To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

Increasing New Jersey’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to 35 percent from 30 percent of the federal EITC will provide over half a million New Jersey working families with a much-needed bump in their take-home pay while giving the state’s economy a boost.

The state’s EITC supplements the federal EITC, an income tax credit for low-income working people that rewards work and boosts the pay of families across the country. Working families with qualifing children and earned incomes up to $53,505 (for married couples filing jointly and with three or more children in tax year 2016) are eligible for this tax credit; adults without children with earned incomes less than $14,880 are also eligible.

Working New Jerseyans are currently eligible to receive 30 percent of the federal credit received through the state EITC, which was created in 2000, rose to 25 percent in 2009, was cut to 20 percent in 2010 and was increased to 30 percent last year.[1] In 2013, the latest year for which state data are available, 576,400 New Jersey households claimed the credit on their tax returns.[2] In 2014, according to federal data compiled by the Brookings Institution, 594,700 New Jersey households claimed the federal EITC.[3]

Increasing the EITC to 35 percent will help nearly 600,000 New Jersey families whose members are working but not earning enough to get by in this high-cost state. These workers’ annual take-home pay will increase by an average of $116 (and by as much as $314), bringing the average total of state EITC dollars received to $811 a year.[4]

This income boost will be crucial for these working families in tandem with the fuel tax increases simultaneously approved by the legislature to invest in critical road, bridge and transit infrastructure. After all, low-income and middle-class families will pay a larger share of their incomes to these new fuel taxes than other New Jerseyans – and a boost to the EITC helps mitigate that impact.[5]

However, the large-scale tax package that included the fuel tax and EITC increases also included more than $1.3 billion in additional annual tax cuts that will disproportionately help higher-income New Jersey families while crippling the state’s ability to maintain services that are essential to low-income working families.[6] So it’s by no means all good news for low-income working families.

That said, with a 35 percent EITC, New Jersey will be a national leader in boosting the incomes of working families – and rightly so, given how expensive basic necessities like housing are here.

The Garden State now trails only the District of Columbia, which has a 40 percent credit; Minnesota and California have different structures that also allow for credits of more than 40 percent (the former’s range goes up to 45 percent; the latter’s, 85 percent).[7]

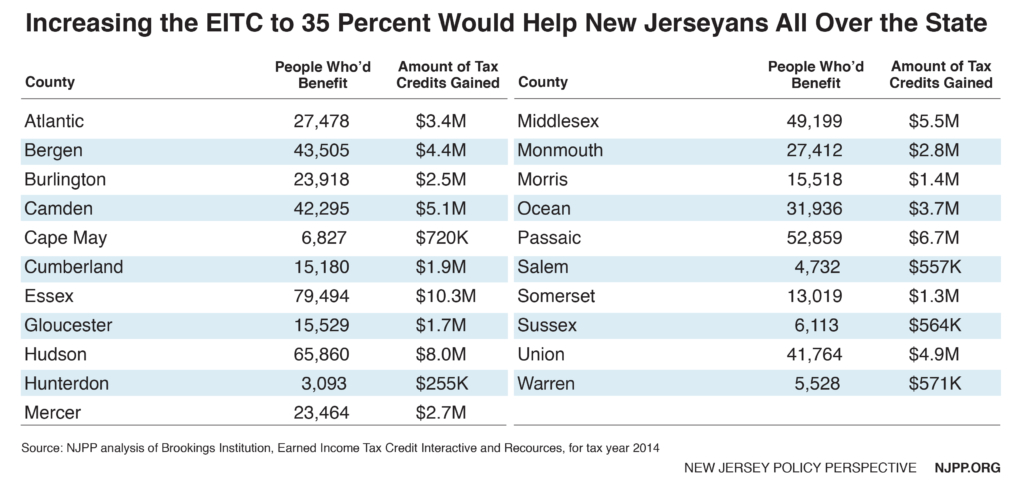

Families All Over New Jersey Will Benefit

Boosting the EITC will help working people all over New Jersey. All but five of the state’s 21 counties have more than 10,000 households receiving the EITC, and more than half of them (12) have over 20,000 EITC households.

Boosting the EITC will help working people all over New Jersey. All but five of the state’s 21 counties have more than 10,000 households receiving the EITC, and more than half of them (12) have over 20,000 EITC households.

The largest counties in each part of the state have tens of thousands of EITC households, with Essex County having the most recipients in North Jersey, Middlesex County having the most in Central Jersey and Camden County having the most in South Jersey.

While there are greater concentrations of EITC families in New Jersey’s urban centers, the use of this tax credit has spread to more suburban counties as families all over the state struggle with long-term unemployment and stagnant wages or fewer hours for those who have jobs. Even affluent counties like Morris and Somerset, for example, now have over 10,000 EITC families.

Increasing the EITC Will Help Poor Families the Most

Nine out of every ten New Jersey households that receive the EITC earn less than $30,000 a year. About three-quarters earn less than $20,000 and more than half – 61 percent – make less than $15,000.[8]

Nine out of every ten New Jersey households that receive the EITC earn less than $30,000 a year. About three-quarters earn less than $20,000 and more than half – 61 percent – make less than $15,000.[8]

These are families that are clearly struggling to get by in high-cost New Jersey. The EITC is critical to their struggles.

For example, the budet needed to meet basic needs in the least expensive metro area of the state (the Ocean City area) is $29,662 a year just for a single, childless adult. Add one child to the mix, and that nearly doubles, to $55,672 a year. And this is the most affordable part of the state. In the most expensive metro area (the Middlesex/Somerset/Hunterdon area), the budget needed for basic necessities is $67,026 a year for that same single parent.[9]

In other words, it’s clear that even this modest boost to the take-home pay of these families will allow them to better meet basic necessities like food and rent and rely less on the social safety net to survive.

Boosting the EITC Will Make Tax System More Equitable

Despite having a relatively progressive income tax based on one’s ability to pay, New Jersey’s tax system is still backwards, with the lowest-income households paying the highest share of their earnings to state and local taxes each year. This is due to the regressive nature of sales and property taxes. One of the best ways to help make this upside-down system more equitable is to increase the EITC.

Increasing New Jersey’s EITC to 35 percent will reduce the share of state and local taxes paid by the poorest families. While these New Jerseyans in the bottom 20 percent, whose average annual income is a scant $15,000, will still pay the largest share of their income to these taxes, the gap between this group and other New Jersey households would have been reduced if the EITC increase happened in a vacuum.[10]

But it didn’t. Instead, the EITC increase was paired with a broad-based fuel tax increase that will affect nearly every New Jerseyan, as well as a slew of tax cuts that will benefit wealthier families the most. In the end, each income group in New Jersey will pay a greater share of their incomes to state and local taxes after all of the changes from the Transportation Trust Fund deal.[11]

Expanding This Tax Credit Will Boost New Jersey’s Economy

The EITC is also a big-time economic stimulus for local economies. The New Jersey EITC distributes nearly $400 million in tax credits each year throughout the state,[12] while the federal EITC puts nearly $1.4 billion a year into the pockets of working New Jerseyans.[13]

The EITC is also a big-time economic stimulus for local economies. The New Jersey EITC distributes nearly $400 million in tax credits each year throughout the state,[12] while the federal EITC puts nearly $1.4 billion a year into the pockets of working New Jerseyans.[13]

But the economic impact of the EITC goes beyond the specific amount credited to each family. Low-wage workers tend to spend these tax credits immediately and locally on short- to medium-term needs like clothes for their family, repairs to the family car, household items or catching up on past-due rent or utility bills.[14]

Increasing the state EITC to 35 percent will further boost the tax credit’s economic impact, generating $69 million in new tax credits each year that will help boost local economies around the state, bringing millions of dollars of spending to almost every county.[15]

The EITC Promotes Work, Raises Living Standards and Helps Lift Families Out of Poverty

The EITC, traditionally a strongly bipartisan measure, is perhaps the most powerful anti-poverty tool available, with significantly positive effects on families who receive it.

The tax credit promotes work, particularly in strong labor markets. During the 1990s, for example, EITC expansions did more to raise employment among single mothers with children than either the changes to welfare during that time or the strong economy.[16]

Lifting a low-income family’s income when a child is young, as the EITC does, improves that child’s immediate well-being, as the family is able to better meet basic needs. But these income boosts have also been tied to better health and more schooling for these children, as well as more hours worked and higher earnings once they become adults.[17]

The extra dollars that these low-wage workers and their families receive each year keeps more than 150,000 New Jerseyans above the federal poverty level each year, including 79,000 New Jersey children.[18] Investing in a program that does so much to help low-income families across New Jersey is common sense.

Next Up: Expanding the EITC for Adults Without Children

The EITC is a crucial tool that improves the lives of working families with children. But it falls short in boosting working adults without children, thanks to a low income cutoff (only those earning less than $14,880 qualify) and a high age threshold (eligibility begins at 25). As a result, working adults without children are the lone group of Americans that the federal tax code taxes into – or deeper into – poverty.

Expanding the EITC for low-income workers without dependent children would raise their incomes and help offset the impact of other taxes they pay.[19] And in a high-cost state like New Jersey, which leads the nation in the share of 18 to 34 year olds living at home,[20] this EITC expansion would help promote greater economic mobility for young workers, which in turn would help boost the economy.

Thankfully, national leaders from both political parties agree this is a problem. The proposals to fix the problem put forward by House Speaker Paul Ryan, Senator Cory Booker, Senator Sherrod Brown and others would help between 343,000 and 504,000 low-income working New Jerseyans across different ethnic groups and vocations.[21]

Appendix: Impact of Increasing the EITC to 35 Percent by County

Endnotes

[1] New Jersey Division of Taxation, Earned Income Tax Credit Information

[2] New Jersey Office of Revenue and Economic Analysis, Statistics of Income, 2013 Tax Returns, Summer 2015.

[3] NJPP analysis of Brookings Institution, Earned Income Tax Credit Interactive and Resources, Tax Year 2014. Source data available at https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/earned-income-tax-credit-eitc-interactive-and-resources/

[4] Ibid 3

[5] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Tax Increase to Fund Transportation Should Be Combined with Credit to Help Low-Income Families, January 2015.

[6] New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Legislative Fiscal Estimate of A-12, October 2016. Note: NJPP used the low range of the estimated revenue loss for Fiscal Year 2022.

[7] Tax Credits for Workers and Their Families, State Tax Credits, 2016.

[8] Ibid 2

[9] Economic Policy Institute, Family Budget Calculator, 2016.

[10] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy microsimulation model. For more on the methodology, see the Institute’s Who Pays? report: http://www.itep.org/whopays/

[11] Ibid 10

[12] New Jersey Division of Taxation, New Jersey Tax Expenditure Report, February 2016.

[13] Ibid 3

[14] The Brookings Institution, Using the Earned Income Tax Credit to Stimulate Local Economies, November 2006.

[15] Ibid 3

[16] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds, April 2015.

[17] Ibid 16

[18] Brookings Institution, Fighting Poverty at Tax Time through the EITC, December 2014.

[19] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Strengthening the EITC for Childless Workers Would Promote Work and Reduce Poverty, April 2016.

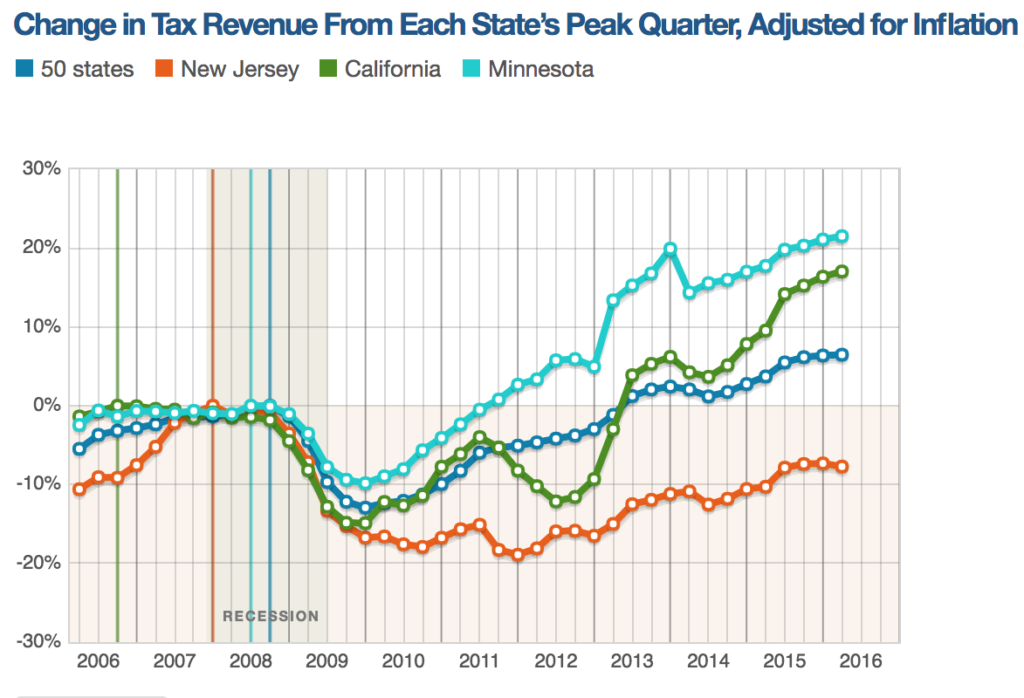

[20] New Jersey Policy Perspective, New Jersey’s Sluggish Recovery Hurting Working Families, September 2016.

[21] New Jersey Policy Perspective, EITC Expansion Would Provide a Crucial Boost to Hundreds of Thousands of New Jerseyans, October 2016.