To read a PDF of this report, click here

By Erika J. Nava, Policy Analyst, and Gordon MacInnes, President

It’s time for New Jersey to build on steps taken in 2013 to help undocumented students in the state have a better shot at a college education.

New Jersey took an important step to boost educational and economic opportunities for undocumented students living in the state by allowing them – if they met certain requirements – to pay in-state tuition rates instead of much higher out-of-state rates at public colleges and universities. This has clearly helped more undocumented New Jerseyans pursue a higher education, which will put them – and New Jersey – on a path towards greater economic opportunity.

More of these students would benefit from college if New Jersey enabled them to apply for state financial aid and if public universities engaged in more outreach activities. Without these steps, too many striving students will be left behind and the stated intent of the Tuition Equality Act – to help these students succeed and contribute to society – won’t be fully realized.

There are three compelling reasons for the legislature and governor to extend New Jersey’s financial aid programs to undocumented students eligible for admission to the state’s public colleges and universities.

- An eligible student is most likely to come from a working-poor family with insufficient income to afford in-state rates. Unlike their citizen peers from low-income families, these students are not eligible for federal Pell Grants or student loans, a critical source of funding to meet the escalating costs of college. Today, neither can they turn to New Jersey’s Tuition Aid Grants, the Educational Opportunity Fund or CLASS student loans. Given that the average undocumented family scrapes by on an estimated $34,500[1] a year that is eaten up by housing, transportation, food and other basic needs, there is no room for savings. Meanwhile, just the tuition and fees at four-year public institutions average $13,200.[2] It is no surprise that after two academic years only 577 tuition equity students enrolled in the most recent semester.

- New Jersey taxpayers have already invested significantly in the primary education of eligible students. To deny them the same opportunities extended to their citizen classmates from low-income families is to waste most of that investment. Consider that a 3-year-old arriving with her undocumented parents in one of the state’s 31 former Abbott districts could have received two years of preschool and 13 years of a K-12 education at a total cost approaching $300,000. Just the three years of high school required to be eligible for in-state tuition could easily cost taxpayers in the range of $60,000-$75,000.

- Given the likelihood that their families lives in poverty and that undocumented students grow up with a near-constant fear of deportation due to their legal status, students who are eligible for in-state tuition rates must exhibit qualities of persistence, enterprise and intelligence. Many of them hold down jobs to supplement the minimal contribution their parents can make. In short, they represent precisely the kinds of young New Jerseyans the state should be investing in.

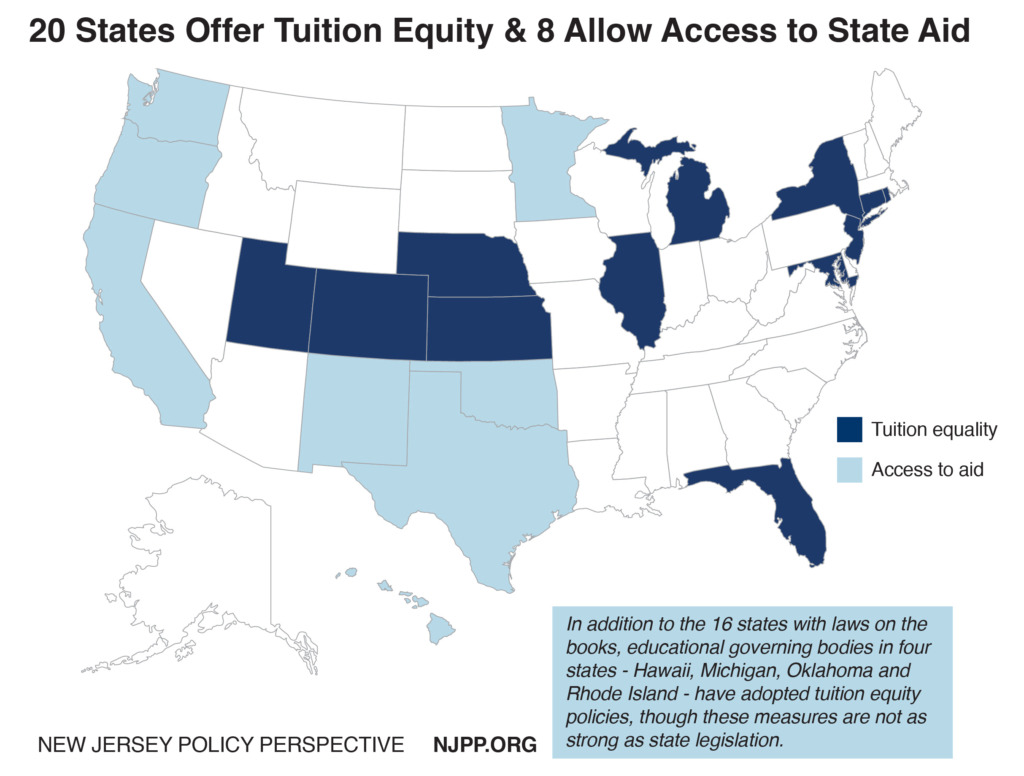

Currently, undocumented students who attend a New Jersey high school for at least three years and graduate can pay in-state tuition rates at the state’s public colleges and universities. New Jersey is one of 20 states with this policy,[3] which cuts the cost of college about in half for undocumented students. For example, in-state tuition was $7,824 per semester at New Jersey Institute of Technology this past academic year, compared to an out-of-state rate of $14,644.[4]

Allowing undocumented students to apply for state financial aid like Tuition Aid Grants (TAG), as eight other states do,[5] would make a college education a real possibility for more of these students, boosting their prospects for a prosperous future.

More Students Are Benefiting from Tuition Equity, But The Overall Numbers Remain Relatively Small

In the third and fourth semesters of the new law, the number of enrolled tuition equity students continued to climb, to 407 in Spring 2015 and 577 in Fall 2015 from 138 students in the Spring 2014 semester. Even though enrollment has increased, 577 students – out of more than 145,000 total undergraduate enrollees – is still a tiny sliver (less than one half of 1 percent, in fact).[6]

In the third and fourth semesters of the new law, the number of enrolled tuition equity students continued to climb, to 407 in Spring 2015 and 577 in Fall 2015 from 138 students in the Spring 2014 semester. Even though enrollment has increased, 577 students – out of more than 145,000 total undergraduate enrollees – is still a tiny sliver (less than one half of 1 percent, in fact).[6]

Over four semesters, 491 new students – defined as those who had never enrolled at the institution before, including transfer and first-time students – have now enrolled under the law, according to data obtained through NJPP’s ongoing survey of New Jersey’s 11 four-year public colleges[7] and universities.[8]

In the Fall 2015 semester, the most recent semester for which we have data, Rutgers University, which enrolls one third of all senior institution undergrads in New Jersey, attracted half of all tuition equity students. NJIT and Montclair State, William Paterson and Kean Universities each enrolled 50 or slightly more; Rowan, Ramapo and Stockton Universities were in single digits. Location and brand explain a lot of these variances, but effort and outreach do too.

It’s important to note that some documented students may also be included in the numbers. Documented U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents, for example, are also eligible for in-state tuition rates if they meet the law’s other requirements and submit the required affidavit. This is because the 1996 federal Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act dictates that no public benefit can be offered to undocumented residents without it also being extended to documented residents who have to meet the same requirements. For example, a documented student who met the New Jersey public school and graduation requirements but then moved to another state and now wants to attend a New Jersey public college or university, now qualifies for in-state tuition. It’s unclear just how many of these students exist, and it’s worth noting that these students enjoy an important advantage, which is that they quality for federal aid programs including Pell Grants.

Undocumented Students Face Huge Financial Barriers

We asked admissions officials why tuition equity students who accepted offers of enrollment failed to enroll. Their answers were not always definite, as admissions counselors frequently do not hear back from admitted but unenrolled students. That said, it is clear to some administrators that cost is a major reason. As Rutgers University’s Vice President of Enrollment concluded: “Most of these young people, even with an allowance for in-state tuition, cannot afford to attend public universities such as Rutgers.”[9]

The number one reason undocumented immigrants do not attend college is affordability.[10] Like other working-class students, undocumented students face daunting financial barriers. However, their legal status creates additional roadblocks, the largest of which – in most states – is a lack of access to financial aid. But even in states that allow undocumented students to receive state-based aid, these students remain shut out from federal Pell grants, the largest aid program for low-income students.

In addition, undocumented students usually don’t have credit lines and their undocumented parents can’t co-sign for private loans, even if their incomes are steady and large enough to qualify.[11]

Some tuition equity students now benefit from the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, which allows undocumented youth who came to the U.S. as children to obtain a Social Security number and work permit, driver’s licenses and protection from deportation, all of which enhance their opportunity to consider college. This enables them to find better-paying jobs, which in turn can help them pay for their education. Before DACA, undocumented youth were more reliant on low-wage “under-the-table” jobs, and as a result putting together money for college took longer. But even with DACA, the lack of access to financial aid creates an untenable barrier for too many students.

This is the case with Money Othatz, a recent graduate of Dover High School, whose future is in limbo due to state and federal immigration policies. Emmanuel is an honor student who was accepted to about 15 universities, about half of which were in New Jersey. Many in Emmanuel’s place would be excited to have more than one university to pick from. However, even with merit-based scholarships, Emmanuel couldn’t commit to a four-year public university because scholarships don’t cover total costs and he does not qualify for federal or state aid. “Now I know why many students in my situation give up,” he says. “You see a very narrow opening to continuing your studies; sometimes an impossible opening if your dream requires an advanced degree, like being a lawyer.”

Moreover, the experience of other states echoes what we’ve seen thus far in New Jersey. One study of undocumented students that enter the City University of New York shows that the biggest difference between undocumented students and documented students is the financial aid received.[12] For example, 67 percent of permanent residents and 60 percent of U.S. citizens received tuition assistance from New York State, yet no undocumented students did. As a result, undocumented students in bachelor’s degree programs were far less likely than their documented peers to complete their degree in four or five years – if at all.

And when California passed in-state tuition without financial aid, many students chose community colleges, because of their substantially lower costs, despite being accepted to the state’s four-year institutions.[13]

But that changed after the Golden State passed legislation in 2011 allowing undocumented students to receive state financial aid if they qualified for in-state tuition. Since then, California’s university system has seen a big increase in undocumented student enrollment.[14] In other words, if you build it, they will come: more students are able to pursue a college degree if they have the opportunity to apply for state financial aid.

New Jersey has already invested tens of millions of dollars to educate its undocumented students (precise costs cannot be calculated since public schools cannot request immigration status). It makes no sense to let that investment go to waste by keeping a four-year college education – and the higher earnings and brighter job prospects that a degree brings – out of reach. New Jersey would benefit from more of these kids attending college and giving back to the state they have come to call home.

Outreach Matters: Universities Should Do More to Spread the Word

Only four of New Jersey’s 11 four-year public colleges and universities even mention tuition equity in admissions information sessions, and only one – Rutgers University – conducts outreach specifically geared towards these students. Thus, it is no surprise that Rutgers has accounted for half of the enrolled students each semester since tuition equity was launched.

Outreach and recruitment toward this population is important to demonstrate to students that a college or university is inclusive and willing to help them navigate confusing terrain. New Jersey’s institutions should help these students manage required forms by designating a contact person for questions and advice, providing information about available financial assistance like private grants and publicizing employment opportunities for those with DACA status.[15]

Rutgers is the leader in the outreach department, having conducted several major informational sessions for undocumented students, each attended by hundreds of prospective students.

The Cost is Minimal Compared to the Economic Benefits

Extending state financial aid to New Jersey’s undocumented students would entail modest costs while delivering a huge benefit to the state’s economy in the long run.

Tuition equity students currently make up less than 1 percent of total enrolled students at New Jersey’s public four-year institutions. If financial aid were to become available, it would almost certainly increase the number of students seeking a four-year college education. But even if their numbers doubled, and if every student obtained financial aid, they would represent less than one percent of all students receiving Tuition Aid Grants, New Jersey’s largest aid program for economically stressed students. In Texas, for example, a much bigger state with more undocumented students, those getting aid represent about 1 percent of total students.

New Jersey is finding out, like other states, that in-state rates alone are not enough to help these talented and willing people have a shot to build a better future in the state they call home. Allowing them to fulfill their potential in a state that has already invested in them is a common-sense investment.

Endnotes

[1] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Undocumented Immigrants’ State and Local Tax Contributions, February 2016.

[2] NJPP analysis based on the average tuition and fees at all 11 schools, not including room and board.

[3] National Immigration Law Center, Laws & Policies Improving Access to Higher Education for Immigrants, May 2016.

[4] New Jersey Institute of Technology Office of the Bursar, 2014-2015 Undergraduate Tuition & Fees.

[5] Ibid 3

[6] New Jersey Department of Higher Education, Preliminary Enrollment in N.J. Colleges and Universities, March 2016.

[7] It is no surprise that Thomas Edison State University has not admitted or enrolled any tuition equity students, because it is considered an adult institution and most beneficiaries of the in-state tuition law are around the average college age.

[8] Our analysis does not include two-year county colleges, even though most undocumented students enroll in community colleges due to their lower costs. We omitted these institutions because most of New Jersey’s community colleges already had a de facto policy of charging in-county rates to all students, regardless of status. With the exception of Morris and Warren County Colleges, they employed a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” admissions policy when it came to undocumented students.

[9] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Tuition Equality Act is a Half-Measure Without Access to Financial Aid, April 2015.

[10] New Directions for Community Colleges, Undocumented Students at the Community College: Creating Institutional Capacity, Winter 2015.

[11] Institute for Education and Social Policy, Undocumented College Students In the United States: In-State Tuition Not Enough to Ensure Four-Year Degree Completion, March 2013.

[12] The study used the name Urban College System in New York (UCSNY) to refer to CUNY, as a large urban university system educating more than 480,000 students in over 20 colleges and institutions.

[13] Latino Studies, Undocumented Students’ Access to College: The American Dream Denied, 2007.

[14] Capital Public Radio, Charts: AB 540 University of California and the California Dream Act, October 2015.

[15] Ibid 11