To read a PDF version of the full report, click here.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is New Jersey’s only program designed to protect low-income families with children during their times of greatest need, acting as a critical bridge to stability and a shield against the harms of deep poverty. Programs like TANF that help stabilize the take home pay of low-income families have long-lasting effects on a child’s ability to succeed in school, get a high school or college degree, and find work as an adult. By increasing the state’s inadequate TANF grant levels, lawmakers could improve maternal and child health, which will have major short- and long-term benefits for families in every corner of the state.

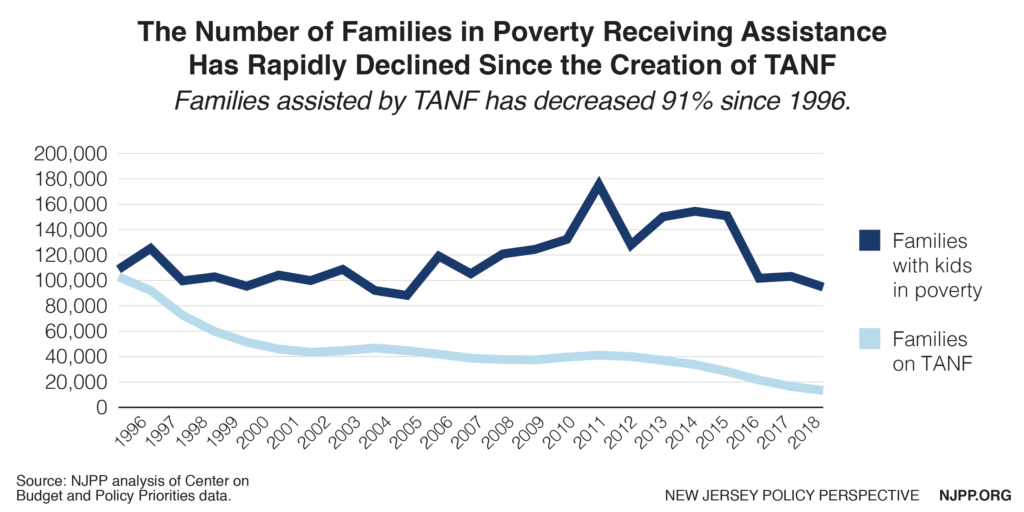

TANF does not provide the full supports that parents need to obtain the jobs that will permanently lift their families out of poverty. In fact, the ability to protect families in deep poverty has been undercut by many state and federal policies. This can be traced back to 1996 when Congress replaced the New Deal-era Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program with TANF block grants. Intended to drastically limit basic assistance to struggling families, the federal TANF law set fixed federal funding, placed a five-year lifetime limit on TANF benefits, implemented punitive and ineffective work requirements, and included other harmful policies that further impoverish children and place enormous stress on families.

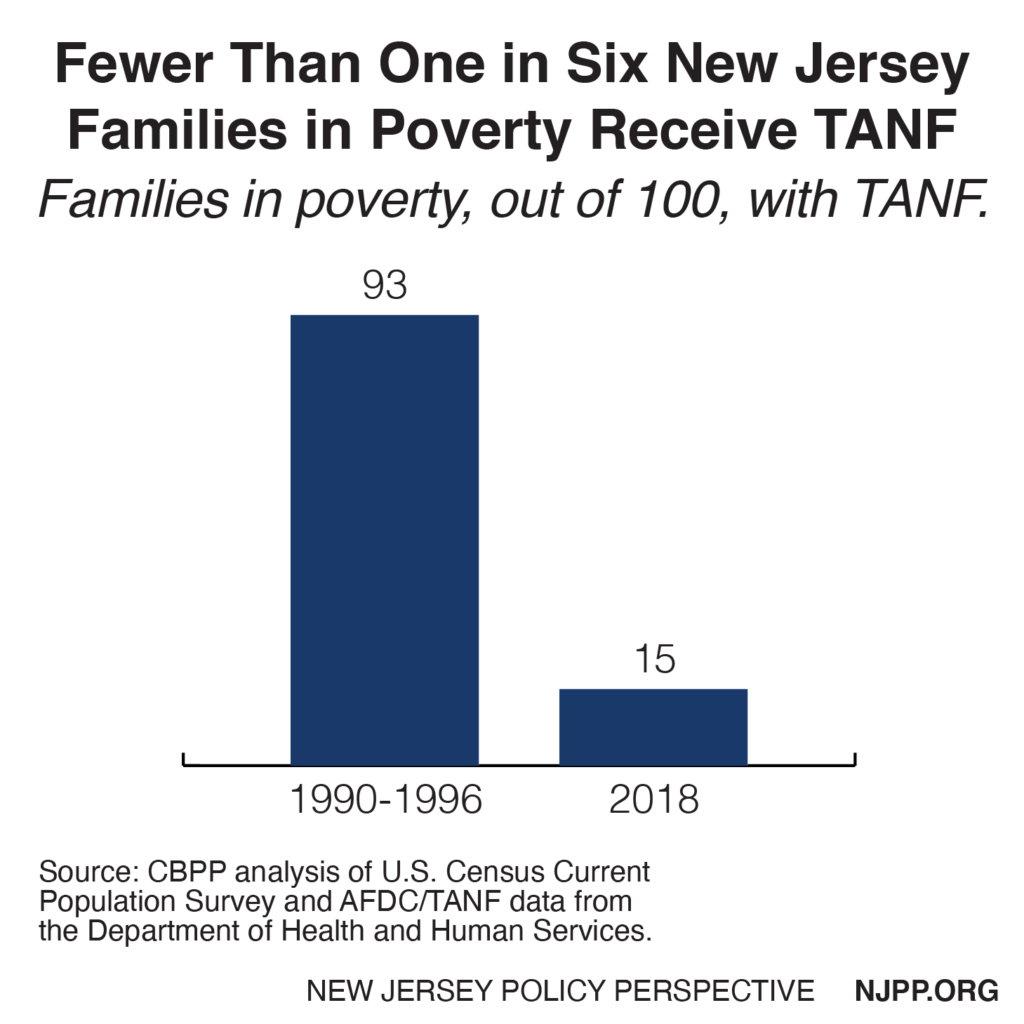

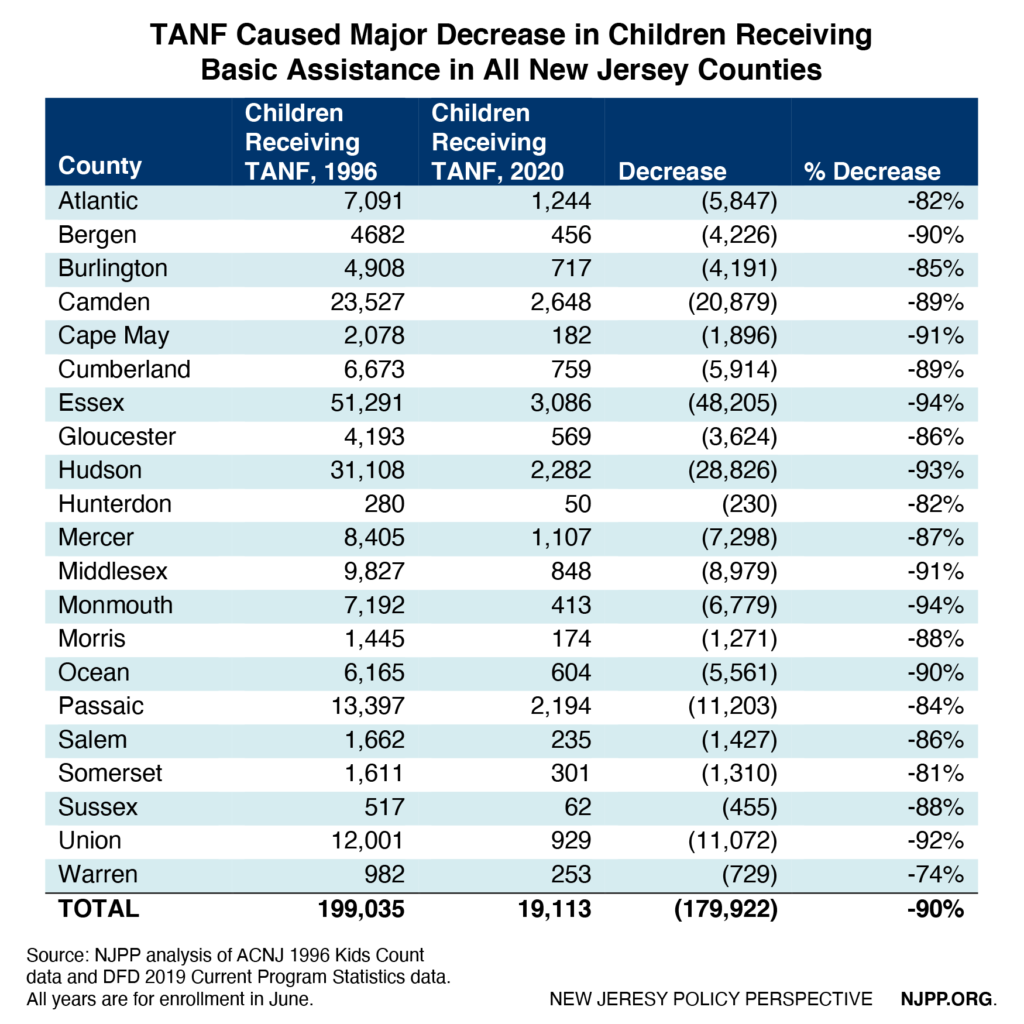

Making matters worse, New Jersey established its own enabling legislation in 1997 (P.L.1997, c.13) with harsher restrictions than required under federal law, resulting in an incredible 91 percent drop in enrollment from 102,000 families in 1996 to 13,000 in 2018. Prior to TANF, New Jersey assisted 93 out of 100 families below the federal poverty level compared to the national average of 72 families out of 100. In 2017-2018, the state was only assisting 15 out of 100 families living below the federal poverty level, which was below the national average of 22 families out of 100. In other words, New Jersey fell from one of the top performers in helping low-income families to one of the worst. The table in the appendix shows the incredible harm that TANF has caused in eliminating basic assistance to 180,000 children by county through 2019.

Despite recent increases in TANF benefits, they remain woefully inadequate for families living in poverty, especially since New Jersey has one of the highest costs of living in the nation. In fact, New Jersey ranks only 32nd in TANF benefits as compared with all states when housing costs are considered.[1] While this is a significant improvement as compared to the rank of 43rd in 2017 before the most recent increases in TANF benefits, New Jersey still has far to go.[2]

By reinvesting in TANF, state lawmakers choose healthier kids, safer families, and stronger communities where everyone has what they need to contribute and thrive. This report describes commonsense changes that would correct some of the flaws in the state TANF program and extend the reach of TANF to help many more families in New Jersey climb out of

poverty.

The good news is that TANF allows states considerable flexibility to make changes in the program. The Legislature and governor have recently started to make improvements in TANF by increasing the assistance levels by 32 percent over the last year through 2020. This is the first increase in three decades and progress that can be built upon. The current administration, under Governor Murphy, is also emphasizing more education and training (E&T) in TANF instead of placing parents in dead-end work activities that lack opportunities to secure employment and long-term economic success. However, much more than that will be needed to turn around a program that was neglected for decades and made worse at the federal level.

The Importance of Reducing Child Poverty

Surprisingly, there is no state statutory goal in TANF to lift families out of poverty. Historically, the practice has been to get families off TANF as soon possible, which often forces enrollees to take any job, even if the pay is inadequate to support a family. Because of this narrow goal, the state has viewed a reduction in the TANF caseload as a success even when child poverty was increasing. This means that families often remain in poverty or even cycle back onto TANF. Research shows that kids who spend most of their childhood in poverty are 45 percent more likely to live in poverty at age 35 than children who live in poverty for only one year.[3] In other words, the less time in poverty, the more likely the cycle of poverty can be broken.

Although New Jersey has increased TANF benefits over the last two years, the state’s historic TANF policy of discouraging full economic opportunity is cruel, shortsighted, and discriminatory. It also does not make any economic sense because the best investment a state can make is in its children. The following are some of the benefits of reducing child poverty:

Reduces public costs in the long run

Chronic poverty causes devastating and long-term harm to children that costs the nation an estimated $1 trillion in economic activity, health, and crime.[4] The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2019 report, “A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty,” provides the first consensus declaration by the scientific community on the causal connection between growing up with adequate family income and positive outcomes for children that lay the foundation for better health and higher earnings in adulthood.[5] We either invest in our children now or pay much more later on.

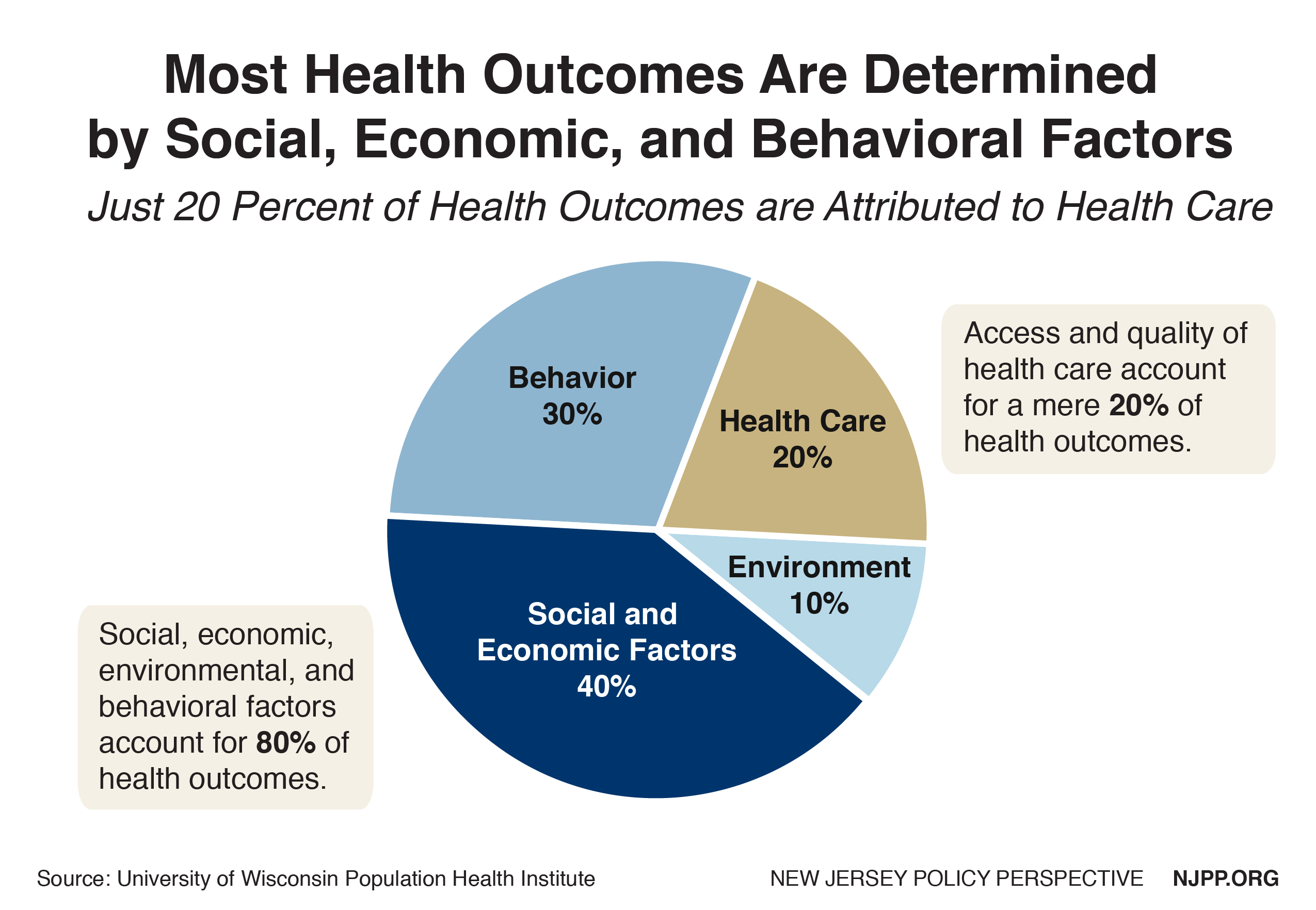

Improves maternal and child health

Extensive research has conclusively shown the strong link between family income and infant mortality and children’s health.[6] Children born to low-income mothers have the highest rate of low birth weight. Children in poor families are four times more likely to be in poor or fair health compared to higher income kids. By directly giving pregnant mothers cash assistance, they have the flexibility to spend more of their limited income on things that lead to better health such as transportation to doctor appointments, safer housing, over the counter medications, diapers, and better nutrition. Improving health for families is especially important in New Jersey given that the state has consistently scored poorly in maternal and child health, especially for Black families. As long as pregnant mothers and parents of newborns suffer the stress of extreme poverty, New Jersey’s efforts to reduce infant mortality will be limited.

Reduces racial and ethnic income disparities.

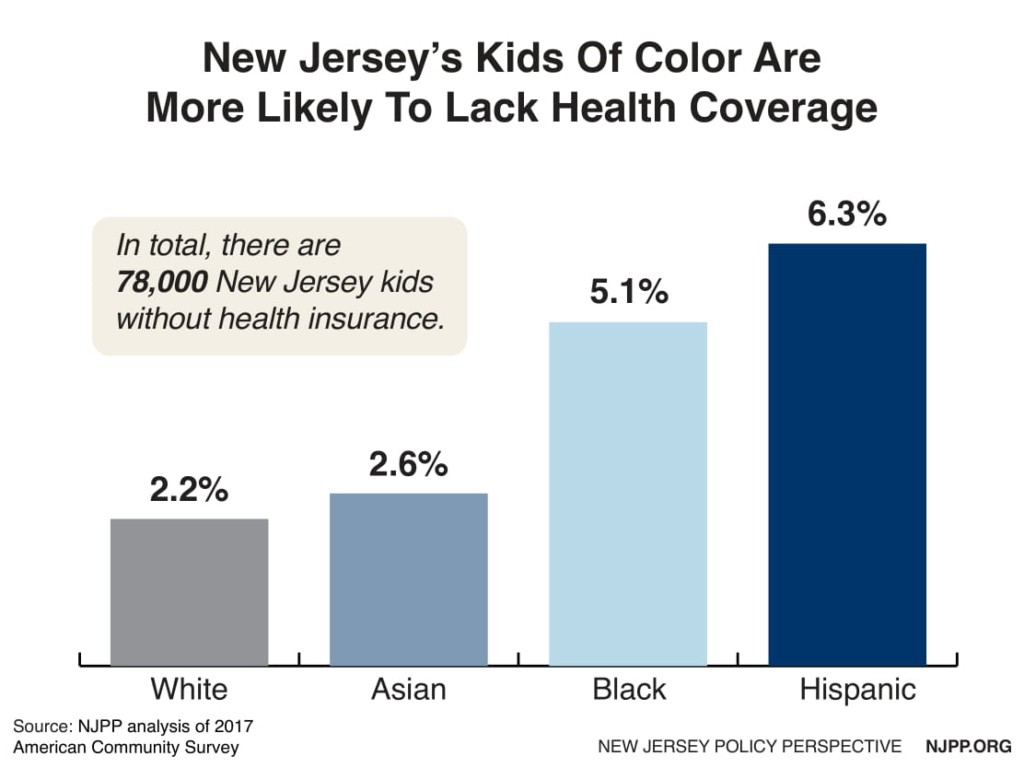

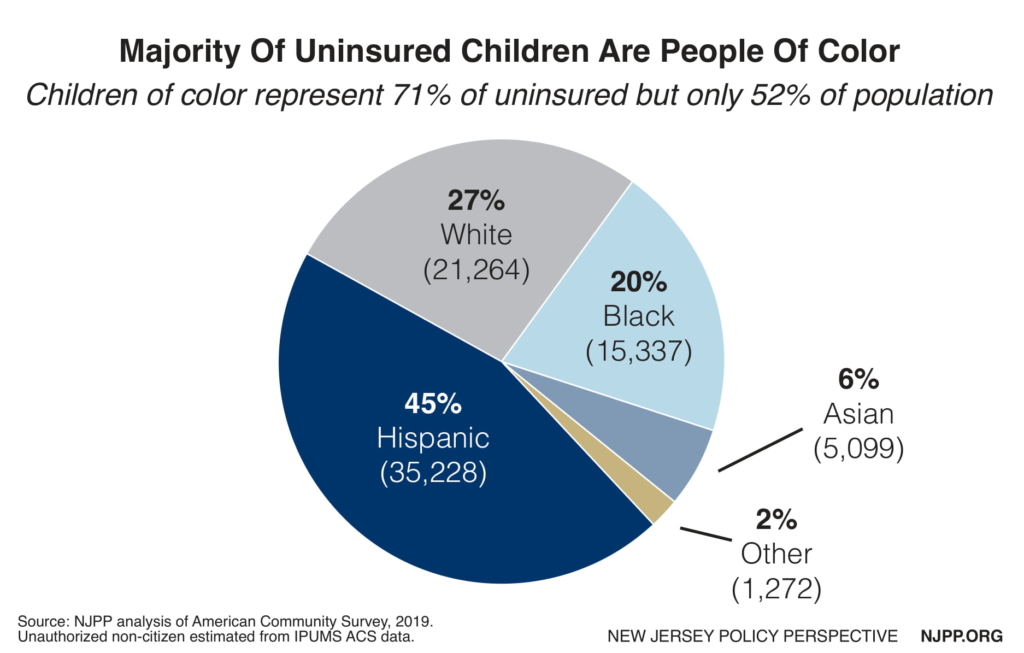

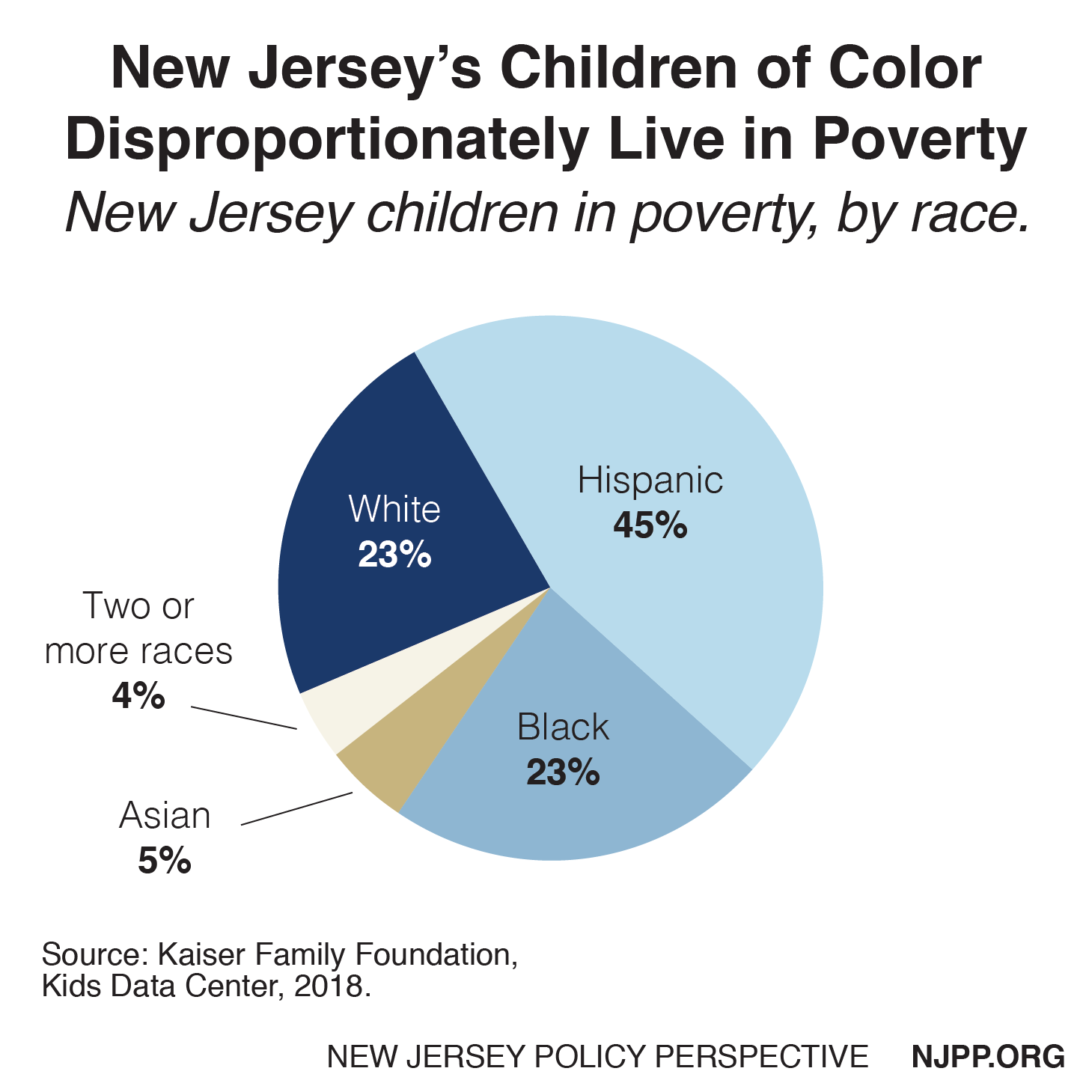

New Jersey is a wealthy state, but wealth is not shared equally or fairly. This is especially true for kids in poverty. Due to historic discrimination, such as in housing, employment, and education, Black and Hispanic kids do not have the same opportunities white kids do. In fact, about two-thirds of all New Jersey children in poverty are Black or Hispanic, as Black and Hispanic children are more than three times more likely to live in poverty than white kids.[7] As a result, 8 out of 10 children on TANF, the poorest of the poor, are either Black or Hispanic. Failure to improve TANF means continuing to discriminate against these kids of color and robbing them of their birthright to equal opportunity. Addressing this problem would also help to reduce major income inequality, where New Jersey is ranked the seventh worst in the nation.[8]

Improves the economy

Child poverty is a drag on New Jersey’s economy and makes the state less competitive because parents are not working or do not have opportunities for good paying jobs. There are also employers who do not want to train their employees because they do not want to invest in them to only have them leave for other jobs, which is also problematic. This could be reduced by improving TANF so it better provides the E&T that parents need. In addition, increasing TANF benefits would stimulate local economies where it is needed the most. Research shows that providing direct assistance to low-income people is one of the most effective ways to stimulate the economy because the money is spent quickly and directly in local communities.[9] State expenditures have decreased by over $5 billion since TANF was established, which has not only harmed thousands of poor families but the economies of low-income communities as well.[10]

Common Sense Measures to Improve TANF

1. Ensure that no families on TANF remain in deep poverty

The current level of NJ TANF benefits ($559 a month for a family of three) is only one-third of the federal poverty level, guaranteeing that families continue to live in deep poverty, defined as below half of the federal poverty level. This remains true despite the state increasing TANF benefits by 32 percent over the last two years. The low benefit level also costs the state more for many families because they cannot afford any housing and end up receiving much more expensive emergency assistance in a shelter or other arrangements to avert homelessness.

Solution: Require a set annual increase in TANF benefits so it reaches 50 percent of the federal poverty level within three years for each household size. For every year after, automatically adjust the TANF benefit for inflation.

2. Get families off the caseload and out of poverty

Historically, the goal of TANF has been to get a family off TANF as soon as possible, regardless of the outcome. As a result, parents are pressured to take jobs that are so low paying or temporary that the family remains in poverty and may be forced to return to TANF. Previous governors, therefore, have measured the success of TANF not by how many families in poverty have been helped but rather how quickly the caseload can be reduced regardless of the number of families that need assistance. This goal has resulted in punitive policies and practices in TANF that can make it a bureaucratic nightmare. The state also does not follow employment or earnings outcomes for families who left TANF to determine if TANF was successful in promoting economic independence.

Solution: In addition to federal TANF goals, the state should add the goal of lifting families out of poverty. To measure that goal, the state should be required to monitor the employment rates and earnings of families that leave TANF, including identifying where TANF leavers fall with respect to various percentages of the federal poverty level.

3. Provide better supports for children

Historically, TANF has focused on parents rather than the whole family. In fact, TANF often punishes children to get their parents to comply with the many TANF rules. For example, if a parent does not meet the rigid work requirements, the parent loses his or her assistance in the second month and the child loses assistance by the third month if the parent is still non-compliant or cannot find suitable employment. Further, if a parent is denied assistance because they have reached the five-year limit, the child is also denied assistance as long as the child lives with the parent. In 2017, benefits were taken away from 328 families who reached the arbitrary time limit.[11] This increases stress and homelessness, which threatens family stability. Continuing to provide benefits to children will increase costs, which could be from state or federal TANF funds, but it is one of the best investments the state can make.

Solutions:

- Only end TANF benefits for the parent when the parent is not in compliance with work activity but continue to provide them to the child.

- Restore parents’ reduced TANF benefits due to a sanction if the parent becomes in compliance within 60 days.

- Allow children to continue to be eligible for TANF even when their parents have reached the five-year TANF limit, encouraging home and family stability. The state can use federal funds so long as no more than 20 percent of caseloads are over the five-year limit. The state can also use existing state funds for these kids.

- Exclude parents from the five-year TANF limit if they have followed all the TANF rules and continue to do so.

- Expand quality childcare and provide adequate information to parents to ensure they can identify such care.

4. Increase child support payments

Currently New Jersey and the federal government keep all the child support that is paid to a family on TANF except for the first $100 a month regardless of how many kids are in the family. In 2020, the state and federal government estimates that they will collect $24 million in child support whereas kids will only receive $2 million in New Jersey.[12] This not only shortchanges the kids who live in deep poverty, it also means that the non-custodial parent is less likely to pay the full support because they know most of it would not go to their child. Recent research shows that when children on TANF are allowed to receive their full child support payments, those payments increase.[13] Therefore, New Jersey should accept the federal government’s offer to waive its share of the child support collected for up to $200 a month (when there are two or more children) when the support is passed through to the family and disregarded as income. This waiver of the federal share of collected support makes increasing the amount of child support passed through to the family at essentially half-price to the state.

Solution: Increase this child support pass through to $200 for families with two or more children, which will benefit the children and encourage non-custodial parents to pay more in child support.

5. Provide the education and training parents need for better jobs

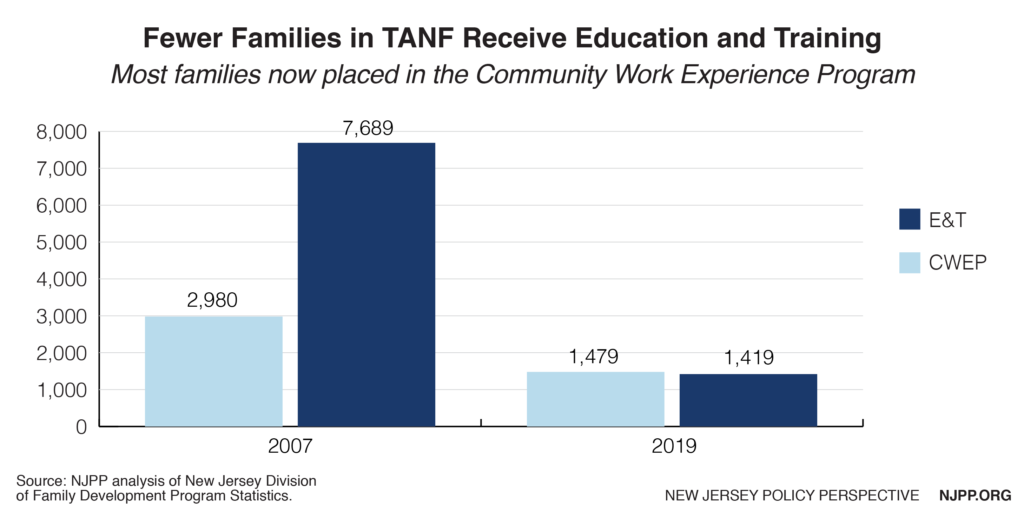

Historically, in order to meet TANF’s work requirements, more parents have been placed by the state, sometimes without pay, in job search activities or the Community Work Experience Program (CWEP) than in education and training programs. This policy too often results in “make work” placements that perpetuate poverty and creates enormous stress for the parents who in some cases have little or nothing to do in their CWEP placement. Unfortunately, because of the declining caseloads due to harsher requirements and greater reliance on CWEP, fewer parents are receiving E&T in TANF.

Solutions:

- Prioritize education and training with the goal of getting parents to qualify for livable wage jobs that lift families out of poverty.

- Expand existing options for E&T to provide parents with the skills that are needed for growing New Jersey industries, such as through apprenticeships, internships, work study programs and other opportunities as well as greater utilization of community colleges. A large body of research has shown that sectoral-based skills training programs can result in major gains in employment and wages for low-income adults who have the most difficulty finding jobs.[14]

- Restrict the time period in CWEP placements to 6 months within any 12-month period.

- Allow placements with for-profit entities to satisfy “alternative work experience,” provided that they are limited to 6 months and will likely lead to full-time employment with the employer.

- Require businesses that receive state tax incentives to collaborate with local community organizations that provide support to TANF participants in the form of work-study, apprenticeships, internships, sector-based contextualized literacy training, skills-based training in growing New Jersey industries, and/or job-retention and advancement services.

6. Eliminating work requirement provisions that are much harsher than required by federal law

Federal rules require a parent to participate in a work activity for 30 hours a week, or 20 hours if their child is under six, but the state goes beyond that by requiring between 35 and 40 hours in unpaid work placements.[15] This higher hourly requirement is not always realistic for parents; for example, a parent who must also take their children on a bus to childcare then take another bus to participate in a work activity. Also, while federal policy allows a state to exempt parents of infants from work activities for up to 12 months, New Jersey only allows three months. The current state requirements often set up parents for failure and make it impossible for them to support and bond with their children, which is critical for their development. TANF sanctions historically have been the leading cause of case closures.[16]

Solution: Consistent with federal rules, allow parents with infants to be exempt from work requirements for up to 12 months, and reduce the current 35-hour week work requirement to 30 hours, and 20 hours if their child is below age 6.

7. Improving case management

Because of the five-year lifetime limit on TANF, it is critical that families receive supportive case management to ensure that the parents have all the resources they need to find good jobs before that limit is reached. Currently, participants who reach their 48th month of assistance must participate in the Supportive Assistance to Individuals and Families (SAIF) program. This program provides intensive case management for families who have been unable to become independent due to multiple barriers to employment.[17] While this has helped some families, it has been reported that it starts too late, and can sometimes mean parents have to meet even more requirements, which can cause them to just give up in frustration.

Solution: Offer additional case management and supportive services, based on an assessment of their barriers to securing employment, once a parent reaches a total of 36 months of enrollment.

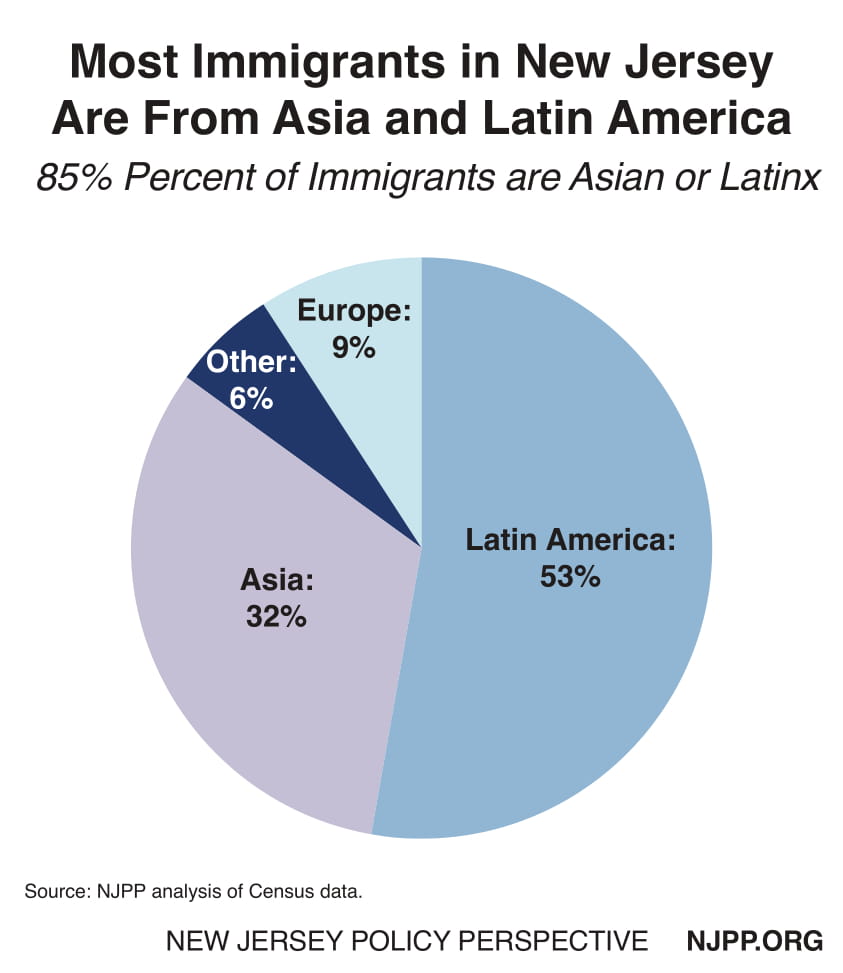

8. Broadening TANF eligibility for lawfully present immigrant families

The New Jersey law sharply limits which immigrant children or parents that are lawfully present in this country are eligible for TANF. For example, immigrant children and parents who have been in the U.S. for five years or less are ineligible for TANF. People who were born outside the U.S. have the same needs as native-born people from New Jersey who live in poverty and should not be discriminated against. Excluding immigrants is also antithetical to the state’s public message that it welcomes them. Moreover, studies have shown that immigrants strongly contribute to the state’s economy.

Solution: Make all immigrant children and their parents who are lawfully present in this country eligible for TANF and who otherwise meet TANF eligibility standards.States can use state funds but not federal TANF funds for those immigrants who were made ineligible or excluded for five years under the 1996 law.

9. Improving the exit ramp off of public assistance to support work

It is important that a family’s TANF benefits be reduced gradually once the parent obtains a job to avoid a “cliff,” which is when a small increase in income from a job causes a disproportionate drop in TANF benefits, causing the family to be worse off financially. This cliff also becomes a disincentive to increasing hours or accepting potential raises. The current policy allows the parent to keep their full TANF benefits in the first month of employment, which is then phased down in subsequent months. The phase down rules differ for part-time and full-time workers, which is confusing for the parents and even the case workers. Simpler policies that also do not start grant reduction until after two months of earnings will allow TANF families time to stabilize their family budget after getting a new job.

Solutions:

- Increase the current incentive for employment by allowing the employed family to receive their full TANF benefits for two months.

- Remove some of the limits on how many times the earnings disregards can be applied.

- No longer count the time receiving TANF due to earnings disregards towards the five-year time limit on TANF. While the federal TANF rules do not have a “stop the clock” provision, a state can choose when to run time or stop time clocks so long as not more than 20 percent of the caseload receive federal TANF funds beyond 60 months. Most working families do not stay on TANF for five years, but if the state chose, it also could simply use state funds to serve families whose clocks are stopped.

Conclusion

Collectively, these policies would provide a boost in basic assistance that gives families needed flexibility to use the income in the ways that best help their household live in a high cost of living state like New Jersey. This means diapers, medicine, clothing, bus fare, school supplies, rent and utility payments, car repairs, and more. Income matters: when Black, Brown, and white families struggling to meet their basic needs get more income, their children have a better chance of growing up healthy and with an opportunity to thrive.

TANF is the main income assistance program for families experiencing extreme financial hardship, and it can play a key role in ensuring that they are able to climb up and out of poverty. When we support the well-being of our neighbors, we make sure that everyone can reach their full potential and contribute to our communities.

Appendix

End Notes

[1] Ashley Burnside, Ife Floyd, More States Raising TANF Benefits To Boost Families’ Economic Security, December 9, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/more-states-raising-tanf-benefits-to-boost-families-economic-security

[2] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, TANF Cash Benefits Have Fallen By More Than 20% In Most States And Continue To Erode, October 13,2017 https://www.publicnow.com/view/71F8C9CD6D0CC646ABAF4FF08EB28C609F63ABC9

[3] Department of workforce services, Inter-Generational Poverty In Utah 2012, Department of workforce services, Inter-Generational Poverty In Utah 2012, https://jobs.utah.gov/edo/intergenerational/igp12.pdf

[4] Michael McLaughlin, Marc Rank, Estimating The Economic Cost Of Childhood Poverty In the United States, March 30, 2018, https://academic.oup.com/swr/article-abstract/42/2/73/4956930?redirectedFrom=fulltext

[5] The National Association of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine; Consensus Study Report, A Roadmap To Reducing Child Poverty, 2019, https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25246/a-roadmap-to-reducing-child-poverty

[6] Stephen Woolf, et al, How Are Income and Wealth Linked To Health And Longevity, April, 2015, wealth https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/49116/2000178-How-are-Income-and-Wealth-Linked-to-Health-and-Longevity.pdf

[7] The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Children In Poverty By Race And Ethnicity In New Jersey, 2018, Richard Barrington, Moneyrates, States with the Lowest And Highest Income Inequality, April 3, 2019, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/44-children-in-poverty-by-race-and-ethnicity?loc=32&loct=2#detailed/2/32/false/37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38/10,11,9,12,1,185,13/324,323

[8] Elizabeth McNichol, How State Tax Policies Can Stop Increasing Inequality and Start Reducing It, December 15, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/how-state-tax-policies-can-stop-increasing-inequality-and-start

[9] Sarah Rinehart, SNAP Is A Boon To Urban And Rural Economies. Proposed Farm Bill Changes Could Cripple Them, July 5, 2018, https://civileats.com/2018/07/05/snap-is-a-boon-to-urban-and-rural-economies-proposed-farm-bill-changes-could-cripple-them/

[10]Raymond Castro, Lost Opportunities For New Jersey Children, February 11, 2016, https://www.njpp.org/reports/lost-opportunities-for-new-jerseys-children

[11] New Jersey Division of Family Development, WorkFirst NJ, Quarterly Progress Update, December 2017, https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dfd/news/wfnj_%20dec17.pdf,

Development, WorkFirst NJ, Quarterly Progress Update, September 2017, https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dfd/news/wfnj_sept17.pdf, https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dfd/news/wfnj_june17.pdf , New Jersey Division of Family Development, WorkFirst NJ, Quarterly Progress, June, 2017, https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dfd/news/wfnj_mar17.pdf

[12] Governor’s FY 2020 Budget.

[13] Colorado Office of Performance and Strategic Outcomes, Evaluating the Effect Of Colorado’s For Support Pass-Through Policy, 2019-2019, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1lh2NsnwZP27eoZEjOPpHtUKMs2qOUW65/view

[14] Tazra Mitchell, Research Note: Sectoral Skills Training Programs For Low Income Workers Can Yield Sustained Earnings and Employment Gains, New Evaluation Finds, June 20, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/research-note-sectoral-skills-training-programs-for-low-income

[15] New Jersey Division of Family Development, New Jersey State Plan For Temporary Assistance For Needy Families, FFY 2015 To FFY 2017, https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dfd/programs/workfirstnj/tanf_state_plan_15-17.pdf, p. 14

[16] In the last quarter alone in 2017 1057 parents were sanctioned, New Jersey Division Of Family Development, WorkFirst NJ, Quarterly Progress Update, December 2017, sanctioned. https://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dfd/news/wfnj_%20dec17.pdf

[17] New Jersey Division of Family Development, New Jersey State Plan For Temporary Assistance For Needy Families, FFY 2015 To FFY 2017, https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dfd/programs/workfirstnj/tanf_state_plan_15-17.pdf, .p.21