To read a PDF version of the full report, click here.

Crafting a state budget is a tricky task in the best of times as lawmakers juggle competing needs while attempting to predict future economic conditions. This year, however, the COVID-19 pandemic has turned the fairly straightforward FY 2021 budget season into one that will force lawmakers to address sudden and dramatic changes in New Jersey’s finances and the state’s broader economy.

New Jersey is facing a dual threat from the COVID-19 pandemic: a public health crisis that requires mandatory business closures and social distancing, along with the economic fallout from these necessary measures. The state is taking in dramatically less revenue in income, sales, and corporate business taxes, stretching its finances thin. At the same time, lawmakers are hoping to ramp up spending to curb the spread of COVID-19 and provide relief for workers and families struggling to make ends meet. The Murphy administration has already frozen $920 million in planned expenditures in anticipation of a significant drop in revenue collections.[1] New Jersey’s Rainy Day Fund, which is meant to offset the impact of unexpected emergencies, is not sufficient to meet the state’s pressing needs in the coming days and months. Progressive sources of revenue will be needed to ensure the state has the resources to meet our rapidly growing public health and economic needs.

Under the first two years of the Murphy administration, New Jersey has moved away from trickle-down strategies and toward progressive tax structures that enable sufficient investment in public services and assets. Unfortunately, these policies have not been in place long enough to undo decades of underinvestment, nor has there been enough progress to blunt the impact of COVID-19 on the state’s economy. By implementing new, reliable sources of revenue, state lawmakers can avoid harmful cuts to vital services, protect New Jersey families harmed during this economic downturn, and build an economy that works for the many.

New Jersey’s Revenue Problem

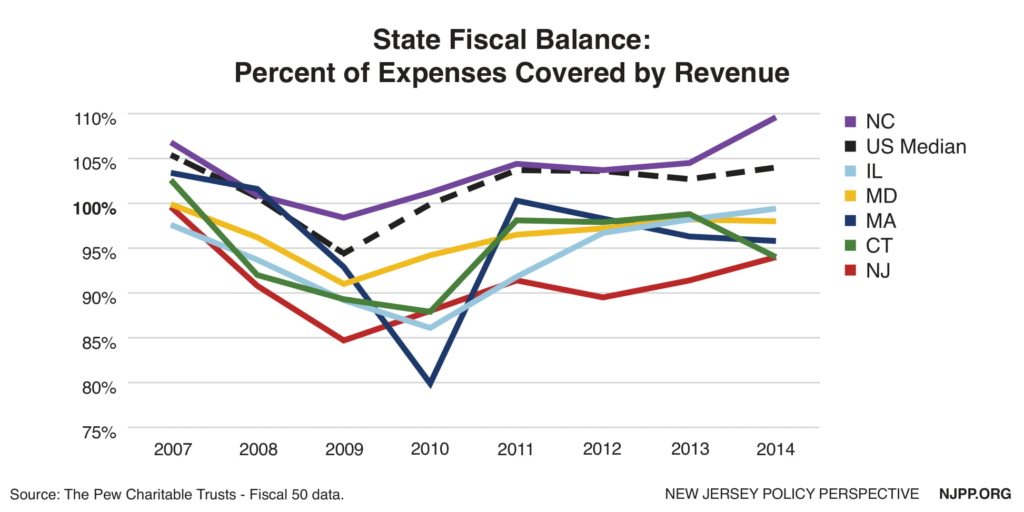

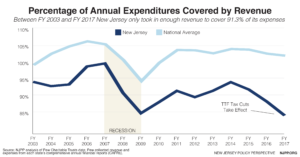

New Jersey has a revenue problem. In fact, the state has failed to bring in enough revenue to cover annual expenses since at least 2002. Looking at the latest available data, New Jersey has the worst fiscal deficit in the nation at 91.1 percent.[2]

This lack of revenue has resulted in flat funding and cuts to department budgets, the raiding of trust funds and emergency savings to make ends meet, and forgoing investments into our Rainy Day Fund. For instance, over $300 million in dedicated funds meant for the Affordable Housing Trust Fund were diverted over the course of the last decade to cover chronic budget shortfalls, severely hampering the state’s ability to construct affordable homes and address its continuing housing and foreclosure crisis. Similarly, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection has a limited capacity to hold big polluters accountable and enforce clean air, water, and waste standards as its funding was cut 35 percent since the Great Recession.[3] All in all, these fiscal decisions have not only limited the ability of state government to do its job, but have also led to an unenviable record of 11 credit downgrades by the major credit rating agencies since 2010, making borrowing for capital improvement projects more expensive.[4]

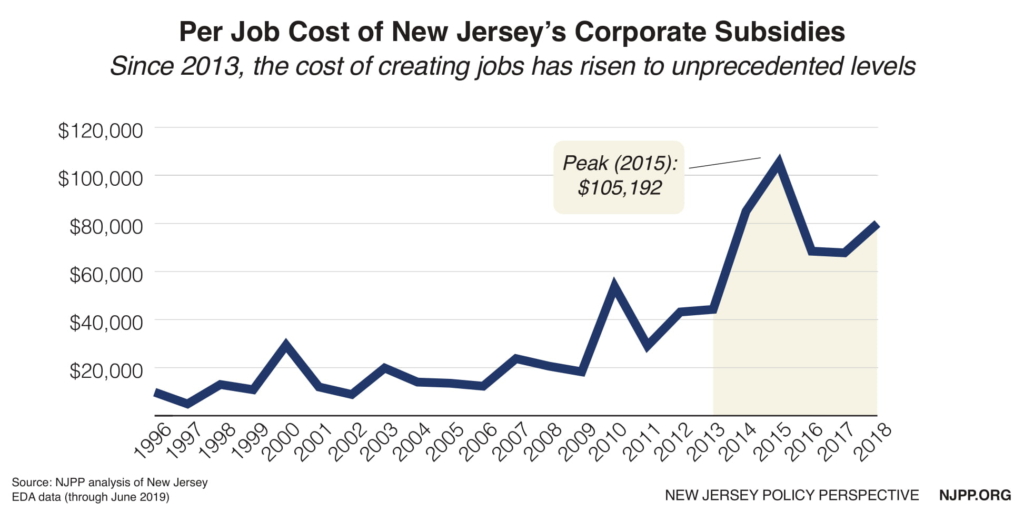

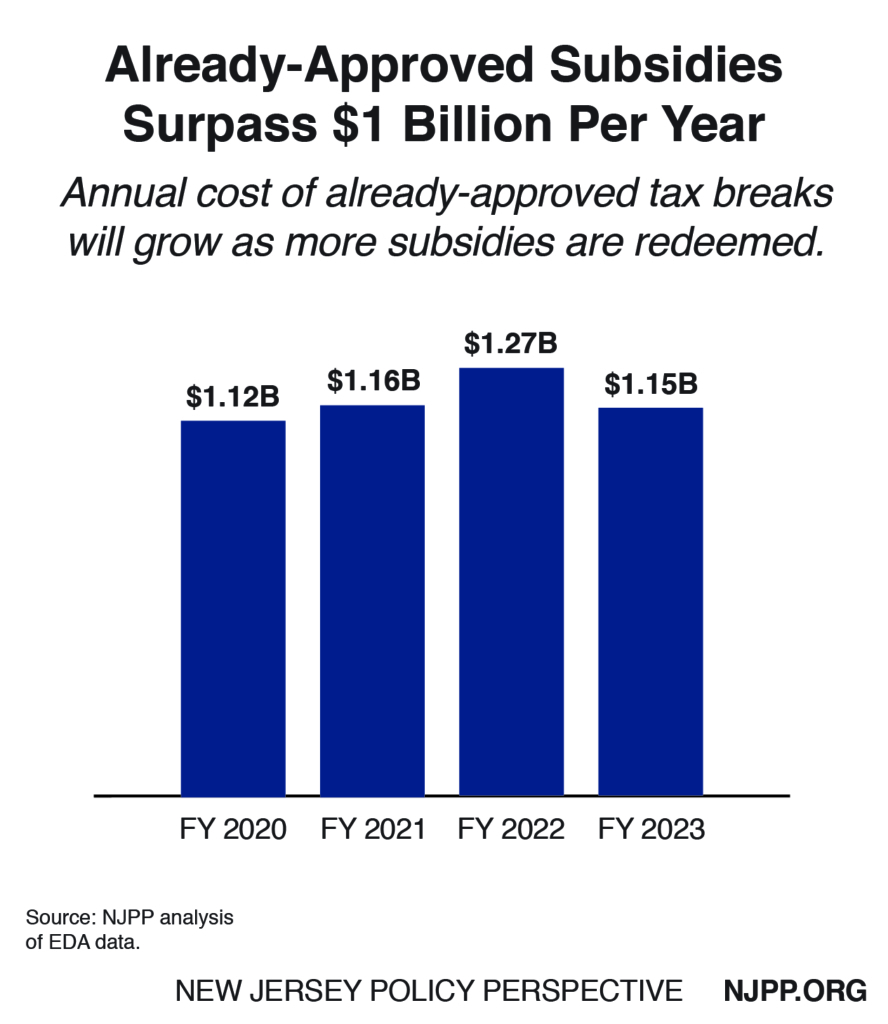

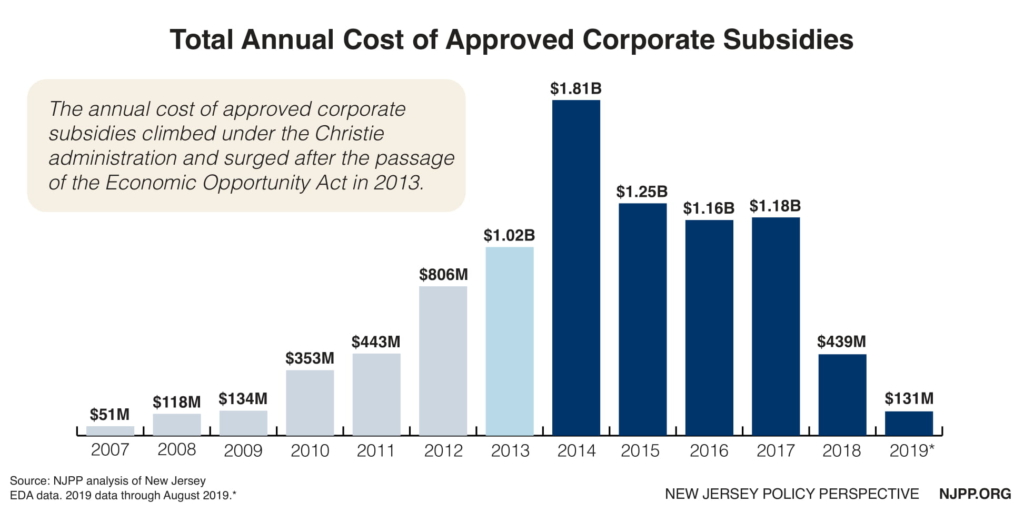

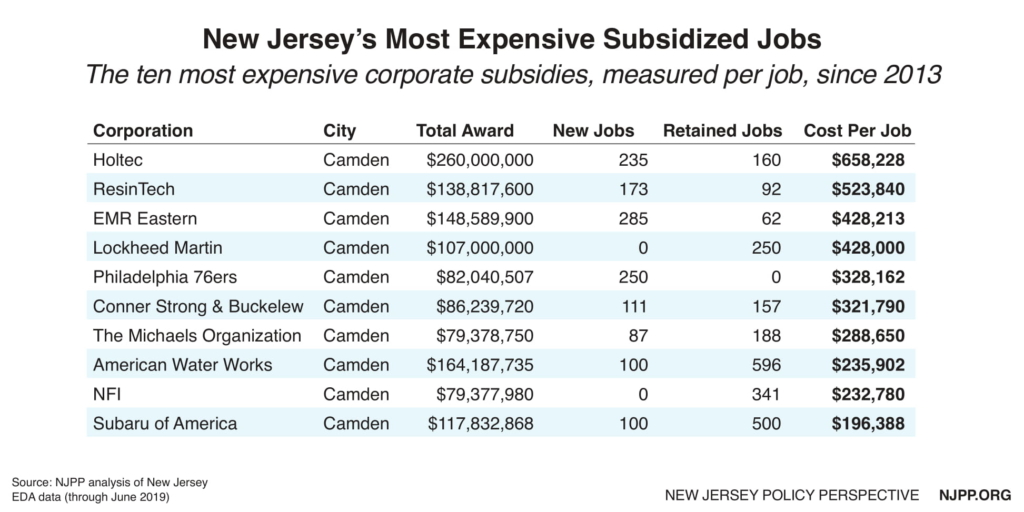

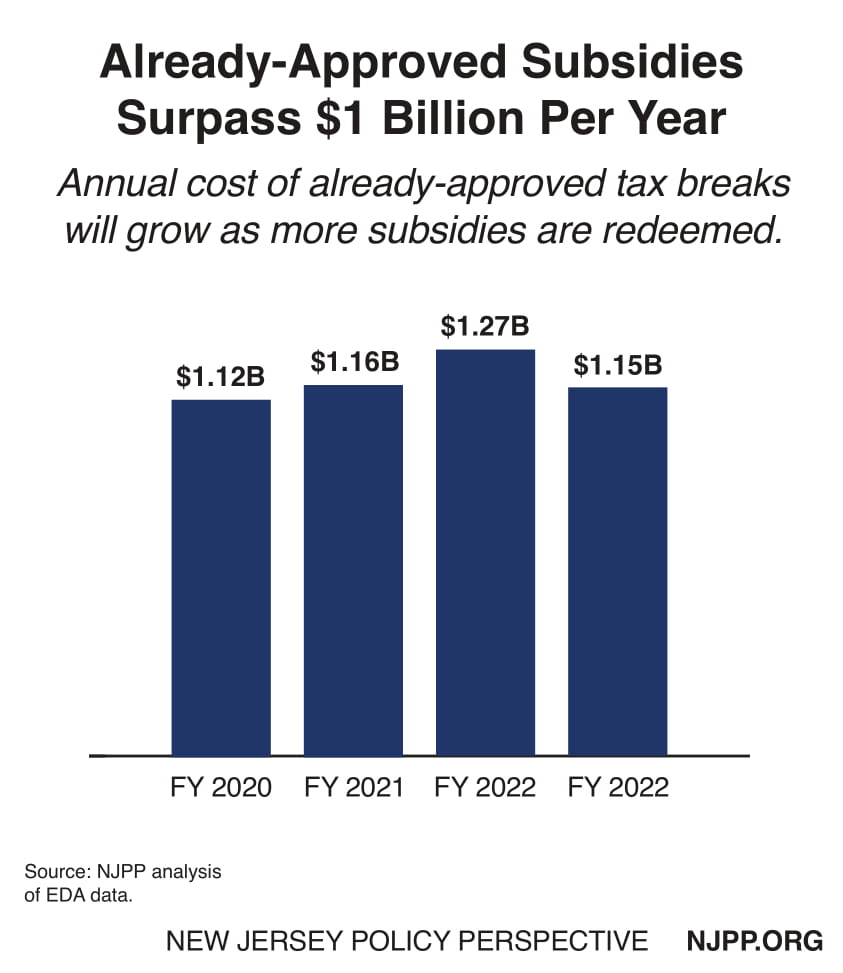

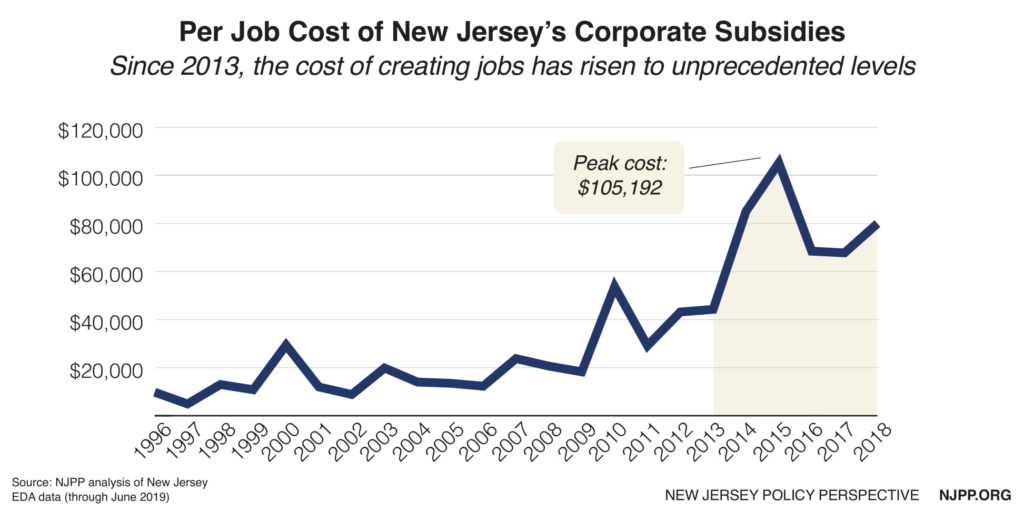

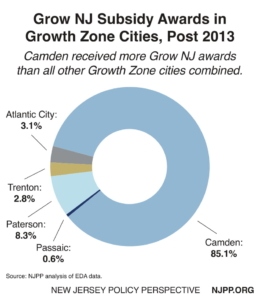

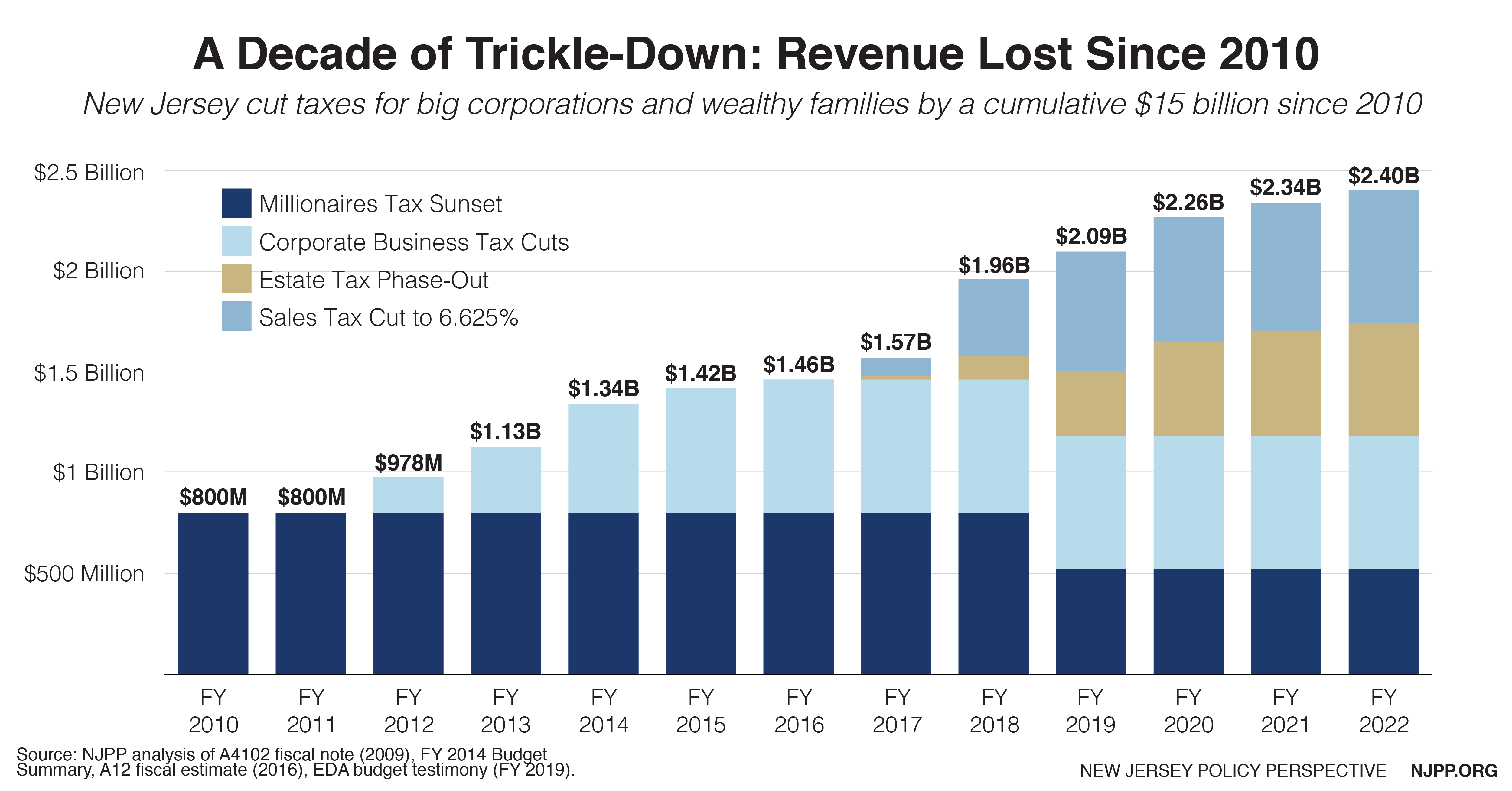

To make matters worse, the Garden State has turned its back on working families by relying on trickle-down economic policies, namely lopsided tax cuts for the ultra-wealthy and large corporations and deeply flawed economic development strategies that put a tremendous burden on the state budget for years to come. Under the Christie administration, New Jersey cut taxes and reduced revenue by a cumulative $15 billion while awarding over $8 billion in tax subsidies to already wealthy corporations.

The state’s failed experiment with trickle-down economics started in 2010 when the millionaires’ tax was allowed to sunset, giving wealthy families a cumulative $5 billion in tax breaks and undermining property tax relief programs that allow low-income seniors and adults with disabilities to remain in their homes. In 2018, the estate tax was fully repealed, which was only paid by the wealthiest 4 percent of households in the state. Since the repeal of this tax, wealthy heirs have collectively benefited to the tune of $923 million at the expense of middle-class families. What’s more, in 2017 the state began gradually reducing the sales tax from 7 percent to 6.625 percent. This small decrease in the sales tax has cost New Jersey $1.7 billion in lost revenue, making it even more difficult for the state to fund key priorities, build a healthy Rainy Day Fund, and meet its existing obligations.

These cuts also have deepened structural inequality in the very communities that have been historically deprived of meaningful investments. Already, 25 percent of New Jersey families don’t have enough savings to withstand an emergency without falling into poverty, despite the state’s ranking as one of the wealthiest in the nation.[5] It’s disproportionately worse for New Jersey’s Black households at 45 percent and Hispanic/Latinx households at 60 percent. For these families, a layoff or a visit to the emergency room can easily translate into a financial crisis.

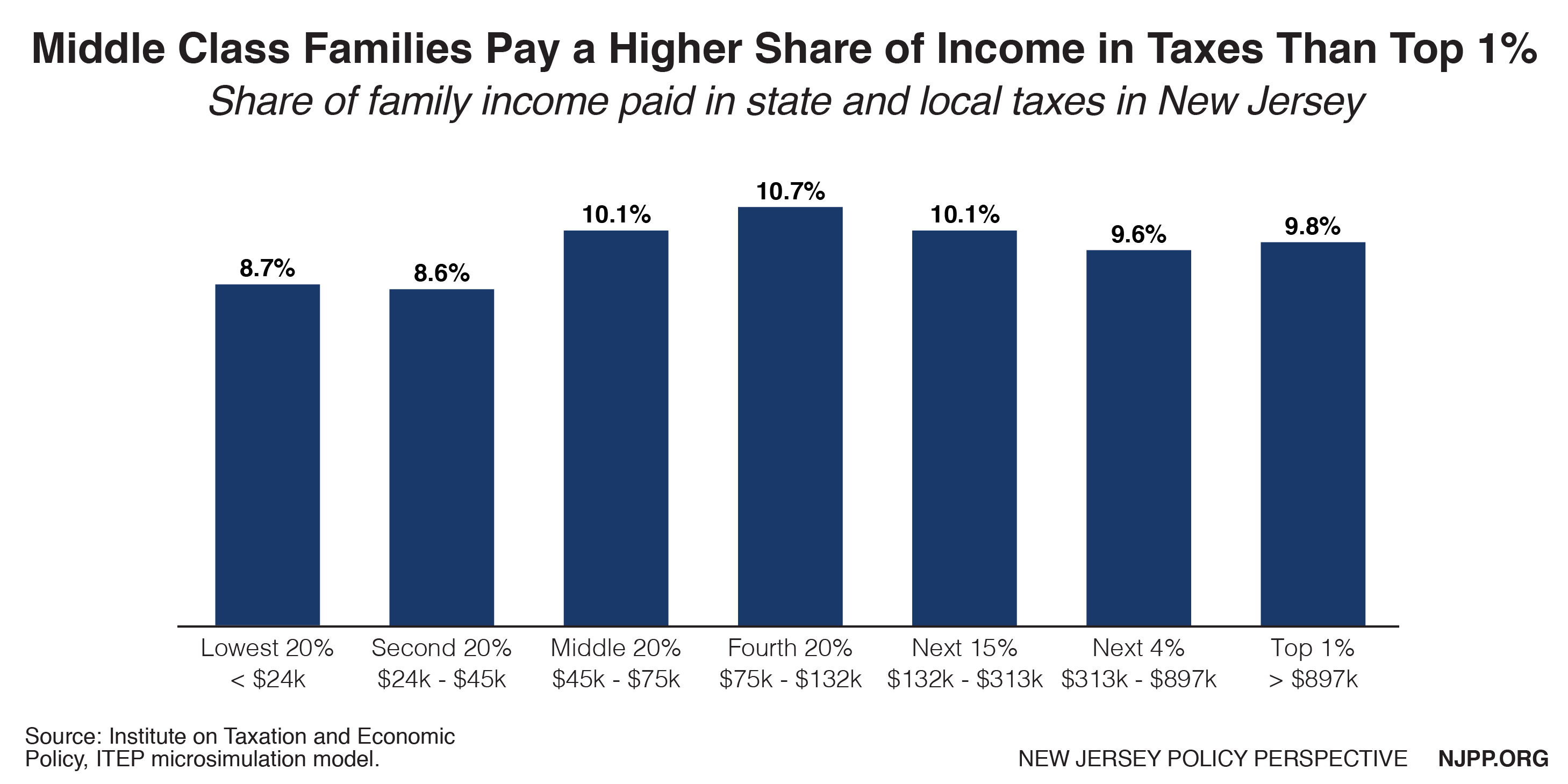

What’s worse, everyday New Jersey families now pay a higher percent of their income in state and local taxes than the state’s wealthiest households do. Middle-income earners — those who make $74,800 to $132,000 annually — pay the highest effective tax rate. They also pay the highest percentage of their annual income in property taxes, at an average of 5.8 percent. Those in the top one percent pay a much smaller share of their income in property taxes at an average of 2.2 percent. The state tax code also disproportionately harms households of color, who are more likely to earn less (due in large part to the nation’s legacy of slavery and generations of discriminatory state and federal policies), and thus pay a larger share of their incomes in state and local taxes than white households.

Breaking Bad Habits: Governor Murphy’s First Two Budgets

The first two budgets enacted under Governor Murphy’s tenure were a good start to repairing years of flat funding, raids on dedicated funds, and disinvestment across the board. Collectively, they were the most progressive budgets New Jersey has seen in at least a decade due to a commitment to tax fairness that, in turn, reinvested in key assets that create strong communities and help grow the state’s economy.

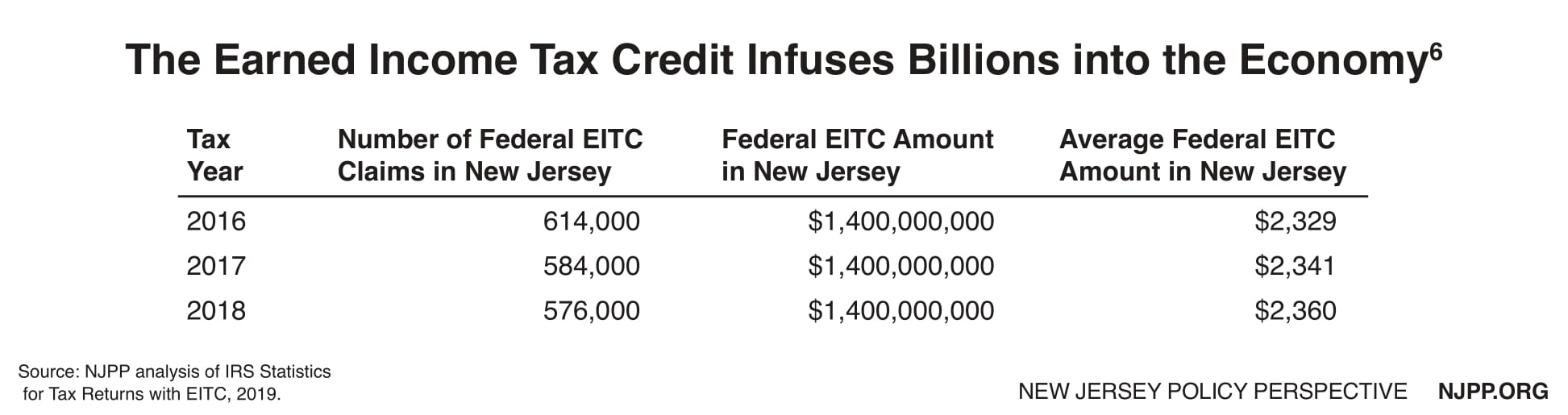

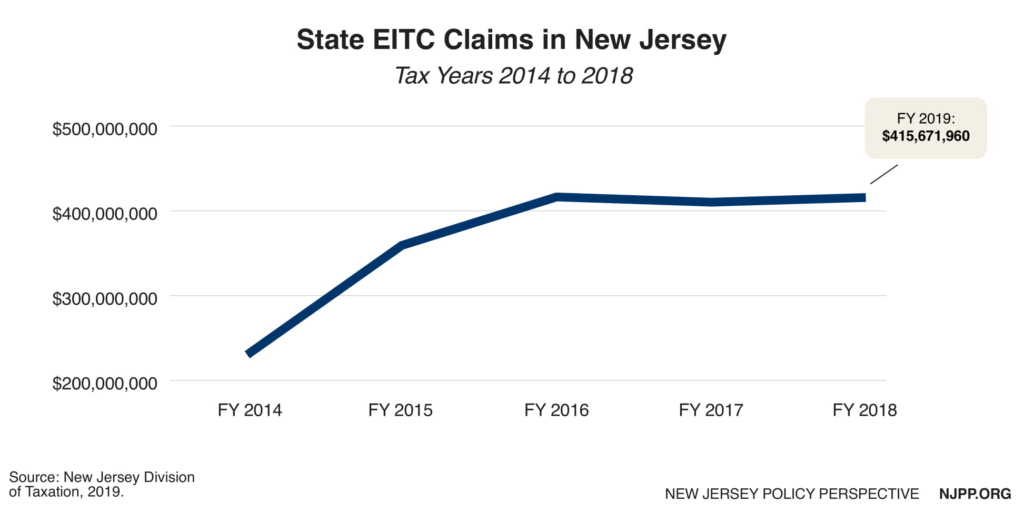

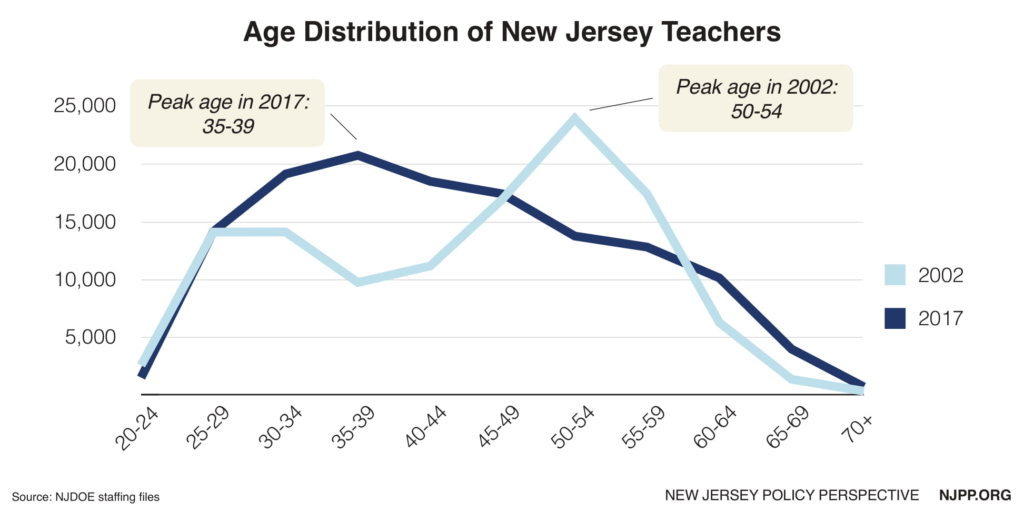

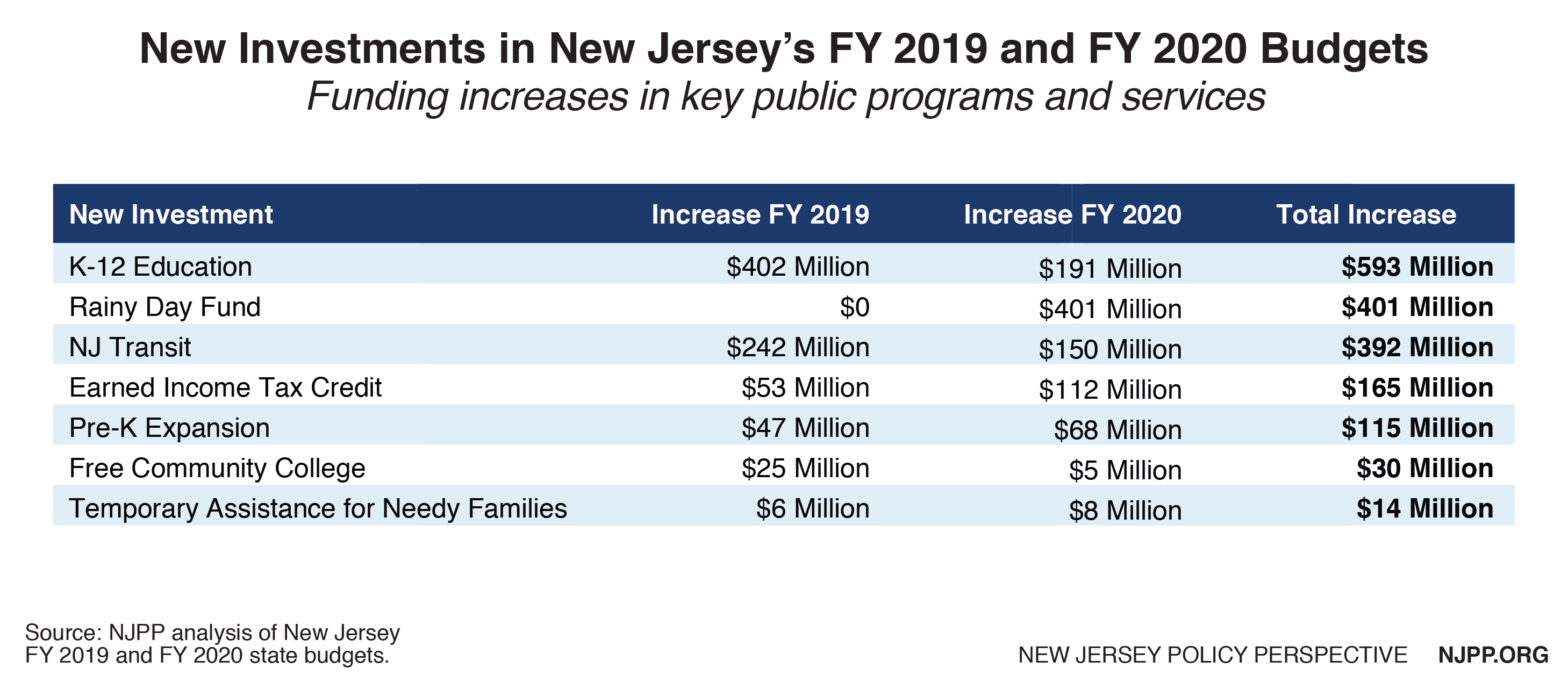

In the last two years, New Jersey made back-to-back record-breaking pension payments, protecting the retirement security of 800,000 public workers. Major investments were made in New Jersey’s most important assets like pre-Kindergarten expansion, K-12 education, and NJ Transit after years of neglect. The state prioritized working families and those struggling to get by with an expanded state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and a new Child and Dependent Care Credit for low-paid working parents. Tuition-free community college was offered for the first time, giving 18,000 low-income students a path toward a more prosperous future. Funding for property tax relief programs improved and state-funded care workers, who are disproportionately women of color, were given an overdue raise. Finally, cash assistance for families living in extreme poverty, including 20,000 children, was raised twice, by a total of 32 percent, after 30 years without an increase.

The state’s last two budgets also prioritized good faith negotiation tactics and addressed an overreliance on budget raids. Through collective bargaining, the Murphy administration successfully secured about $800 million in real and lasting savings in the delivery of public employee health care in the FY 2020 budget — a 16 percent year-over-year decrease from the previous budget. This year’s budget also moved further away from the habitual raiding of the Clean Energy Fund and the Affordable Housing Trust, boosting their funds by $70 million and $59 million, respectively.

Finally, the state made its first, long overdue deposit of $401 million into the Rainy Day Fund, which had been empty since the height of the Great Recession. Though a relatively small investment — national budget experts recommend states save 16 percent of their annual spending in reserves — it is an important step in rebuilding an emergency savings account that the state can use during tough times without having to make detrimental cuts which commonly put low-income communities of color at the most risk. Unfortunately, it is likely to be used up quickly in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

All these investments were possible due to a steady job growth rate, a stable economy, and an administration that, over the last two years, prioritized new, renewable sources of revenue after a decade of tax breaks for wealthy families and large corporations. By restoring the 10.75 percent income tax rate on earnings over $5 million (a part of the millionaires tax that sunset under the Christie administration), applying the sales tax to purchases made on the Internet, closing corporate tax loopholes, and enacting a new (but temporary) surcharge on corporate profits, New Jersey has established a more fiscally sound foundation for the future — albeit one that is now at severe risk due to the harmful effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

Regardless of the current crisis, these last two years demonstrate how a budget can promote tax fairness and help New Jersey families gain economic security by making meaningful investments in their communities. Decades of neglect cannot be fixed in just a few years, however. Many departments that provide critical services and programs remain flat-funded and the raiding of dedicated funds to fill budget holes has continued. More will have to be done to help the state rebuild its assets and invest in long-term initiatives again.

Looking Ahead to FY 2021: Governor Murphy’s Budget Proposal

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Governor Murphy’s FY 2021 budget proposal relied on healthy economic growth and adequate resources to fund new investments. That view has now shifted significantly to mitigating harm from a once-in-a-lifetime public health crisis while providing critical economic relief for workers, families, and small businesses.

As is, the $40.85 billion proposal commits to making substantial investments in affordable housing, education, and NJ Transit, as well as expanding programs designed to address racial, gender, and economic disparities. Like previous budgets under Governor Murphy, the FY 2021 proposal restates the importance of budgeting responsibly by scaling back on raids of dedicated funds, making the next scheduled pension payment in full, and growing a healthy surplus and Rainy Day Fund to better weather unexpected shortfalls without resorting to damaging cuts.

The Murphy administration and legislative leaders must now find a way to retain the overarching values of this proposal without shortchanging measures most needed during this pandemic. It is imperative that the state continue to adequately fund essential services to protect public health and provide relief to all affected workers and local businesses. The state’s modest Rainy Day Fund will be wiped out almost immediately, leaving it in no shape to handle immediate emergency needs. To sustain current needs, prop up the state economy, and reduce the harm to families and communities, Governor Murphy has requested at least $20 billion in aid from the federal government as part of a $100 billion multi-state package.[6] As of this writing, the federal government has provided $3.44 billion in support to New Jersey.[7] It seems that most, if not all, of the relief package is meant for COVID-19 specific interventions rather than helping New Jersey replace lost revenue due to the burgeoning economic recession. Regardless, if the state is to successfully tackle these challenges, the federal government will need to provide much, much more economic relief that is flexible for New Jersey to use as it needs. Only then can New Jersey policymakers begin to piece together a state budget that meets the needs of families and communities without making dramatic cuts during these extraordinary times.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, New Jersey is going to have to think outside the box. The effects of this crisis on New Jersey’s economy will create major upheaval for the state budget due to a surge in demand for public services just as multiple sources of revenues needed to fund them begin to evaporate. Federal support for NJ Transit and COVID-19 response has been approved, but without knowing how long this public health crisis will last, New Jersey’s fiscal outlook is precarious at best. Policymakers have a choice: either prioritize and increase resources to protect the most vulnerable New Jersey families or continue giving massive tax breaks to the well-connected.

In these challenging times, it is more important than ever that New Jersey resist the impulse to cut vital programs and services. That would be a repetition of the mistakes made during the Great Recession, mistakes which slowed the state’s recovery and set it further back.[8] Raising revenue in a progressive manner is crucial to having the resources for a proper emergency response. Without additional revenue, the state won’t be able to fully assist workers, families, and businesses who are vulnerable to economic calamity during this crisis.

In order to provide critical relief, state lawmakers should prioritize and even expand existing programs that can support and protect frontline workers like first responders, health care providers, childcare staff, and those employed by businesses providing essential services like groceries and garbage pick-up. Workers who may not qualify for federal assistance because they lack income tax filing information must also be given priority. Programs that are best positioned to protect vulnerable households from losing their home or going hungry need to be protected. Extra funding will be needed to mitigate the spread of the virus among the incarcerated and the homeless population, too. All programs that make public colleges and universities more affordable must also be spared. College tuition aid and grants for community colleges play a critical role during an economic downturn, helping jobless workers expand their skills now for economic prosperity in the future.

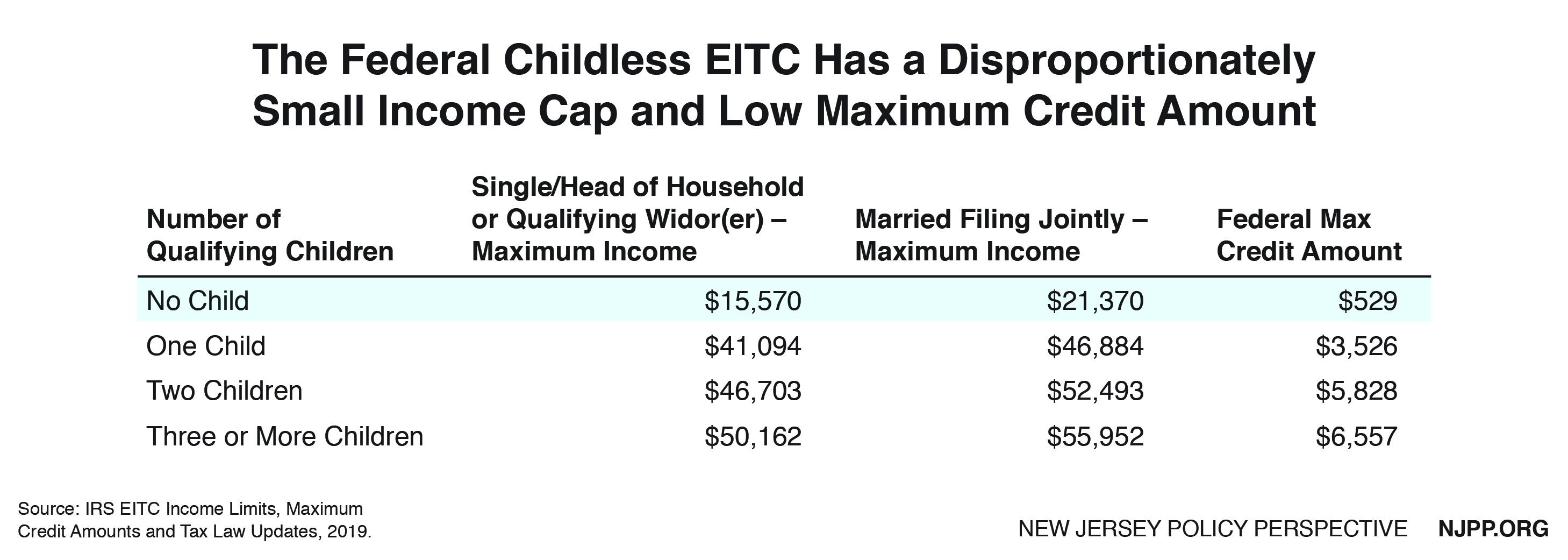

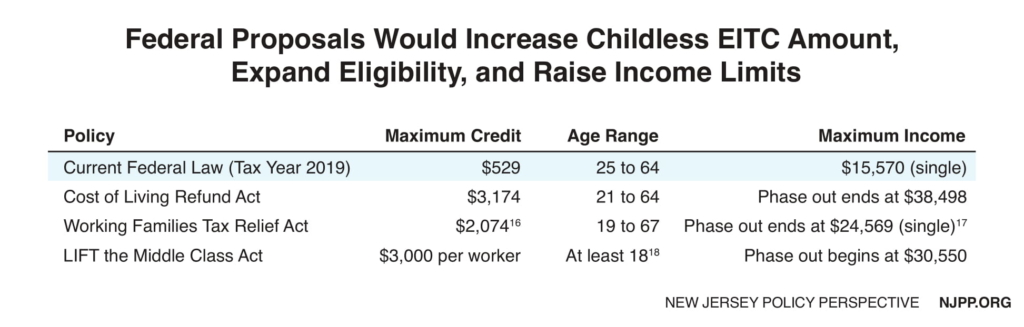

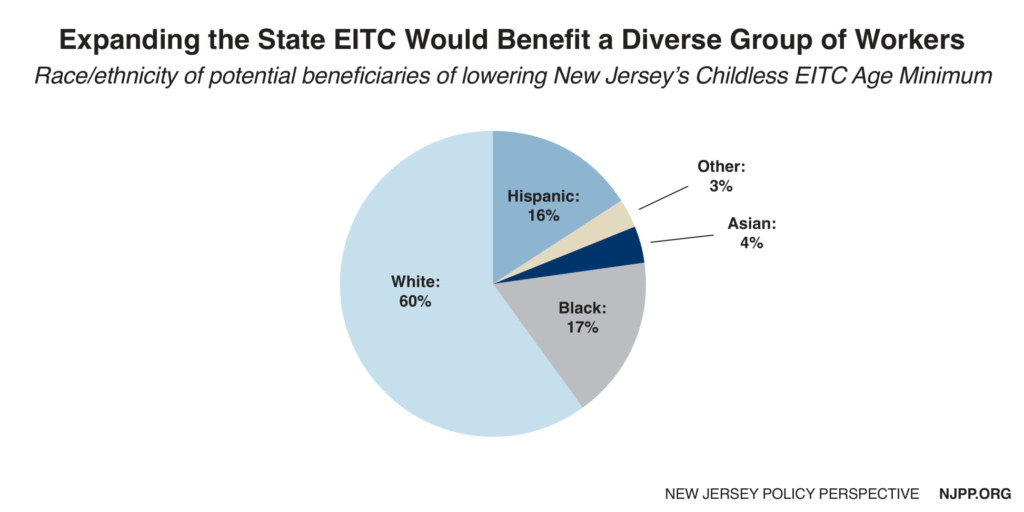

The next state budget must prioritize tax policies that deliver very targeted benefits to families most in need. The scheduled increase of the state’s EITC to 40 percent must remain in place as should plans to expand the eligibility to young adults without children.[9] It would also be prudent to establish a state-level child tax credit, designed to help working parents meet the costs of raising children, during this time of economic instability. The lack of a robust social safety net is precisely why so many families are at increased risk by the economic fallout brought on by COVID-19.

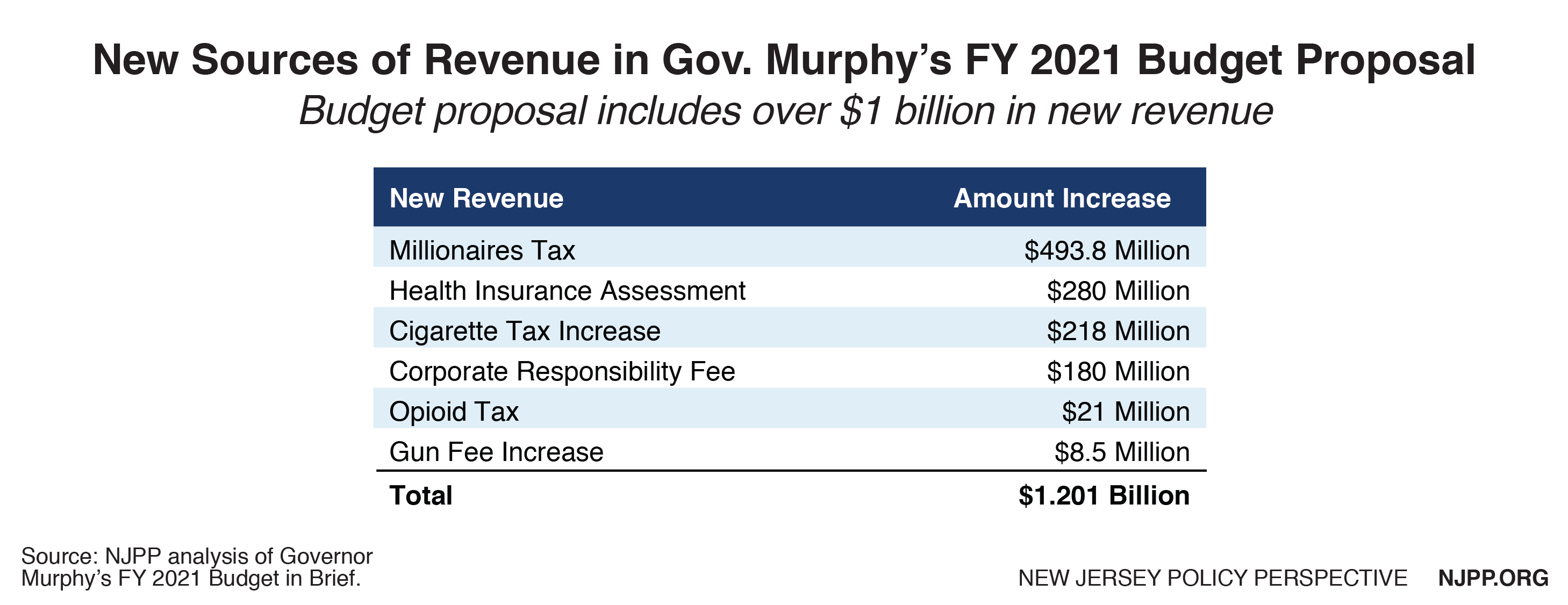

Lawmakers must table all efforts to cut taxes and instead focus on relief for those most in need by generating short- and long-term tax revenue from those who are in the best position to contribute: wealthy households and successful corporations. The Governor’s proposed budget, although crafted before the coronavirus pandemic, includes $1.2 billion in new sources of revenue through a true millionaires tax and a variety of fees and sin tax increases. To mitigate the harms posed by the current crisis, reverse revenue shortfalls, and enhance widespread prosperity and racial equity, the state must continue to prioritize responsible and progressive budgeting practices to overcome the current challenges. The proposed package of tax reforms is a good start, but it could and should go further.

For example, Governor Murphy has proposed applying the 10.75 percent income tax rate to earnings over $1 million — a 2-cent increase on every dollar earned over $1 million — to raise an additional $500 million in annual revenue. There is, however, a better way to make the income tax code more accurately reflect the lopsided income gains made by the top 15 percent of households over the past 40 years. Under the current tax code, individuals earning slightly over $75,000 are in the same bracket as those who earn just under $500,000. Creating new brackets between $250,000 and $2.5 million would make the tax code fairer and ensure budgets are not balanced on the backs of middle-class families. Further, New Jersey lawmakers should increase the marginal tax rate on annual incomes over $5 million. These changes would raise twice as much revenue as Governor Murphy’s proposal for property tax relief, school funding, and municipal aid.[10]

Governor Murphy’s proposed budget also contains a new health insurance assessment.[11] This was previously levied by the federal government but was repealed as part of the 2017 federal tax cuts. Governor Murphy’s budget estimates the new state-level policy would generate $280 million in its first year, the majority of which would support subsidies for New Jerseyans purchasing health insurance. This new revenue source is slated to generate up to $500 million annually after FY 2021.

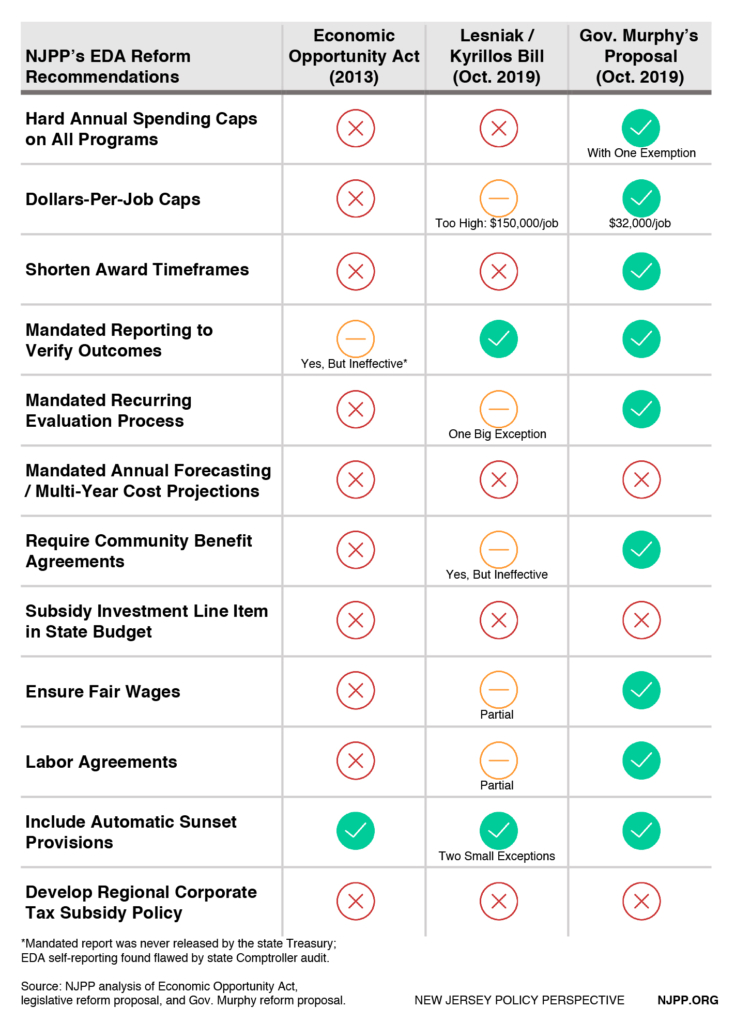

The Governor also proposed a tiered fee for private employers that have more than 50 employees receiving state Medicaid benefits. The fee is designed to encourage large corporations to improve the quality of their health benefits and reduce their reliance on state resources. However, national budget experts warn this untested policy may only encourage employers to resort to a variety of tactics to avoid the fee, potentially leading to discriminatory hiring practices and lay-offs that would disproportionately impact people of color, single mothers, and young workers.[12] There are other more-direct and proven ways to ensure large corporations are paying their fair share in taxes. New Jersey could instead raise revenue through extending the 2.5 percent corporate business tax surcharge, closing tax avoidance loopholes, and reversing business tax cuts made in 2013.

There are multiple sources of revenue that must be put back on the table during these extraordinary times. Here are other policy recommendations to consider:

- Revise taxation on inherited wealth to reverse the $500 million in tax breaks now going to wealthy heirs.

- Repeal the 2016 sales tax cut and broaden the sales tax base by including services typically utilized by wealthy households, such as limousine services and chartered flights.

The purpose of fair taxation is to raise revenue in an equitable manner that can fund the critical public services and assets New Jersey families rely on with enough left over to save for a rainy day. A progressive tax code is also crucial to improving racial equity and undoing centuries of discrimination that have left communities of color behind,[13] making them particularly vulnerable during moments of crisis.[14] Unfortunately, New Jersey spent the last decade largely ignoring these important priorities. Had the state spent that time making annual investments in the Rainy Day Fund that match what it made last year, we would have nearly $4 billion to help tackle the COVID-19 crisis instead of the $401 million currently available. Going forward, implementing sound tax policies that help the state plan for future challenges will be paramount.

New Jersey’s economic future is at risk with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the associated economic fallout from social distancing measures, and the uncertain amount of federal assistance New Jersey will ultimately receive. Workers, families, and businesses need real help and the state needs to prepare and act quickly. State lawmakers simply cannot afford to fall back on old habits by cutting government services and waiting out the storm. New Jersey needs new, reliable sources of revenue to build up a healthy surplus, avoid harmful cuts to vital services, and protect those most at risk during this economic downturn. Only then can we say with confidence that our state budget lives up to the values we all share and hold dear.

End Notes

[1] Office of the Governor, Treasury Freezes Nearly $1 Billion in Spending as Fiscal Uncertainty Over COVID-19 Mounts. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/approved/20200323g.shtml

[2] The Pew Charitable Trusts analysis of each state’s comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs) and converted to 2017 dollars. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2014/fiscal-50#ind9

[3] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Annual Appropriations Act FY 2008 – FY 2020, adjusted for inflation in 2019 dollars. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/legislativepub/finance.asp

[4] The State of New Jersey, The Governor’s FY 2019 Budget in Brief, March 2018. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/19bib/BIB.pdf

[5] 2016 Survey of Income and Program Participation in Prosperity Now’s Scorecard: Data by Location: New Jersey, Outcome: Liquid Asset Poverty, Data by Race. https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-location#state/nj

[6] Governor Phil Murphy Press Release, Regional Coalition Requests a Direct Cash Assistance Program of At Least $100 Billion in Response to Financial Impact of COVID-19, March 2020. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/approved/20200320b.shtml

[7] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, How Much Each State Will Receive From the Coronavirus Relief Fund in the CARES Act, March 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/how-much-each-state-will-receive-from-the-coronavirus-relief-fund-in-the-cares-act

[8] New Jersey Policy Perspective, In Brief: Preparing New Jersey for the Next Economic Downturn, November 2019. https://www.njpp.org/budget/in-brief-preparing-new-jersey-for-the-next-economic-downturn

[9] NJ BIZ, Murphy admin proposes ramping up tax credit for NJ’s lowest-earning residents, February 2020. https://njbiz.com/murphy-admin-proposes-ramping-up-nj-earned-income-tax-credit-for-lowest-earning-residents/

[10] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Treasury and income tax data.

[11] NJ Spotlight, Murphy Budget Includes Taxes, Spending to Combat ACA ‘Sabotage’, February 2020. https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/02/murphy-budget-includes-taxes-spending-to-combat-aca-sabotage/

[12] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Proposal in NJ Governor’s Budget for Medicaid Fee Proposal Would Create Unintended Incentive for Job Discrimination, Harm Workers, February 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/new-jersey-governors-medicaid-fee-proposal-would-create-unintended

[13] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Advancing Racial Equity With State Tax Policy, November 2018. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy

[14] Center for American Progress, The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Racial Wealth Gap, March 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/news/2020/03/19/481962/coronavirus-pandemic-racial-wealth-gap/