To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

A drastic change in the “public charge” rule proposed by the Trump administration would restrict access to green cards and various types of visas for immigrants who are not already comparatively well-off. This “Trump Rule” fundamentally changes our approach to immigration, making family income and potential use of health care, nutrition or housing programs a central consideration in whether or not to offer people an opportunity to make their lives in this country. The Trump Rule takes an existing standard and proposes to make it vastly more restrictive.

The Chilling Effect

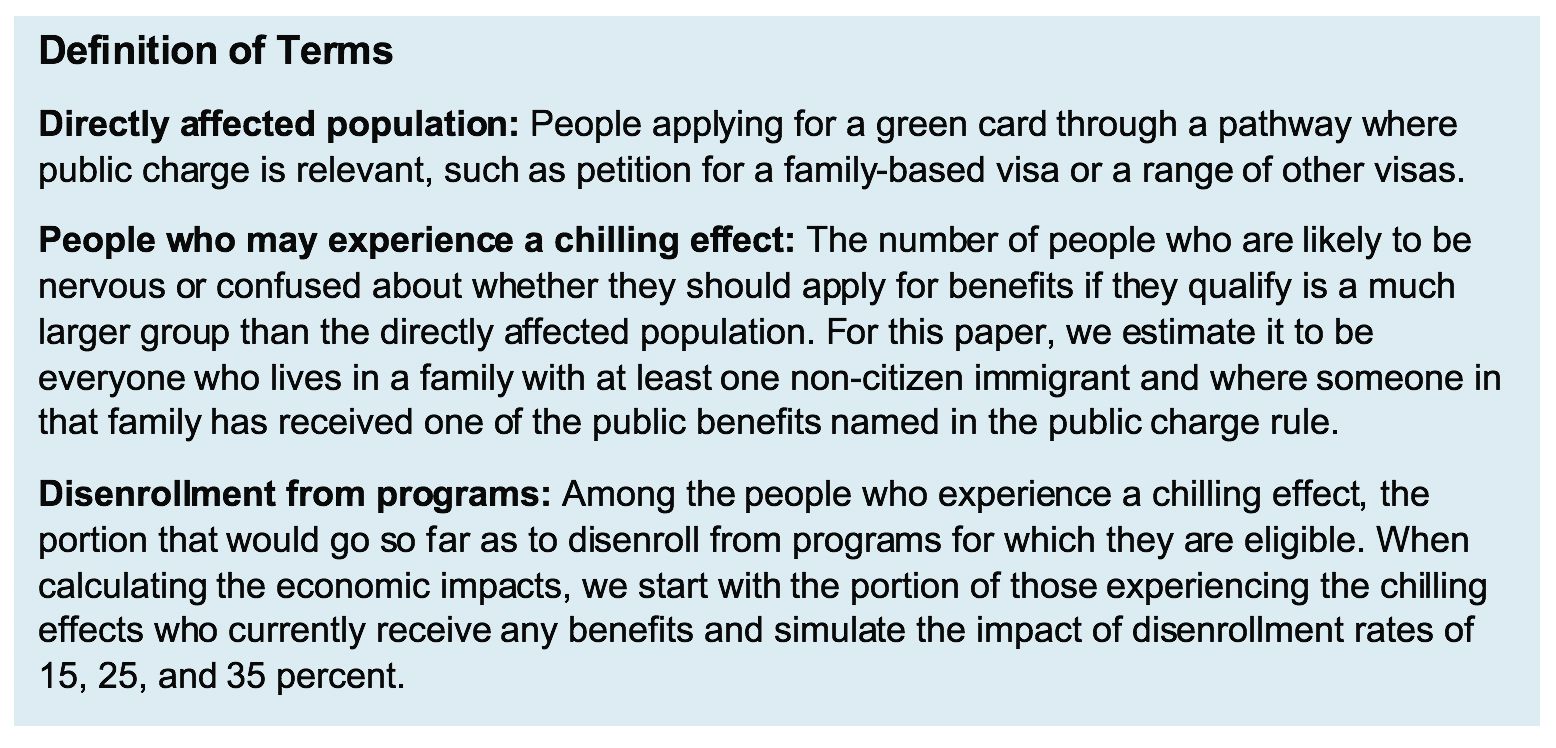

The direct effect of the Trump Rule would fall primarily on people applying for a green card through a family-based petition,where public charge is relevant. Similar standards would also apply to people seeking to extend or change their temporary non-immigrant status in the United States. The rule change would likely lead to the denial of green cards to hundreds of thousands of otherwise eligible applicants for family-based and employment visas.

The direct effect of the Trump Rule would fall primarily on people applying for a green card through a family-based petition,where public charge is relevant. Similar standards would also apply to people seeking to extend or change their temporary non-immigrant status in the United States. The rule change would likely lead to the denial of green cards to hundreds of thousands of otherwise eligible applicants for family-based and employment visas.

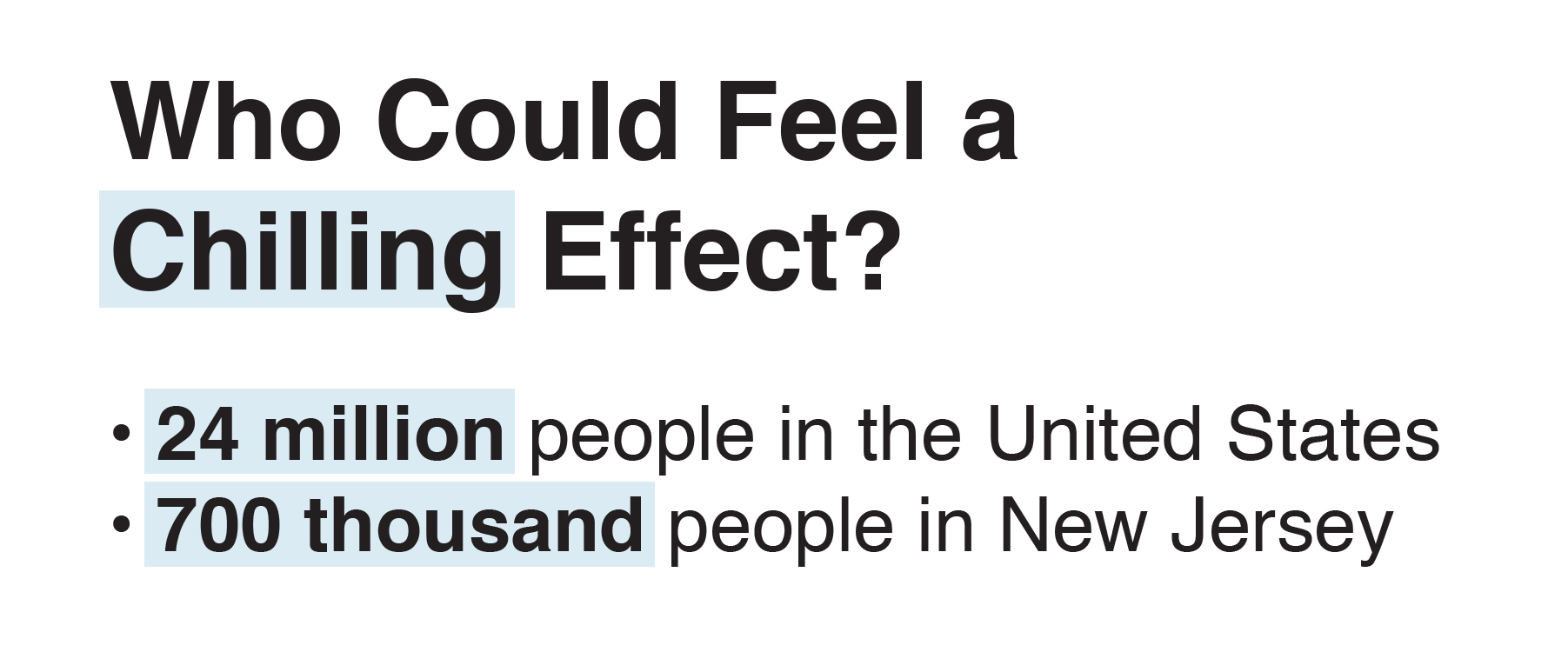

Beyond that, if implemented the Trump Rule is also expected—and perhaps intended—to have a widespread chilling effect. Even people who already have a green card, or who are exempt from the rule, such as refugees or asylees, are expected to be frightened and confused about the potential consequences of applying for food, health, and housing supports they are eligible to receive.

We estimate that 24 million people in the United States would be affected by the chilling effect of the Trump Rule, including 700,000 New Jerseyans. Not all will face a public charge determination, but all are likely to be nervous about applying for benefits, and some portion will in fact disenroll from benefit programs.

Our estimate of the population who may experience a chilling effect includes anyone in a family that has received any food, health, or housing supports, and where at least one member of the family is a non-citizen. Based on past experience, there is good reason to believe that when there are changes around immigration and public benefits even people who are not directly targeted by this rule will be affected. Indeed, there is already evidence that significant numbers of immigrants are withdrawing from Women, Infants, Children, known as WIC, despite the fact that the program is not included in the Trump Rule and the rule has not yet been implemented.[1]

The Trump Rule Goes Too Far

The Trump Rule uses the public charge designation as a way to unilaterally change immigration policy, without input from Congress, fundamentally redefining how we think about who an “acceptable” immigrant is and undercutting the very idea of the American Dream.

The pre-existing public charge rule has required immigration officers to evaluate the overall circumstances of immigrants to determine whether they can support themselves in the United States or whether they are likely to rely primarily on the government for support. Under longstanding policy, this has meant showing an applicant will not become primarily dependent on the government—relying, for example, on cash aid from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental Security Income, or General Assistance for their monthly income, or on long-term institutional care.

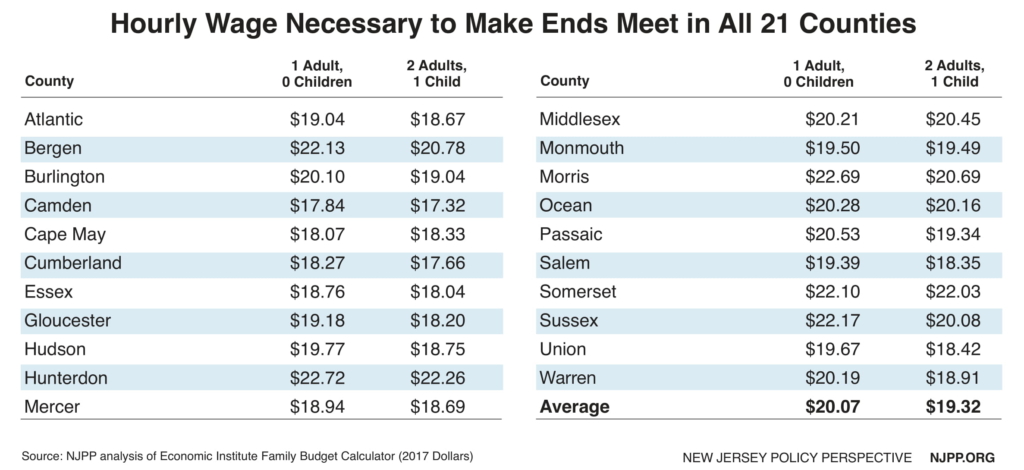

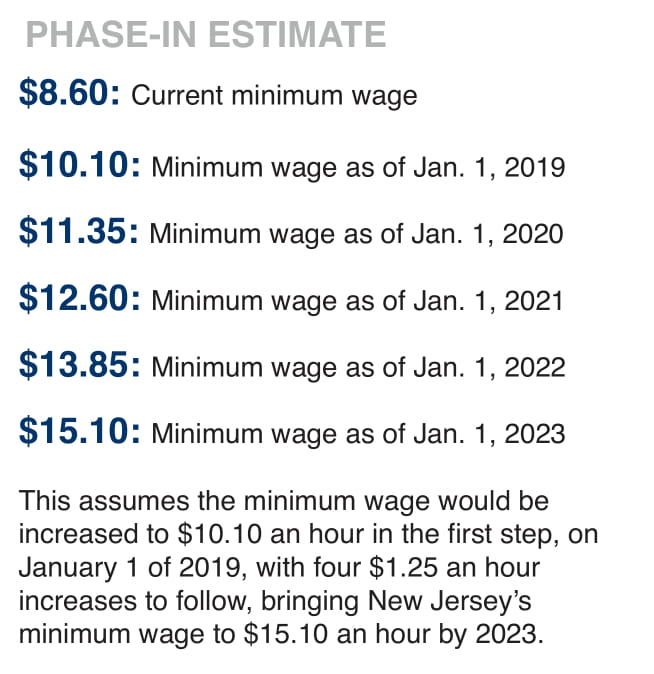

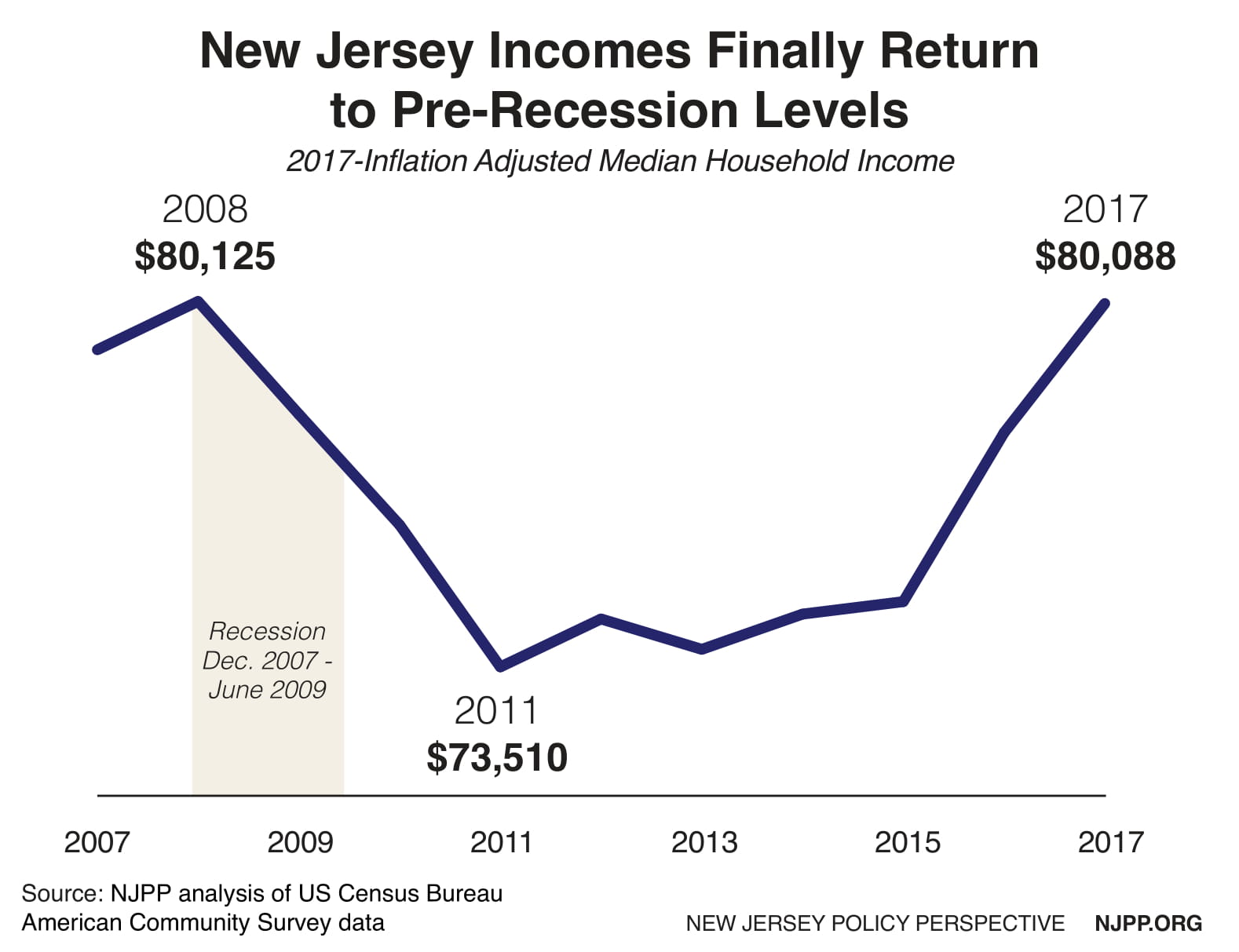

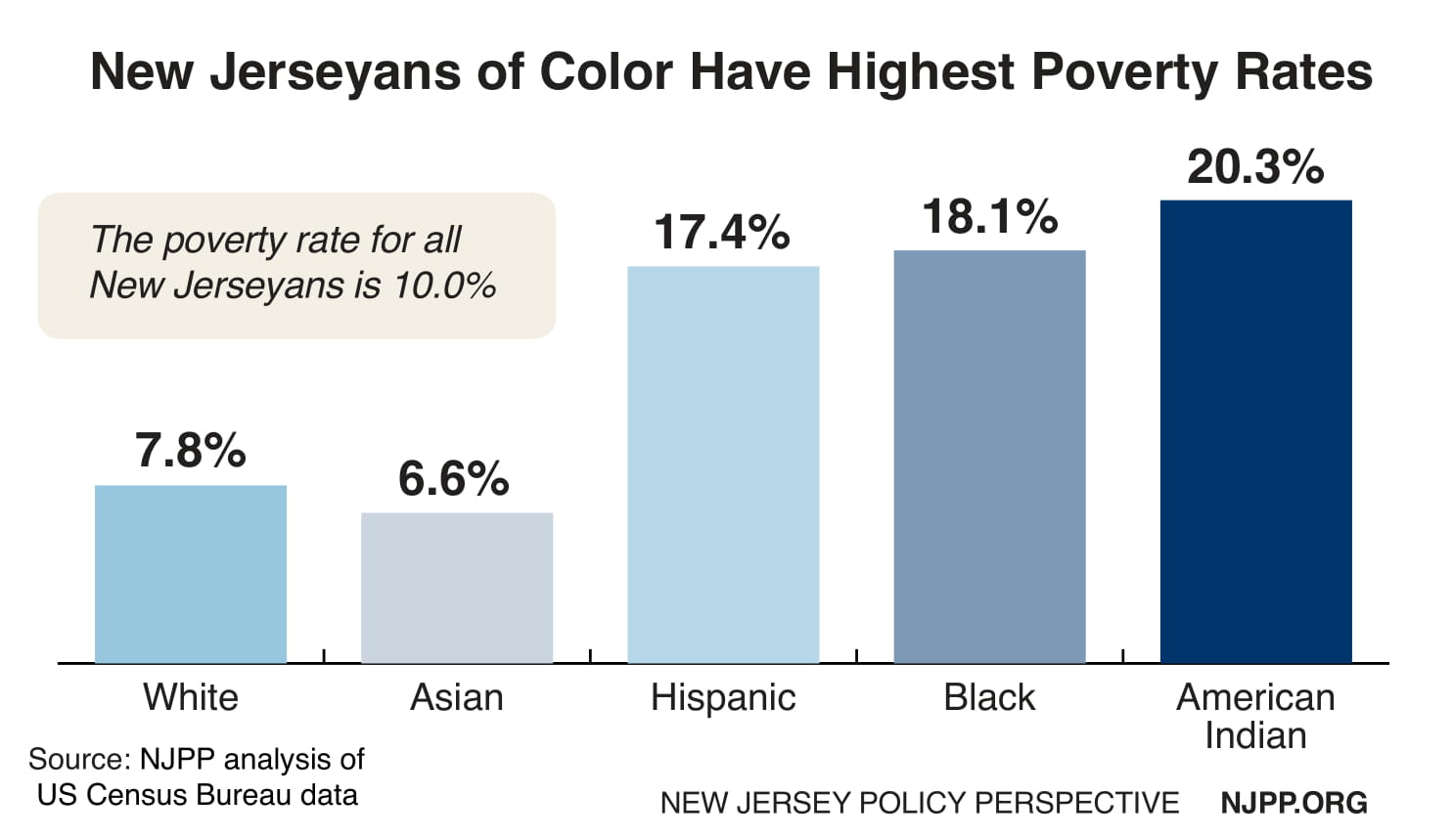

The Trump Rule aggressively reinterprets this longstanding policy. While continuing to look at the overall circumstances of a family, the Trump Rule would deem immigrants potentially unacceptable if they have received, or are considered likely to receive, even a modest amount of support from any one of a number of non-cashsupports: Medicaid, food stamps (SNAP), housing supports, and subsidies for Medicare Part D to reduce the cost of prescription drugs. It would also—for the first time—make a specific income threshold a central issue in immigration decisions. Having an income of under $15,000 for a single person or $31,000 for a family of four would be weighed negatively and could lead to a denial. Indeed, the rule proposes to weigh a range of factors negatively. The only factor weighed as “heavily positive” is if an applicant has an income or resources of over $30,000 for a single person or $63,000 for a family of four. By way of comparison, the median household income in the United States is $60,000.[2]

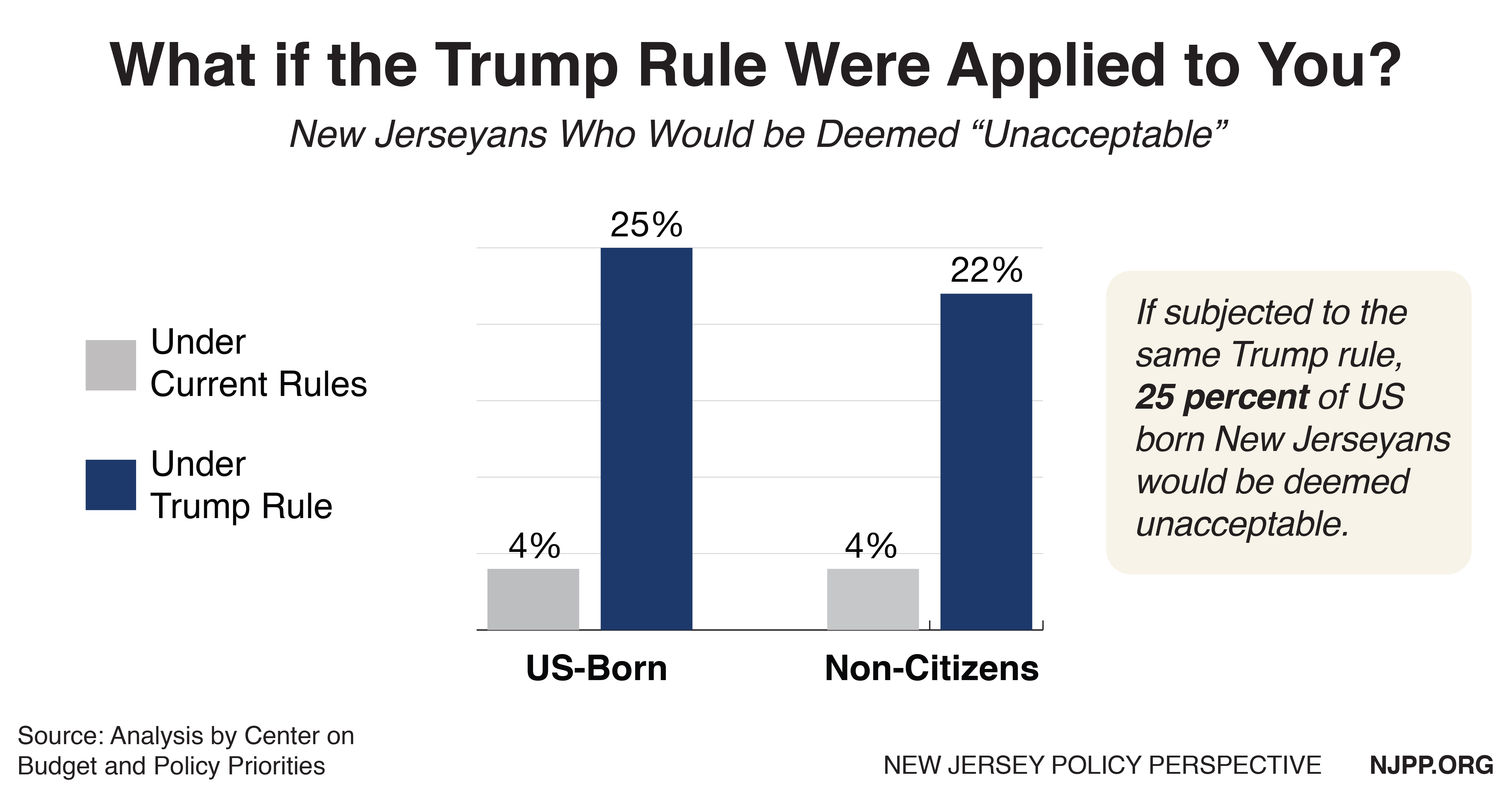

As noted, only some non-citizens currently in the United States will face this Trump Rule; many will not. But what would it look like if we applied the Trump Rule to all non-citizens?

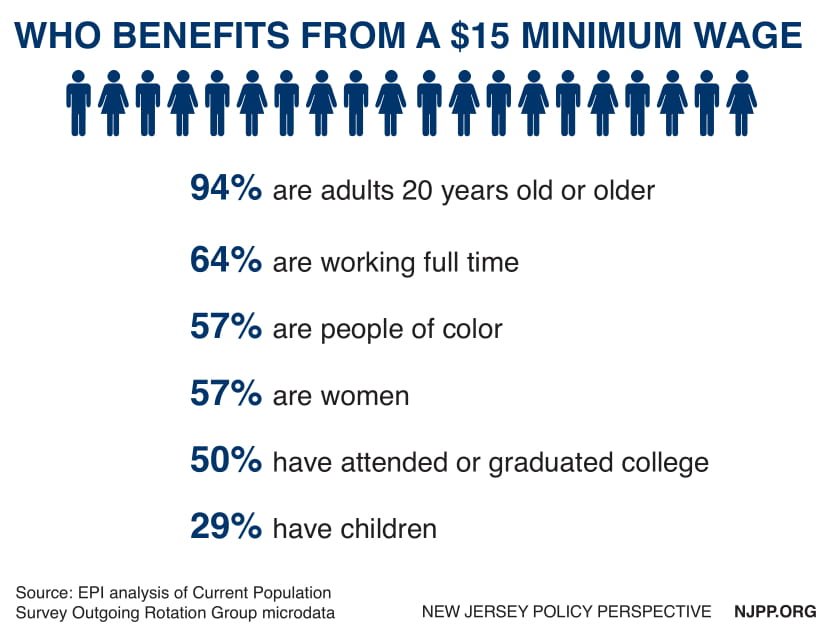

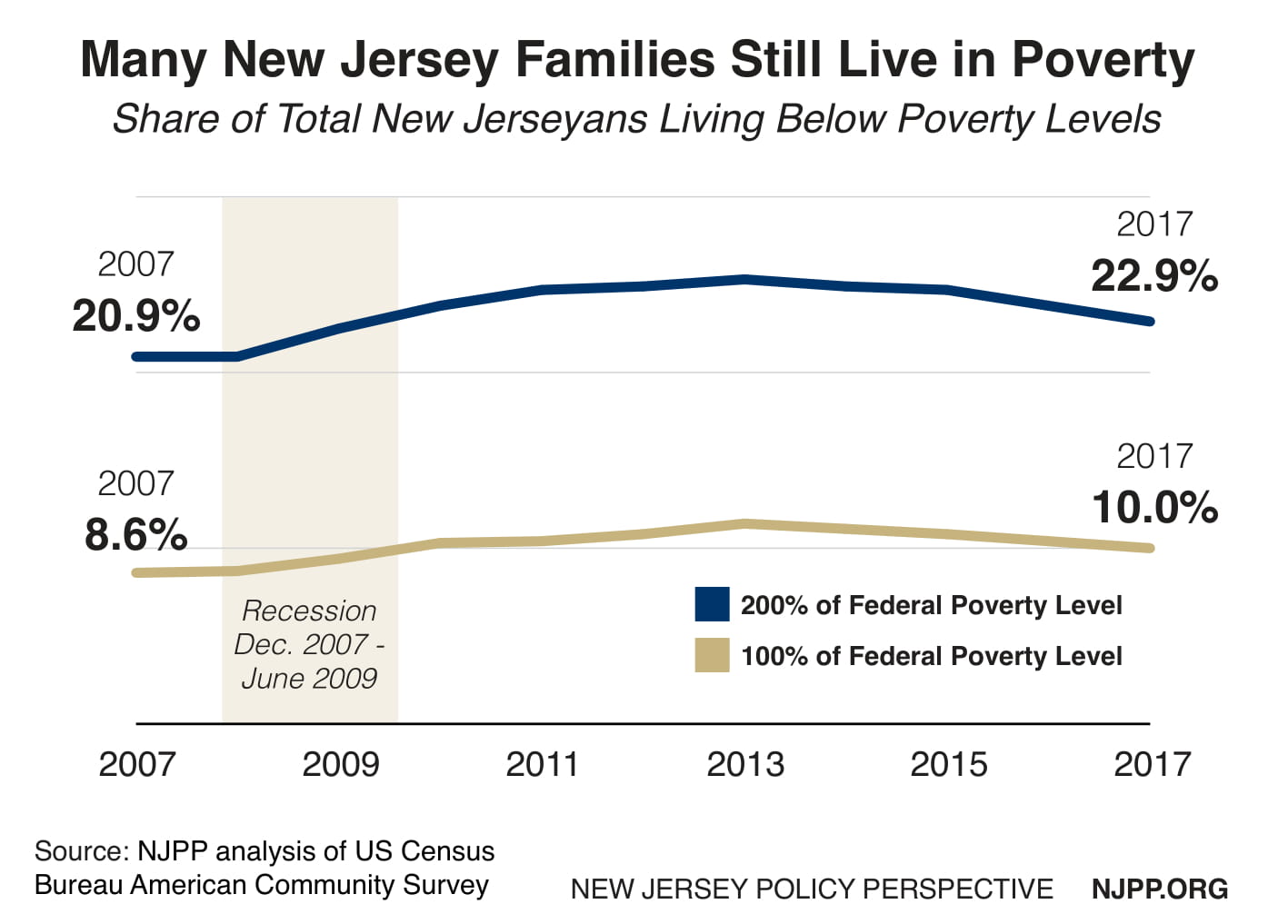

The effect is extreme: in New Jersey State, 22 percent of non-citizens have benefited from health care, food, housing, or cash supports. That should come as no surprise: so have 25 percent of US-born New Jerseyans. The fact is, a large number of Americans—whether or not they are immigrants—make use of federal food, health, and housing programs in any given year to get through hard times and to advance to a better life.

Most of these programs are structured in significant measure as work supports, helping people with relatively low-wage jobs keep healthy, stay in their homes, and put food on the table. Discouraging families from making use of these programs only makes it harder for them to move up the economic ladder and fully contribute to the economy.

Further Inhumane Treatment of Kids to Pressure Families

The nation was outraged to find out that the Trump Administration has been using the forced separation of children from their parents as an inhumane tactic of immigration enforcement.[3] The redefinition of public charge doubles down on this strategy by inflicting harm on children, whether intentionally or as a side effect of the Trump Rule.

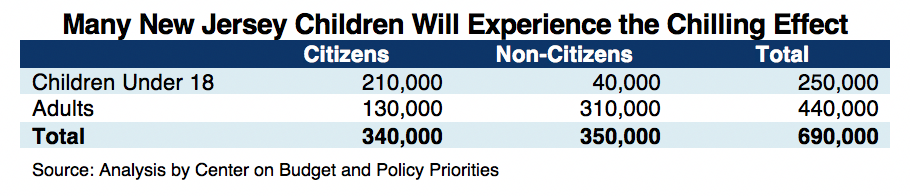

Some children will themselves be subject to the Trump Rule.[4] A far greater number live in families that will likely experience a chilling effect. In New Jersey, 250,000 children under 18 years old live in families with at least one non-citizen family member and that have received one of the benefits specified by the Trump Rule. The large majority or 84 percent, 210,000 of the 250,000 are United States citizens.

It also pushes parents to make heart-wrenching decisions for their families. The stakes are unbearably high. As a parent, if you apply for SNAP or Medicaid, you may fear losing the chance to stay in this country with your kids. Yet, not applying may mean seeing your family go hungry or not being able to see a doctor when you are sick.

If the Trump Rule is put into effect, advocates and service providers will need to work strenuously to clarify which individuals may be directly impacted and which may be relatively safe. But confusion and fear will undoubtedly spread well beyond the directly targeted population.

Helping children in immigrant families do well is not only the right thing to do, it’s also a sound investment in our state and the nation’s future. One of the clearest and most striking findings in a major study of the National Academy of Sciences is that the children of immigrants, once grown, become among the strongest contributors to the country’s economy.[5]

An Economic Loss for New Jersey

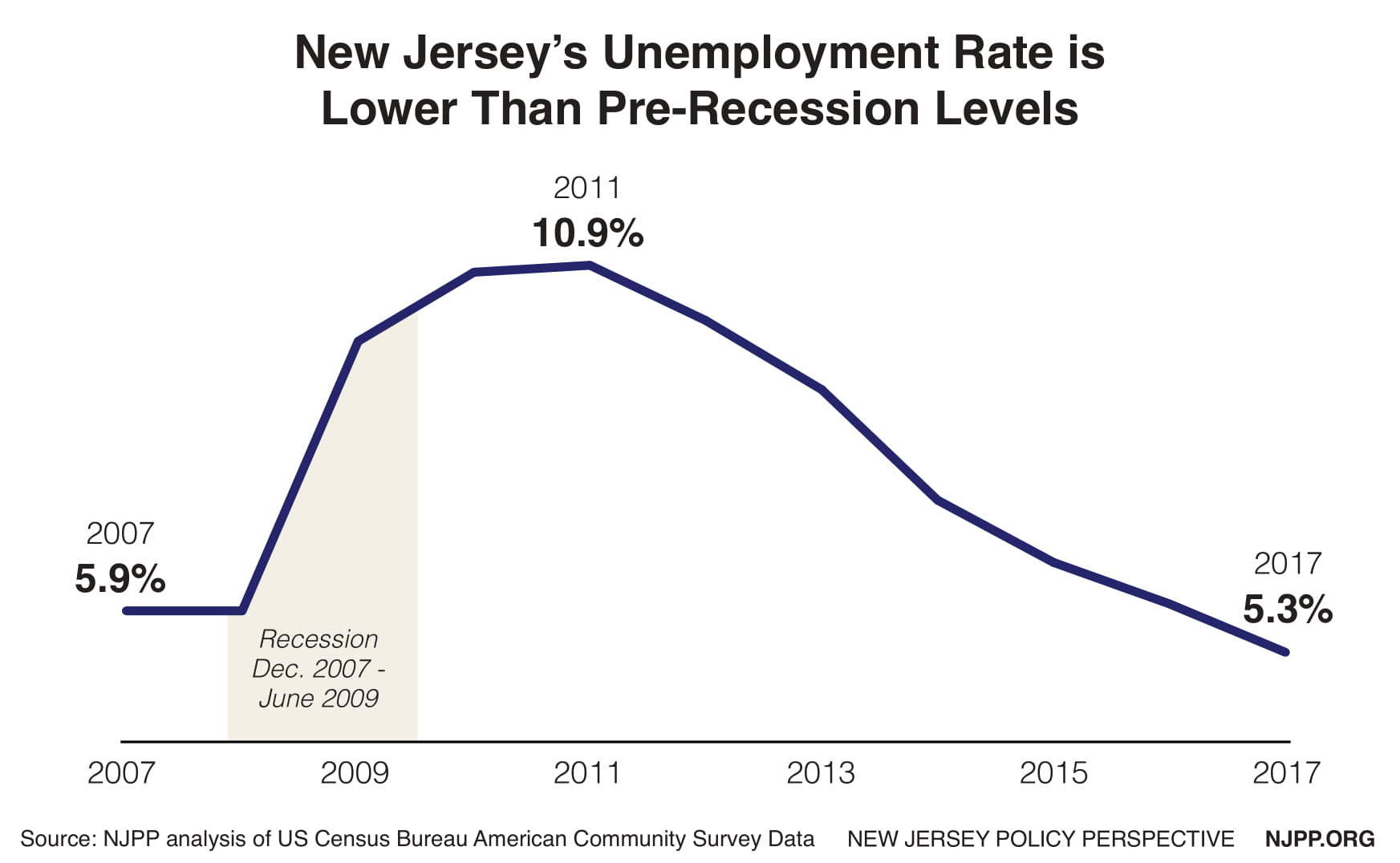

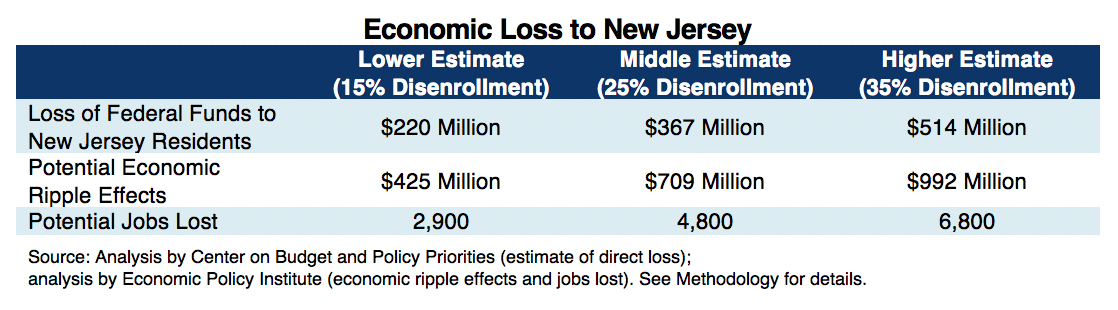

To measure the economic impact on New Jersey, we modeled the impact of two of the biggest supports the Trump Rule would affect: SNAP and Medicaid. We provide estimates of the impacts if 15, 25, and 35 percent of people currently receiving benefits who experience the chilling effect feel compelled to disenroll from programs for which they qualify. This range of disenrollment is derived from studies of comparable policy changes that similarly created a chilling effect for immigrants, such as welfare reform in the 1990s.[6] The middle-level estimate shows a loss of $425 million in direct federal dollars coming into the state.

If money on this scale is withdrawn from the New Jersey economy, there would be predictable ripple effects to local businesses and workers. Withdrawal of SNAP funding means a reduction in spending in grocery stores and supermarkets. When families lose health insurance, hospitals and doctors lose income.[7] And some spending would be reduced in other areas as families struggle to pay food and health costs. Our mid-level estimate shows a potential loss of $709 million due to the ripple effects of this lost spending.[8]

Further, when businesses have less revenue, they lay off workers. Translating the job loss implied by an economic loss of this magnitude, based on the number of jobs implied per dollar of gross domestic product, New Jersey stands potentially to lose as many as 4,800 jobs under our middle estimate as a result of this reduction in federal funding coming to the state.[9] The economic impact would vary depending on where the country is in the business cycle. Because these programs serve as an important economic stabilizer, they create a bigger stimulus during an economic downturn and less in a period of high growth.

At the lower level, with just 15 percent of people receiving benefits disenrolling, the modeled loss of federal dollars to New Jersey State is $ 220 million, the potential economic ripple effects are $425 million, and the potential job loss is 2,900. At the higher estimate, with 35 percent disenrollment, the loss of federal funds in New Jersey is $514 million, the potential ripple effects are $992 million, and there could be as many as 6,800 jobs lost.

Conclusion

From the beginning, the United States has been a place where immigrants have come to make a new life. In this country, many immigrants and US-born workers alike have climbed from the lowest rungs of the economic ladder into the middle class and beyond. It was the opportunities America provided—and often enough the supports they needed to get started or make it through hard times—that allowed them to succeed. This is the story of the American Dream. And it is the story engraved in poetry on the Statue of Liberty.

The Trump Rule sees America’s story differently, as one governed by barriers and fear of newcomers. By suggesting that only immigrants who are already above a certain income threshold are welcome, the Trump Rule shows a disturbing lack of faith in our country and the opportunities it provides.

Methodology

- Estimating the Population That Would Experience a Chilling Effect

We define the population that would experience a chilling effect as those who might be nervous and confused by the new rule and might feel like they need to make a choice between applying for needed benefits and avoiding putting their family at risk. As noted in the body of this paper most of the people experiencing a chilling effect are people who will not have to go through a public charge determination.

In order to estimate the size of the population experiencing a chilling effect, the Fiscal Policy Institute uses estimates provided by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) of the number of people living in families where at least one person is a non-citizen, and where someone in that family has received one of the public benefits named in the proposed public charge rule. The analysis uses the Current Population Survey and corrects for underreporting of SNAP, TANF and SSI receipt in the Census survey using data from the Department of Health and Human Services/Urban Institute Transfer Income Model (TRIM). These TRIM corrections take into account program eligibility rules by immigration status. Three years of data are combined in order to increase sample size and improve the reliability of the state-level estimates: 2013 to 2015, the most recent for which the TRIM-adjusted data are available. National level estimates are based on data just from 2015.

CBPP’s calculations of program participation include the newly considered programs —Medicaid, SNAP, and housing benefits—as well as those already considered—TANF, SSI, and General Assistance. The Census data for Medicaid used by CBPP also include the closely intertwined Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Most participants can be expected to have a very hard time distinguishing between a program funded by Medicaid and one funded by CHIP. The proposed rule does not presently include CHIP, but the notice announcing the proposal explains that the administration is considering including it. Medicare Part D low-income subsidies are included in the proposed rule but were not included in CBPP’s estimates due to a lack of a Census variable that identifies those participants. To model the current public charge benefit related test, CBPP looked at those people who get more than half of their income from TANF, SSI, and General Assistance.

- Estimating the Economic Loss to New Jersey

Among the people who experience a chilling effect, some portion would go so far as to disenroll from programs for which they are eligible.

The estimate of the direct loss to New Jerseyans from disenrollment from these programs begins with SNAP, Medicaid and CHIP federal funding data. The estimates use administrative and survey data to approximate the amount of benefits received by families that include a non-citizen. This is the population that due to fear or confusion could forgo benefits even though most of them are themselves not likely to be subject to a public-charge determination. In estimating the economic consequences of the Trump Rule, we assume that only a portion of this group will actually disenroll from these food, health, housing, or cash supports. While a lot is at stake for people in families with a non-citizen immigrant if they fear running afoul of the public charge rule, there is also a lot at stake in not applying and having your family go hungry or lack health insurance. Again, we include CHIP in our estimates.

In our estimates, we assume a range of 15 to 35 percent of the people experiencing a chilling effect will disenroll from SNAP and Medicaid. We provide estimates of the economic effects of the higher and lower disenrollment rates as well as the midpoint of 25 percent. In doing this, we follow the Kaiser Family Fund’s paper of February, 2018, “Proposed Changes to ‘Public Charge’ Policies for Immigrants: Implications for Health Coverage,” which provides a review of the literature leading to this estimate range.[10] We do not attempt to simulate the consequences of adverse selection—for instance, that healthier people may be more likely to withdraw from health care coverage than less healthy people. The 15, 25, and 35 percent disenrollment rates are already a broad range and not a precise prediction.

To estimate the economic ripple effects, the Fiscal Policy Institute uses an analysis provided to us by Josh Biven of the Economic Policy Institute. The analysis takes the direct benefit loss as calculated above and applies to it an output multiplier for SNAP of 1.6, in line with estimates Bivens summarizes in a 2011 paper.[11] The Medicaid multiplier is 2.0 and is drawn from an analysis of the effects of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.[12]

After calculating the effect of benefit reductions on output, the output was divided by $146,880 to obtain an estimate of the effect on employment, on a full-time equivalent (FTE) basis. This employment multiplier was obtained by dividing U.S. gross domestic product in 2017 by the number of FTEs in that year.[13]

The economic impact can be expected to vary with the state of the economy. The economic and job loss of the Trump Rule will be greater in times of high unemployment, and lower in times of full employment. Since the Trump Rule is proposed to be permanent, the effect could be expected to vary.

Endnotes

[1] See Helena Bottemiller Evich, “Immigrants, Fearing Trump Crackdown, Drop Out of Nutrition Programs,” Politico, September 3, 2018.

[2] The rule gives a family income of below 125 percent of the federal poverty level as a negatively weighing factor, and above 250 percent of the poverty level as a positively weighing factor. We translate those into dollar figures for different family sizes using the 2018 poverty level. Household income is a Fiscal Policy Institute analysis of the 2017 American Community Survey 1-year data. Household income includes individuals of varying size including households of just one person.

[3] As Attorney General Jeff Sessions put it: “we will prosecute you, and that child will be separated from you as required by law. If you don’t like that, then don’t smuggle children over our border.”[iii]See Rafael Carranza and Daniel González, “AG Sessions Vows to Separate Kids from Parents, Prosecute All Illegal Border-Crossers,” The Republic, May 8, 2018.

[4] Disturbingly, for those children who do apply for status that requires a public charge designation, the Trump Rule penalizes children by weighing their age negatively. The theory, presumably, is that children do not adequately contribute to the economy.

[5] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2017. For a brief synopsis of major findings, see the press release at http://www8.nationalacademies.org/onpinews/newsitem.aspx?RecordID=23550.

[6] Our estimate of disenrollment follows the analysis of “Proposed Changes to ‘Public Charge’ Policies for Immigrants: Implications for Health Coverage,” Kaiser Family Foundation, September 24, 2018. That report cites: Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), (June 2005), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361164/; Michael Fix and Jeffrey Passel, Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform 1994-97 (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, March 1, 1999) https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/69781/408086-Trends-in-Noncitizens-and-Citizens-Use-of-Public-Benefits-Following-Welfare-Reform.pdf; Namratha R. Kandula, et. al, “The Unintended Impact of Welfare Reform on the Medicaid Enrollment of Eligible Immigrants, Health Services Research, 39(5), (October 2004), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1361081/; and Rachel Benson Gold, Immigrants and Medicaid After Welfare Reform, (Washington, DC: The Guttmacher Institute, May 1, 2003), https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2003/05/immigrants-and-medicaid-after-welfare-reform.

[7] Uncompensated care funds must also be replenished to make up for losses in emergency care of people without health insurance, but this cost is not included in our analysis of the economic impacts.

[8]The extent of employment impact depends on the state of the overall economy, with a higher impact during times of high overall unemployment, when these programs serve as both a safety net and an automatic economic stabilizer. Since the Trump Rule would be a permanent measure, there would be periods in the economic cycle the predicted economic impact would be higher and when it would be lower.

[9] The analysis of direct loss to New Jersey was performed by Danilo Trisi of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, and the analysis of economic ripple effects was performed by Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute. See Methology section for more details.

[10] That report cites as the underpinning for this range of estimates: Neeraj Kaushal and Robert Kaestner, “Welfare Reform and Health Insurance of Immigrants,” Health Services Research,40(3), June, 2005; Michael Fix and Jeffrey Passel, Trends in Noncitizens’ and Citizens’ Use of Public Benefits Following Welfare Reform 1994-97 (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, March 1, 1999); Namratha R. Kandula, et. al, “The Unintended Impact of Welfare Reform on the Medicaid Enrollment of Eligible Immigrants, Health Services Research, 39(5), October 2004; and Rachel Benson Gold, Immigrants and Medicaid After Welfare Reform, (Washington, DC: The Guttmacher Institute, May 1, 2003).

[11] Josh Bivens, “Method Memo on Estimating the Jobs Impact of Various Policy Changes,” Economic Policy Institute, November 8, 2011.

[12] Any slowdown in the growth of aggregate demand caused by reductions in spending on these programs could in theory be neutralized by the Federal Reserve Bank lowering rates to spur growth. However, this does not change the size of the fiscal drag that benefit cuts would impose on the economy. These estimates are implicitly a measure of how much harder other macroeconomic policy tools would have to work to neutralize the demand drag stemming these cuts. Further, it is deeply uncertain whether other tools of macroeconomic policy have the ability to neutralize negative fiscal shocks. See Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Laura Feiveson, Zachary Liscow, and William Gui Woolston, “Does State Fiscal Relief During Recessions Increase Employment?,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, August 2012, pp. 118-145.

[13] Data for the analysis come from tables 1.1.5 and 6.5 from the National Income and Product Accounts of the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The quotient was increased by the growth in its nominal value in 2017 to forecast what it would be in 2018.