To read a PDF of this report, click here.

For more than four decades, policymakers scrupulously observed New Jersey’s constitutional requirements for balanced annual budgets, including prohibitions against long-term borrowing to pay for current needs. The result was a state that emerged from a gray industrial corridor into an economic powerhouse with a modernized transportation system, an expanded network of public colleges and universities, a million acres of preserved open space and a coveted AAA credit rating that kept borrowing costs low for long-term improvements.

Beginning in the 1990s New Jersey changed course, heading down a path of political convenience and irresponsible financing. Doing so has starved the capacity of state government to maintain and expand the assets that give New Jersey unrivaled economic advantages, threatening the state’s economic future.

Nine key decisions have driven this downward spiral. Both major political parties and all three government branches contributed to the failure. Behind each decision were two unstated assumptions: that policymakers can promise essential services without bothering to pay for them, and that future taxpayers should bear the burden for today’s spending even though they will not benefit from it. At the heart of this duplicity is the intentional, systematic and large-scale raid by governors and legislatures of both parties of the assets that had been set aside for the funding of pensions and retiree health benefits for hundreds of thousands of public employees. The New Jersey Supreme Court abetted this massive, fraudulent raid.

These decisions have contributed to the hollowing out of New Jersey’s middle- and working-class families. Property tax relief declined significantly, while property taxes continued their rise. The cost of a public college education rose dramatically as state operating support tumbled, leading to higher tuitions and higher student debt.

The result is that New Jersey’s future as an economic powerhouse with abundant opportunities is in peril. The assets that help build New Jersey’s strong economy – like its location, transportation networks, well-educated workforce, growing population of striving immigrants and excellent public schools – are being neglected, ignored or even savaged.

We need to be clear about the origins of New Jersey’s tailspin, and it is not, as we’re constantly told, high tax rates. In fact, New Jersey’s desperate economic and financial condition is a product of leaders postponing or simply evading their constitutional responsibilities.

There is no simple, easy solution and no one should expect that in any one governor’s tenure New Jersey can fully correct two decades of reckless financial practice or make all the public investments essential to restore prosperity. However, if policymakers persist with politically convenient gimmicks and policies, New Jersey’s condition will only worsen. Acknowledging the origin and magnitude of the state’s decline would be a courageous start – but only a start.

1. 1994-1996: Significant Income Tax Cuts Lead to Large Property Tax Increases

Despite decades of politicians’ promises to fix the problem, New Jersey has the nation’s highest property taxes. The 2014 median tax bill of $7,452 per year was far ahead of second-place Connecticut ($5,369) and the national average ($2,139).[1] So, when New Jersey’s income tax was enacted in 1976, a state constitutional amendment guaranteed that every penny collected would relieve residential property taxpayers. The income tax is a fairer tax, tied to ability to pay: Those with higher incomes pay a larger share of their income than middle-class or low-income residents. Unlike the property tax, if one’s income declines, so does her tax bill.

Gov. Whitman won the 1993 gubernatorial election, in part, on her promise to cut the income tax; a 30 percent income tax cut was phased in over three years beginning in 1994.[2] The financial impact was huge. New Jersey lost about $14 billion in revenue in the first 10 years, reducing the amount of money available for property tax relief.[3]

Bottom line: Gov. Whitman’s tax cuts greatly reduced the funds available to assist local governments and schools and shortchanged property tax relief programs for senior citizens, veterans, the disabled and moderate- and low-income homeowners and renters.

2. 1994 Pension Changes Shift Current Costs to Future Taxpayers

To help plug the budget hole created in part by the income tax cut, the Whitman administration reduced the contributions of state and local governments to the state pension system by $3.5 billion over four years.[4] As of 1993, these assets were more than sufficient to cover the current and future obligations for both pensions and retiree health benefits for state and local public employees. Just three years following enactment of the Pension Reform Act, pensions’ unfunded liabilities multiplied more than five-fold, to $4.2 billion from $800 million.

This sharp break with conservative financial practices started the failure of all three branches of state government to make promised pensions secure at the same time they compounded the problem by increasing future pension benefits without finding the money to pay for them.

In essence, this was accomplished by back-loading the pension system. New Jersey reduced the amount of money it invested for current and future pension payments, and changed the rules so the state would have 60 years to catch up with its earlier underfunding rather than 40 years.[5] This meant that the state could contribute far less each year through the 1990s and early 2000s, but would have to pay more and more in later years just to catch up.

This steady stream of pension payment “holidays” for state and local governments had consequences. While public employees paid in every penny required, new laws lowered their annual payments. This contributed to a growing unfunded liability. But far worse was that governors and legislatures failed to appropriate the full employer payment each year beginning in 1994, passing the financial obligations to future governors, legislatures and taxpayers. The amounts now required are staggering, particularly given the state’s slow crawl out of the Great Recession. Time is running out. As it stands now, within 11 years the state won’t have the money it owes to retired teachers. The timeline is even tighter for other civil servants – eight years.[6]

Since pension fund accounts are large pots of money that aren’t due to be spent right away it’s not surprising that they also became attractive ATMs for political leaders who wanted to increase spending without providing the revenues to pay for it. And like mammoth Alaskan glaciers that slowly recede as average temperatures begin to rise, with only a few scientists noticing, it took a while for the impact of pension fund raids to be seen. After a while, though, study commissions and Wall Street credit rating agencies sent out clear warnings that this dangerous practice jeopardized the state’s ability to pay retirees what they would be due. Unfortunately, it was a relatively low-profile issue. No one’s re-election was threatened by their short-term but reckless decisions. And like the melting glaciers that are helping to raise sea levels that endanger coastal areas, by the time the obligations for spectacularly large annual payments were acknowledged, the shortfall was too large to be addressed absent radical, punishing actions.

Adding to the increased risk, the assumed rate of return on pension assets had been increased two years earlier from 7 percent to an aggressive 8.75 percent.[7] Assuming more aggressive returns on investments meant that less money had to be set aside today.

Made at a time when the stock market was entering a bullish period, the Whitman administration cited recent gains as proof that it was prudent to expect higher investment returns and to reduce payments accordingly. But, of course, markets rise and markets fall. For example, in the 10 years ending in 2012, the average public pension fund rose by 6.4 percent a year; even the best-performing funds rose by just 8.1 percent.[8] By assuming such a high rate of return, successive administrations were able to reduce their contributions while falsely “guaranteeing” that current and future pensions were secure.

But the gains were temporary, and the math didn’t work. Twenty years later the unfunded liability – the amount not available to make guaranteed pension payments – had grown 17-fold to a whopping $80 billion.

Bottom line: The switch in methodology and changed assumptions led to reduced contributions by New Jersey state and local governments, growing the gap between assets required for future payments to $4.7 billion in 1995 from $800 million in 1993.[9] What is worse is that annual employer contributions were held down for more than 15 years, presenting today’s taxpayers with a bill that is impossible to pay. All this means that even if the state contributes the full annual required payment as revised in 1994, the pension fund assets will never be adequate to pay the pension obligations.

3. 1994 Retiree Health Benefits Fund Raid and Conversion Frees Up Cash for the Tax Cut But Puts Health Benefits on Shaky Foundation

Until 1994, retiree health benefits were funded much like pensions – through employer contributions and the compounded returns from investing those contributions in stocks, bonds and other assets. The 1994 law that shifted pension costs to future taxpayers also switched retiree health benefits, requiring the state to put into each year’s budget the amount needed to pay benefits for current retirees. Obviously, as the number of retirees grew, so would the cost to the state.

Making this switch allowed the Whitman administration to empty the $300 million fund that had been built up to pay for these future benefits and – because relatively few retirees were eligible for health benefits – to pay far less each year. Both of these helped plug the budget hole that was created, in part, by the 30 percent income tax cut.[10]

By shifting future costs of retiree health benefits to future taxpayers and raiding the assets in place, Gov. Whitman reduced their costs in her first-term budgets by almost $1 billion.

Health benefits that retired public employees earn after their years of service are no different than pensions, in that they are obligations for which assets should be invested to cover agreed-to payments. The 1994 changes resulted in billions of dollars not being invested that led to the unfunded liability exploding: A $2.3 billion hole in 1994[11] has grown about 29 times larger to where, today, the unfunded liability sits at $65 billion.[12]

Bottom line: Zero dollars are available from investments that were never made after 1994 and the state is on the hook for $65 billion in benefits that must be paid from the general fund at the expense of services vital to New Jersey. In 2016, the payment for both active employees and retiree health benefits was $3.3 billion or 9.7 percent of the state budget.[13] In 1995, it was 3 percent of the budget.

4. Facing Growing Pension Hole in 1997, New Jersey Turns to Reckless Borrowing

The consequences of these major changes to New Jersey’s pension system quickly became apparent, leading to an even more radical proposal. Seeking to tame rapidly growing unfunded liabilities without having to dramatically increase the state’s annual contribution to the pension funds, Gov. Whitman turned to Wall Street, borrowing $2.8 billion in the form of a bond to reduce a liability that had been largely created by the 1994 changes. This was the first time any state borrowed money on that scale to cover a pension liability (a record that lasted until 2003, when Illinois borrowed $10 billion).[14] Now New Jersey could cover more of what it owed over just three years, and pass the very large bill of $10.3 billion to future taxpayers for 31 years.[15]

State and local government employers were allowed to skip required pension payments, their share being partly made up by the money borrowed from Wall Street. The idea was for New Jersey to use the bond proceeds, plus the assumed investment gains from the pension system, to eliminate most of the $4.2 billion unfunded liability.

But it was a ticking time bomb. Sixteen years later, New Jersey taxpayers still owe $2.3 billion of the $2.8 billion borrowed – with interest on top – and annual payments are scheduled to approach $500 million annually by 2020.

The pension obligation bond is three times larger than the next largest borrowing in New Jersey’s history.[16] It also has the most expensive payback, because it carries a permanent interest rate of 7.65 percent and, unlike all other bonds issued by the state, cannot be refinanced to take advantage of lower interest rates. Most importantly, while other bond issues produced tangible products with long-lasting benefits such as roads, sewers or parks, the pension bond produced nothing of lasting value – only a very expensive IOU.

The consequences were immediate and negative. Legislation accompanying the bond act authorized yet another pension payment holiday. From mid-1999 to mid-2006, the state paid in, on average each year, just 4 percent of what was required to keep the pension system healthy (about $23 million a year instead of $600 million).[17] Local governments were given a total or partial contribution holiday over the same period. The $2.8 billion from the pension bond was much too little to meet the payments required over seven years or to fully erase the unfunded liability zooming upward as a result of 1994’s pension changes.

Gov. Whitman told New Jerseyans this borrowing would lower taxes, relieve long-term debt and guarantee the long-term health of the pension fund – while saving taxpayers about $45 billion over 60 years.[18] She asserted that borrowing to pay for pensions was just like a home mortgage, but forgot to mention that one could sell their home to pay off the mortgage after having years of shelter.[19] Pension debt left nothing to sell and no tangible asset. And her administration suggested it came with virtually no risk, “even if there were an economic slowdown.”[20]

In fact, this turned out to be wishful thinking. The stock market boom soon collapsed with the puncturing of the tech bubble. From the end of 2000 through 2003, the assets in the pension funds crashed by 25.3 percent, wiping out $21.7 billion.[21] This reversed the gains from the state’s heavy investments in technology stocks and left the pension funds with a greatly reduced asset base. The end result: billions in future payments were left to taxpayers to both repay the bonds and make up for the assets lost for investment returns.

Bottom line: This year, taxpayers will pay $348.6 million to repay bondholders for covering the employer’s pension costs due in 1997 and 1998 at an interest rate of 7.65 percent.[22] That is stunning by today’s interest rates. The total bill over 31 years will be $10.3 billion.[23] For all that, there is no essential product – no highway, rail line or university facility – to show for it.

5. The New Jersey Supreme Court Opens the Floodgates to More Bad Borrowing

Edison Mayor George Spadoro immediately challenged the pension obligation bond in court, arguing that the New Jersey Constitution prevents the state from going into debt without voter approval except in emergency situations. This offered the Supreme Court the opportunity to prevent an almost doubling in New Jersey’s debt in one day, not a penny of which would be invested in highways, public transit, research facilities or open space – the sole uses of previous bond sales. The Court passed up the opportunity.

Under what is called the Constitution’s Debt Limitation Clause, the legislature is not allowed to create new debt that binds future legislatures without approval by public referendum. The Appropriations Clause prohibits the legislature from making any appropriations of the state’s revenues beyond a given fiscal year or counting borrowed funds as “revenues.”[24] Yet, over the years, the courts had interpreted these clauses in a number of cases to allow the state to take on debt for toll roads, state office buildings and sports stadiums without going through the voters, primarily because a solid stream of dedicated revenues was identified to repay the debts and the state was not on the hook formally to repay the debt.

A New Jersey Superior Court judge turned Spadoro’s challenge away, ruling that the bonds did not create any debt binding future legislatures because they were issued by the Economic Development Authority, an “independent” state authority. A divided appellate panel upheld this decision days later.

These decisions were based on three questionable assumptions: That the EDA is “independent,” that the EDA’s funding was separate from the state’s general fund and that there was no distinction between bonds issued for capital projects and those issued for the “ordinary” functions of government, such as making employer contributions to the pension funds.[25]

The New Jersey Supreme Court quickly announced the controversy moot as the plaintiff had filed his appeal after the bonds had been sold (only 20 days passed between the law’s enactment and the bond sale). Because the transaction could not be “undone” even if the Court found in Spadoro’s favor, the Court refused to act on the appeal. Justice Alan Handler, one of the two Justices to file a partial dissent, believed the Bond Act violated the Constitution’s Debt Limitation Clause. He did not mince words:

“The apparent assumption underlying the [Pension Obligation] Bond Act is that the restrictions of the Debt Limitation Clause may be avoided merely by … substituting an independent authority … as the issuer of debt, even though the authority has no genuine independence,” he wrote. “Under no circumstances should [the Debt Limitation Clause] be deflated or readout of the Constitution as a mere nuisance provision that serves no purpose except to define an administrative procedure for selling debt.”[26]

Before the 1997 Supreme Court decision, voters had approved almost half of the state’s total debt ($3.8 billion of $8.1 billion). Ten years later, New Jersey’s debt had ballooned to $32 billion with just 10 percent of it ($3.1 billion) having been approved by voters.[27]

Bottom line: With the pension bond decision, the New Jersey Supreme Court opened the floodgates for an unprecedented run-up in debt without public approval, which accelerated the deterioration of the state’s financial stability.

6. Pension Benefits are Increased Without the Means to Pay for Them

In the early 2000s, the combination of the state Supreme Court’s decision, successive governors and legislatures that failed to provide the revenues to meet pension obligations and a run-up in the stock market created a new culture of financial irresponsibility in Trenton.

Acting Gov. DiFrancesco, who took over when Gov. Whitman resigned to become the administrator of the federal Environmental Protection Agency, increased pension benefits in 2001 by 9 percent for current and future retired teachers and other civil servants, and simultaneously reduced employee contributions by one-third.[28] The pension increase applied to all active public-sector workers and current retirees, even though those retirees had contributed nothing to the increase. The move was more popular than it was prudent. For one thing, it was built on the premise of a strong stock market that had already begun a significant decline.

To pay for these changes, the governor and lawmakers created their own time machine and their own actuarial rules. Since markets were beginning to decline as the dot-com boom was punctured, the bill reached back for the market value of pension assets two years earlier on June 30, 1999. The governor and legislators decided to capture the difference between the pension fund’s market value on that date and the value that actuaries reported, which was $5.3 billion lower for the teacher pension fund alone.[29] Actuaries are careful to smooth out the volatility in markets by typically taking a three-year average of the market value of assets, hence the $5.3 billion difference. The state carved out a separate “Benefit Enhancement Fund” for each of the two largest pension funds that were to be funded from the inflated and historical market values to pay for the newly increased benefits.[30] If these enhancement funds turned out to be inadequate to cover the increased pension payments, the statute required the state to make up the difference with larger annual appropriations. It turned out that the funds were inadequate, but the significant increased appropriation requirement was ignored year after year.

There was another problem. Between June 1999 and the time the bill was signed into law in 2001, the pension assets had already declined by $4.2 billion as the stock market moved downward.[31] This meant that the difference between actual and actuarial asset calculations had shrunk significantly, but that in no way was reflected in the fictional values assigned to the benefit enhancement funds.

This legislation may have been politically popular, but it accelerated New Jersey’s financial deterioration. It also earned New Jersey the dubious distinction of becoming the first state ever charged with violating federal securities laws.

In 2010, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission charged New Jersey with fraudulent misrepresentation in its disclosure statements to sell $26 billion in bonds that followed enactment of the 2001 law.[32] The SEC charged, and New Jersey agreed, that the state falsely asserted it made required payments, disguising the underfunding of its two largest pension funds. “The state’s bond offering documents lacked sufficient information for investors to understand the state’s historical failure – since 1997 – to contribute [to the funds],” the SEC noted.[33]

Among the SEC findings:

- The New Jersey Office of Legislative Services’ fiscal note that was issued two weeks after the law was signed documented that had the most recent quarterly valuation of assets been used, it would have shown a decline of $2.4 billion.

- The statutory revaluation “created the false appearance that the plans were ‘fully funded’ and allowed the State to justify not making contributions … despite the fact that the market values of the plans’ assets were rapidly declining.”[34]

- Starting in 1997, New Jersey consistently ignored actuaries’ calculations for employer contributions, instead treating withheld payments as “savings” to be used elsewhere.[35]

- The state recycled funds between the Benefit Enhancement Funds and supposed reserve funds, creating “the false appearance that the State was making contributions to [the pension funds], when no actual contributions were being made.”[36]

Bottom line: In an unorthodox action, New Jersey granted a 9 percent increase in pension benefits that was funded by capturing asset values posted on one day two years earlier and using that value to claim that payments would be made for the increased benefits. New Jersey earned the distinction of becoming the first state to be charged with fraudulent misrepresentation by the SEC.

7. Long-Term Borrowing to Plug Short-Term Budget Holes Ramps Up

Between a 52 percent overall spending increase in the eight Whitman-DiFrancesco years, the bursting of the dot-com bubble with its trailing recession and the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, New Jersey faced a $5.3 billion shortfall in the budgets for fiscal years 2002 and 2003. Gov. McGreevey, like his two immediate predecessors, borrowed to cover operating expenses. To start, his administration used proceeds from the recent tobacco settlement to help reduce the state budget deficit.

In November 1998, attorneys general from 46 states settled their lawsuits against the tobacco industry for smoking-related health care costs that landed on the states’ doorsteps. The agreement required tobacco companies to make payments to the plaintiff states estimated at $206 billion over 25 years.

New Jersey found an innovative way to spend the tobacco money without having to wait 25 years. Like a handful of other financially distressed states, New Jersey sold bonds to plug budget holes, pledging to repay this borrowing over 12 years out of the yearly proceeds from the tobacco settlement. This “tobacco securitization” granted the bondholders some or all of the revenue from the tobacco settlement to cover the repayments. By foregoing a steady stream of revenue 12 years into the future, Gov. McGreevey was able to generate $3.4 billion to help balance two budgets.

If that sounds risky, that’s because it is.

Because future administrations and taxpayers would be deprived of those revenues while significantly increasing the state’s debt burden, New Jersey received downgrades in its credit ratings from the three major credit rating agencies.

Once again, the New Jersey Supreme Court had the chance to affirm the Debt Limitation Clause in a challenge by Bogota Mayor Steve Lonegan to the tobacco securitization and other “contract bonds.” And once again, it chose not to “disrupt the state’s financing mechanisms,” ruling “that the restrictions of the Debt Limitation Clause do not apply to appropriations-backed debt.”[37]

The McGreevey administration was not done borrowing long-term to meet annual budget shortfalls. Faced with another potential deficit in the 2005 budget, Gov. McGreevey increased corporate business tax rates and when it was clear that the higher revenues wouldn’t fill the gap, his administration swapped the future revenues from a tax increase on cigarettes and new driver fees for a one-time infusion of cash from a bond sale to help balance the budget.

The new bond sales helped plug the hole by raising an estimated $1.9 billion for the 2005 budget.[38] But instead of the new revenues (estimated at $185 million per year)[39] going into the general fund to support higher education, Medicaid or other priorities, it would go exclusively to bond buyers for 24 to 30 years.

Just days before Gov. McGreevey was to sign the budget, Republican legislators led by Senate Minority Leader Leonard Lance sued to halt the sale of the bonds. They objected to borrowing to balance the budget, but without specifying the budget cuts they would make to avoid the borrowing. Such a scheme would be a burden on future legislators, governors and taxpayers, they argued, and may violate the Constitution’s Debt Limitation and Appropriation Clauses.

A Superior Court Judge ruled that the state could proceed because it had designated two new sources of revenue to cover the bond repayments. The matter was quickly brought to the Supreme Court, which was presented with a fourth opportunity to enforce the Constitution’s Debt Limitation Clause.

Bottom line: Liberated by earlier Supreme Court rulings, Gov. McGreevey executed two “securitization” deals that used long-term debt of $5.3 billion to help balance three budgets.

8. The New Jersey Supreme Court Keeps Blessing Dangerous Financial Practices – Until it is Too Late

The state Supreme Court wasn’t done unwinding the force of conservative constitutional financial mandates with its failure to take up the pension obligation bond. Twice before the case on Gov. McGreevey’s borrowings was heard, the Court was given clear chances to reaffirm the strict boundaries of the clause and twice it passed.

Faced with a 2002 case challenging the issuance of “appropriation” and “contract” bonds, which relied entirely on the good faith that future legislatures would appropriate whatever funds were required for repayment, the Court set aside the question with the exception of bonds to build schools in the 31 Abbott districts (that the Court had ordered in 1995 to receive 100 percent funding for facilities) and to cover up to 40 percent of non-Abbott district capital projects. Effectively, the Court ruled that the Debt Limitation Clause was trumped by the requirement that all children are entitled to a “thorough and efficient” education that includes adequate facilities.[40]

The Court’s decision to protect funding for school facilities was built on a foundation of sand. First, it asserted that school construction bonds were not an obligation of the state, but of the Economic Development Authority, and that bond buyers and credit agencies therefore would not expect the same security as a voter-approved general obligation bond. Second, it assumed that the meager assets of the Fund for the Support of Free Public Schools – which stood at about $100 million – would be sufficient to guarantee repayment of the $2.6 billion in bonds to cover the non-Abbott districts.[41]

Meanwhile, the Court ordered a new hearing on other contract bonds like those issued by the Transportation Trust Fund. A year later a closely-divided Court decided to uphold the surge in appropriation and contract bonds, declaring that when the state was “highly likely” or “obligated” to repay them, it did not fall within the boundaries of the Debt Limitation Clause, even without a dedicated source of revenue.[42]

While the Court failed to halt the surge in contract or appropriation bonds for purposes ranging from school construction to football stadiums to transportation, in the Lance case it finally drew a line on borrowing long-term solely for the purposes of balancing the annual budget.

New Jersey’s Supreme Court overruled the Superior Court opinion, calling the McGreevey bond sale unconstitutional and banning the state from borrowing money to balance the budget – but not until the following fiscal year. “Disruption to the state government,” said the Court majority, overrode the Constitution.[43] This allowed Gov. McGreevey to sell the bonds while protecting all earlier bonds that employed the same device that it now ruled as unconstitutional.

Specifically, the Court rightly found that contract bond proceeds used to fund general expenses in the state budget did not constitute “revenue” and could not be used to balance the budget. However, because the Court had previously ruled otherwise, the holding was applied only to future budgets because aborting the bond sale would have required significant revisions to, if not a complete overhaul of, the 2005 budget.

Bottom line: After seven years and four decisions, the New Jersey Supreme Court finally decided that the Debt Limitation Clause means debt cannot be issued to help balance annual budgets unless approved by public referendum. “Likely appropriations” are no longer a sufficient basis to evade the clause – except in this one case (and all preceding cases).

9. Money for Long-Term Improvement of Key New Jersey Asset Grabbed to Cover Current Costs

Gov. Christie in 2010 withdrew New Jersey’s support for an additional rail tunnel between New Jersey with Manhattan, directing the Port Authority to allocate funds committed to the “Access the Region’s Core” (ARC) tunnel to be redirected to highway and bridge projects in North Jersey. The move allowed the governor to delay addressing the looming Transportation Trust Fund crisis.

That decision compromised New Jersey’s most important economic asset: its location in the middle of the world’s largest market with convenient access to New York City and Philadelphia. No competing state can replicate this advantage, which only works if an efficient transportation network is in place to move people and goods.

The ARC project would have created a more convenient and reliable commute by building a two-track rail tunnel between New Jersey and Manhattan and a new NJ Transit rail terminal in midtown Manhattan, enabling NJ Transit to at least double the number of rush-hour trains.

The ARC cancellation enabled the Christie administration to direct the Port Authority to shift the tunnel money to other projects, in the process avoiding a much-needed increase in New Jersey gasoline taxes to finance transportation projects. The $1.3 billion in ARC funds reallocated to highway and bridge projects in North Jersey meant the governor could ignore the pending bankruptcy of New Jersey’s Transportation Trust Fund, which pays for capital road, bridge and transit projects around the state and which ran out of money for new projects this summer.

By canceling the ARC project, New Jersey gave up at least $3 billion in federal aid and missed an enormous economic opportunity. It would have created thousands of jobs just as New Jersey was starting to crawl out of the Great Recession and substantially increased property values in towns with train service to New York (and, thus, property tax revenues). It would have encouraged new developments near train stations that would have boosted the economy and significantly reduced the number of polluting cars on the road. Moreover, the Port Authority and New Jersey could have locked-in historically low interest rates that would have saved tens of millions in bond repayments in the future.

Amtrak has since proposed its Gateway tunnel project to replace ARC, but it is still in the planning stage. Once approved, its earliest completion date is 2030, 12 years later than the projected completion date of the ARC project. The realization of this project will still require a significant contribution from New Jersey. Gov. Christie has now endorsed the Gateway project and approved the Port Authority’s participation.

Bottom Line: New Jersey’s greatest economic asset – its location – has been severely diluted by the ARC cancellation. The draw of diverse residential communities with some of the nation’s best public schools and easy access to New York will dwindle once commuter rail service is sharply reduced with the pending shutdown of single-track tunnels for unavoidable repairs.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates, Mortgage Status by Median Real Estate Taxes Paid.

[2] Disclaimer: Co-author MacInnes was one of four legislators to vote against all three tax-cut bills.

[3] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Was It Worth It? Looking Back on a Decade of Income Tax Cuts, March 2005, p.1.

[4] Plansponsor Magazine, Whitman’s Bruising POB Fight: The New Jersey Governor Pushed Through a Record $2.75 Billion Issue, Only to Face a Lawsuit and a New Issue For Her Next Reelection Campaign, September 1997.

[5] New York Times, Whitman’s Borrowing Plan: Criticism May Not Go Away, June 1997.

[6] Moody’s Investors Service, Issuer Comment: New Jersey (State of): New Jersey Reports Surge in Unfunded Liabilities Under New Pension Accounting Rule, December 2014.

[7] State of New Jersey Benefits Review Task Force, Report of the Benefits Review Task Force to Acting Governor Richard J. Codey, December 2005, p.10

[8] Cliffwater, LLC, 2013 Report on State Pension Performance and Trends, July 2013.

[9] Barbara and Stephen Salmore, New Jersey Politics and Government: 4th Edition, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2013, p. 206

[10] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Take the Money & Run: How Fiscal Policy From the ‘90s to Now Threatens New Jersey’s Future, 2001, p. 31

[11] Ibid 10, p. 30

[12] Politico New Jersey, Fitch Reaffirms State’s Credit Rating, But Unfunded Liability Still Concerning, March 2016.

[13] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Budget in Brief, Fiscal Year 2016, p. 10

[14] Pro Publica and Washington Post, How Illinois’ Pension Debt Blew Up Chicago’s Credit, May 2015.

[15] State of New Jersey, New Jersey Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,Fiscal Year 1997, p. 9

[16] The 2000 bond sale by the Transportation Trust Fund comes in second, at $900 million.

[17] New York Times, Behind Fraud Charges, New Jersey’s Deep Crisis, August 2010.

[18] Fortune Magazine, The Public Pension Bomb, May 2009.

[19] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Budget in Brief, Fiscal Year 1998. p.47

[20] Tom Bryan, The New Jersey Pension System, p. 350 in Pensions in the Public Sector, edited by Olivia S. Mitchell and Edwin Hustead, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

[21] Ibid 7, p.10

[22] State of New Jersey, Annual Debt Report, Fiscal Year 2014, p.21

[23] Ibid 15

[24] N.J. Const. art. VIII, § 2

[25] Spadoro v. Whitman, 150 N.J. 2 (1997) 695 A.2d 654 at 11

[26] Ibid 25 at 13

[27] New York Times, Corzine’s New Equation: Tolls Up, Borrowing Down, November 2007.

[28] P.L. 2001, c. 133

[29] The New York Times, N.J. Pension Fund Endangered by Diverted Billions, April 2007.

[30] Philadelphia Inquirer, Since 1992, Governors Have Been Shortchanging N.J. Pension Fund, September 2010.

[31] Ibid 7, p.11

[32] State of New Jersey, Exchange Act Release No. 9135, 2010 WL 3260860 (Aug. 18, 2010) [hereinafter Exchange Act Release No. 9135]

[33] Exchange Act Release No. 9135, p.11 of Consent Decree (emphasis added)

[34] Ibid 33 p.7

[35] Ibid 33, p.8

[36] Ibid 33, p.9 (emphasis added)

[37] Lonegan II v. State of New Jersey, 819 A.2d 395 (2003) 176 N.J. 2

[38] State of New Jersey, New Jersey Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2005, p.20

[39] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Budget in Brief, Fiscal Year 2005, p.29

[40] Lonegan I v. State of New Jersey,174 N.J. 435, 809 A.2d 91 at 106

[41] Ibid 40 at 106

[42] Lonegan v. State of New Jersey, 176 N.J. 2, 19 (2003) at 406

[43] Lance v. McGreevey, 180 N.J. 590 (2004) at 861

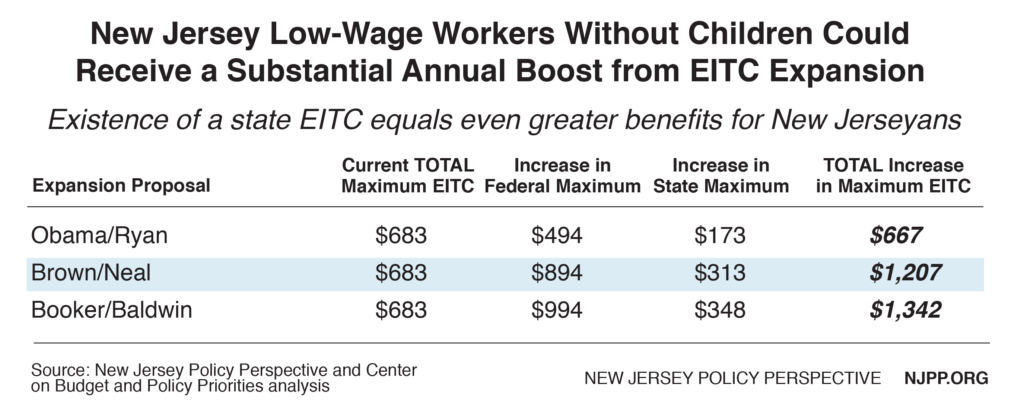

Thankfully, national leaders from both political parties agree that these workers shouldn’t be taxed into economic hardship, and they have plans to address it. President Obama and House Speaker Paul Ryan have put forth nearly identical proposals that would start a course correction by lowering the eligibility age for childless workers’ EITC to 21 from 25, and raising the maximum federal credit to roughly $1,000 from $506. This plan would help approximately 343,000 New Jersey workers, including 101,000 workers between the ages of 21 and 24 who would be eligible for the credit for the first time.[3]

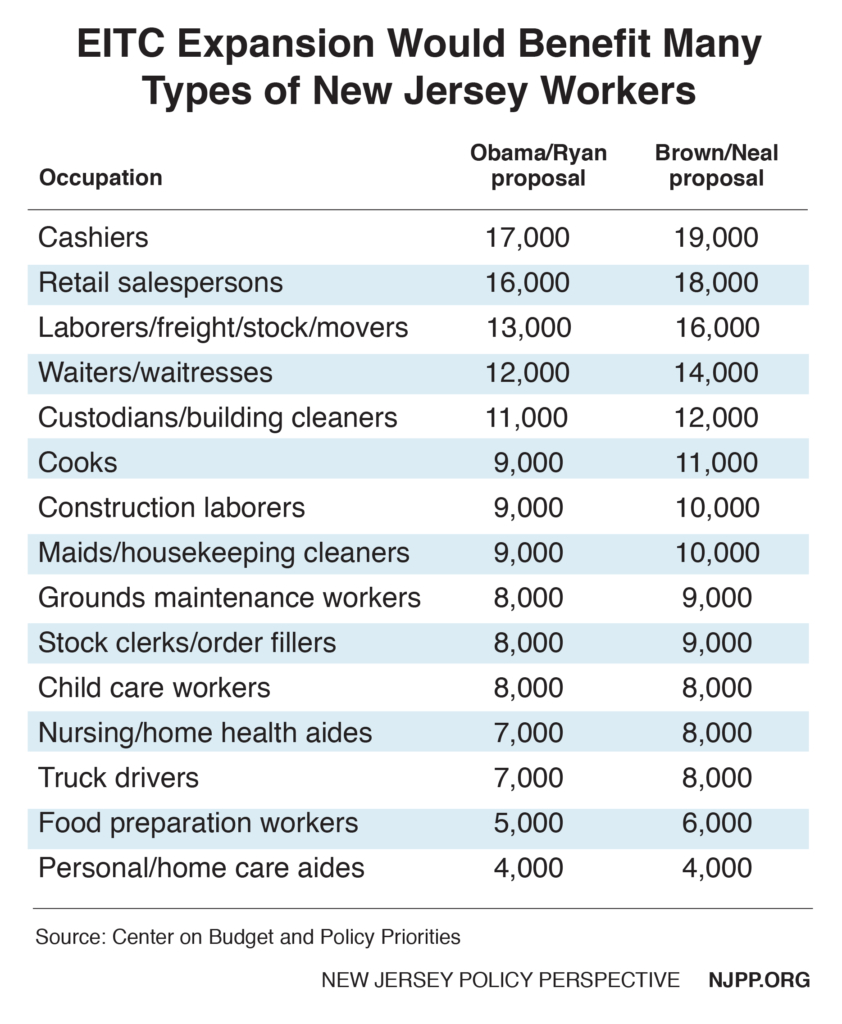

Thankfully, national leaders from both political parties agree that these workers shouldn’t be taxed into economic hardship, and they have plans to address it. President Obama and House Speaker Paul Ryan have put forth nearly identical proposals that would start a course correction by lowering the eligibility age for childless workers’ EITC to 21 from 25, and raising the maximum federal credit to roughly $1,000 from $506. This plan would help approximately 343,000 New Jersey workers, including 101,000 workers between the ages of 21 and 24 who would be eligible for the credit for the first time.[3] In New Jersey alone, thousands of workers across different ethnic groups and vocations would benefit from an EITC expansion to childless workers.

In New Jersey alone, thousands of workers across different ethnic groups and vocations would benefit from an EITC expansion to childless workers.

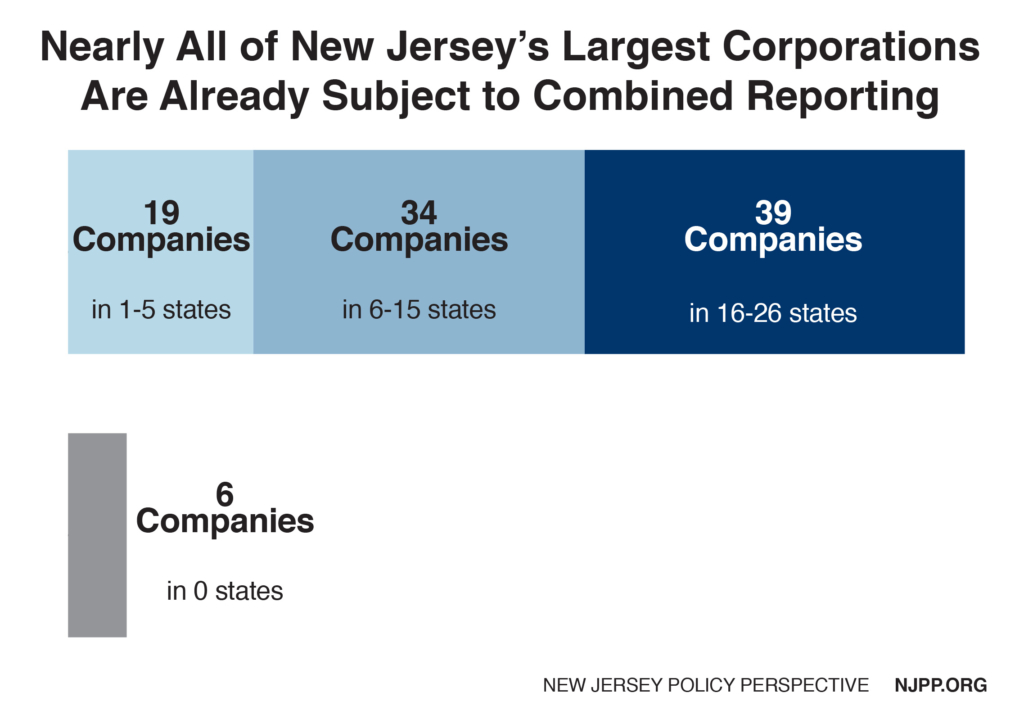

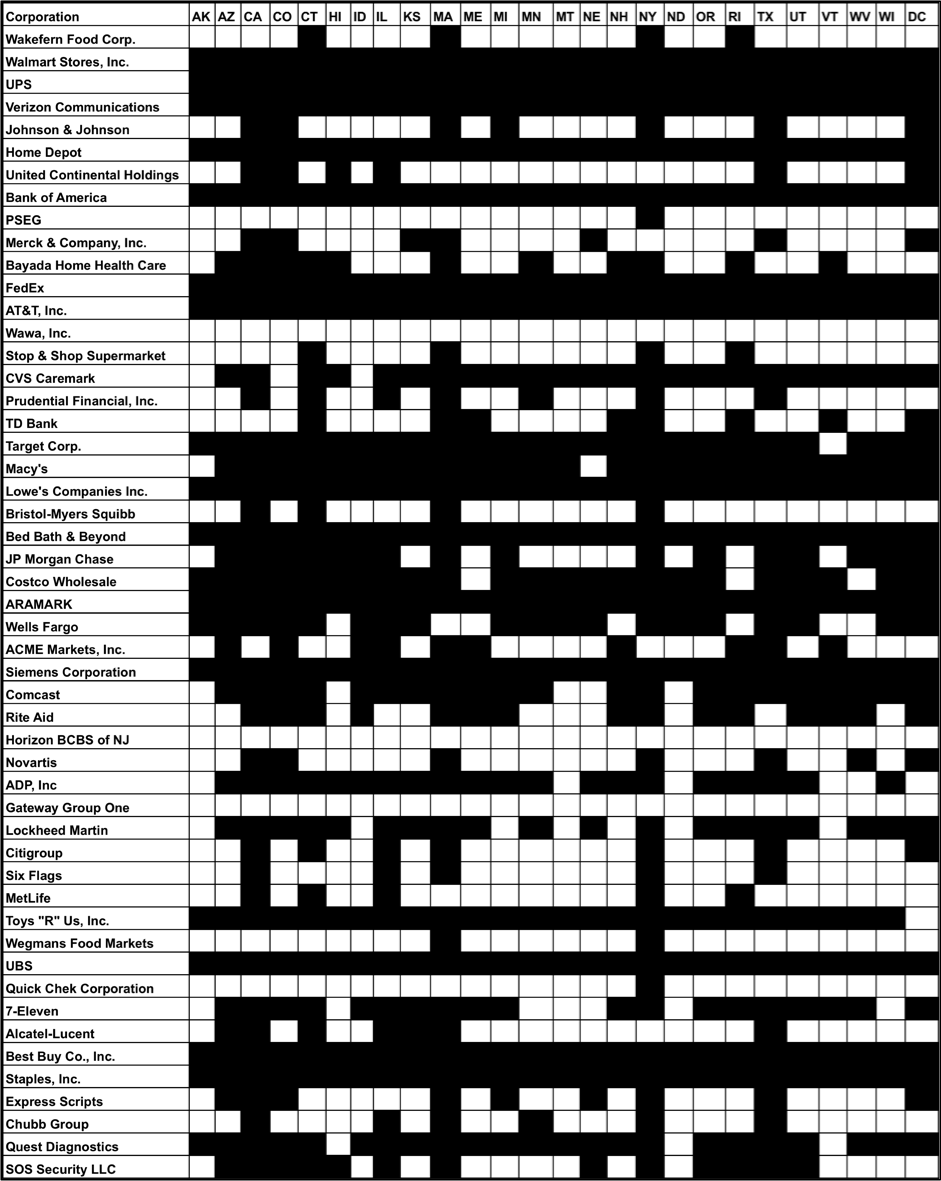

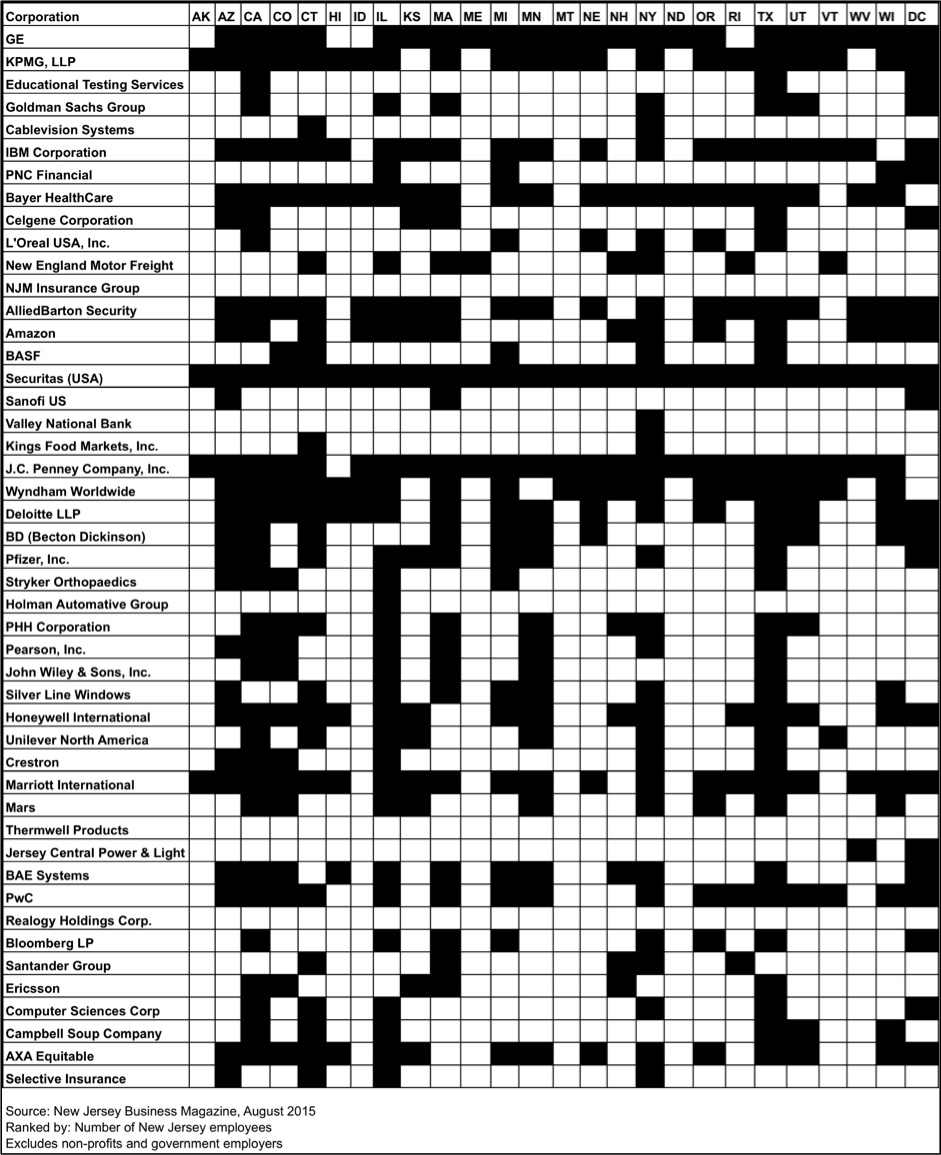

Most large corporations consist of a parent entity and its subsidiaries. Combined reporting treats the parent company and subsidiaries of multistate corporations as one entity for state corporate income tax purposes. Their nationwide profits are added together and the state then taxes the appropriate share of the combined income. With recent enactment in Rhode Island and Connecticut, 25 out of the 45 states that have some form of corporate income taxation, plus the District of Columbia, now mandate combined reporting.

Most large corporations consist of a parent entity and its subsidiaries. Combined reporting treats the parent company and subsidiaries of multistate corporations as one entity for state corporate income tax purposes. Their nationwide profits are added together and the state then taxes the appropriate share of the combined income. With recent enactment in Rhode Island and Connecticut, 25 out of the 45 states that have some form of corporate income taxation, plus the District of Columbia, now mandate combined reporting.