backs of middle class families. And because New Jersey’s income tax is dedicated to the Property Tax Relief Fund, this revenue will help to reduce property taxes throughout the state while also freeing up other revenues to invest in state assets.

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? 6th Edition

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? 6th Edition

Dispelling Myths and Respecting Public Support

The need for a millionaires tax is clear. Inequality is dangerously high and continues to grow. The state’s tax code is still not as progressive as it could and should be. But, despite mounting evidence that this proposal is necessary and fair, opponents of a millionaires tax contend that such a move would cause the state’s wealthiest residents to flee for lower-tax pastures, an argument known as “millionaire tax flight.” It’s a common misconception built on decades of misinformation and anecdotal evidence. Luckily, there’s plenty of research and data to show that “millionaire tax flight” is a total myth.

New Jersey Policy Perspective has repeatedly busted the myth of “millionaire tax flight,” and our research echoes similar findings of researchers at independent, national policy organizations and peer reviewed research institutions. The tax flight myth has been busted by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Tax Policy Center, and Stanford University. And if you’re looking for a longer read on the subject, Cornell University professor Cristobal Young wrote the book on it. And yet, despite NJPP repeatedly publishing and sharing comprehensive analyses showing that high tax rates do not cause the wealthy to move, elected officials have continued to buy into the lie and use it as an excuse to protect the wealthy from fair and proper taxation.

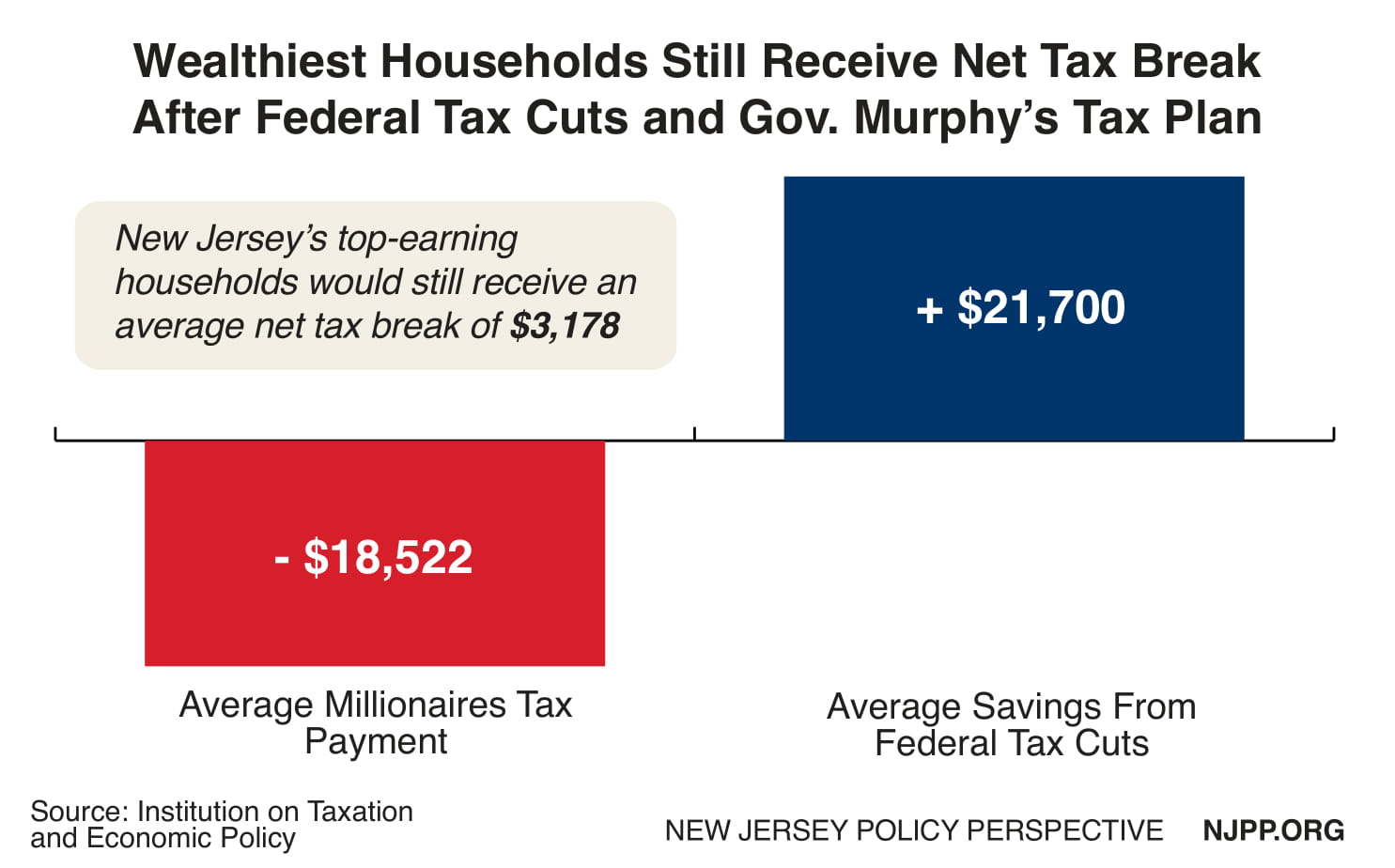

After the 2017 federal tax changes, some legislators expressed concern that implementing a millionaires tax now would be a mistake, claiming that wealthy households in New Jersey couldn’t afford an increase in their income taxes because the federal changes negatively affected them. These fears are unfounded. When accounting for the federal tax changes along with a state millionaires tax, New Jersey’s top one percent of tax filers still receive a net tax cut of approximately $3,200.

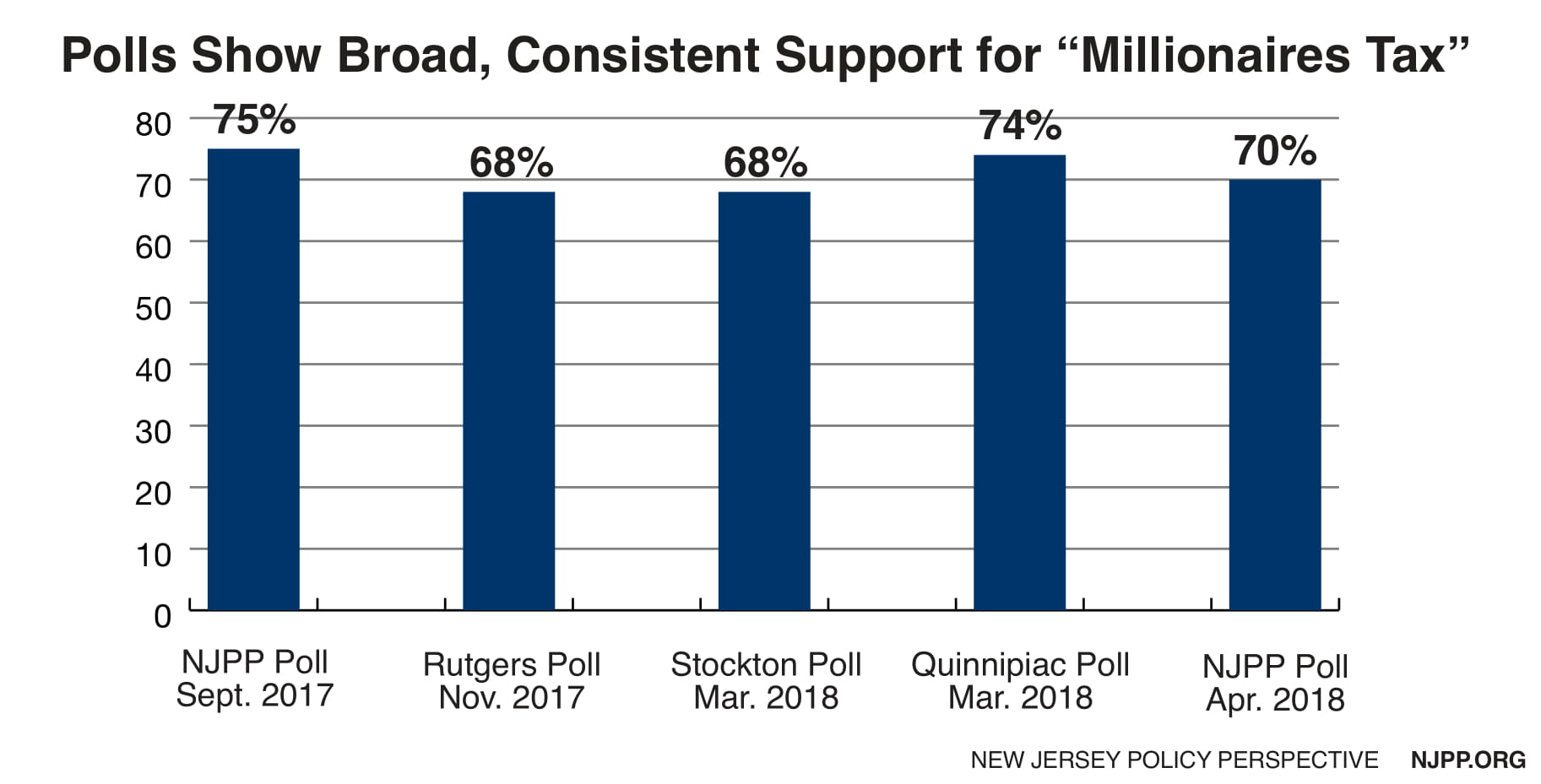

And when legislators aren’t knocking the merits of a millionaires tax, they often claim it’s unpopular and their constituents don’t support it. This perspective is particularly hard to believe considering the recent federal election where progressive and liberal candidates, running on platforms that included fair taxation and policies to tackle income inequality, came within one seat of sweeping the state’s congressional races. But this isn’t a matter of opinion — there are mounting statewide polls that show Governor Murphy’s millionaires tax is incredibly popular.

When Governor Murphy first proposed a millionaires tax during last year’s budget negotiations, polls conducted by Rutgers University, Stockton University, Quinnipiac University, and a poll commissioned by NJPP, all came to the same conclusion: a millionaires tax has broad, bipartisan support across the state. The polls found that up to 75 percent — and no less than 68 percent — of voters support a millionaires tax. These polls should provide relief to legislators who fear the political consequences of taking on growing inequality. If anything, failing to support the millionaires tax would be more dangerous with three in four New Jerseyans supporting it. Combine this with the reality of growing inequality and bold proposals from 2020 presidential candidates to fairly tax the nation’s wealthiest residents and it’s clear that tax policy is becoming a more important issue in future elections.

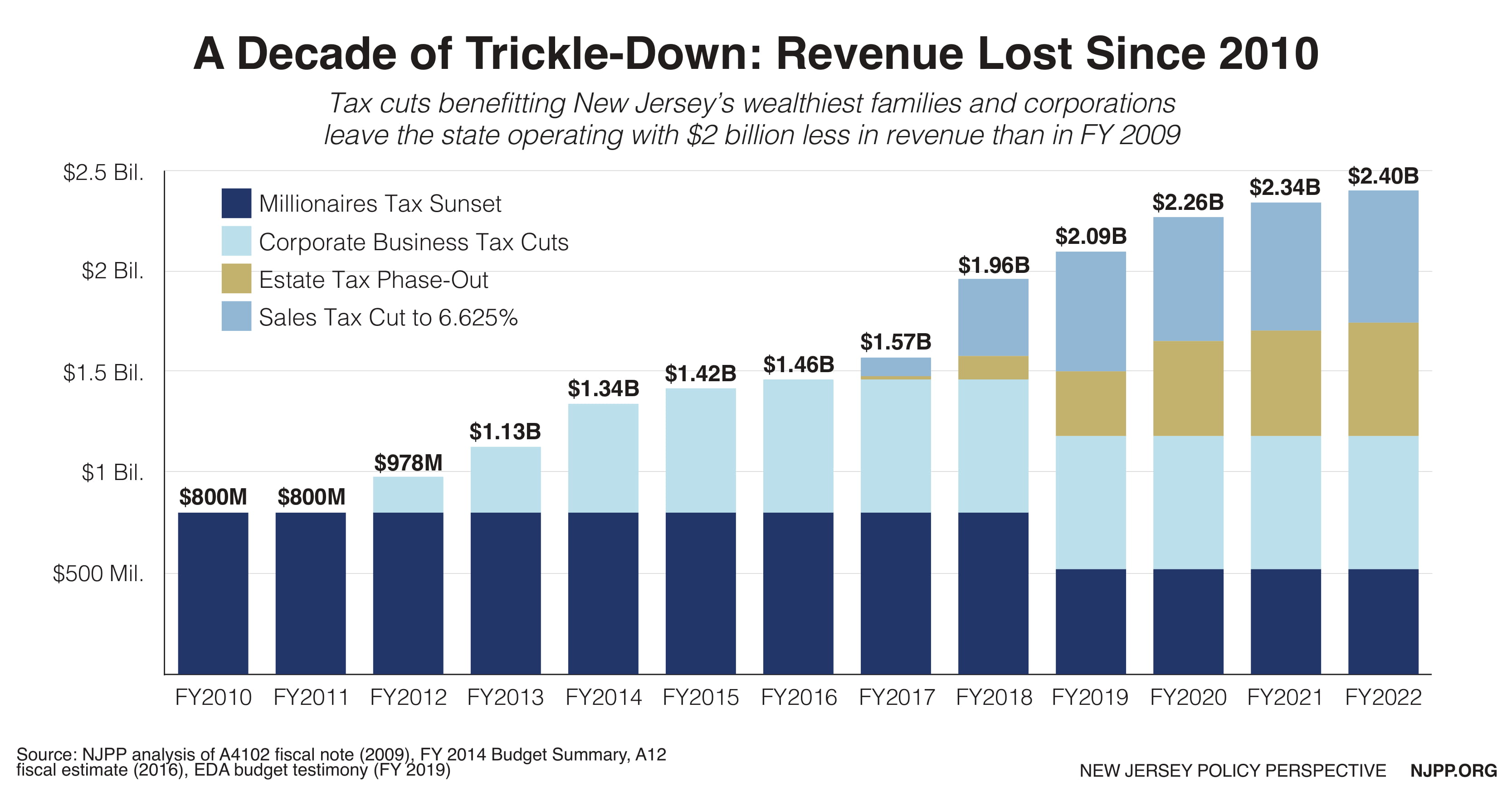

The Legislature Must Finish the Job it Started in 2010 and Pass the Millionaires Tax

While many legislators are expressing opposition to implementing a millionaires tax — despite all of the evidence that it is extremely popular with voters and doesn’t cause the wealthy to flee — you don’t have to go too far back in history to a time when they were fully supportive of the idea. Under Governor Christie, the full legislature passed a millionaires tax five times (in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, and 2015). Of course, the governor vetoed their efforts every time, but legislators took a bold stance, on the record, in support of tax fairness with each vote. In fact, in 2014, legislative leadership proposed putting the millionaires tax on the ballot as a constitutional amendment to help increase state revenues for critical investments and make the tax code more fair. All of this created anticipation and expectation that if a governor who supported the policy took office after Governor Christie, the legislature would gladly work with them to implement something that they tried and failed to do five times previously. Now with Governor Murphy including the proposal in his budget, the legislature would be wise to join him in completing the task.

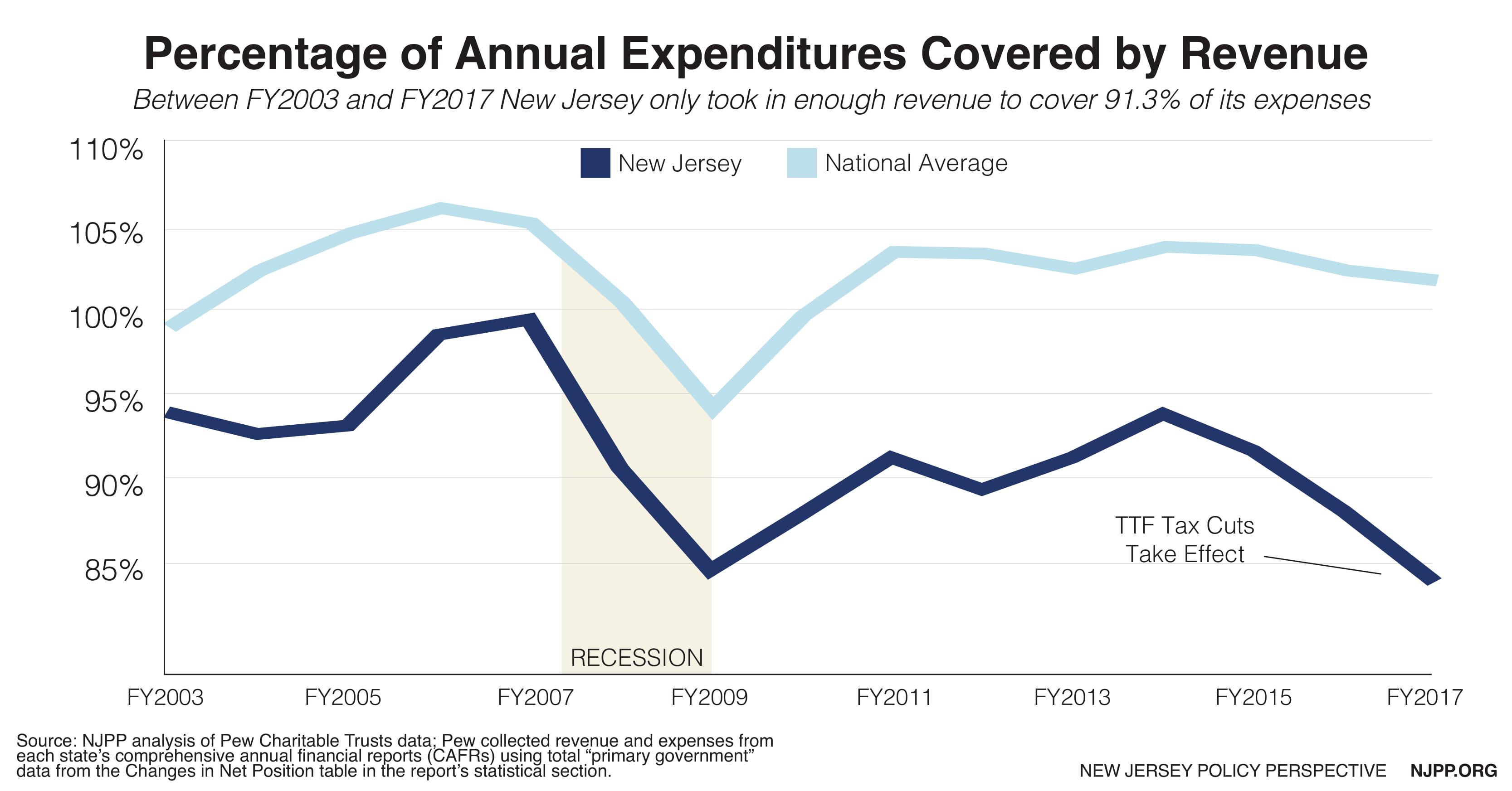

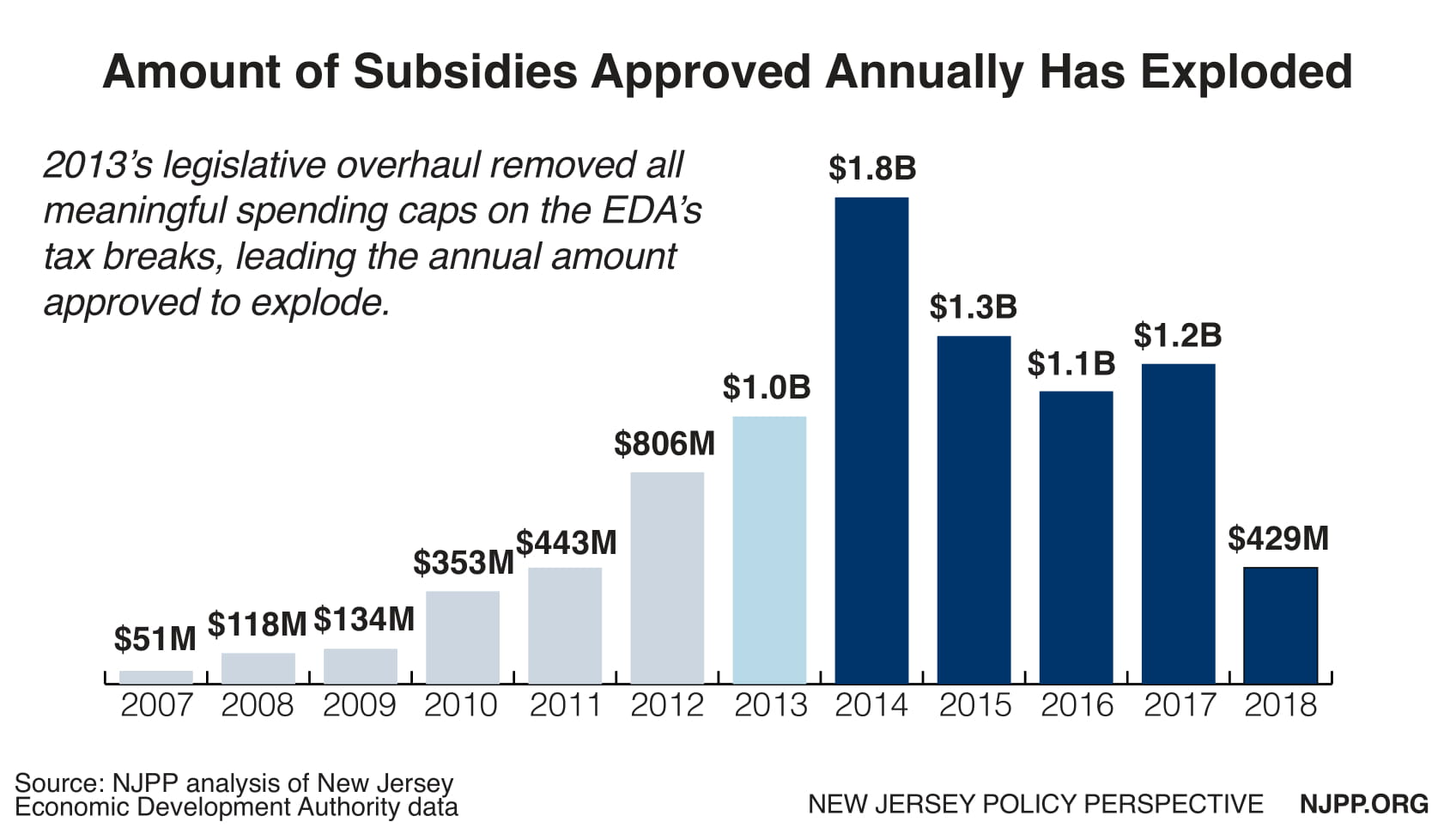

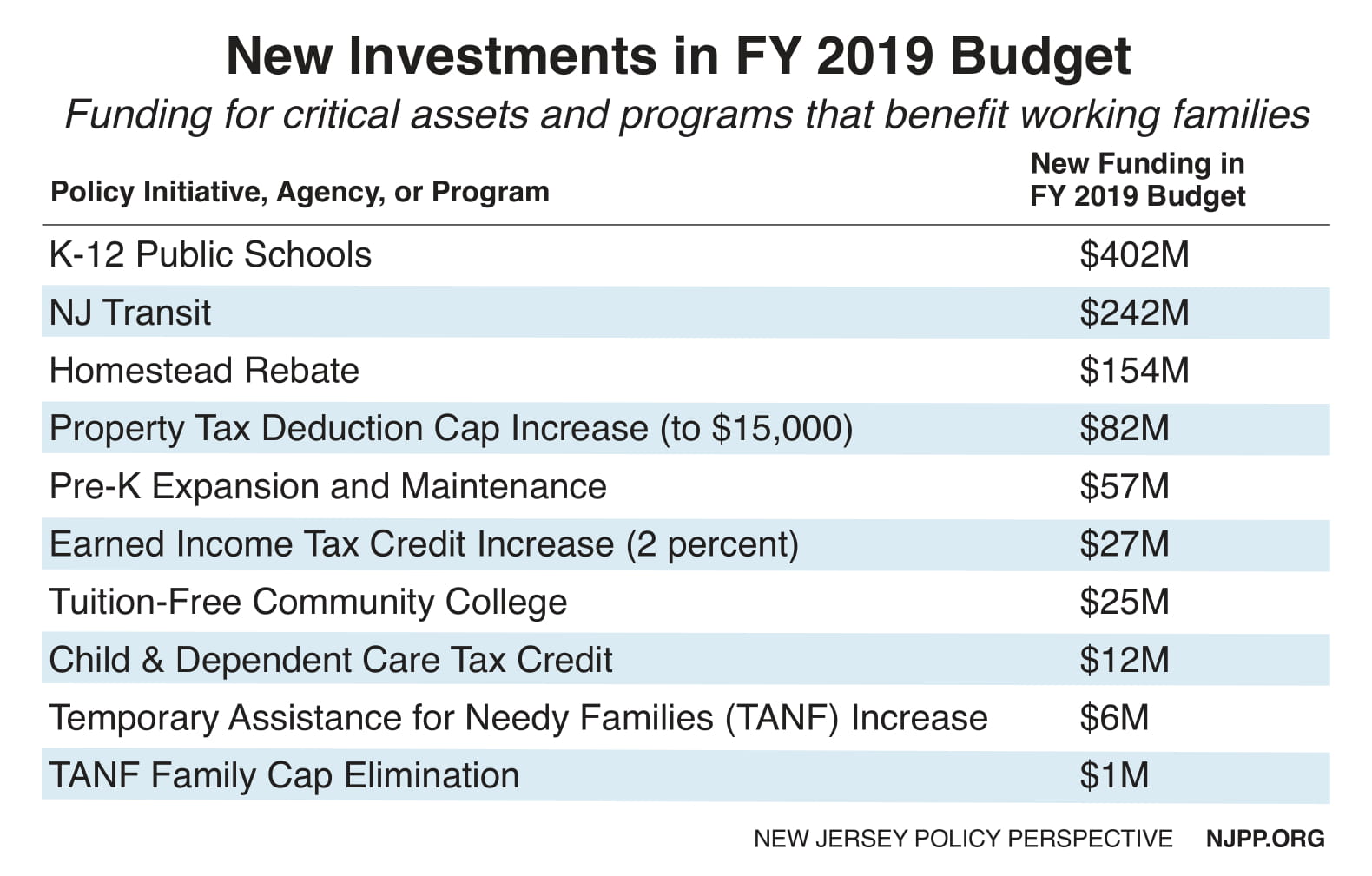

Since those failed efforts by the legislature under the previous administration, income inequality has only gotten worse and state assets are still in desperate need of increased and reliable sources of funding. Many state departments continue to struggle with funding levels no higher than they were under Governor Christie, our institutions of higher education still have less general operating support than they did prior to the Great Recession, and New Jersey Transit — while better than it has been in recent years — remains in need of more funding so it can modernize its system and meet the daily needs of New Jersey commuters.

To summarize: there is no such thing as millionaire tax flight and the 2017 federal tax changes were a massive boon to wealthy earners, so concerns about the welfare of the rich have no basis in reality; voters have always shown high levels of support for a millionaires tax, so any worries by lawmakers that passing the policy on to the governor’s desk would have political consequences are completely unfounded; and the state’s assets still require significant investments after eight years of cuts.

The bottom line is a millionaires tax is a critical budgetary tool that will help New Jersey meet its needs. Lawmakers should have passed it last year when the governor proposed it in his first budget and they have even more reason to do so now. It’s far past time to take this important step and bolster our budget, make our tax code fairer, and respect the wishes of the state’s voters. Pass the millionaires tax now and make New Jersey a fairer and better place to live.