Household incomes are stagnant. Poverty, true poverty and deep poverty persist and remain far higher than prior to the Great Recession. Income inequality is on the rise. Nearly half of young adults aren’t striking out on their own, opting to live at home instead. And nearly all of these metrics are worse for people of color and women.

In other words, the kitchen-table economics of working- and middle-class New Jerseyans across the state – as brought to light in the 2015 American Community Survey data released this week – are yet more evidence that New Jersey’s near-decade experiment with trickle-down economics hasn’t worked. The prosperity has not, in fact, trickled down.

This bleak picture in New Jersey is not new, but each year it stands in starker and starker contrast to national trends. In 2015, American median household incomes grew by more than 5 percent and the share of people in poverty dropped by more than 1 percentage point.

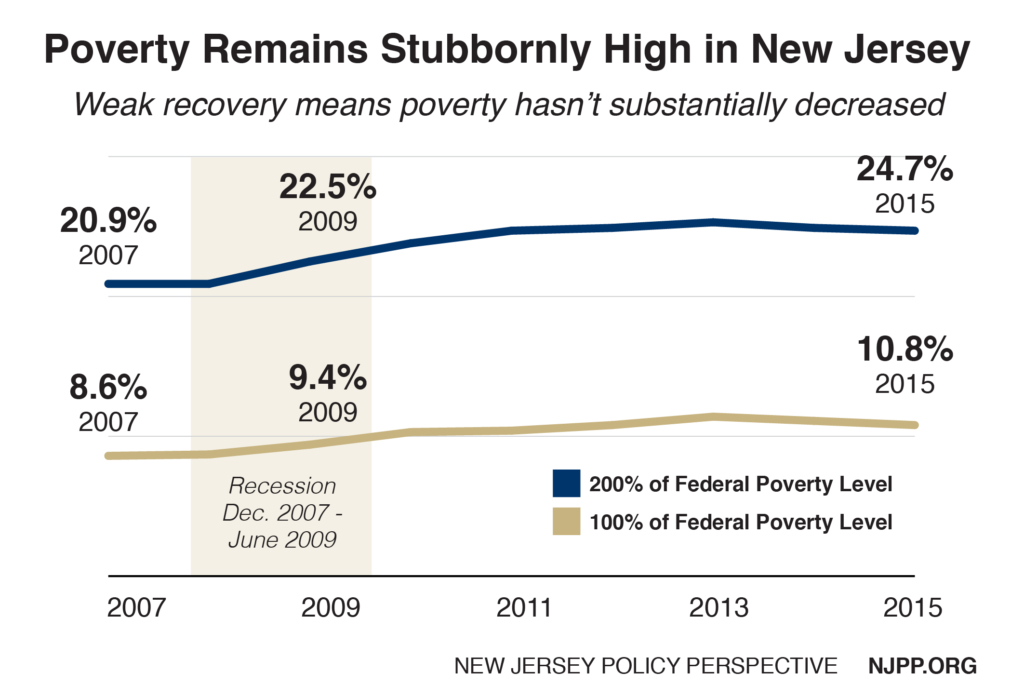

Back home, the Garden State ranked last among every state in household income growth during 2015, seeing just a 0.3 percent rise in median household income, which inched up to $72,222. And poverty remained stubbornly high, with a slight drop in people living under 100 percent of the federal poverty level (which, at $20,160 for a family of three, is clearly an inadequate measure of true poverty in New Jersey), a slight increase in people living in deep poverty (defined as 50 percent of the federal poverty level) and a slight dip in people living below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, a more accurate measure of true poverty in this high-cost state. (All of these year-to-year changes were statistically insignificant, as they were within the Census’ margin of error.)

In other words, one in four New Jerseyans is still struggling to get by, while one in ten lives below the official and inadequate poverty line and one in twenty lives in absolutely desperate economic circumstances.

Child poverty also dropped slightly – to 15.6 percent from 15.9 percent – but the change was statistically insignificant, falling within the margin of error. Child poverty is still 34 percent higher than it was before the Great Recession, when it was 11.6 percent in 2007.

While poverty has fallen slightly across most groups, New Jerseyans of color continue to experience significantly higher levels of poverty than others. Poverty among African Americans fell from 19.7 percent to 18.6 percent; and among Hispanics and Latinos of any race poverty dropped from 21.2 percent to 20.2 percent. These rates are significantly higher than poverty among whites, which dropped from 8.5 percent to 8.2 percent. Among Asians, poverty rose from 6.8 percent to 7.1 percent. For the category of “Some Other Race” poverty dropped to 20.2 percent from 21.2 percent, and among individuals of “Two or More Races” poverty increased to 17.7 percent from 14.3 percent.

Poverty among women also remains higher than poverty among men. For women, the rate of poverty dropped from 12.2 percent to 11.7 percent. Among men, the poverty rate remained largely unchanged, dipping slightly from 10 percent to 9.8 percent. For both groups, the poverty rate is higher than it was in 2007, when it was 9.7 percent for women and 7.3 percent for men.

At the same time most families are struggling, those at the very top continue to do quite well, thank you very much. In fact, New Jersey was one of only eight states that saw income inequality increase from 2014 to 2015, and it is now at its highest level ever.

And while New Jersey ranks near the bottom on a number of economic statistics, there is one in particular where we are second to none – nearly half (46.9 percent) of young adults (18-34 year olds) live at home with their parents, more than any other state by far (Connecticut comes in second at 41.6 percent).

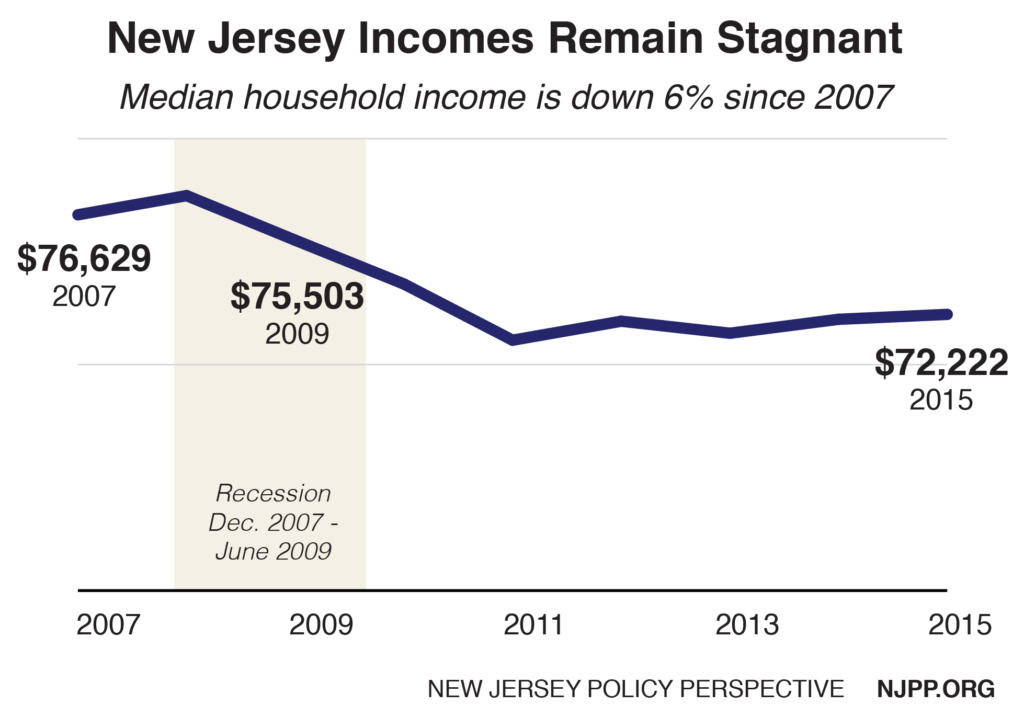

For those who have been paying attention, this information – while distressing – shouldn’t be surprising. New Jersey has had one of the nation’s weakest recoveries out of the Great Recession; in many cases it has not yet returned to pre-recession levels. When making the necessary adjustments for inflation, for example, median household income is still about $4,400 lower than it was in 2007, when it sat at $76,629.

Even though New Jersey has enjoyed a drop in the annual unemployment rate, which has gone from 10.9 percent at its peak in 2011 to 6.6 percent in 2015, it is still higher than it was before the recession (it was 5.9 percent in 2007). Additionally, when unemployment goes down, it is sensible to expect poverty to go down as well, but that hasn’t been the case for New Jersey. The poverty rate remains stubbornly high at 10.8 percent, up from 8.6 percent in 2007. And true poverty – incomes less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level – at 24.7 percent in 2015, also remains significantly higher than in 2007, when it was 20.9 percent.

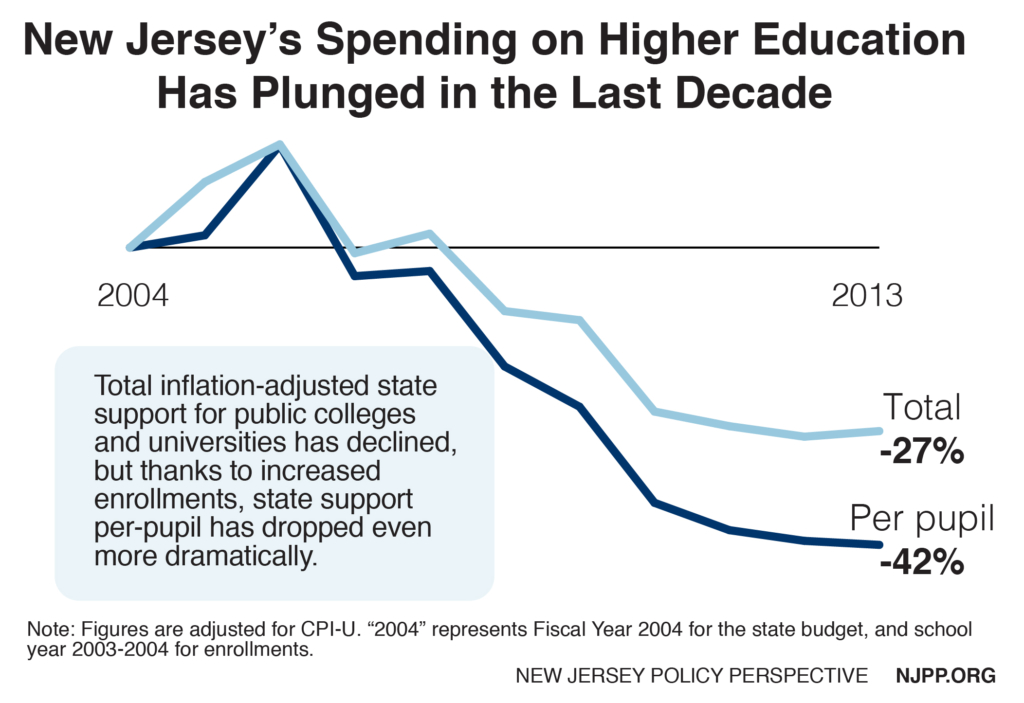

New Jersey still has a very long way to go before we recover all that was lost during the Great Recession, as our recovery continues to lag significantly behind the rest of our region and the nation. In order to get back on the right track, policymakers must find ways to invest in the state’s assets, including our workers and families, so that our economy can grow and our state can be strong and resilient.