All children in New Jersey deserve the freedom to grow up safe, healthy, and free from poverty. Childhood poverty hurts school performance and growth today, while damaging mental and physical health and earning power for a lifetime. Research is clear: childhood poverty causes lasting harm. Yet 1 in 8 New Jersey children still live in poverty ($32,000 for a family of four).[1] This level of deprivation should not be tolerated in one of the wealthiest states in the wealthiest nation in the history of the world.

This report plots a bold way forward for New Jersey to lead the nation in ending child poverty and ensuring all families have what they need. The report outlines two paths forward:

- Expanding and improving existing anti-poverty programs, and

- Creating a new child allowance program for children in low-income families.

This vision is not new. For generations, leaders across the globe have argued that true freedom requires freedom from poverty. In his Four Freedoms speech from more than 80 years ago, President Franklin Roosevelt said that free nations should provide “freedom from want” for their people, to secure a “healthy peacetime life” for all.[2] The United Nations Declaration of Human Rights echoes this, promising an adequate standard of living for all people to have food, clothing, housing, medical care, and social services.[3] While the United States lags behind, almost all wealthy countries provide a child allowance as a basic income floor for households with children.[4]

The federal government has pulled back from helping low-income and working families.[5] Now states like New Jersey must step up and show how economic growth can coexist with economic security for those who need it most.

Key Findings

New Jersey has the resources to dramatically cut child poverty. It has one of the nation’s highest median household incomes at nearly $100,000 annually.[6] Its economic engine generates enormous wealth, with its gross domestic product rivaling global powers.[7] And New Jersey has a base of existing anti-poverty programs to build from, such as the state Child Tax Credit and state Earned Income Tax Credit.[8]

The latest lessons in anti-poverty programs come from “guaranteed income” pilot programs, which have provided unrestricted cash to families and individuals seeking economic stability. These programs stand out for their simplicity: by removing red tape and government paperwork, guaranteed income pilots trust individuals and families to make their own choices about how to spend assistance. The results of these pilots have been impressive: lower poverty, higher academic achievement, and greater food and housing security.[9]

|

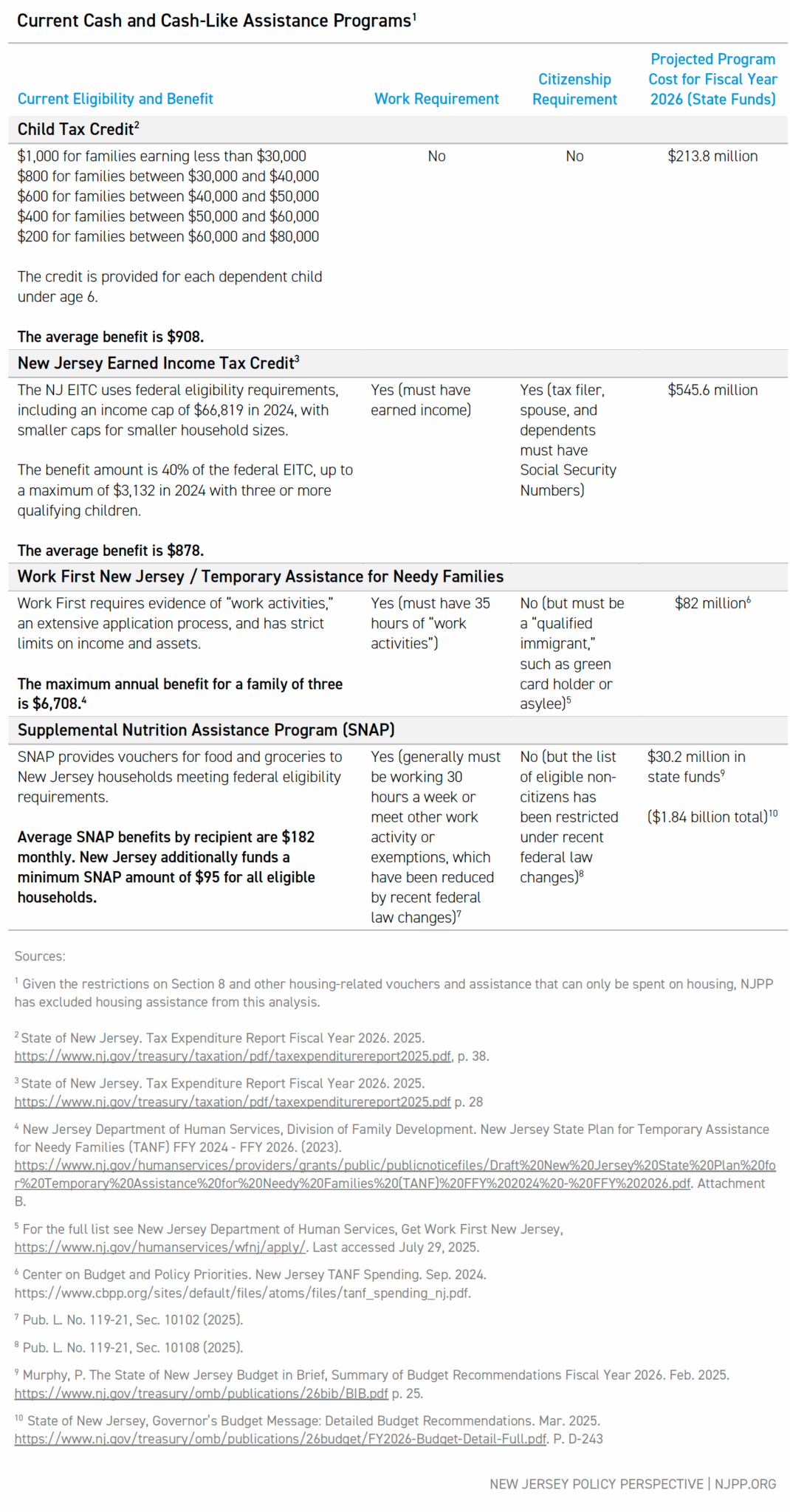

Building on these lessons, this report offers two paths forward for New Jersey to move closer to a world without want for its children and families: Path 1Expand New Jersey’s existing family affordability programs to provide more cash to more families with less red tape. Currently, New Jersey operates four main anti-poverty programs with cash or cash-like assistance:

This plan would double the benefit amounts for the tax credit programs and Work First New Jersey to bring them in line with the standard of living in New Jersey. An additional monthly payment would be added to SNAP using state funds. Path 2Create a new program, the New Jersey Family Guarantee, which would provide $5,000 annual payments to families of Medicaid-eligible children. Rather than work through existing programs, this more ambitious proposal would lay the groundwork for a more robust child allowance program in New Jersey, allowing all children eligible for Medicaid (or whose births were covered by Medicaid in New Jersey) to receive annual payments of $5,000 to help support their upbringing and well-being. The two proposals would require significant investment by the state, but would be well within the scope of other state cash assistance programs. The expansion proposal would cost around $1.84 billion, while the New Jersey Family Guarantee program would cost around $3.21 billion at full funding. By comparison, the ANCHOR property tax relief program costs the state $2.43 billion annually, while the state’s wide array of property tax relief programs costs $4.88 billion.[10] As these annual payments demonstrate, the state’s political leaders have shown a willingness to invest substantial state resources into direct payments for households. |

The Problem: Child Poverty’s Lasting Harm

Child poverty is not inevitable, but the result of public policy decisions that have spent too little on families. Growing research shows that child poverty leaves lifelong scars on child development and holds back children and adults from reaching their full potential. Meanwhile, other studies prove that providing cash assistance to reduce poverty also reduces these harms and improves lifelong success for these children and their families.

The Damage Child Poverty Causes

Poverty hurts how children grow and learn. No doubt focusing on learning in school is more challenging if a child goes to bed hungry or lacks clean clothes to wear. But beyond these basics, exposure to childhood poverty leads to worse mental and physical health in adulthood.[11] The stress of poverty has been shown to rewire children’s brains, raising levels of stress hormones and disrupting development.[12]

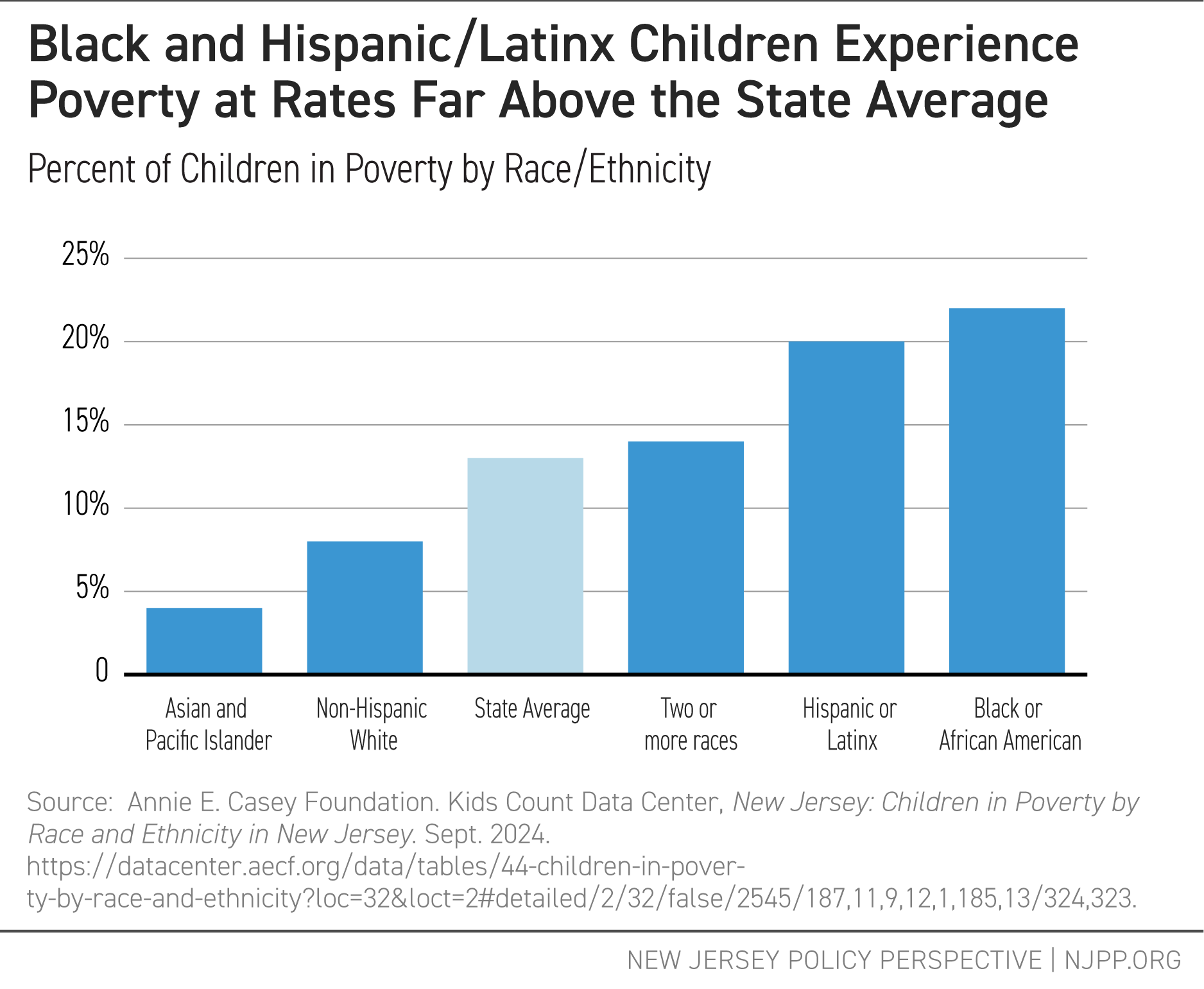

Poverty also widens and deepens gaps between Black and Hispanic/Latinx families who have been historically economically disadvantaged and their white counterparts. In New Jersey, the child poverty rate for Black and Hispanic/Latinx families is more than twice that of non-Hispanic white families.[13]

The National Academies of Sciences said it clearly in their 2019 report: poverty itself hurts children, especially when it begins in early childhood and lasts through much of childhood.[14]

New Jersey’s high cost of living compounds these harms. The official poverty rate understates the deprivation that New Jersey’s families with lower incomes experience, because the cost of housing, food, child care, and other necessities is higher than in other states.[15] Raising two children with two adults can easily cost upwards of $135,000, even as incomes fail to keep pace with those costs.[16]

The Solution to Poverty: Money

Good news: research shows the most effective way to fix poverty is simple: give people money. Cash gives people the power to make their own financial decisions and meet their needs without burdensome restrictions.

Examples include:

- The expanded Child Tax Credit as part of the American Rescue Plan provided payments of $300 per month to families across the country, reducing poverty by nearly half.[17]

- The two rounds of pandemic stimulus checks sent in 2020 during the pandemic reduced child poverty by roughly one-third.[18]

- Guaranteed income pilot programs in dozens of states and hundreds of communities, including in Newark and Paterson, have shown reductions in financial need and improvements in housing and health care.[19]

- Long-term effects from prior cash transfer programs showed not only positive academic and educational outcomes and better health outcomes, but also improvements in the next generation’s educational outcomes.[20]

Given the broad results from the research around cash programs big and small, there has never been more evidence for the effectiveness of these programs in reducing poverty. Yet in the past, programs have placed restrictions on anti-poverty programs based on racist or controlling policies, such as bans on using SNAP for prepared foods[21] or allowing only “deserving” families to receive assistance.[22]

What does cash assistance actually do? A broader cash assistance program is not a substitute for other critical supports such as health insurance, affordable housing, or public schools. Instead, research shows that cash programs help families cover basic needs, such as rent, utilities, groceries, and unexpected expenses like car repairs or medical bills.[23] The research also addresses common concerns: guaranteed income pilots have shown nearly no increase in spending on alcohol, tobacco, or gambling,[24] and little to no effect on employment, meaning people are not leaving the workforce when receiving these funds.[25]

Where New Jersey Stands Now

New Jersey already operates a series of programs that provide cash or cash-like benefits to households with children: the Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, Work First New Jersey (TANF), and SNAP. These programs each have differing benefit amounts, eligibility, and regularity (lump-sum vs. periodic payments). Nonetheless, they each help reduce the burden of economic hardship on households below or near the federal poverty line, with some key limitations.

Each of these programs has limitations that prevent some eligible residents from accessing them. For example, people must file state taxes in order to receive the Earned Income or Child Tax Credits, but filing is not required for households earning less than $10,000 annually ($20,000 if married filing jointly).[26] Other restrictions, such as work requirements and citizenship restrictions in both Work First New Jersey and SNAP, make the programs less accessible for households.[27] Each extra layer of bureaucratic red tape makes it harder for families to navigate a complex web of government systems.[28]

Despite these limitations, each program puts money (or, in the case of SNAP and Work First New Jersey, cash-like debit cards) directly into the hands of families, resulting in lower poverty and improved outcomes.[29] The Earned Income Tax Credit, for example, has shown dramatic reductions in poverty for people receiving the credit while increasing employment rates.[30]

In combination, these programs provide New Jersey with an existing program structure and proven record that can serve as the basis for a more ambitious proposal to reduce poverty for all children.

Two Pathways Towards Economic Security

New Jersey has the opportunity to be a national leader in improving family affordability and reducing poverty. By learning from the lessons of the expanded Child Tax Credit and the guaranteed income pilots, New Jersey can supercharge the cash it provides to families and cut red tape, giving families the freedom and flexibility to choose how best to spend their money.

New Jersey Policy Perspective proposes two pathways to dramatically cut child poverty and expand economic freedom for families.

One pathway builds on New Jersey’s existing programs that address family affordability through cash or cash-like benefits, such as the Child and Earned Income Tax Credits, the Work First New Jersey program, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). This pathway would increase benefit amounts and simplify program access, though federal program changes may limit how much a state can improve access.

The second pathway aims to redefine what a guarantee of family affordability could look like in New Jersey by guaranteeing that the family of any Medicaid-eligible child receives an annual child allowance of $5,000 to help address the costs of raising a child. Based on prior research, such a change would dramatically reduce child poverty and would make the concept of “freedom from want” a reality for New Jersey children.

Both programs would help to advance racial equity, as children in lower-income households are disproportionately Black and Hispanic/Latinx.[31] Research around the pandemic-era Child Tax Credit expansion showed that it lowered Black-white and Hispanic-white income inequality, especially in the lowest-income ranges.[32] A 2025 report on reparations for New Jersey’s history of slavery and racial injustice included guaranteed income as one of its key recommendations, in addition to cash reparations to compensate for past injustices and baby bonds programs to reduce wealth inequality.[33]

Pathway 1: Building on Success

As noted above, New Jersey’s cash and cash-like assistance programs have made great progress towards their goals of reducing poverty, but gaps remain in their effectiveness due to the size of the benefits and state-based restrictions on the programs. Addressing each of these two issues can supercharge the poverty-fighting effects of these programs.

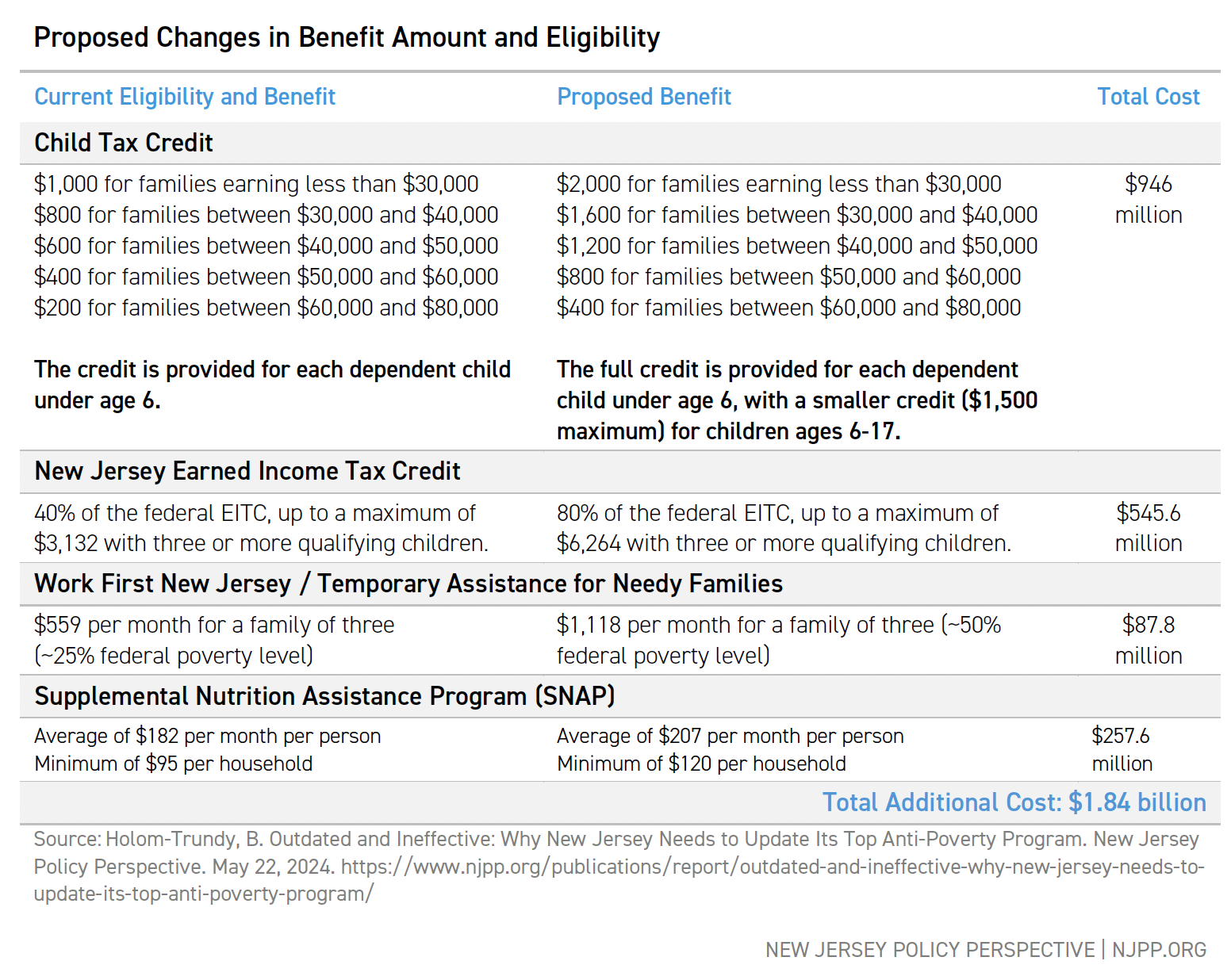

Increasing benefit amounts and eligibility

One of the lessons of the research around unrestricted cash is simple — increasing the amount of money given increases the poverty-fighting effects.[34] To that end, New Jersey can substantially increase the effectiveness of its existing programs by simply increasing the amount of money it spends.

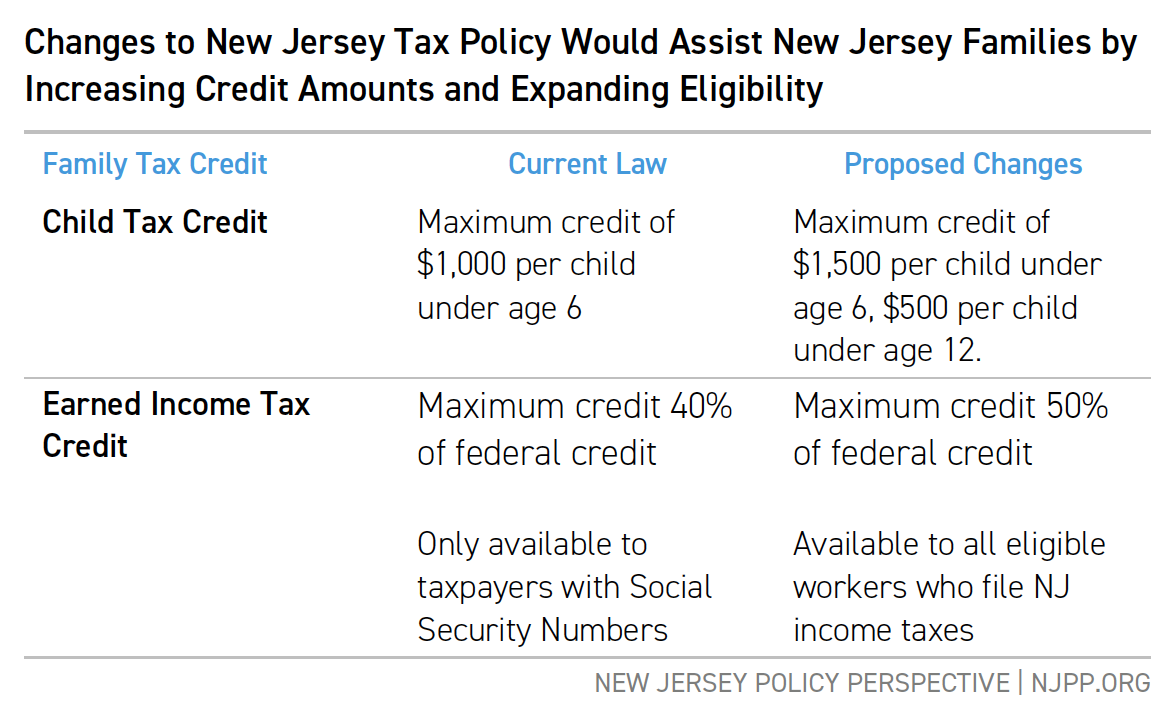

Each of these changes takes a program with an existing track record of distributing cash or cash-like benefits directly to households and increases the benefit amount to more accurately reflect the cost of living in the state. Direct cash programs (Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, and Work First New Jersey) would see a doubling of their benefit amounts, with the Child Tax Credit extending up to ages 6 through 17 at a slightly lower credit amount, with a maximum of $1,500.

For SNAP, this proposal recommends an extra payment of $25 per person per month, including an increase in the minimum household SNAP payment. This would more than double the state investment in food and nutrition assistance programs, currently set at $154.7 million.[35]

These increases would put substantially more money into family pockets and budgets, without creating new programs or administrative barriers.

Reducing red tape

Another important lesson is the damage caused by the administrative burdens of applying for programs. In New Jersey, these obstacles fall into two categories:

- Eligibility restrictions that exclude people from the program due to work, education, citizenship, or other requirements.

- Application and paperwork hurdles that make it difficult for people to apply and receive support, even if they are eligible.[36]

Eligibility restrictions.

The work requirements of Work First New Jersey and SNAP are perhaps the most prominent, limiting access to benefits only if strict employment hours are maintained. But these are not the only restrictions. Due to changes in federal law, SNAP, for instance, will now exclude refugees, people seeking or granted asylum, trafficking victims, and many other legally present immigrants.[37] Many of these restrictions are federally based and cannot easily be changed by the state.

At the state level, New Jersey has made some policy decisions that make these restrictions more difficult. The Work First New Jersey program retains a legacy of prior program decisions that cut off the program from access. NJPP has long pushed for fixes to some of these restrictions, such as:

- Eliminating barriers to participation for individuals taking college classes

- Smoothing the “off-ramp” for families to reduce the cliff effect when benefits suddenly end, putting families back into economic insecurity

- Aligning asset rules with other social safety net programs.[38]

Application and reporting hurdles.

New Jersey has taken strides to try to simplify the process, using a more streamlined online application. For SNAP, New Jersey has already used most of the flexibility available from the federal government to make the application easier for applicants, by extending eligibility certification windows and time limits, simplifying reporting, and enacting simplified eligibility.[39]

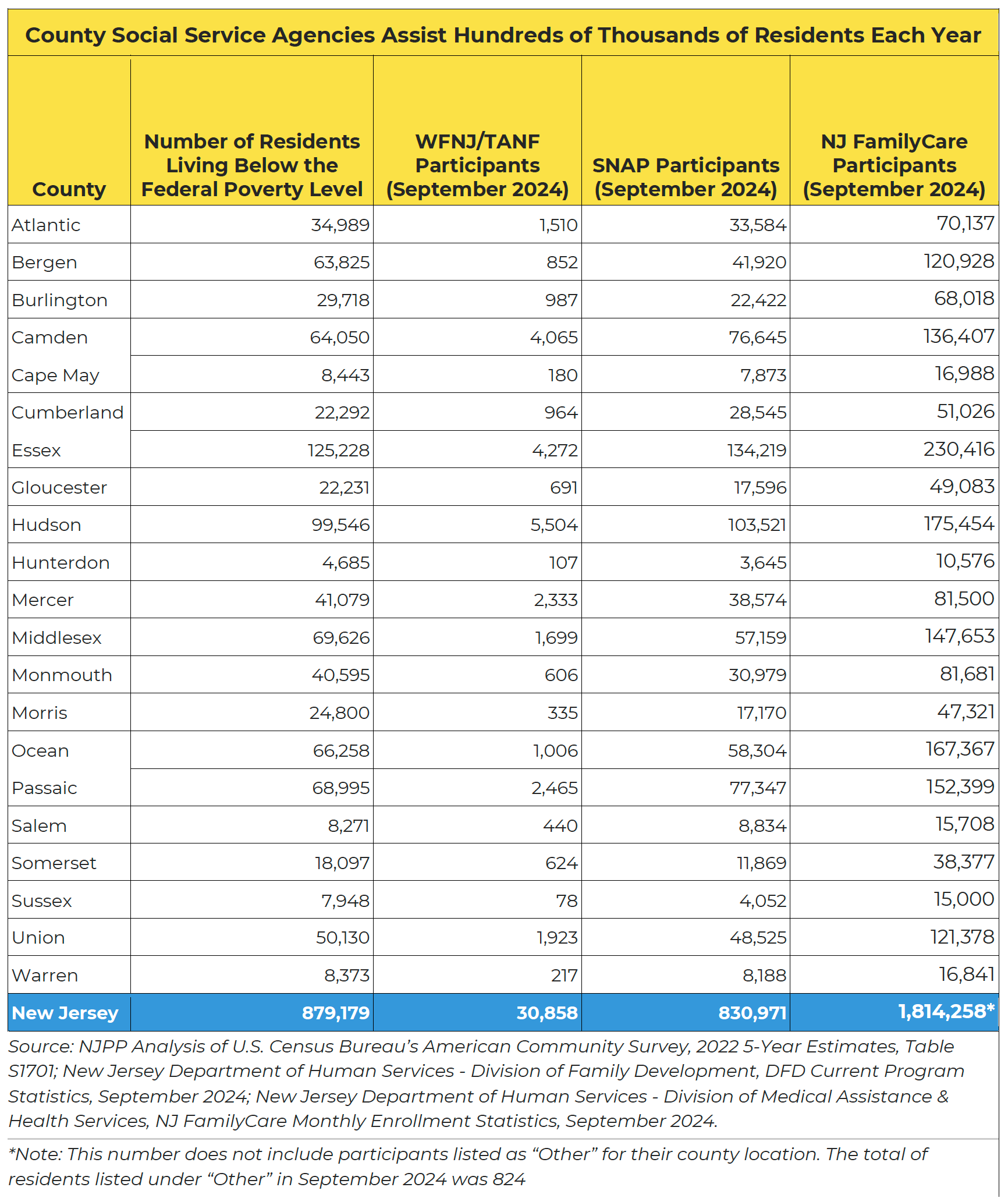

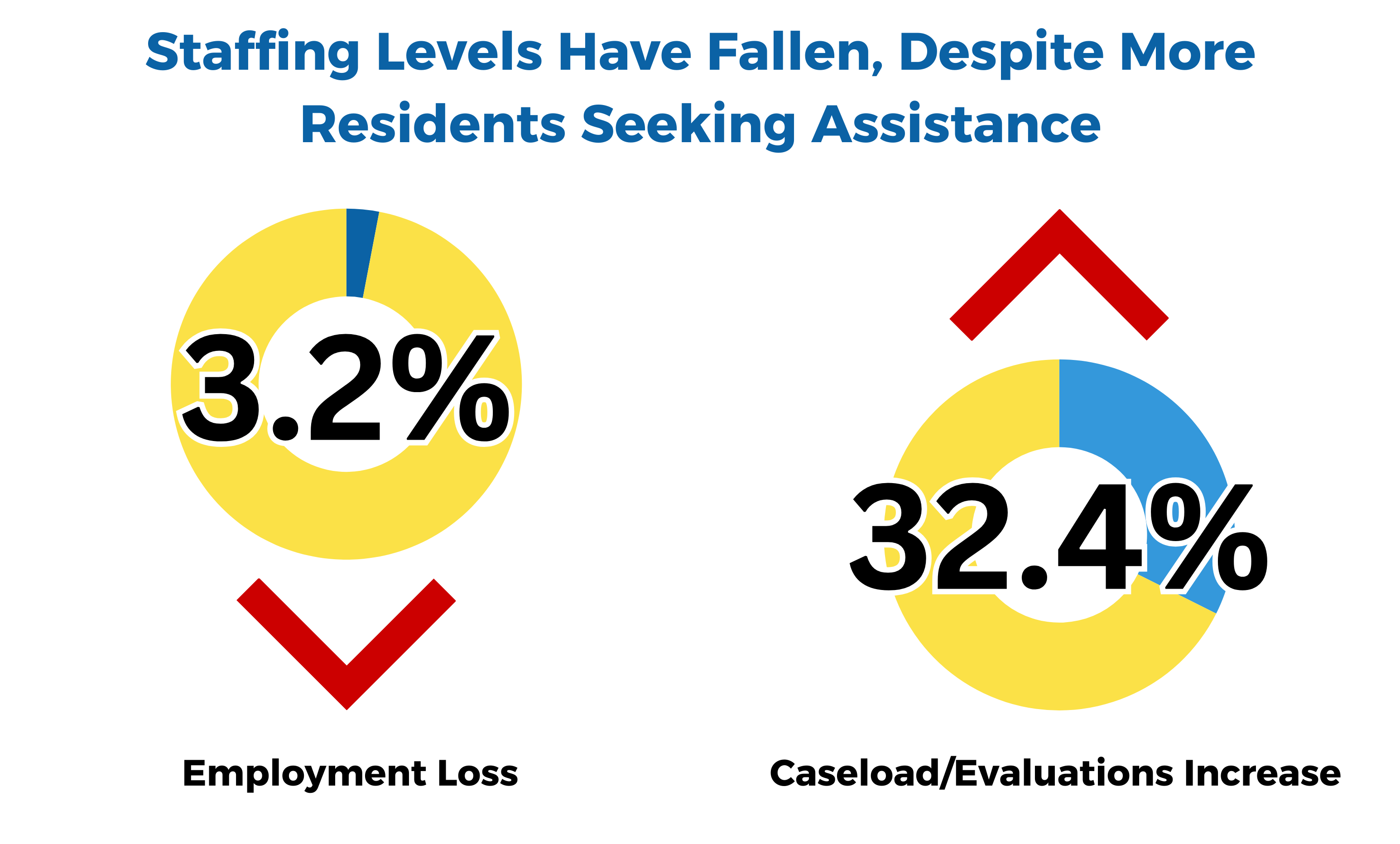

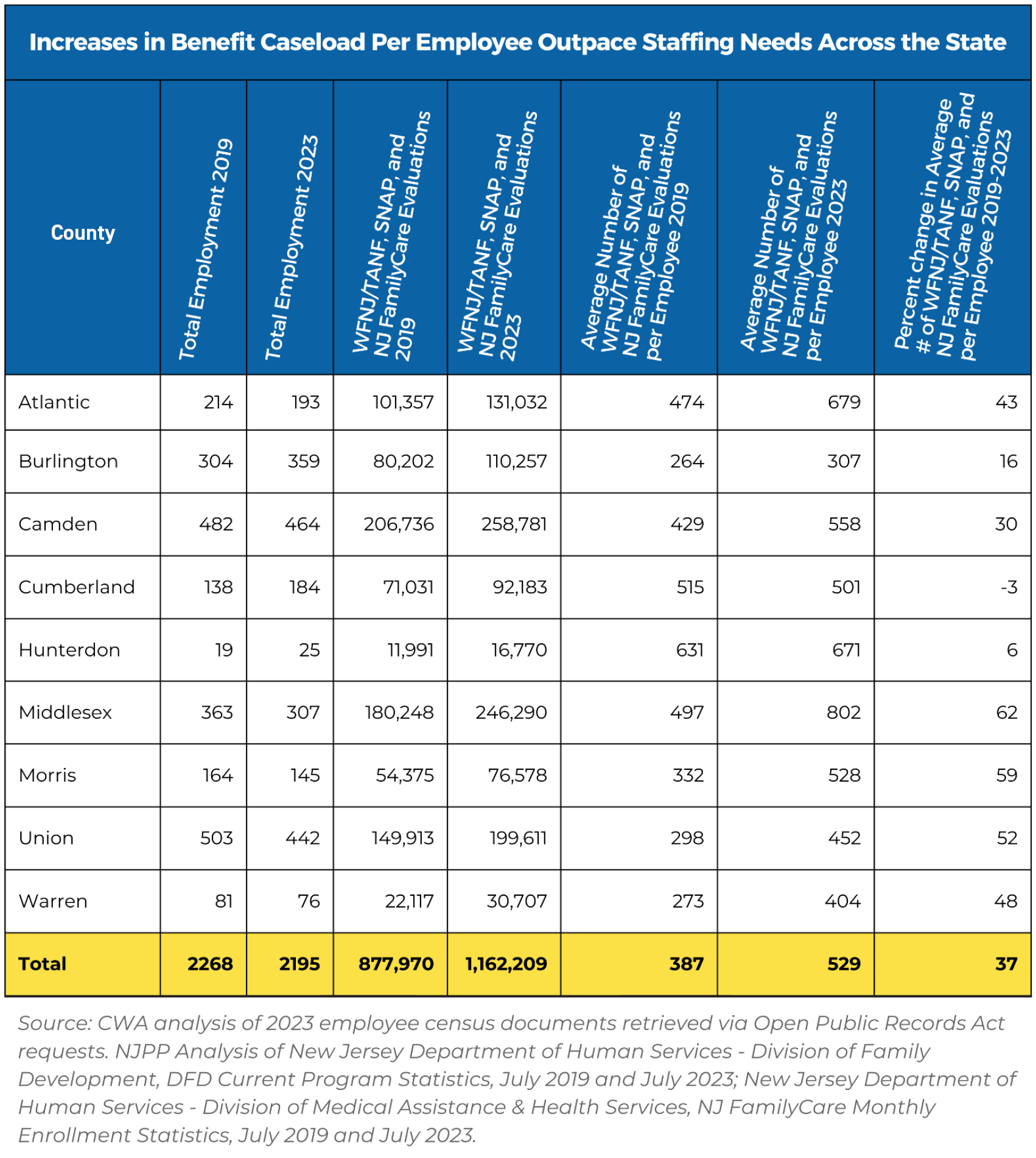

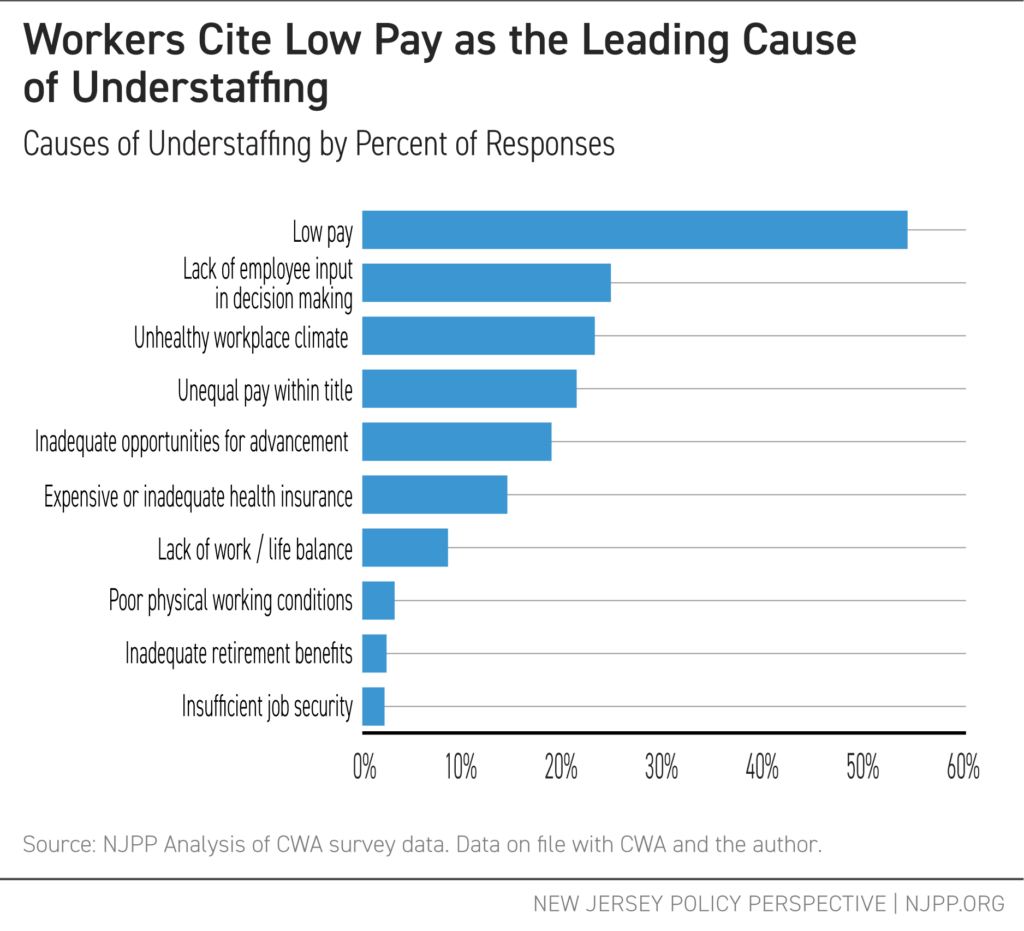

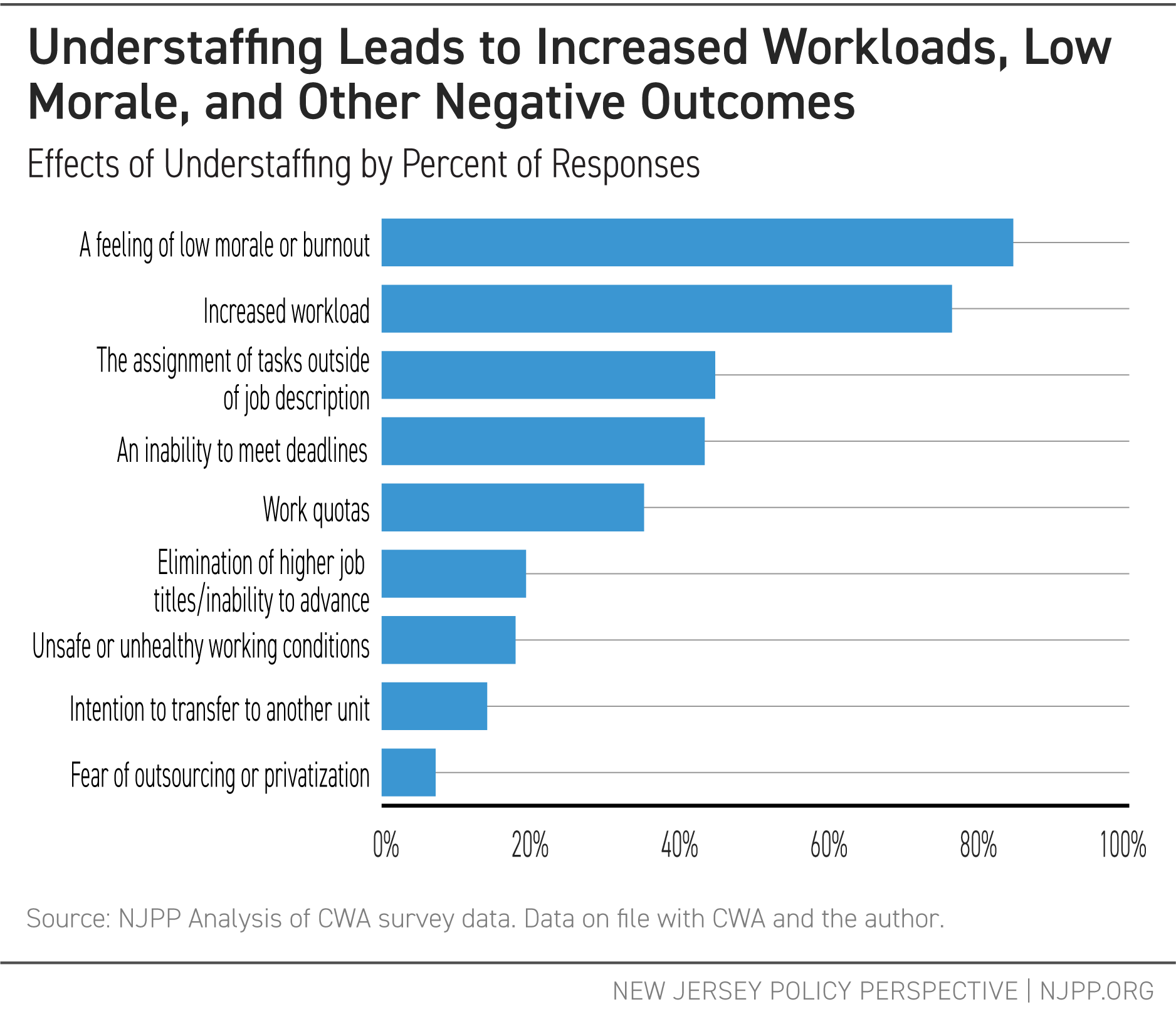

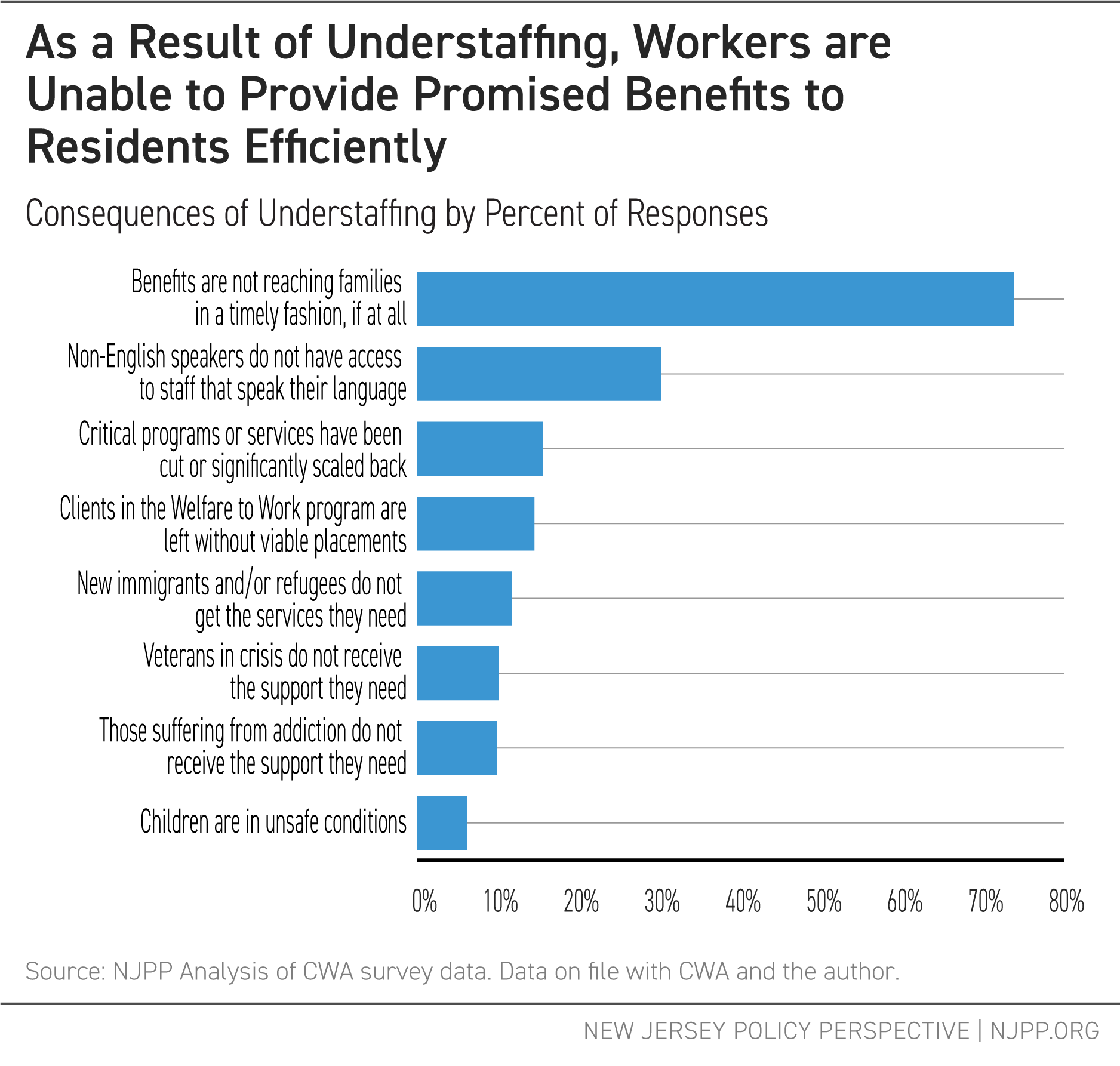

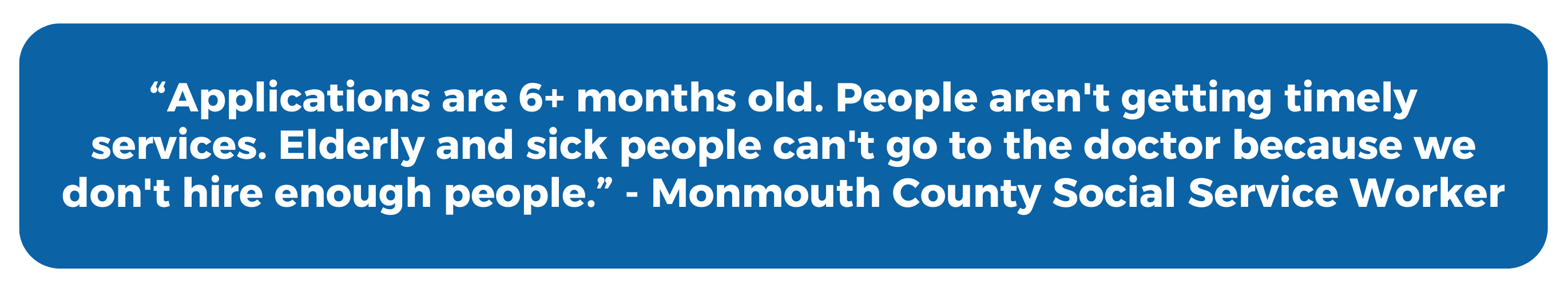

Nonetheless, one major obstacle to use of both programs is the uneven staffing levels and training at county social service agencies. County social service agencies are the main point of contact for applicants for programs such as SNAP or Work First New Jersey. As prior NJPP research has shown, low staffing levels at these agencies have led to higher caseloads, while low pay makes it difficult to retain staff.[40]

Application and paperwork challenges also remain for tax filing, which is required to obtain the Child and Earned Income Tax Credits. People and families who do not file state taxes end up missing out on critical payments, including people who live in poverty, who are Hispanic or Black, who are single parents, or who live in rural areas.[41] Even among people who do file, tax credit provision is not automatic, instead requiring additional work on the part of the tax filer to apply for the credit. As a result, nearly 1 in 5 New Jersey EITC-eligible households who filed federal taxes did not claim the credit.[42] A recent cut to the free federal tax filing program Direct File will make tax filing even more burdensome for low-income families.

Making the application process less difficult and more automatic will improve the effectiveness of the programs in getting money to households who need it most. It is perhaps unsurprising that people with the least money have the hardest time filling out government forms.[43]

Reducing red tape, combined with higher benefit amount, would ease life substantially for lower-income families trying to get by in New Jersey.

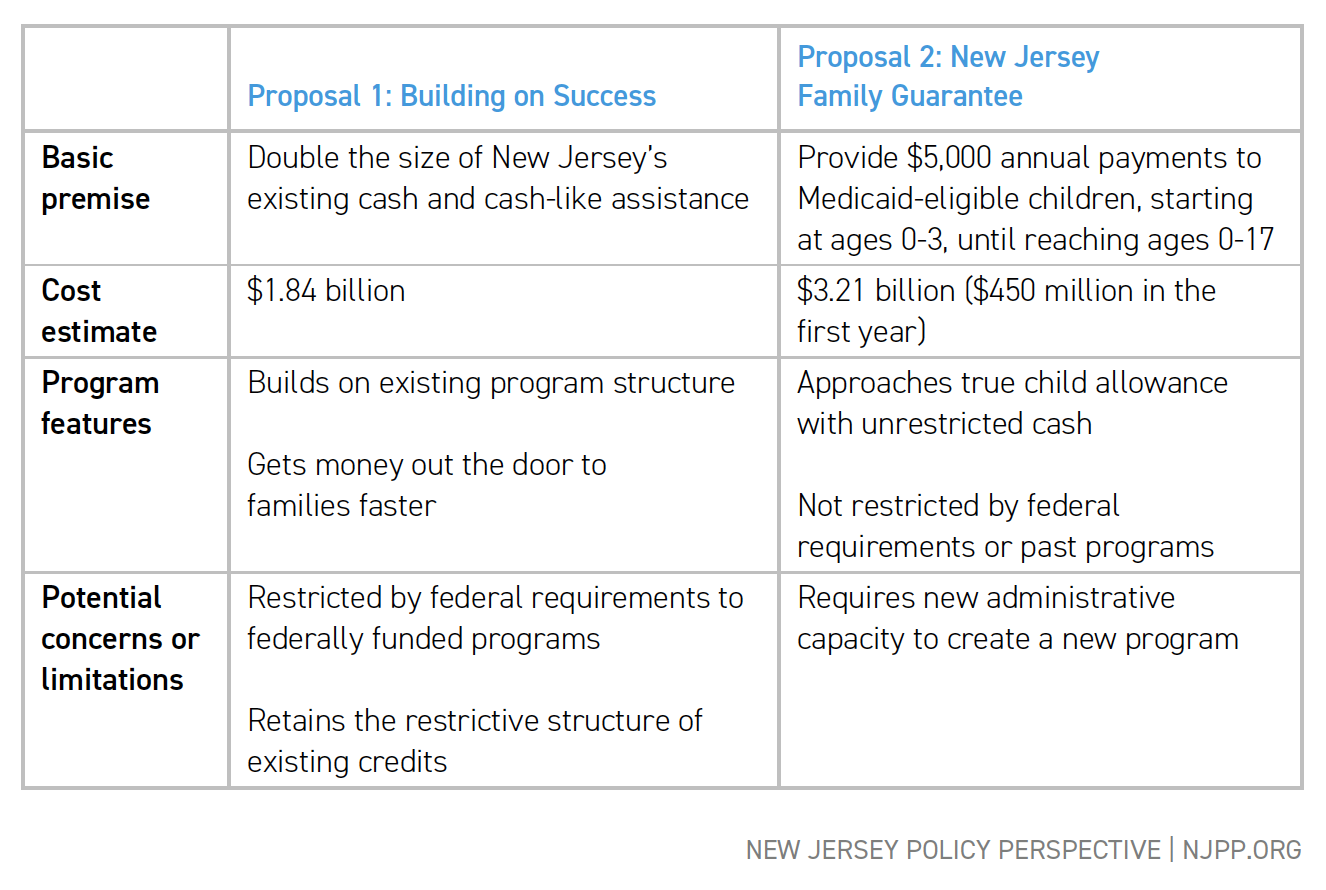

Pathway 2: The New Jersey Family Guarantee

The second pathway for New Jersey would be more life changing — to put the state on a path to provide a real child allowance and cut child poverty by half. Rather than simply expanding existing programs, this would set forth a new basic standard for all children in the state.

Put simply, the program would guarantee a $5,000 annual payment to all Medicaid-eligible children in New Jersey (roughly 150 percent of the federal poverty level) or whose births were covered by New Jersey’s Medicaid program for pregnant mothers (roughly 200 percent of the federal poverty level).[44] This would reach the more than 640,000 New Jersey children who receive Medicaid, roughly 1 in 3 children, including those eligible through the state-funded Cover All Kids program.[45]

The program would have a modest start, focused on a smaller age range (ages 0-3) and a lump-sum payment, laying the groundwork for a world where New Jersey children don’t face the economic chaos of deep poverty.

The $5,000 benefit amount is in line with prior efforts to determine the benefit needed to cut child poverty in half in New Jersey. In 2022, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimated a $4,400 Child Tax Credit would reduce poverty by 50 percent, which adjusted for inflation, would now be worth more than $4,760.[46] The $3,600 expanded Child Tax Credit from 2021, which dramatically slashed child poverty nationally, would also be worth more than $4,250 in 2025 dollars.[47]

The program would start with a focus on the first three years of life — enrolling families during pregnancy and making them eligible for the $5,000 annual payment as a tax credit, building on the Child Tax Credit. This shares some similarities with the Rx Kids program in Michigan, which uses state TANF funds to provide a lump sum payment and subsequent monthly $500 payments to pregnant and new mothers.[48]

The program would also likely need a phase-out at higher income levels to avoid a “cliff effect,” when a raise in salary or income makes a family ineligible for benefits, leaving them with fewer resources despite gaining income.[49] For the purposes of this cost estimate, however, no phase-out was modeled to make the estimate as conservative as possible.

With each following year of the New Jersey Family Guarantee rollout, an additional year of life would be added to the eligibility range. This gradual increase would help control the cost and allow relevant departments to iron out challenges and address management concerns early on. Eligibility based on Medicaid-covered births would last through age 6, after which benefits would only go out if the child remained Medicaid-eligible.

Such a program would require government staff and systems to stand up. The program would require coordination between the state’s Department of Human Services, which runs the Medicaid program, and the Department of the Treasury, which administers the tax code. To make the process as seamless as possible, the departments would need to create new rules and agreements to protect people’s privacy when sharing information between agencies.

But at its core, the New Jersey Family Guarantee provides a framework for the state to stand as a leader in poverty reduction. No child born in New Jersey would need to go hungry or without the most basic needs if this proposal were fully funded.

Comparing the Proposals

The ramp-up to Path 1 would be substantially faster, with preexisting programs that can simply be increased in size. Path 2 would require more lead time to ensure seamless delivery of the benefit while limiting the administrative burden for applicants and state departments. Importantly, the New Jersey Family Guarantee would be free of federal application and eligibility restrictions that affect the Earned Income Tax Credit, Work First New Jersey, and SNAP, such as work or citizenship requirements.

Both programs also leave open the possibility of shifting to periodic payments more in line with monthly child allowances and guaranteed income pilots. Depending on whether a payment is received as a lump sum or monthly payment, families often change their spending behavior to reflect larger costs like car repairs or smaller recurring ones like groceries.[50] However, at the moment, recurring payments rather than lump-sum tax credit payments often trigger eligibility rules for other safety net programs such as Medicaid or housing assistance.[51]

As to the question of cost, these proposals are necessarily substantial investments. In order for these programs to make a real dent in poverty and hardship affecting as much as one-third to one-half of residents, the state must commit resources.

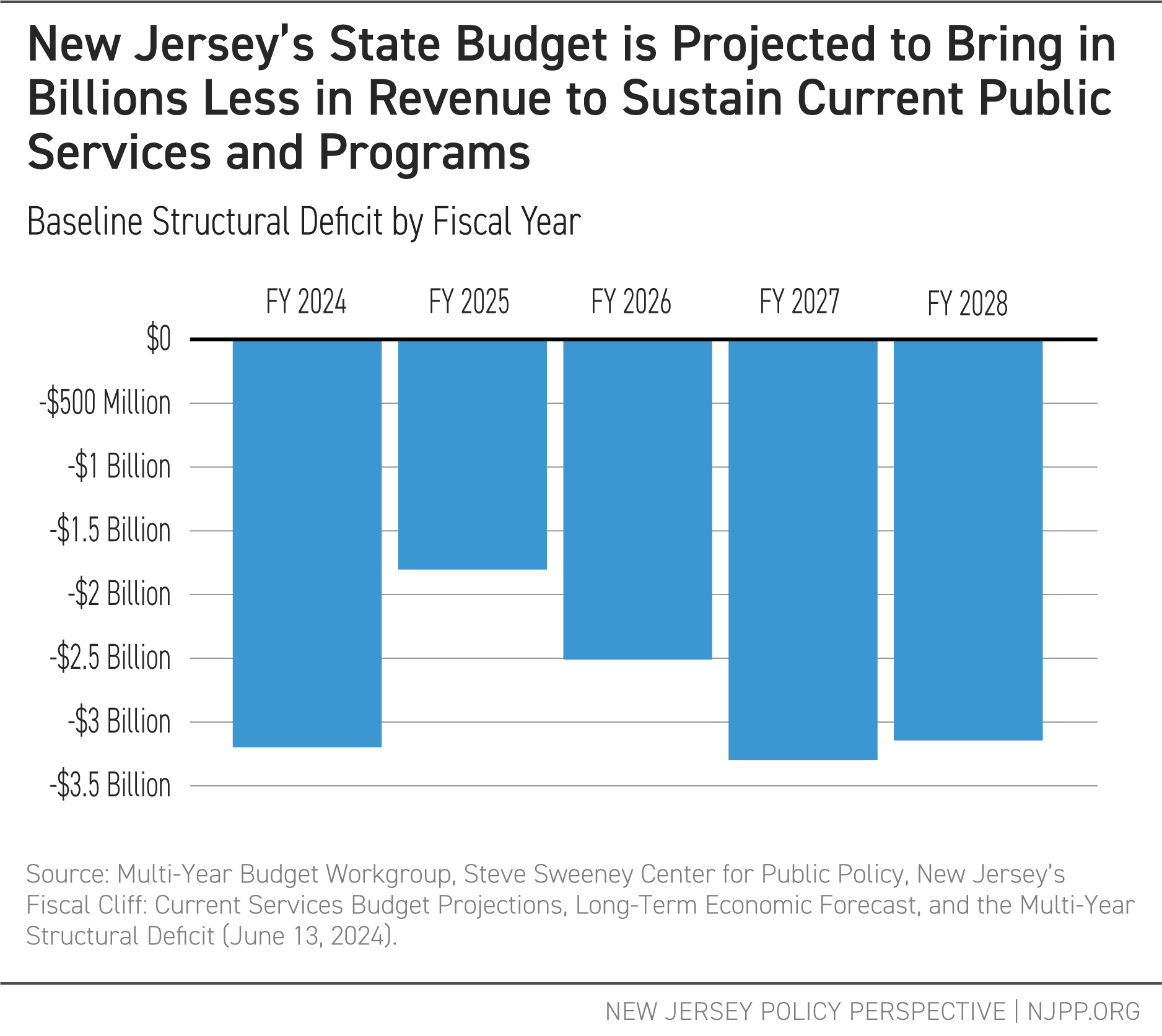

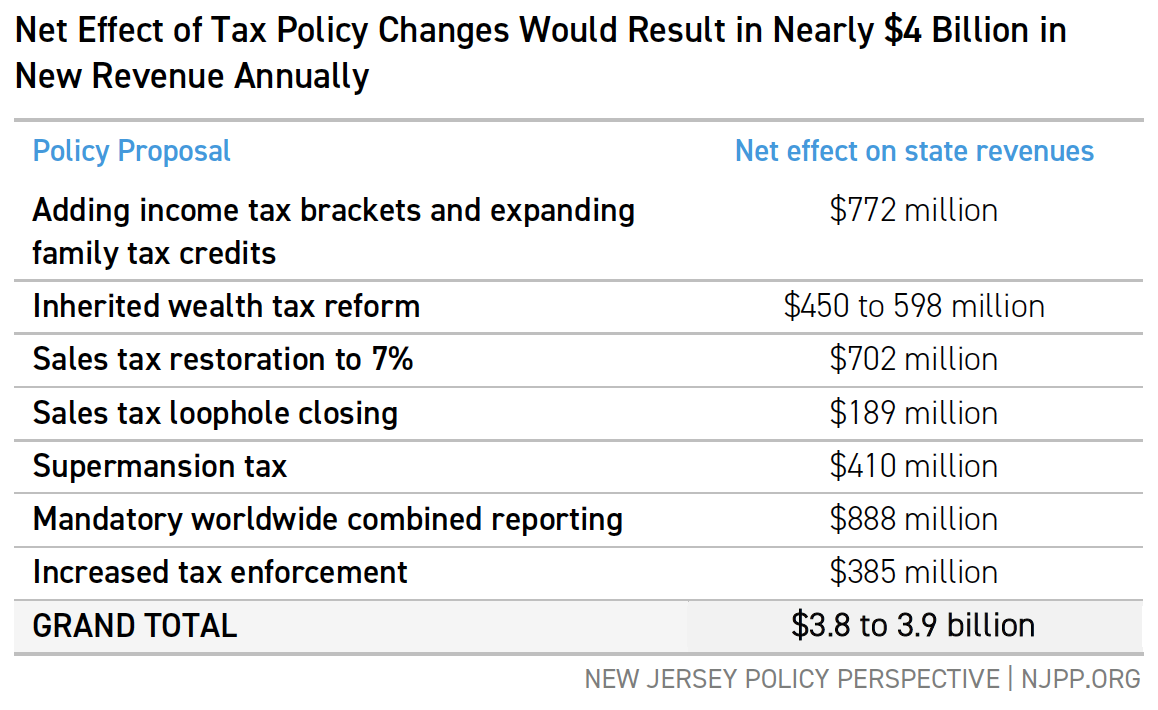

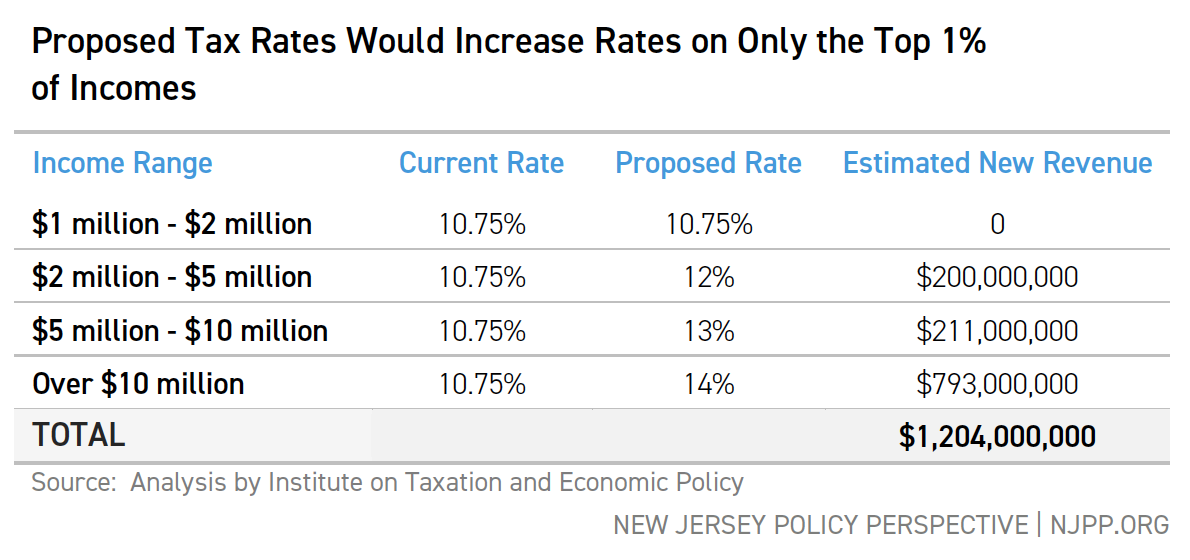

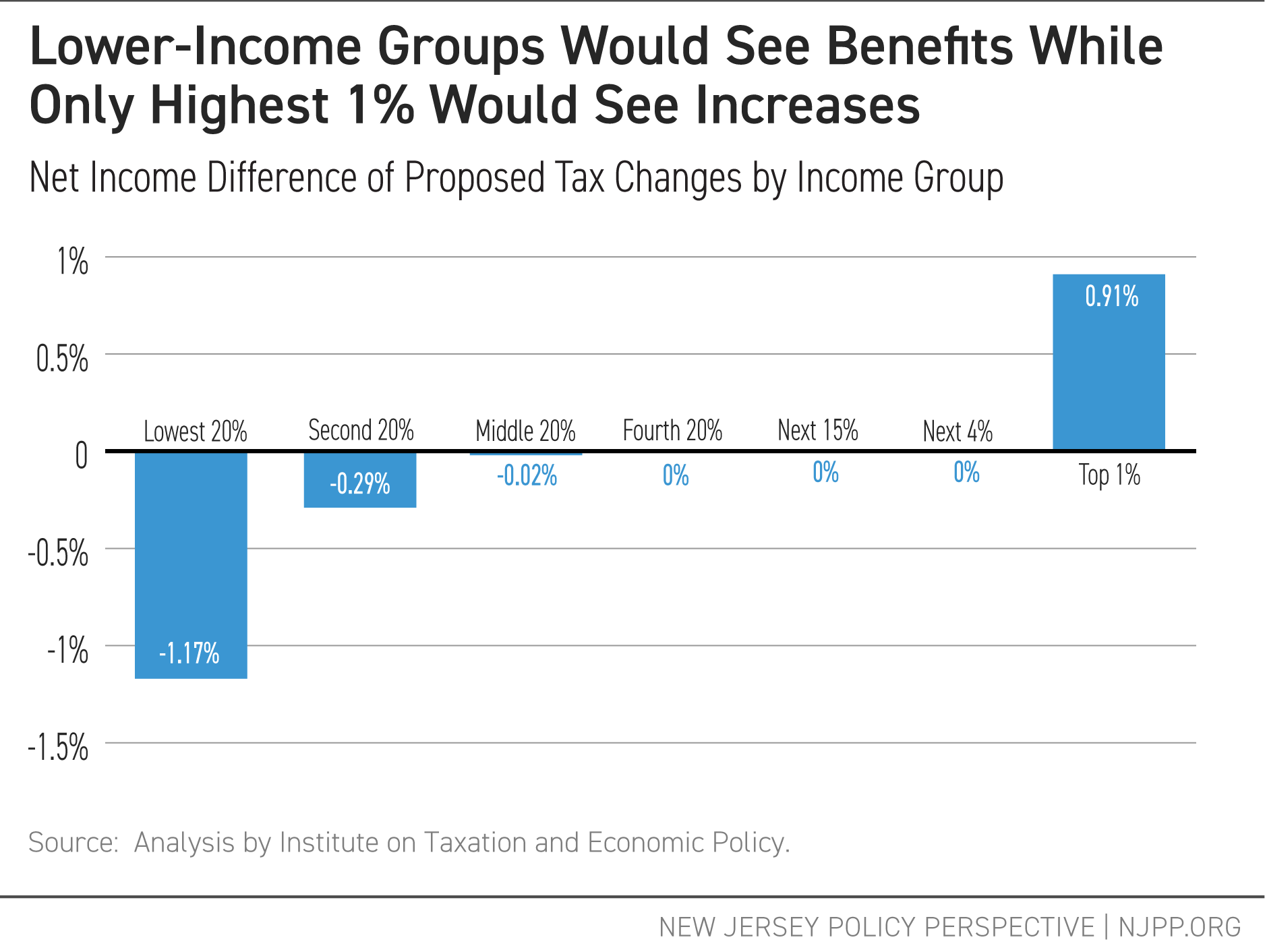

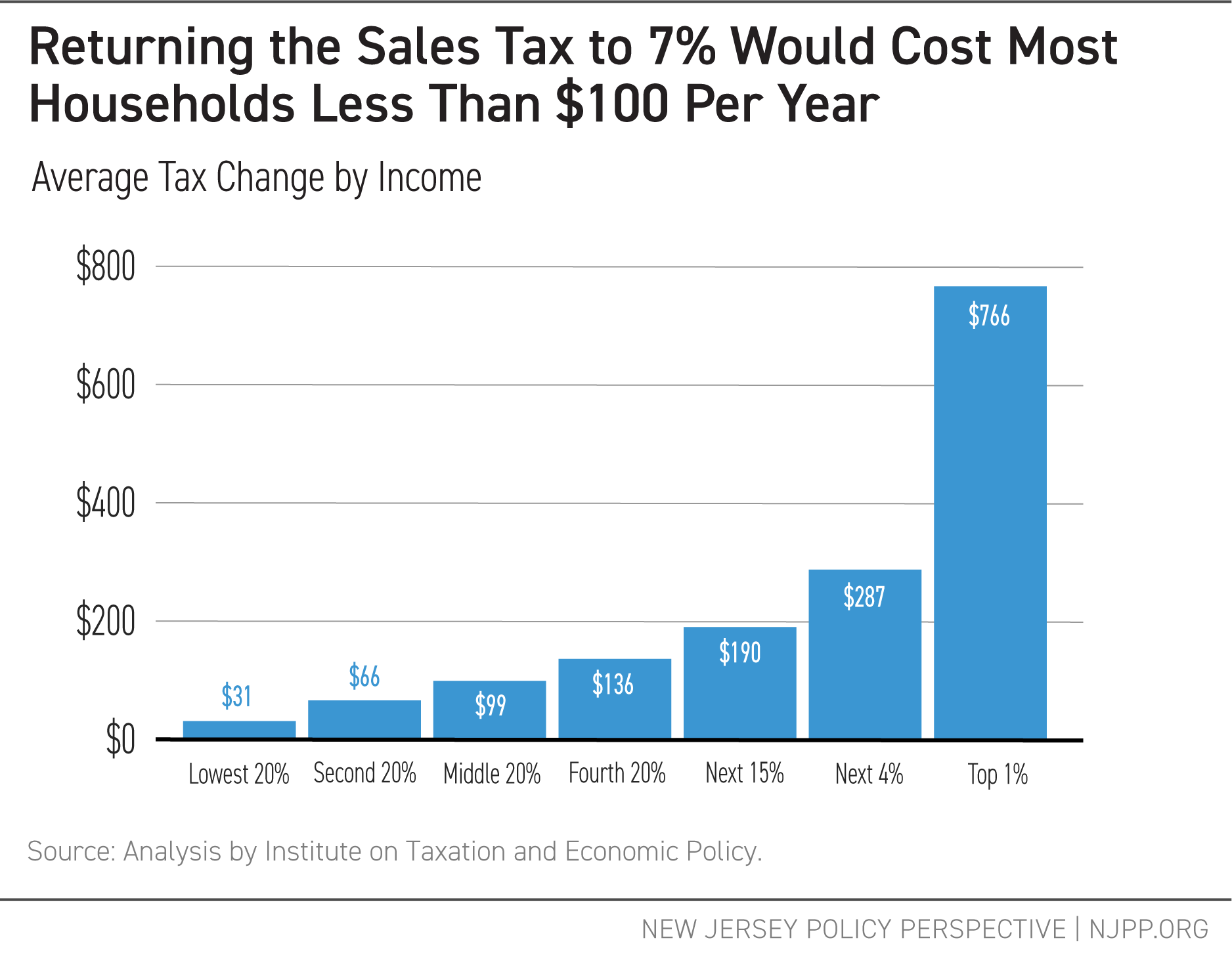

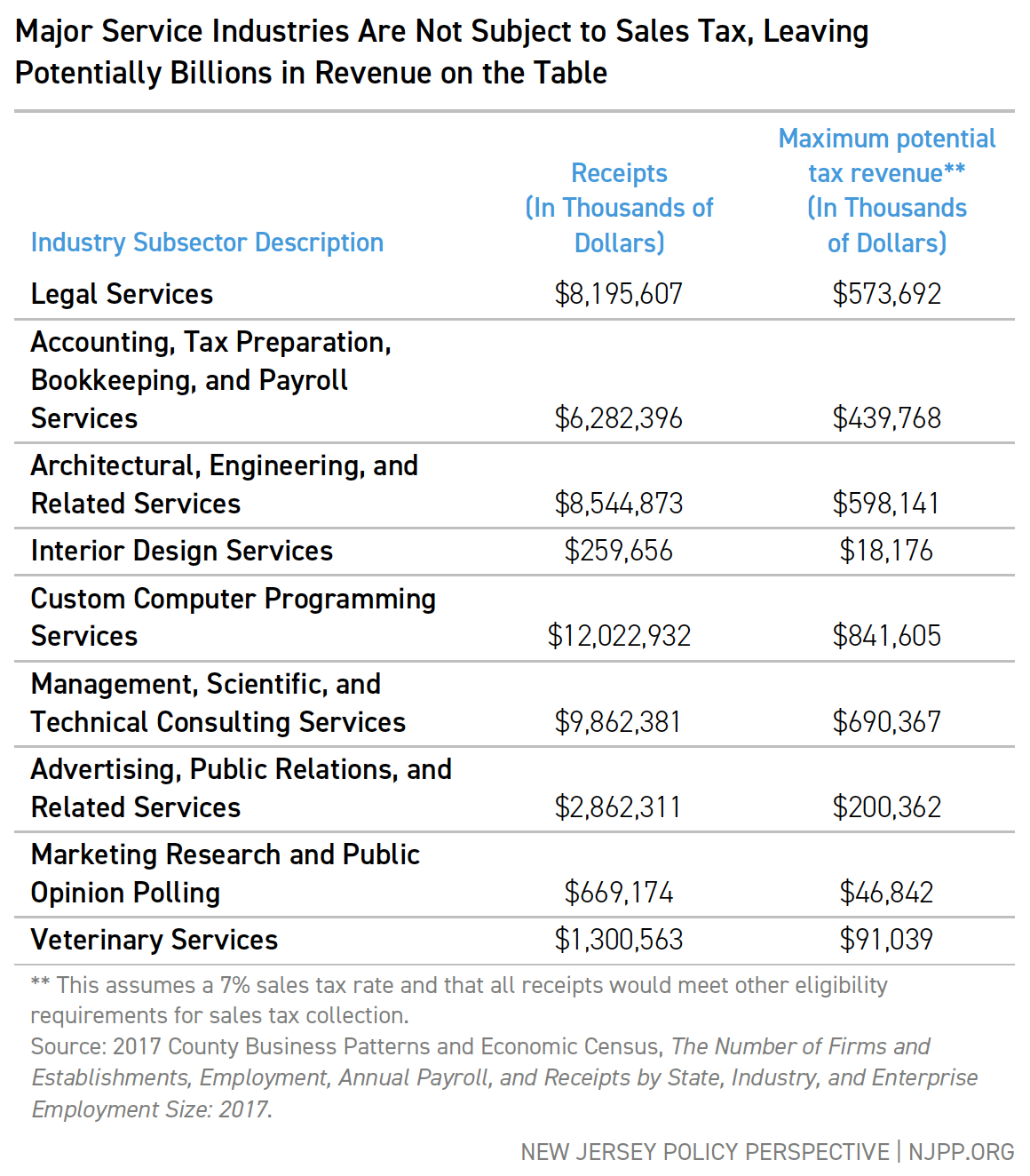

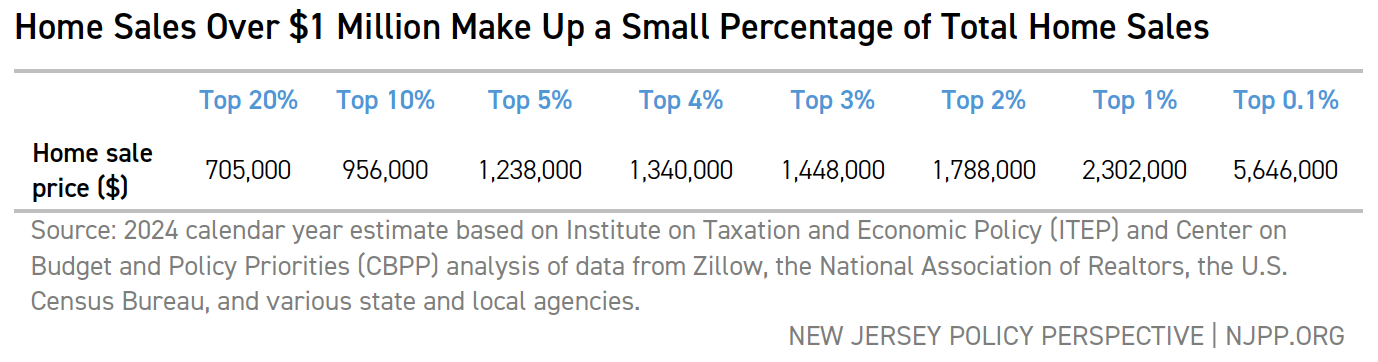

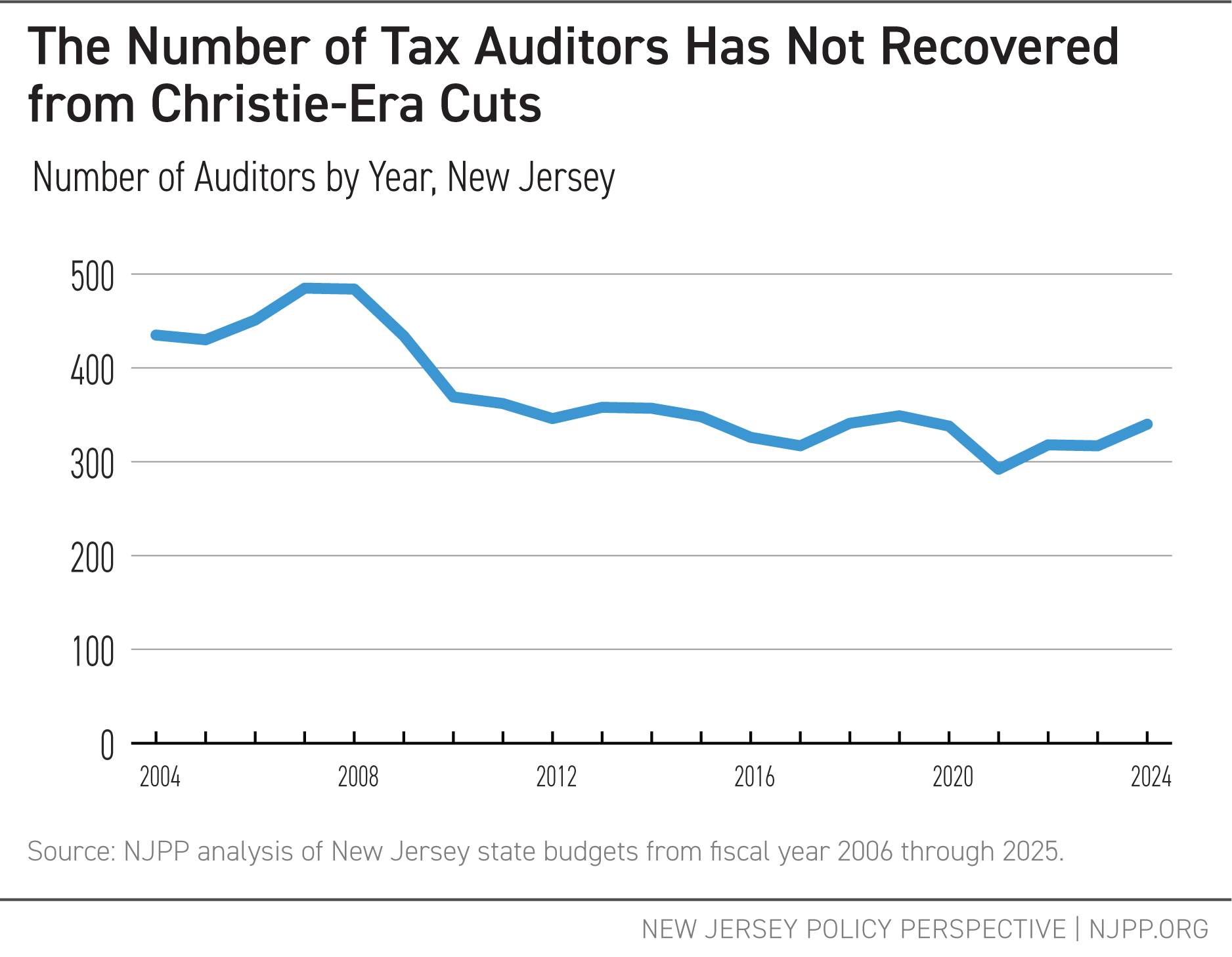

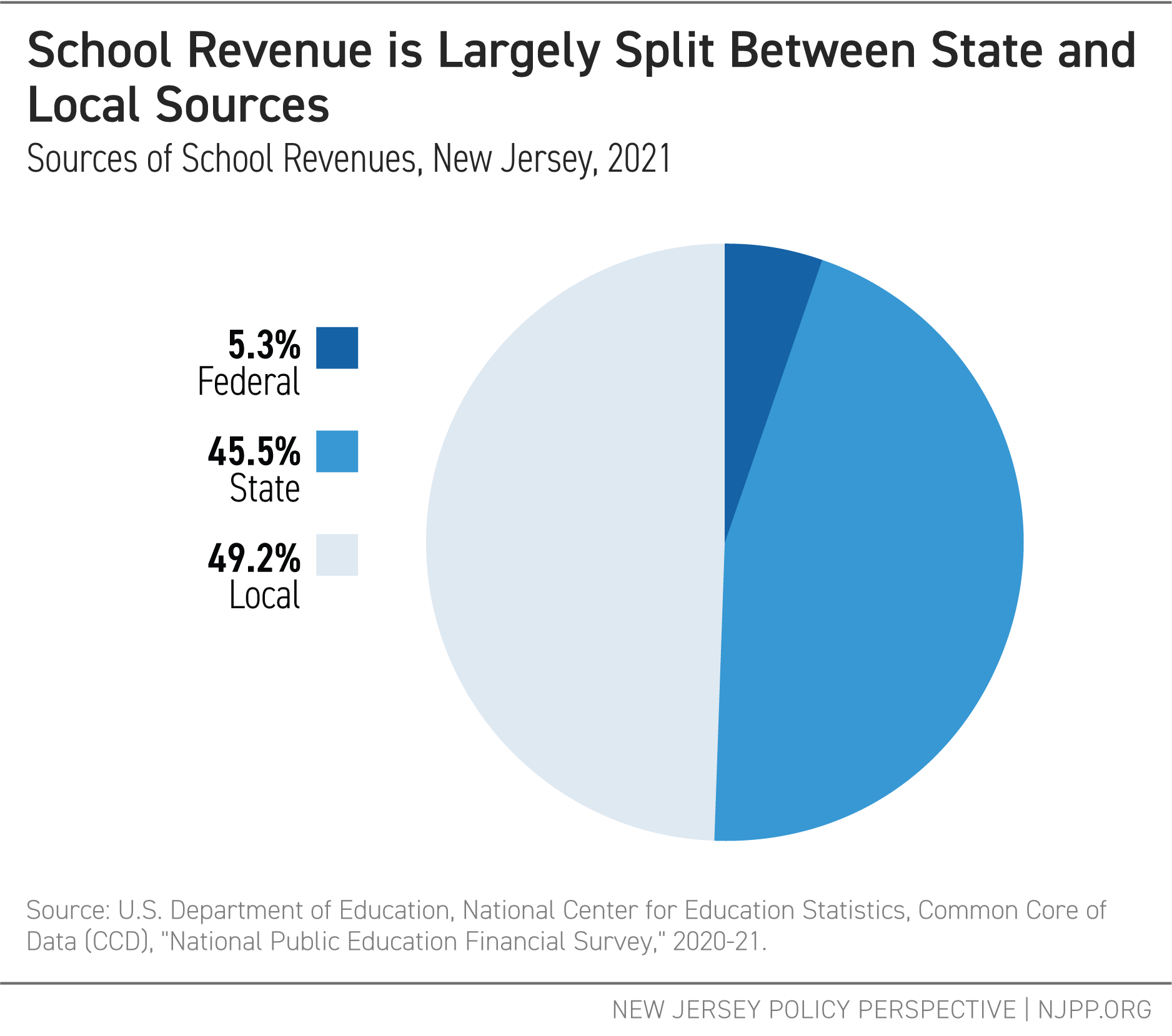

NJPP has previously proposed a list of revenue-raising policy changes that would generate sufficient revenue primarily from wealthy individuals and corporations to fund the larger of the two proposals.[52]

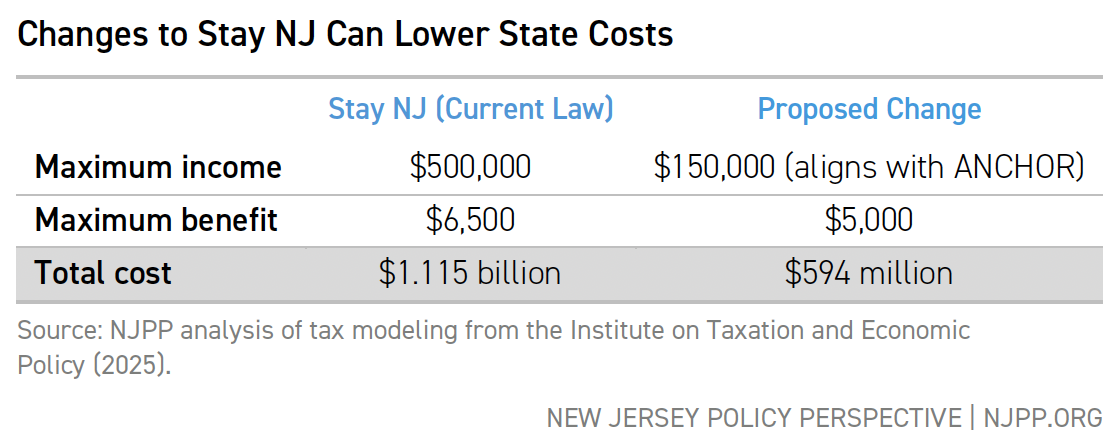

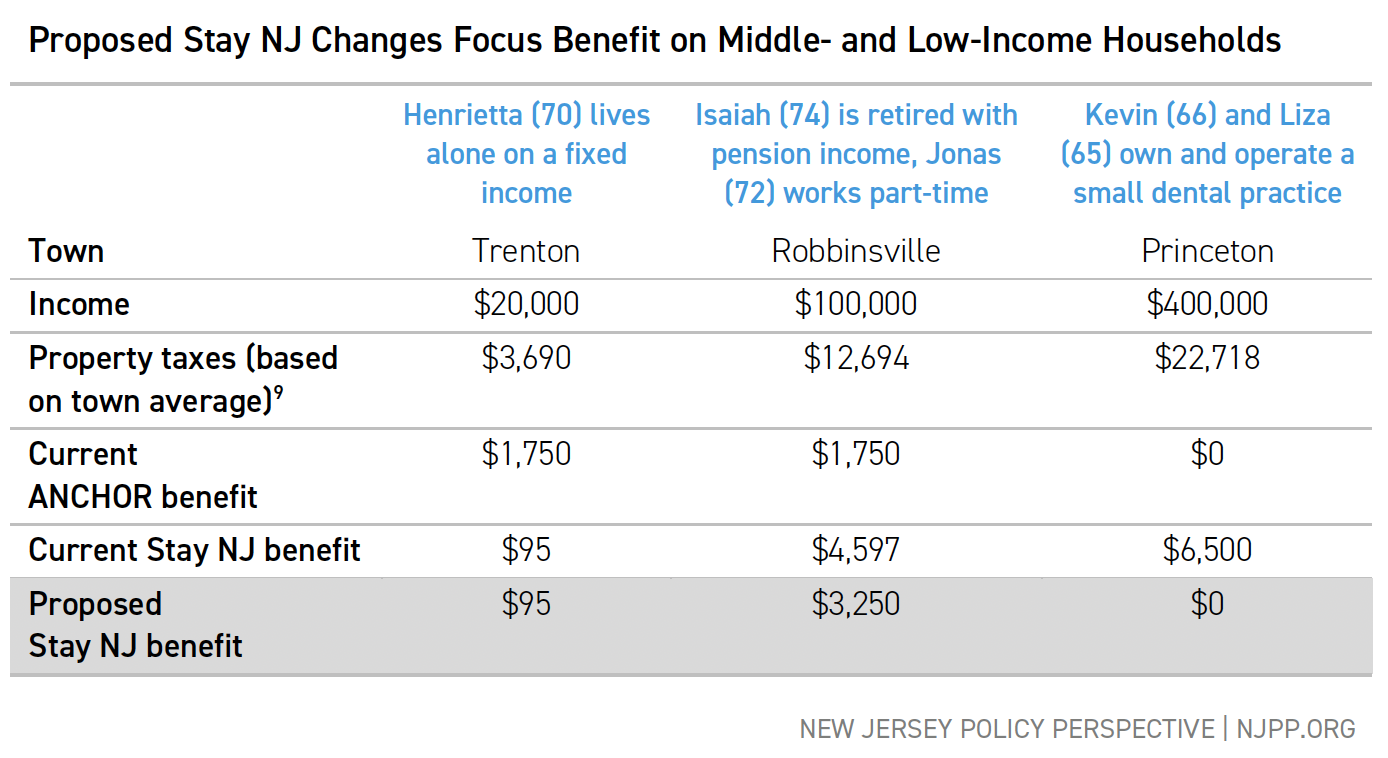

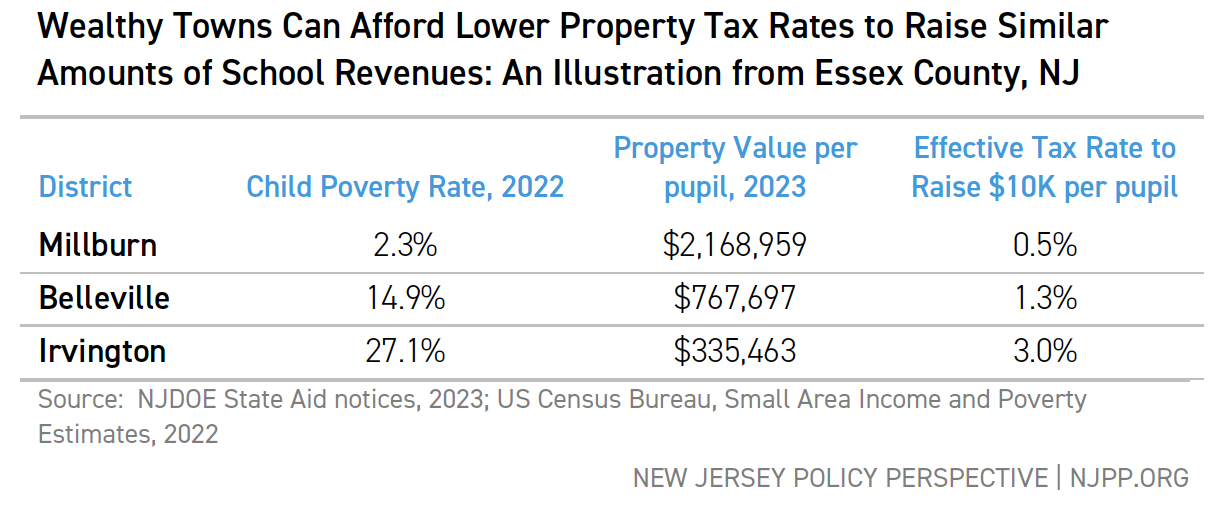

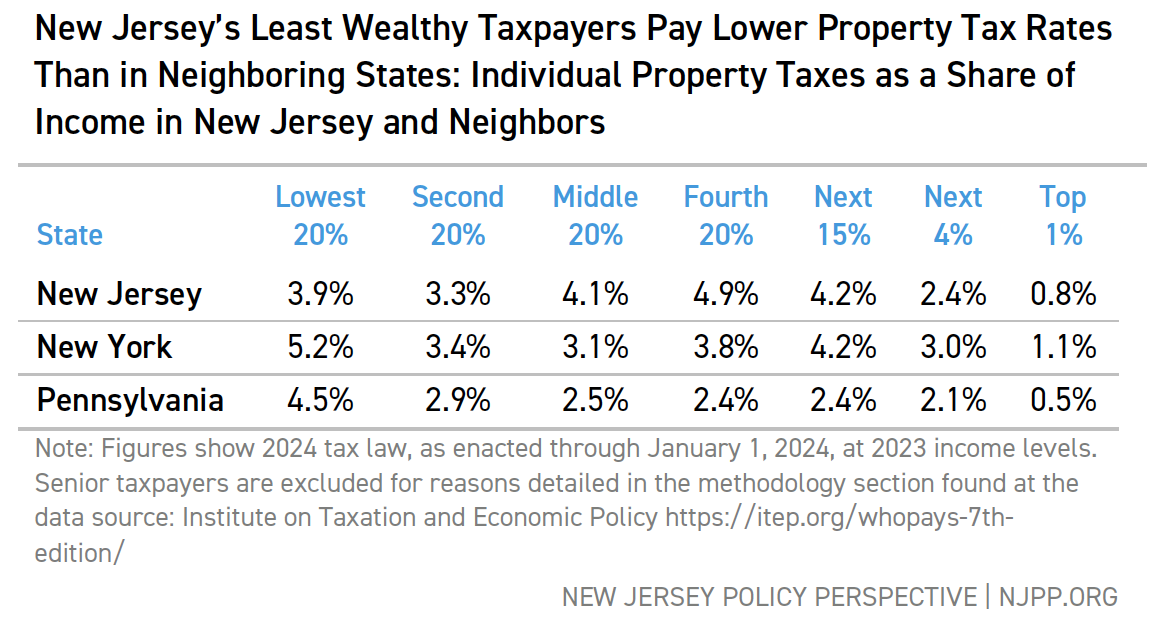

Although the price tags of $1.84 to $3.21 billion may seem high, state policymakers have seen fit in the past five years to send cash through tax credits for other kinds of recipients:

- $4.88 billion in annual property tax credits, including $1.2 billion in Stay NJ credits and $2.43 billion in ANCHOR credits[53]

- $249 million annually on film and digital media tax credits[54]

- $500 million in artificial intelligence business tax credits[55]

Economic analysis has shown that for every $1 invested in a universal child allowance, society would see $10 in benefits in the long run due to higher future earnings, improved health, and reduced costs.[56] New Jersey’s investment in child poverty reduction would pay substantial dividends for residents now and in the future.

For policymakers looking to make New Jersey truly affordable for families trying to raise children in the state, both proposals offer pathways towards economic security and simply having enough to thrive.

Conclusion

From the Old Age Relief Act of 1931[57] to today’s modern tax credits, New Jersey has long led the nation in fighting poverty. We can lead again.

The federal government has abandoned working families.[58] As politicians and policymakers voice concerns about the affordability of raising a family in New Jersey,[59] these proposals offer a real solution — putting cash directly in families’ pockets to cover high living costs and help hundreds of thousands of children get healthy food, safe housing, and other basic needs.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said in 1967, “[t]he curse of poverty has no justification in our age.”[60] The sentiment was as true then as it is now. Wealth has only continued to grow while poverty remains stubbornly high.[61] In one of America’s wealthiest states, these plans could end the curse of child poverty, if policymakers are willing to make families a priority.

New Jersey Policy Perspective acknowledges the contributions of NJPP’s Crotty Fellow Kimberly Thomson, who researched and analyzed basic income proposals to model potential scenarios for New Jersey in 2021. New Jersey Policy Perspective also thanks the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities for their feedback and partnership in writing this report, as well as the Economic Security Project for its extensive background information on guaranteed income pilots and policy changes across the country.

End Notes

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. “Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months.” American Community Survey, ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1701, https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S1701?q=child+poverty&g=040XX00US34. Accessed on 29 Jul 2025; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2025 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (all states except Alaska and Hawaii) (2024),

https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/dd73d4f00d8a819d10b2fdb70d254f7b/detailed-guidelines-2025.pdf.

[2] Roosevelt, F. Annual Message (Four Freedoms) to Congress, Jan. 1941, available at https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/president-franklin-roosevelts-annual-message-to-congress.

[3] United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, art. 25, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[4] Koebel, K. and Stabile, M., Child Benefits in an International Comparative Context, VoxEU.org, Jul. 17, 2024, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/child-benefits-international-comparative-context

[5] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, By the Numbers: Harmful Republican Megabill Favors the Wealthy and Leaves Millions of Working Families Behind. Aug. 1, 2025. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/6-18-25health-policybrief.pdf

[6] Engel, K. and Posey, K., Household Income in States and Metropolitan Areas: 2023, U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey Briefs, ACSBR-023, Sept. 2024. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2024/demo/acsbr-023.pdf

[7] Compare U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Gross Domestic Product: All Industry Total in New Jersey [NJNGSP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NJNGSP, July 29, 2025 with World Bank Group, GDP (current US$), https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?most_recent_value_desc=true, July 29, 2025.

[8] Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. Evidence Review: State Earned Income Tax Credit, Oct. 2024, https://pn3policy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/PN3PIC_StateEITC_EvidenceReview_1024.pdf; Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. State Child Tax Credits: A Promising Policy To Improve Child Outcomes (2025). https://pn3policy.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/CTC-brief-3-31-25.pdf

[9] DeYoung, E., Castro, A., Tandon, N., & West, S., Guaranteed Income and Reconstructing Home: Housing, Parenting, and Educational Outcomes in Newark, New Jersey, University of Pennsylvania, Center for Guaranteed Income Research, Jun. 2025, https://upenn.app.box.com/v/CGIR-Report-Newark-NJ-2.

[10] Murphy, P., The State of New Jersey Budget in Brief, Summary of Budget Recommendations Fiscal Year 2026, Feb. 2025, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/26bib/BIB.pdf at 12. The $4.88 billion figure reflects the $4.28 billion budgeted for fiscal year 2026, along with another $600 million for a full year’s Stay NJ payment, as the fiscal year 2026 payment only reflects two quarters of payments.

[11] Duncan GJ, Ziol-Guest KM, Kalil A. Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Dev. 2010 Jan-Feb;81(1):306-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20331669/

[12] Schmidt, K. et al., Society to cell: How child poverty gets “Under the Skin” to influence child development and lifelong health, Developmental Review vol. 61, Sep. 2021, 100983, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0273229721000381

[13] Annie E. Casey Kids Count Data Center. Children in Poverty by Race and Ethnicity in United States: New Jersey. Sept. 2024. https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/44-children-in-poverty-by-race-and-ethnicity?loc=1&loct=2#detailed/2/32/false/2545,1095,2048,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36/187,11,9,12,1,185,13/324,323

[14] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/25246. P. 4

[15] Legal Services of New Jersey Policy Research Institute, True Poverty: What It Takes to Avoid Poverty and Deprivation in the Garden State. Jul. 2021. https://proxy.lsnj.org/rcenter/GetPublicDocument/00b5ccde-9b51-48de-abe3-55dd767a685a

[16] Economic Policy Institute. Family Budget Calculator. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/ (based on Middlesex County, NJ).

[17] Burns, K., Fox, L., and Wilson, D. Expansions to Child Tax Credit Contributed to 46% Decline in Child Poverty Since 2020. U.S. Census Bureau. Sep. 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/record-drop-in-child-poverty.html.

[18] Burns, K., Wilson, D., and Fox, L. Two Rounds of Stimulus Payments Lifted 11.7 Million People Out of Poverty During the Pandemic in 2020. U.S. Census Bureau. Sept. 14, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/09/who-was-lifted-out-of-poverty-by-stimulus-payments.html

[19] DeYoung, E., Castro, A., Tandon, N., & West, S., Guaranteed Income and Reconstructing Home: Housing, Parenting, and Educational Outcomes in Newark, New Jersey, University of Pennsylvania, Center for Guaranteed Income Research, Jun. 2025, https://upenn.app.box.com/v/CGIR-Report-Newark-NJ-2. DeYoung, E., Tandon, N., Neves, C., Castro, A., & West, S. (2023, December). The American Guaranteed Income Studies: Paterson, New Jersey. University of Pennsylvania Center for Guaranteed Income Research. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5fdc101bc3cfda2dcf0a2244/t/664dea70834dfc74bc8643b6/1716382324073/CGIR%2BFinal%2BReport_Paterson%2BNJ_12.2023.pdf

[20] Akee, R. et al., Parents’ Incomes and Children’s Outcomes: A Quasi-experiment Using Transfer Payments from Casino Profits. American Econ. Journal: Applied Economics 2(1). Jan. 2010. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.2.1.86; Bruckner, T.A., Bustos, B., Dodge, K.A. et al. Intergenerational effects of a casino-funded family transfer program on educational outcomes in an American Indian community. Nat Commun 15, 8168 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52428-w.

[21] Burnside, A., The SNAP Hot Foods Ban Is Inequitable and Should Be Removed. Center for Law and Social Policy. May 2023. https://www.clasp.org/blog/the-snap-hot-foods-ban-is-inequitable-and-should-be-removed/.

[22] Floyd, I., et al. TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Aug. 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance

[23] Tandon, N., West, S., DeYoung, E., Patel, H., Thompson, A., & Castro, A. (2025, June). The

American Guaranteed Income Studies: Newark, New Jersey, Lump-Sum vs. Recurring Cash

Transfers. University of Pennsylvania, Center for Guaranteed Income, https://upenn.app.box.com/v/CGIR-Report-Newark-NJ.

[24] Landry, J. Guaranteed Income In The Wild: Summarizing Evidence From Pilot Studies and

Implications for Policy. Jain Family Institute. Dec. 2024. https://jainfamilyinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Guaranteed-Income-Pilot-Report-Jack-Landry-12.9.24.pdf pp. 16-17.

[25] Landry, J. Guaranteed Income In The Wild: Summarizing Evidence From Pilot Studies and

Implications for Policy. Jain Family Institute. Dec. 2024. https://jainfamilyinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Guaranteed-Income-Pilot-Report-Jack-Landry-12.9.24.pdf pp. 12-14.

[26] New Jersey Treasury. Who Must File. May 2025. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/njit23.shtml

[27] Bergh, K., Nchako, C. and Nuñez, L. Worsening SNAP’s Harsh Work Requirement Would Take Food Assistance Away From Millions of Low-Income People. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Apr. 2025. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/worsening-snaps-harsh-work-requirement-would-take-food-assistance-away; LaCarte, V., Hinkle, L., and Broberg, B. SNAP Access and Participation in

U.S.-Born and Immigrant Households: A Data Profile. Migration Policy Institute. Mar. 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/snap-us-immigrant-households. Castro, R. Promoting Equal Opportunities for Children Living in Poverty. New Jersey Policy Perspective. Apr. 2020. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/promoting-equal-opportunities-for-children-living-in-poverty/.

[28] Schweitzer, J. How To Address the Administrative Burdens of Accessing the Safety Net. Center for American Progress. May 2022. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-to-address-the-administrative-burdens-of-accessing-the-safety-net/.

[29] New Jersey Department of Human Services. Work First New Jersey: Using Your Benefits. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/wfnj/recipients/benefits/

[30] Tax Policy Center. Briefing Book: How does the earned income tax credit affect poor families? Jan. 2024. https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/how-does-earned-income-tax-credit-affect-poor-families

[31] New Jersey State Health Assessment Data. Poverty among Children Under Five Years of Age by Race/Ethnicity, New Jersey, 2019-2023. Dec. 2024. https://www-doh.nj.gov/doh-shad/indicator/view/EPHT_LT5_pov.RE.html

[32] Hardy, B., & Hokayem, C. (2024). The Effects of the 2021 Child Tax Credit on Racial and Ethnic Inequalities in Well-Being. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 710(1), 157-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162241265791 (Original work published 2023).

[33] New Jersey Reparations Council. For Such A Time As This: The Nowness of Reparations for Black People in New Jersey. Jun. 2025. https://www.njisj.org/print/njrcreport.pdf. Pp. 170-172.

[34] Lee, J., et al., Effects of the Expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit for Childless Young Adults on Material Wellbeing. NBER Working Paper No. 32571. Jun. 2024. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32571

[35] Murphy, P. The State of New Jersey Budget in Brief, Summary of Budget Recommendations Fiscal Year 2026. Feb. 2025. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/26bib/BIB.pdf pp. 25-26.

[36] Moynihan D., Herd, P., Harvey, H. Administrative Burden: Learning, Psychological, and Compliance Costs of Citizen-State Interactions. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Volume 25, Issue 1, January 2015, Pages 43-69, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu009. p. 51.

[37] Pub. L. No. 119-21, Sec. 10108 (2025).

[38] Castro, R. Promoting Equal Opportunities for Children Living in Poverty. New Jersey Policy Perspective. Apr. 2020. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/promoting-equal-opportunities-for-children-living-in-poverty/

[39] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Program Development Division. State Operations Report 15th Edition. 2023. https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-15th-state-options-report-october23.pdf

[40] Holom-Trundy, B., Understaffed and Underfunded: Barriers to Effective Anti-Poverty Assistance. New Jersey Policy Perspective and Communication Workers of America. Nov. 2024. https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/NJPP-CWA_-Understaffed-and-Underfunded_-Barriers-to-Effective-Anti-Poverty-Assistance-2.pdf

[41] Nguyễn, N. Who Gets Credit? Understanding Family Barriers in Tax Credit Access. New America Foundation New Practice Lab. May 20, 2025. https://www.newamerica.org/new-practice-lab/blog/easier-tax-credits-improves-family-well-being/

[42] Internal Revenue Service. EITC Participation Rate By States: Tax Years 2014 Through 2022. Apr. 9, 2025. https://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/participation-rate-by-state/eitc-participation-rate-by-states

[43] Herd, Pamela, and Donald Moynihan. 2025. “Administrative Burdens in the Social Safety Net.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 39 (1): 129–50. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.20231394 at 133.

[44] New Jersey Department of Human Services. Medicaid Communication No. 25-03. Feb. 28, 2025. https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dmahs/info/resources/medicaid/2025/25-03%20Income%20Eligibility%20Standards%20Effective%20January%201,%202025.pdf

[45] New Jersey Department of Human Services. New Jersey FamilyCare Monthly Enrollment Report. Jun. 2025. https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dmahs/news/reports/enrollment_2025_06.pdf p. 2. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid in New Jersey. May 2025. https://files.kff.org/attachment/fact-sheet-medicaid-state-NJ

[46] Davis, A. State Child Tax Credits and Child Poverty: A 50-State Analysis. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Nov. 16, 2022. https://itep.org/state-child-tax-credits-and-child-poverty-50-state-analysis/. Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Inflation Calculator. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=4400&year1=202211&year2=202506

[47] Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Inflation Calculator. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=3600&year1=202107&year2=202506

[48] Hanna, M. and Shaefer, L. Results from the Maternal Wellbeing Research Study. Rx Kids. https://rxkids.org/impact/research-brief/

[49] National Conference of State Legislatures. Introduction to Benefits Cliffs and Public Assistance Programs. Dec. 27, 2024. https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/introduction-to-benefits-cliffs-and-public-assistance-programs

[50] Parolin, Zachary, Elizabeth Ananat, Sophie Collyer, Megan Curran, and Christopher Wimer. 2023. The effects of the monthly and lump-sum Child Tax Credit Payments on food and housing hardship. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, vol. 113: 406-412. doi: 10.1257/pandp.20231088

[51] Economic Security Project & Shriver Center on Poverty Law. Guaranteed Income: States Lead the Way in Reimagining the Social Safety Net. April 2022. https://economicsecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/States_Lead_the_Way.pdf

[52] Chen, P. Fair and Square: Changing New Jersey’s Tax Code to Promote Equity and Fiscal Responsibility. New Jersey Policy Perspective. Nov. 14, 2024. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/fair-and-square-changing-new-jerseys-tax-code-to-promote-equity-and-fiscal-responsibility/

[53] Murphy, P., The State of New Jersey Budget in Brief, Summary of Budget Recommendations Fiscal Year 2026, Feb. 2025, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/26bib/BIB.pdf at 12.

[54] State of New Jersey. Tax Expenditure Report Fiscal Year 2026. 2025. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/pdf/taxexpenditurereport2025.pdf, p. 10.

[55] New Jersey P.L. 2024, c. 49. https://pub.njleg.gov/Bills/2024/PL24/49_.HTM

[56] Ananat, E., and Garfinkel, I. The Potential Long-Run Implications of a Permanently-Expanded Child Tax Credit. NBER Working Paper No. 32870. Aug. 2024. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32870.

[57] New Jersey Laws of 1931, c. 219. Text available at https://njlaw.rutgers.edu/cgi-bin/diglib.cgi?collect=njleg&file=155&page=0530&zoom=120

[58] Hanauer, A. GOP Megabill Breaks America’s Promise to Future Generations. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Jul. 10, 2025. https://itep.org/gop-megabill-breaks-americas-promise-future-generations/

[59] Nikita Biryukov. Here’s how the Democrats running to be governor say they’ll make New Jersey more affordable. New Jersey Monitor. May 29, 2025. https://newjerseymonitor.com/2025/05/29/heres-how-the-democrats-running-to-be-governor-say-theyll-make-new-jersey-more-affordable/; Economic Policy Institute. Family Budget Calculator. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/ (based on Middlesex County, NJ)

[60] King, M. Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? 1967. P. 175. https://archive.org/details/82818file/page/n3/mode/1up

[61] Columbia Population Research Center and Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University. New Jersey: Anchored SPM Poverty Trends 1967-2014. https://povertycenter.columbia.edu/sites/povertycenter.columbia.edu/files/content/Publications/Poverty%20in%20the%2050%20states/New-Jersey-Anchored-SPM-Trends.pdf

Right-Size the Income Tax: Raise Rates at the Top, Lower Them at the Bottom

Right-Size the Income Tax: Raise Rates at the Top, Lower Them at the Bottom

Local Fair Share

Local Fair Share