Introduction

After the murder of George Floyd, millions of people across all 50 states protested against police brutality and racial injustice.[i] Floyd’s death followed a long history of police violence against Black people and was heavily covered in the national media along with the police murders of Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, and Tony McDade.

Models of public safety that center police are premised on punishment and have far-reaching consequences, especially for young Black men.[ii] Beyond police brutality, which is the most life-threatening and visible failure of the current criminal justice system, frequent police interactions are linked to adverse mental health outcomes, including anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder.[iii] These outcomes are exacerbated in communities of color. Due in part to a history of racial profiling, Black men in particular experience high levels of depression and anxiety over the very possibility of encounters with police.[iv] Taken together, these harms have prompted a widespread examination of the actions of law enforcement and a close evaluation of the role that budgets, which are a measure of municipalities’ values and priorities, play in funding ineffective and deadly practices that disproportionately target Black residents.

This report examines how New Jersey can create a safer, healthier, and more equitable state for all by reimagining public safety and exploring crisis response models that are not led by police. The first sections of this report provide important historical context on how policing evolved into the system seen today. In short, the racialized history of criminal justice policies and practices, such as “broken windows” policing and the War on Drugs, encouraged aggressive policing tactics, skyrocketing incarceration rates, and larger police budgets.

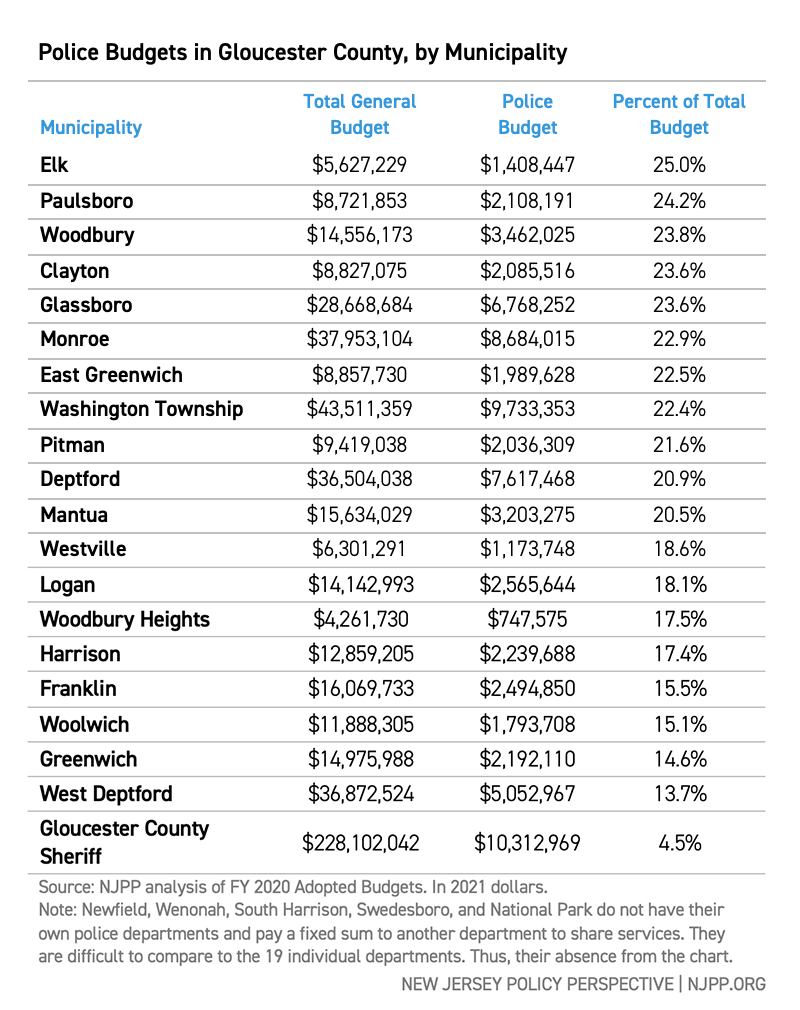

Next, this report examines police budgets in two distinct geographical areas — the City of Elizabeth and Gloucester County — to highlight how, regardless of the geographic region, local governments invest vast resources on law enforcement while essential health and human service programs are underfunded. Elizabeth is a diverse, vibrant city in Northern New Jersey. Its police budget makes up 19 percent of the total municipal budget and has increased by an average of $1.8 million each year since 2018. In comparison, Gloucester County is a more rural area in Southern New Jersey that, while not lacking in racial and ethnic diversity, has a more segregated population than Elizabeth.[v] Across the county, local police budgets vary from about 14 percent to 25 percent of the total municipal budget, with an average of 20 percent. In total, local governments in Gloucester County appropriated over $77 million to police departments in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 alone.[vi] The report then puts police budgets in context by comparing them to local investments in health and human service programs, which promote public safety more broadly by addressing the structural root causes of crime.

Finally, this report proposes alternative models to public safety that are centered on harm reduction and a broader vision for a safer and more just New Jersey. This includes a range of public health policies designed to minimize negative social, emotional, and physical outcomes for all residents. The policy recommendations included in this report were crafted with input from residents directly harmed by police violence, as well as faith and community leaders.

Policing in the United States: A Primer

Policing and race have always intersected in the United States. From the horrors of slavery, to the terror of Jim Crow, to the modern era of mass incarceration, the U.S. has systematically used public policy and the criminal legal system to disempower and subjugate Black residents. Policies that define criminal behavior or “crime” have changed over the years and, as demonstrated below, are often racialized and used to maintain social control rather than to promote public safety. Whether expressly or implicitly, police departments are the enforcement arm of these public policies. The following section examines the link between racism and law enforcement and the role policing plays in creating and maintaining racial inequities.

Slave Patrols (1700s–1800s)

Most modern police departments can trace their roots directly to slave patrols, which were organized, government-sanctioned groups of armed men who monitored and, by use of violence, regulated the activity of people who were enslaved. Indeed, historians describe slave patrols as the first publicly funded police departments in the South.[vii]

Slave patrols were first established in the early 1700s to enforce slave codes, or laws that defined enslaved people as property.[viii] The patrols served three main functions: chase down those who had escaped, “provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts,” and punish any enslaved worker who was alleged to have violated the rules of a plantation.[ix]

Historical evidence suggests the beating and terrorizing of enslaved people by patrollers was officially justified as a civic duty.[x] In many states, serving on these patrols was required of all able-bodied white men.[xi]

After the end of the Civil War, slave patrols evolved into police departments, carrying over many aspects of the patrol, including the systematic surveillance of Black communities.[xii] In the years that followed slavery, the primary role of police departments was to enforce Black Codes, an extension of the slave codes, and Jim Crow segregation laws, both of which were designed to deny Black residents equal rights and maintain the de facto structure of slavery.[xiii]

The Great Migration and Segregation (1900s–1970s)

Due, in part, to the brutal enforcement of segregation laws in the South, millions of Black residents moved from Southern states to Northern states between 1916 and 1970, a population shift known as the Great Migration.[xiv] People who migrated, however, would come to find that segregation and systemic racial violence were also woven into the fabric of Northern states. Contrary to popular belief, segregation began in Northern abolitionist states with the country’s first racially separate railcar operating in 1838.[xv]

In Northern states, police departments did not develop as a response to crime but, rather, “disorder.”[xvi] Governments tasked police with the surveillance and control of disenfranchised people: poor workers, immigrants, and Black people.[xvii] Again, police were encouraged to use force against these disenfranchised communities, and police violence was commonplace in the early 1900s.[xviii]

At this time, police were required to enforce segregation and keep order by squashing any unrest, or perceived unrest, among Black communities. By the 1940s, police in Northern states had earned a reputation for protecting whites at the expense of the Black population.

“[Police] used ‘persuasion’ rather than firm action with white rioters, while against Negroes they used the ultimate in force: nightsticks, revolvers, riot guns, sub-machine guns, and deer guns.”

-Thurgood Marshall, describing the experience of protests that erupted in Detroit over police brutality and racial animus due to the increasing Black population, “The Gestapo in Detroit,” The Crisis, 1943

New Jersey, now known as one of the most progressive states in the nation, also played a role in the systemic subjugation of Black residents. Black New Jerseyans could not enjoy summers at the shore, lived in segregated neighborhoods, and were barred from most entertainment and social venues until the passage of federal civil rights legislation in 1965.[xix] De facto segregation and hostility towards Black people, however, continued.

In the summer of 1967, residents of Newark rebelled after witnessing white police officers brutally attack John Smith, a Black cab driver.[xx] While this instance of racial violence was a breaking point for many, the rebellion emerged also in response to rising tensions over “urban renewal” policies that sought to raze and redevelop neighborhoods without input from Black residents as well as and the ongoing abuse and killing of Black people by police.[xxi] After several days, 700 people were injured and 26 died, most of whom were Black.[xxii]

The rebellion lasted less than a week, but its legacy still looms large today, where the relationship between police and the general public remains strained by decades of violence.

“There are still some emotional trauma and other things we haven’t recovered from and social conditions that led to the rebellion itself. And it hasn’t been fully addressed.”

-Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, in response to whether or not the city of Newark had recovered from the 1967 riots, The New York Times, 2017

The War on Drugs and Mass Incarceration (1970s–2000s)

The Civil Rights movement brought inequities faced by Black and brown people to the forefront of public consciousness and won major legislative battles in the 1960s, namely the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, these wins did not prevent policymaking that criminalized and otherwise harmed Black and brown communities. The War on Drugs, 1990s-era crime bills, and the expansion of police powers in recent decades have arguably become an extension of Jim Crow-era policies criminalizing Black people.[xxiii]

The War on Drugs officially began in 1971 when President Richard Nixon introduced a wave of drug enforcement policies, declaring a “full-scale attack” on drug use.[xxiv] Since then, the drug war has led to a slew of federal, state, and local anti-drug policies that militarized police departments, expanded police powers, and ordered aggressive enforcement.[xxv] Nationwide, state and local police spending doubled from $131 per capita to $260 per capita between 1992 and 2008 to support the drug war, even as crime rates decreased.[xxvi] War on Drugs policing strategies also increased rates of police brutality with tactics like “stop and frisk” that encouraged the targeting of people of color.[xxvii]

The War on Drugs also resulted in mass incarceration. The number of people imprisoned in the U.S. increased roughly 6 to 8 percent per year from 1972 to 2000,[xxviii] drug arrests more than doubled between 1980 and 1989, and incarceration rates grew sharply in the 1980s even as violent crime rates fell.[xxix] In 2020, the 2.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S.[xxx] was seven times the number of people incarcerated in 1972.[xxxi]

Moreover, racial disparities in arrest and prosecution after 1972 produced high incarceration rates for Black people but not white people.[xxxii] From 1980 to 1990, Black people were imprisoned at a rate of 6.5 to 6.8 times that of white people,[xxxiii] despite white people both using and selling drugs at similar or higher rates.[xxxiv] By 2021, despite being 13 percent of the U.S. population,[xxxv] Black residents accounted for about 38 percent of all inmates.[xxxvi]

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or blacks, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin and then criminalizing them both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night in the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

-John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic policy advisor in a 1994 interview in response to what the drug war was “really about.”[xxxvii]

The Legacy Continues Today

Now that the history of policing in the United States has been outlined, we can better understand the present state of affairs. This section reviews current Black arrest and incarceration rates, deadly and non-deadly use of police force on Black residents, and how the system of policing, beyond the actions of individual officers, reinforces the rates of racial disparities and violence seen today.

Arrest and Incarceration

The U.S. is home to nearly 20 percent of the world’s prison population despite making up a mere four percent of the global population.[xxxviii] This high rate of incarceration does not indicate that U.S. residents are committing more crimes than their international peers; rather, it points to, in part, the overly harsh consequences of drug convictions. And despite an increased recognition from Democratic and Republican lawmakers alike that we cannot arrest ourselves out of drug use, enforcement of the drug war continues: in 2019 alone, approximately 1.6 million people in the U.S. were arrested, prosecuted, incarcerated, and placed under supervision and/or deported on a drug law violation.[xxxix]

Like the rest of the nation, New Jersey excessively enforces the drug war. Drug violations account for a large portion of arrests across the state, totaling approximately 21 percent of all arrests in 2019.[xl] Drug war arrests have also increased over the past 30 years. In 1986, New Jersey made 398 drug war arrests per 100,000 residents; in 2019, New Jersey made 626 drug war arrests per 100,000 residents — an increase of 57 percent.[xli] To learn more about drug war arrests and the associated social and economic costs, see NJPP’s report, A War on Us: How Much New Jersey Spends Enforcing the War on Drugs.

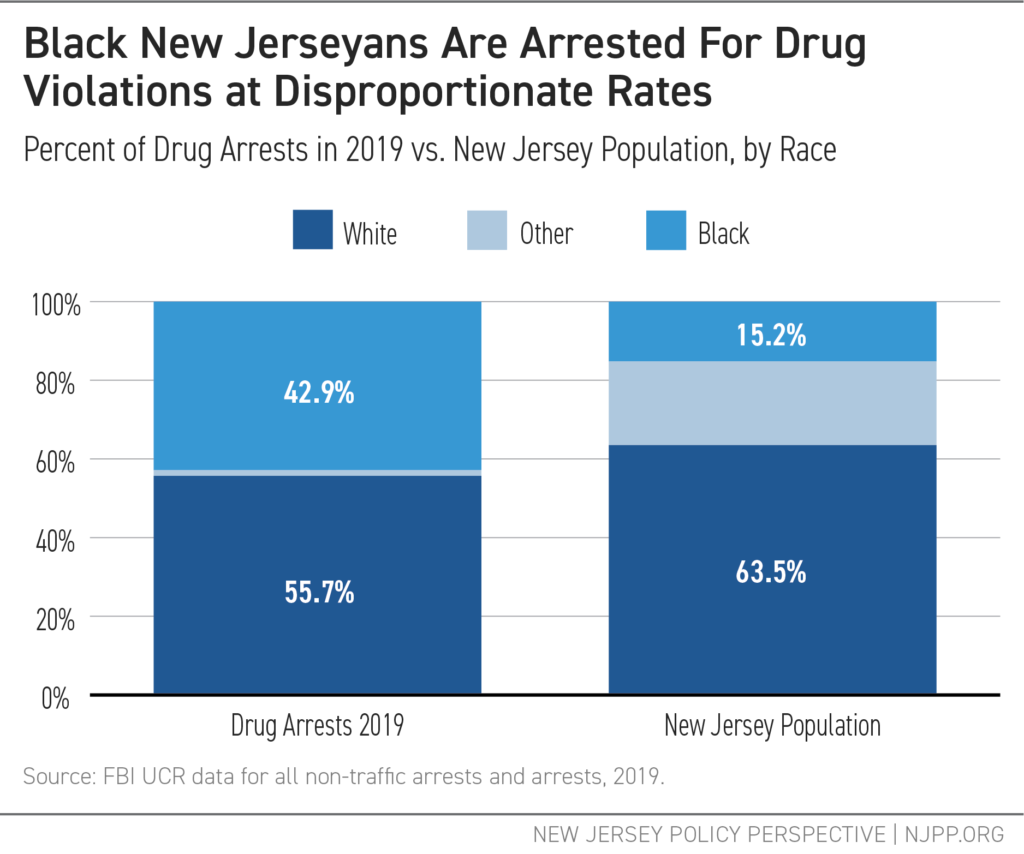

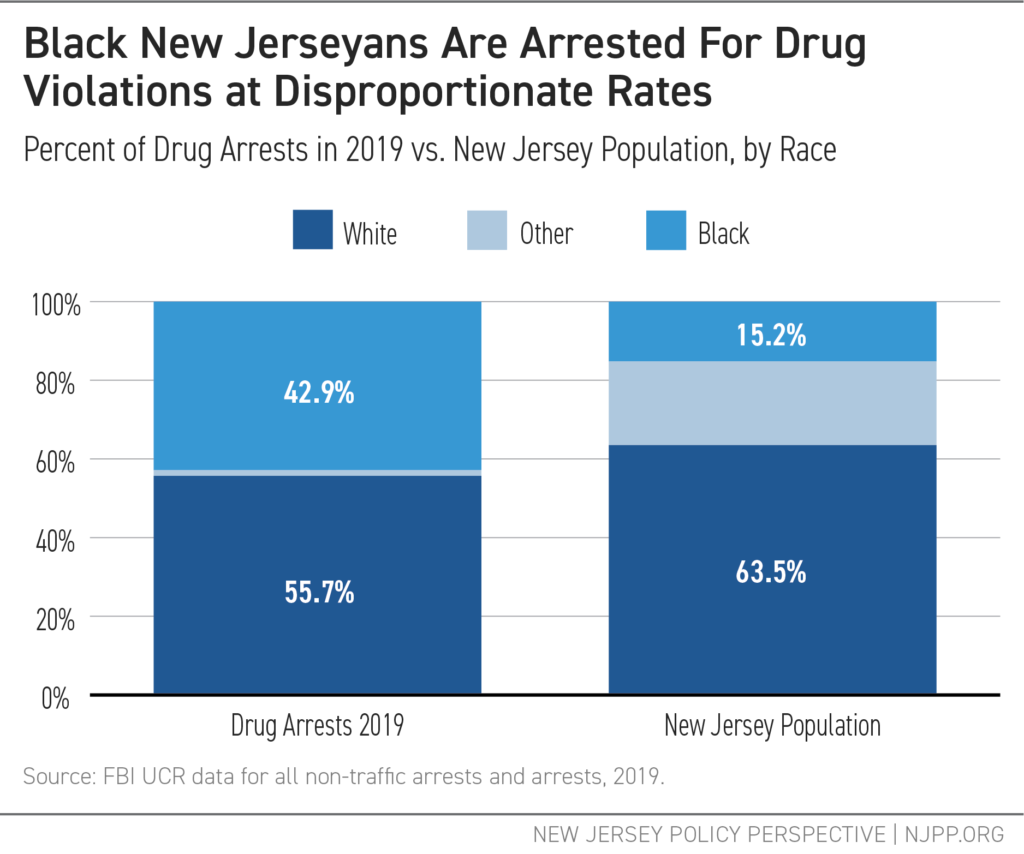

Of those arrested in 2019 in New Jersey for drug violations, 43 percent were Black[xlii] despite Black residents making up 15 percent of New Jersey’s population and national survey data showing that Black residents are no more likely to use or sell drugs than white residents.[xliii]

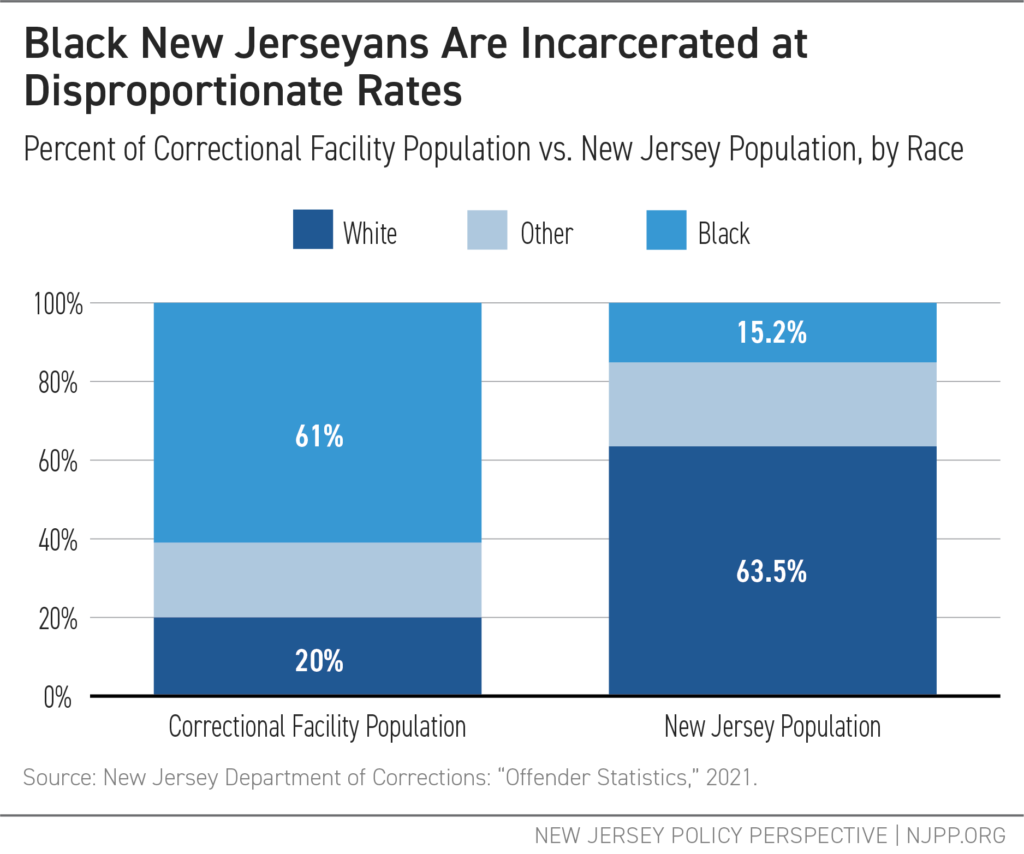

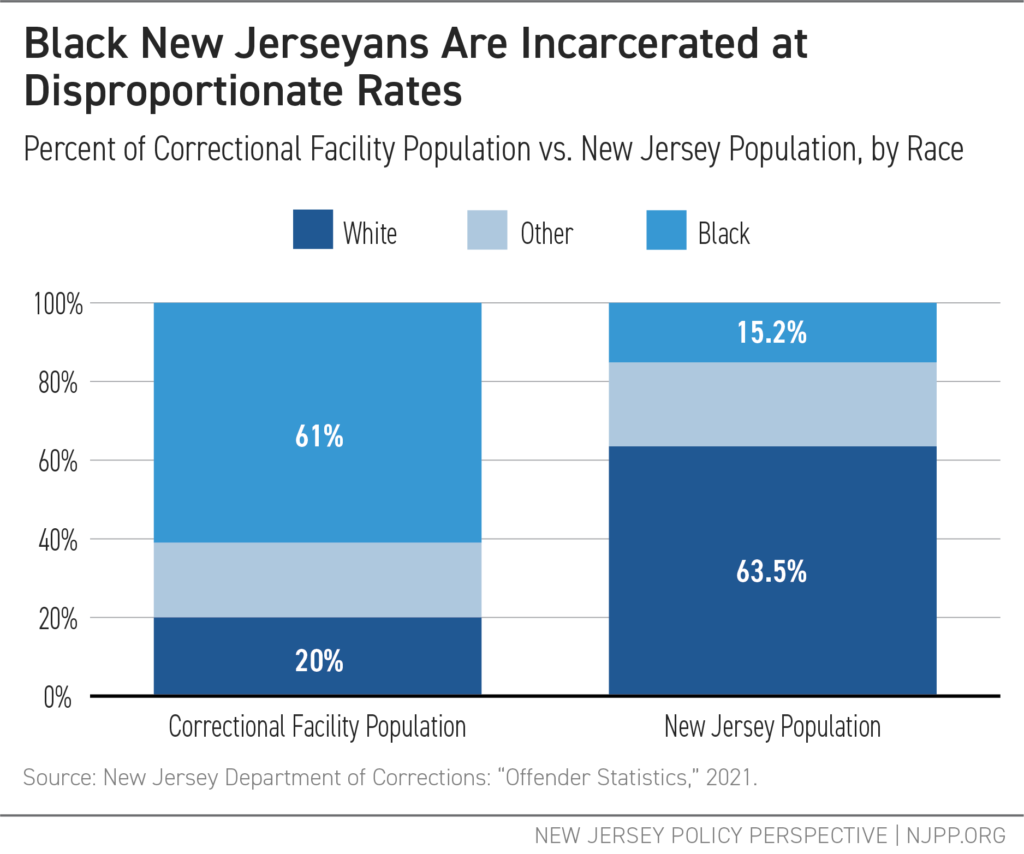

As of January 2021, Black New Jerseyans represent about 61 percent of the state’s correctional population,[xliv] even though they make up about 15 percent of the state population.[xlv] In contrast, white New Jerseyans account for 20 percent of the correction population, while representing 64 percent of the state population.[xlvi]

Use of Force

The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), arguably the largest social movement in recent U.S. history, brought increased attention to the murders of Black residents at the hands of the police and the role that the drug war plays in militarizing police forces, providing pretexts for police brutality.[xlvii]

What M4BL amplifies and what the data show are that police officers are more likely to use force on people of color than other populations. Broadly, use of force is contact that goes beyond what is usually required to make an arrest, including physical force such as striking, kicking, or tackling, and mechanical force, meaning the use of a weapon.[xlviii] Use of force is permitted under specific circumstances, such as in self-defense or in defense of another individual or group.[xlix] But here is where the problem lies: police officers do not receive uniform guidance about when situations necessitate use of force or how much force is appropriate.[l] This is true across the country and in the Garden State, making it difficult to determine police fault in excessive use of force incidents that result in injury or death.

As a result of this ambiguity, use of force has become routine and unchecked. In fact, the following data likely underestimate the magnitude of law enforcement violence given that comprehensive information on deaths, physical injuries, and frequency of encounters is limited and underreported.[li] Based on available New Jersey data, between October 2020 and February 2021, there have been over 5,000 documented incidents of police force across the state, or roughly 37 incidents per day.[lii] Of these incidents, at least 44 percent involved Black individuals, and 63.5 percent involved individuals that were documented as showing signs of being under the influence or having a mental illness.[liii]

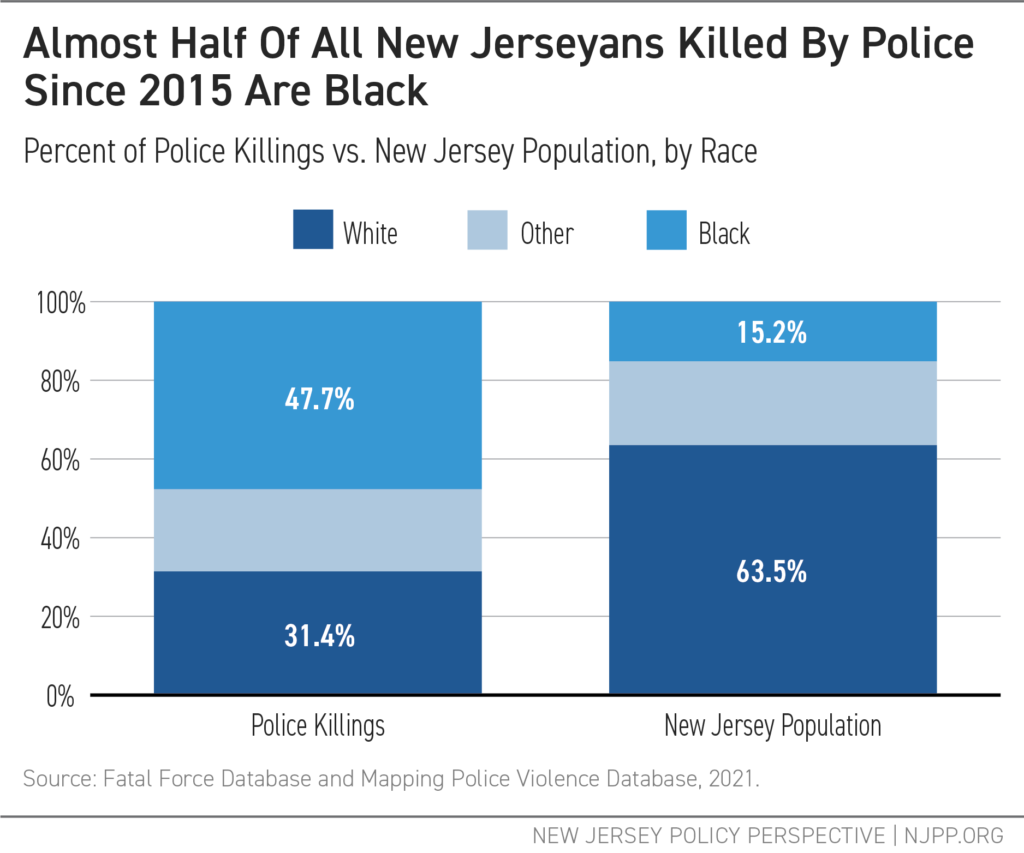

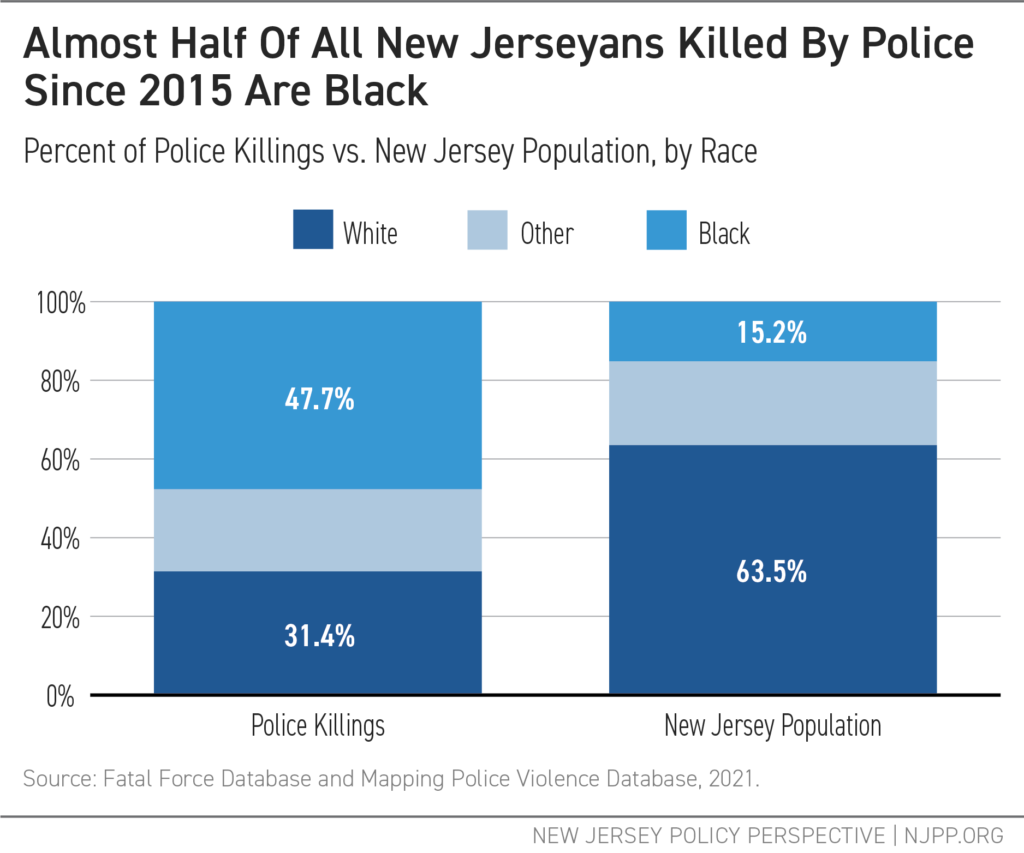

Far too often, police encounters result in not only injury but in death. Since 2015, police in the U.S. have shot and killed more than 5,000 people.[liv] Black people were killed at more than twice the rate of white people.[lv] In New Jersey, there have been 86 known deaths at the hands of police since 2015, with 14 of the people killed documented as showing symptoms of mental illness at the time of their death.[lvi] Almost half, 48 percent, of those killed were Black.[lvii] Consequently, New Jersey has one of the highest racial disparities among victims of police violence in the country: Black New Jerseyans are killed at a rate 8.3 times higher than white residents as compared to the national rate of three times higher.[lviii]

Civilians are not the only ones that can be harmed by the current system of policing. These same policies put police officers into situations for which they are not sufficiently trained or trained at all. For instance, police are often the first responders to calls for mental health emergencies, even though they are not trained mental health professionals. Because of this, there is increased risk of escalation and tragic results, contributing to the stigma, shame, fear, and criminalization of mental illness.[lix] Looking at training more broadly, police in New Jersey can work for 18 months before receiving even full basic police training.[lx]

Many instances of police violence stem from calls where an armed police response may not be the most appropriate. Roughly 58 percent of all police killings escalated from nonviolent situations, such as traffic stops, mental health checks, and domestic disputes.[lxi] One-fourth of all fatal police encounters involve individuals who have a mental illness, making those with mental illness more likely to be killed by a police officer.[lxii]

Despite the high stakes of police encounters, there is little oversight. Police oversight and accountability mechanisms are internal, with investigations often conducted by close colleagues, leaving room for bias. In other words, officers “police” themselves, and based on how police departments are structured historically, there is little guidance, a lack of external oversight, and few consequences.[lxiii] Of the 86 total killings by police in New Jersey between 2015 and 2021, only four officers have been charged with wrongdoing.[lxiv] Of those killed, 14 percent were documented as having no weapon whatsoever, and fewer than half were recorded as having a gun.[lxv]

Further, internal investigations rarely rule in favor of people who file civilian complaints, showing a lack of accountability for police violence more broadly. For example, from 2016 to 2018, the Elizabeth police department received 47 complaints accusing officers of excessive force, wrongful arrest, or other crimes.[lxvi] The internal investigations did not substantiate a single claim despite Elizabeth police officers’ using force at a rate that is 90 percent higher than other departments in New Jersey, including those in larger cities.[lxvii]

In sum, the history of policing in the United States shows a system conceived to surveil and control Black people, and one that has continued to do so well beyond the Civil Rights era of the 1960s. The result has been, at best, ineffectual policing for specific and delicate individual and communal crises and, at worst, active harm against the communities being policed, particularly communities of color. This system is fed by budgetary appropriations at multiple levels.

The Budget

Municipal budgets are much more than line items of revenues and expenses. Where investments are made — and where they are not — highlights what leaders value most. To better inform the ongoing and future debates about police budgets in New Jersey, this section analyzes the police budgets for the urban City of Elizabeth and the more rural Gloucester County. These case studies highlight the similarities and differences between two distinct areas, creating the opportunity to explore flexible recommendations that will not be one-size-fits-all. It also shows that investments in police departments are significant across the state, not just in densely populated areas. Please note that, from here on out, references to Gloucester County or Gloucester refer to the combined police budgets and departments of all of the municipalities within the county, as well as the Gloucester County Sheriff’s Office.

The budgetary analysis that follows shows both Gloucester County and Elizabeth spend more on policing than other vital municipal departments, such as health and human services. In Elizabeth, the police budget is over five times that of the Department of Health and Human Services. In Gloucester County, the combined county and municipal police budgets are more than two and a half times that of all the funding for health and human services departments in the county. Gloucester County allocates an average of 20 percent of their total municipal budgets to police, and Elizabeth allocates 19 percent. This is likely an underestimate, as it does not include pension payments, health benefits, and dollars that flow to police departments from other sources such as state and federal grant programs and other departments for police services.

Police Budgets 101

Police budgets in New Jersey vary from municipality to municipality, but they all have basic line-items. A New Jersey police budget typically includes funding for:

- Salaries and wages, including a set amount for anticipated overtime compensation

- Non-personnel costs including equipment maintenance, office supplies, travel, and training

The following are not included in police budgets, but account for significant expenses:

- Overtime compensation funded through grant programs[lxviii]

- Pension payments made by a municipality

- Health benefits and insurance costs paid by a municipality

- Most equipment upgrades or acquisitions, often found in capital improvements sections of municipal budgets

- Compensated absences, like unused paid time off that can be cashed out upon departure from the department, paid from a special reserve fund

- Additional funding and equipment to police departments from other sources, such as state and federal grant programs

City of Elizabeth

The City of Elizabeth is New Jersey’s fourth most populous municipality with more than 137,000 residents.[lxix] Roughly 20 percent of Elizabeth’s residents identify as Black, higher than the state’s 15 percent average.[lxx] The city also has almost double New Jersey’s poverty rate at nearly 18 percent, with a median household income of about $48,331 a year.[lxxi] As of 2021, the Elizabeth Police Department employs 365 law enforcement officers.[lxxii]

Police Appropriations

Elizabeth’s municipal police budget, which largely is allocated to base wages, is about $52 million, or about 19 percent of the city’s total budget, for Fiscal Year (FY) 2021.[lxxiii] The total budget includes $1.75 million for police overtime pay,[lxxiv] roughly $5,000 per officer.[lxxv] Over the last three years, Elizabeth’s police budget has increased by an average of 9.2 percent, or $1.8 million, each year.[lxxvi]

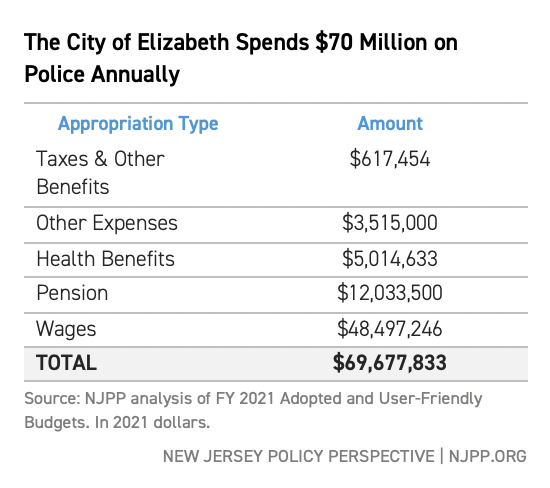

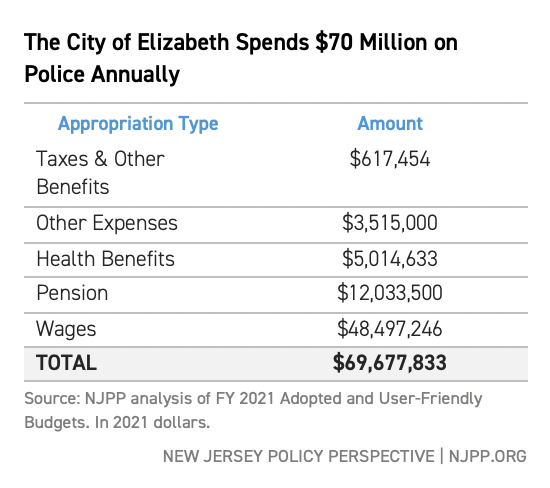

However, with pensions, health benefits, employment taxes, and other benefits included, Elizabeth’s police appropriations are about $69.7 million.[lxxvii] This is $507 per capita, and 25 percent of Elizabeth’s total budget.

In addition to pensions and health benefits, the municipality added additional funding for Elizabeth’s police department in FY 2021, such as:

- Compensated Absences: The city added $1.0 million to a fund that pays for compensated absences, or sick days, for all qualified municipal employees.[lxxviii] The current liability, or what the municipality potentially owes, for police officers is $9.8 million.[lxxix] Moreover, if a police officer takes no sick days for an entire year, they get a bonus of $1,500 with an additional $1,000 the following year if they can keep it up.[lxxx] These bonuses may have to be taken from elsewhere in the budget or bonded if a large number of officers qualify at the same time.

- Capital Improvements: Elizabeth also authorized $4.4 million in capital improvements amidst the global pandemic to upgrade the Elizabeth Police Department’s gym, showers, bathrooms, and conference room.[lxxxi] $200,000 of this will be taken from the capital improvement fund and the remaining $3.8 million will be taken on as debt. Capital improvement funding generally comes from a broader municipal fund to support large infrastructure projects that are expected to be paid for over multiple years. Examples include acquisition, construction, improvement and/or renovation of buildings, roads, utilities, or structures and acquisition or development of land.[lxxxii] Capital projects can also include acquisitions of major equipment, which is how many police departments receive funding for new technology.

Additional Revenue

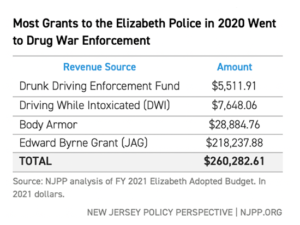

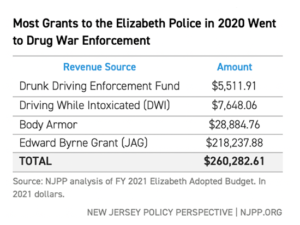

In addition to local revenue, New Jersey police departments receive funds from federal, state, and private grants. For example, Elizabeth received about $260,300 in state and federal grants for programs and resources in FY 2020, per the latest available data.[lxxxiii] The bulk of the grants — 84 percent — went to police enforcement of the drug war.

The Elizabeth Police Department received $218,200 from the Byrne Grant (also known as JAG) in FY 2020. JAG is a drug war-era federal program that provides grants for police resources to be used at the discretion of the police department. JAG is linked to increased arrest rates and racial disparities in policing, despite attempts to rectify such disparities.[lxxxiv] For every $100 increase in Byrne Grant funding since 1987, drug-related arrests increased by roughly 22 per 100,000 white residents and by 101 arrests per 100,000 Black residents.[lxxxv]

The remaining grant funds, roughly 19 percent, went to body armor purchases for police officers and Drunk Driving Enforcement, which consists of overtime pay for increased numbers of police in certain locations and incentives for ticket writing. Additionally, police departments are entitled to $95 of the $100 surcharge resulting from a drunk driving conviction in their community, per New Jersey State Statute 39:4-50.8.[lxxxvi]

In addition to the funding listed above, the Elizabeth police department can also receive funding from Municipal Alliances, which are local organizations composed of various stakeholders, including teachers, school staff, social service agency representatives, government officials, and police. Funding is collected from fines and fees from drug offenses to be used to fund programs at the discretion of the Alliance.[lxxxvii] Union County’s Municipal Alliances, the county in which Elizabeth is located, typically uses some of these funds for programs run by police, such as Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.), Law Enforcement Against Drugs (L.E.A.D.), and Cops in Schools, all of which provide dollars to police departments.[lxxxviii] In FY 2020, Elizabeth’s Municipal Alliance received about $57,000 dollars.[lxxxix]

Municipal Alliances are also responsible for the passage of over 1,000 local private property ordinances across the state that add new punishments related to drug and alcohol use, indirectly funneling money to police departments by increasing arrest rates and police activity.[xc] Moreover, programs like D.A.R.E. that promote abstinence have not curbed drug use.[xci]

Police Budget in Context

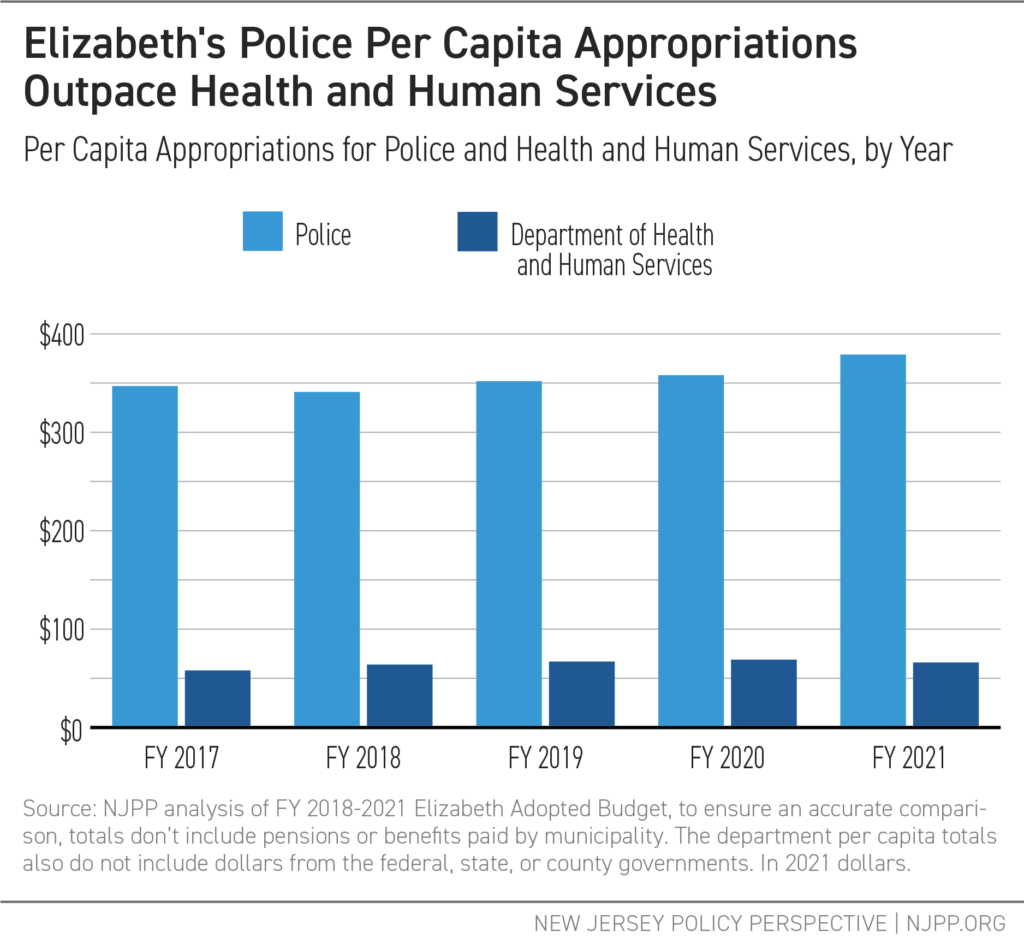

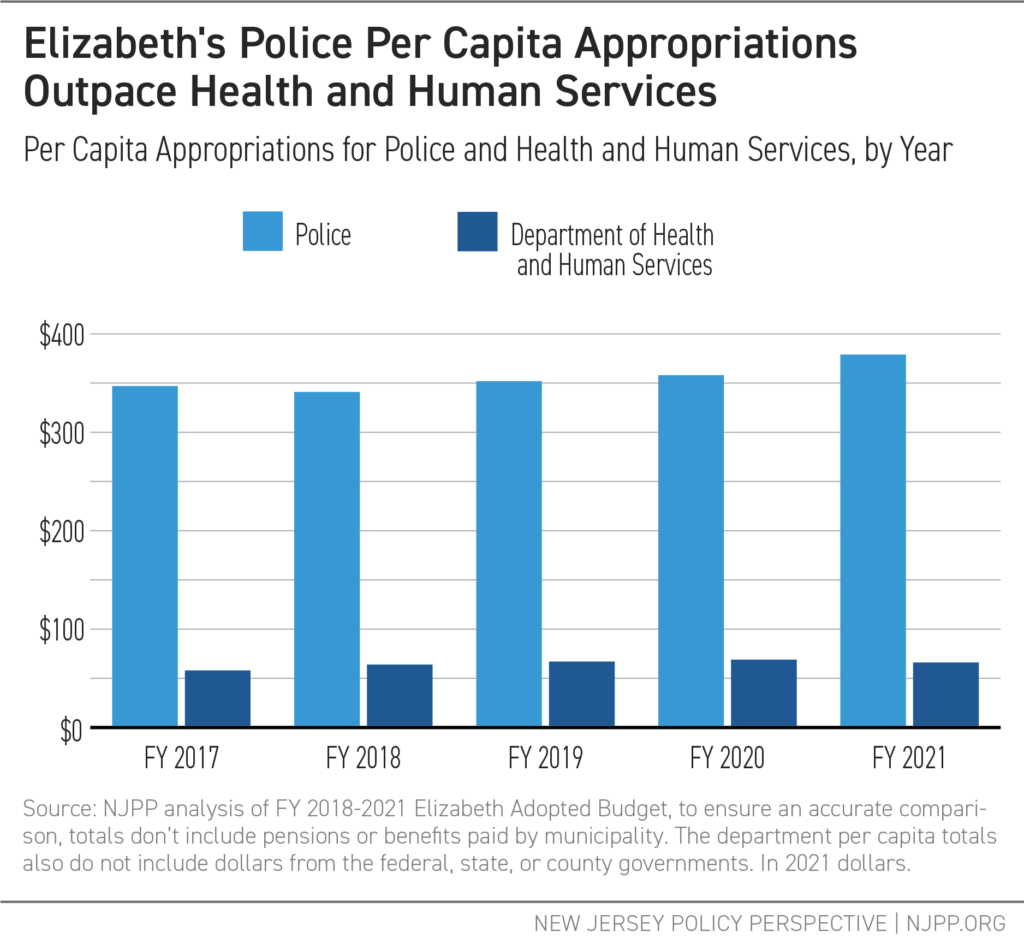

Elizabeth’s municipal police budget of $52 million, about $379 per capita, is 5.7 times greater than the city’s Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHS) $9.1 million budget.[xcii] The appropriations for the entire DHS equate to a mere $66 per capita.[xciii]

As of FY 2021, DHS employs 96 full-time and 44 part-time employees in numerous divisions and offices.[xciv] The city’s DHS provides various programs and services, including opportunities for rental assistance, help with prescription drug payments for struggling residents, and burial assistance for those who cannot afford funerals for their loved ones.[xcv] They also provide free health clinics, vaccines, and screenings for the under- or uninsured through the Public Health Nurses Division.[xcvi] Between FY 2020 and FY 2021, the police budget increased by $2.8 million (or 5.8 percent), while the funding for DHS decreased by $401,000 (or 4.2 percent).[xcvii] This is an increase of approximately $20 per capita for police.

Despite increased police funding, Elizabeth has not seen a significant increase in police performance or public safety. A standard measure of police performance is the clearance rate, which is the percentage of crimes that result in police locating and bringing charges against a likely suspect. In 2020, the latest available data states that the Elizabeth Police Department had a clearance rate of 13.2 percent,[xcviii] a rate that has remained stable since at least 2017, despite increases in funding.[xcix]

Gloucester County

Gloucester County is a predominately white, more-rural county that is home to roughly 300,000 people.[c] The county is comprised of 24 municipalities which vary tremendously in population size, density, demographic diversity, and income levels. These municipalities have a total of 19 local police departments, as well as a county-level sheriff’s office.[ci]

Police Appropriations

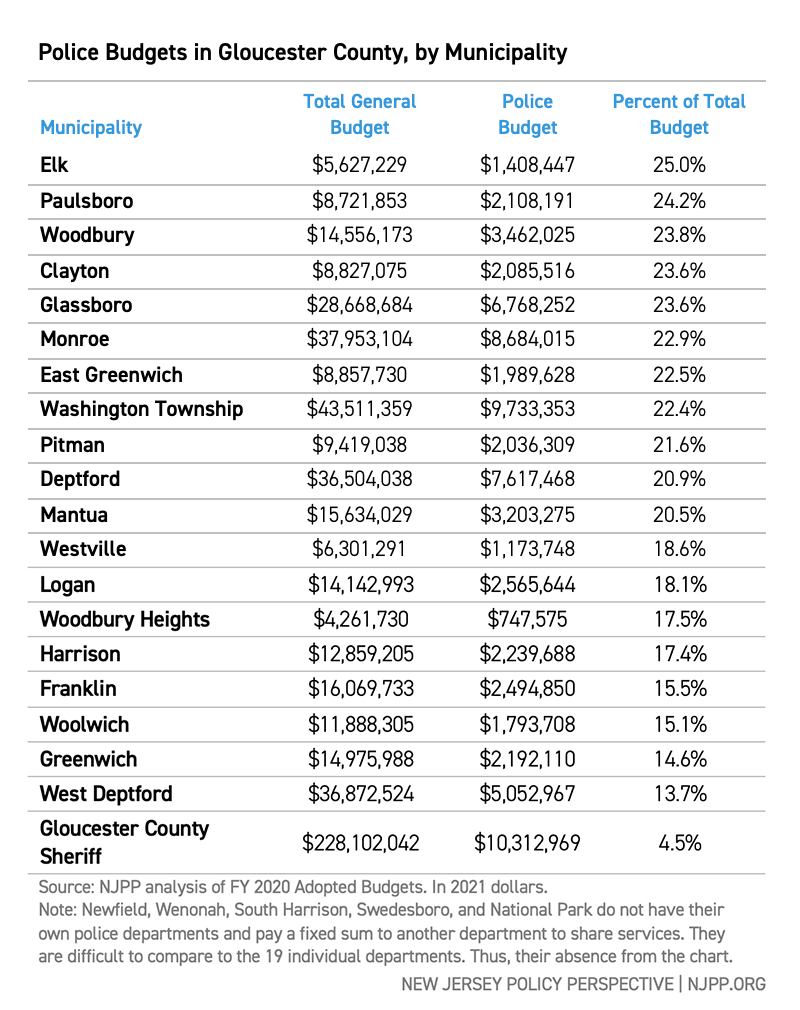

In FY 2020, the 19 local police departments and county-level sheriff’s office in Gloucester County received more than $77 million in funding, according to the most recent data available.[cii] This averages $257 per capita,[ciii] with the average municipal police budget at about 20 percent of its respective municipal budget, ranging from about 14 percent to 25 percent across municipalities. Please note that the police budget totals below do not include payments made for pensions and other benefits for police officers.

Additional Revenue

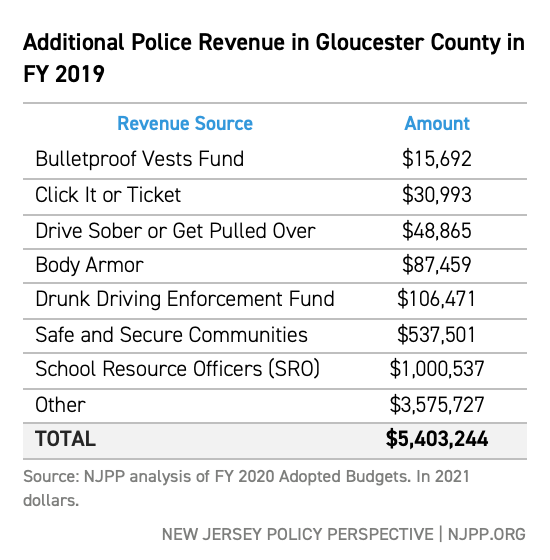

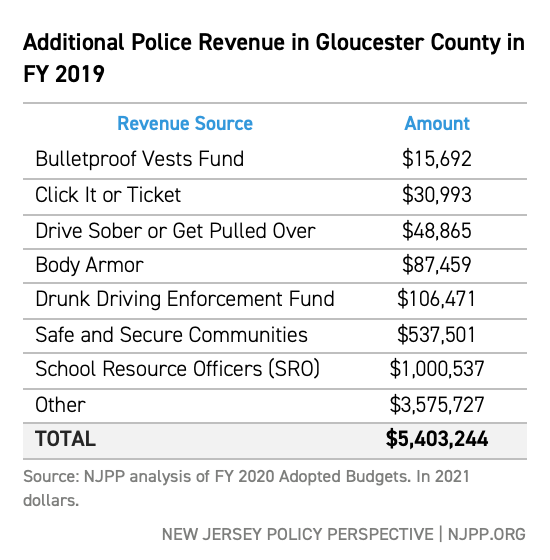

In addition to local revenue, law enforcement agencies in Gloucester County received revenue through a variety of grant programs in FY 2019. Notably, the “Click It or Ticket” (CIOT) and the “Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over” (DSOGPO) programs provide grant funding for an increased, “highly-visible” police presence.[cv] Specifically, the programs fund overtime enforcement to improve the “threat of a traffic ticket.”[cvi] In addition to the unavoidable time spent on court appearances or paperwork, overtime is used to make police more visible by putting additional officers in certain targeted areas, especially during holidays. Each campaign spans approximately two weeks per year, during which police track how many citations they were able to issue.

In FY 2019, Gloucester County’s police departments received over $79,000 and issued 4,163 citations in a total of just over four weeks through these programs.[cvii] All of the county’s police departments participated except Franklin.[cviii]

Programs like these engage in a strategy known as “proactive policing,” specifically “hot spots” policing,[cix] which involves preemptively sending officers to targeted areas to deter and reduce crime.[cx] However, the increased volume of police results in more ticketing and traffic stops, and a higher frequency of interactions between police and civilians in targeted locations, which are typically areas with higher rates of Black and brown people and poverty.[cxi] Increased police stops and ticketing also significantly increases the possibility of escalation. In 2020, nearly 11 percent of all U.S. police killings began with a routine traffic stop.[cxii]

Other sources of police funding in Gloucester County include:

- School boards using education-dedicated dollars to pay for police presence at schools, School Resource Officers (SROs), which provided about $1 million to Gloucester County police departments in FY 2019

- Grants from private companies or institutions: In FY 2020, Walmart gave Monroe’s police department and community affairs $6,073 in the form of a “Community Grant.”[cxiii]

- State and federal programs that pay for or provide police resources: For example, in FY 2019, municipalities in Gloucester County received about $100,000 in state and federal grants for bulletproof vests and body armor alone.[cxiv]

The chart below shows the dollars Gloucester County received in FY 2019, the most recent comprehensive data, that were authorized to fund policing.[cxv] These funds, totaling over $5.4 million, are outside of the dedicated funds in the police budgets.[cxvi]

Additionally, various Municipal Alliances in Gloucester County received a total of $247,428 in funding in FY 2019.

As noted in the analysis of Elizabeth’s budget, police departments also have access to new technology or equipment through capital improvement funding. Capital improvement funds are set aside to be used for parks, municipal buildings, and other community improvements. Typically, these projects take years to implement and, as such, are funded over a number of years. Some notable projects for police departments in Gloucester County include:

- $70,860 for tasers, long guns, and new radar for police vehicles for Monroe, in FY 2020.[cxvii] $3,543 will be taken from the capital improvement fund while the remaining $67,317 is authorized to be taken on as debt.

- $133,622 for police equipment for Mantua in FY 2020.”[cxviii] $6,681 will be taken from the capital improvement fund while the remaining $126,941 is authorized debt.

- $956,996 for various police projects in Washington Township, including body cameras, ballistic shields, vehicles, and other expenses noted in the budget as “technology” in FY 2019.[cxix] $47,850 was taken from the capital improvement fund while the remaining $909,147 was authorized debt.

Police Budget in Context

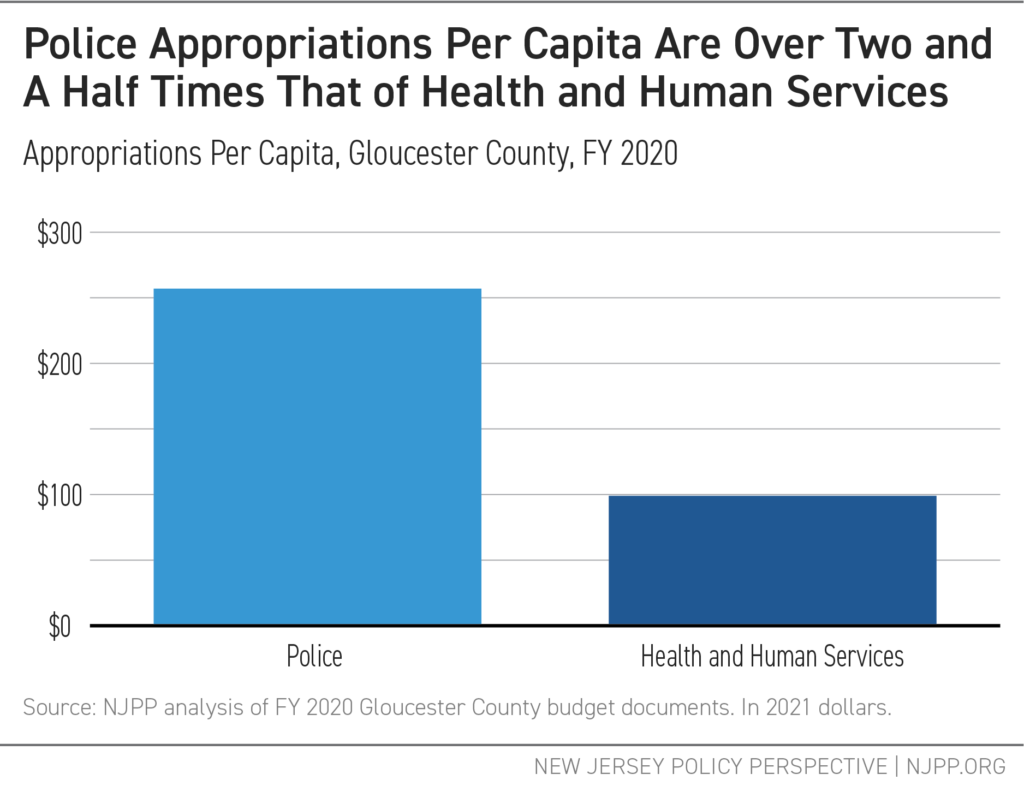

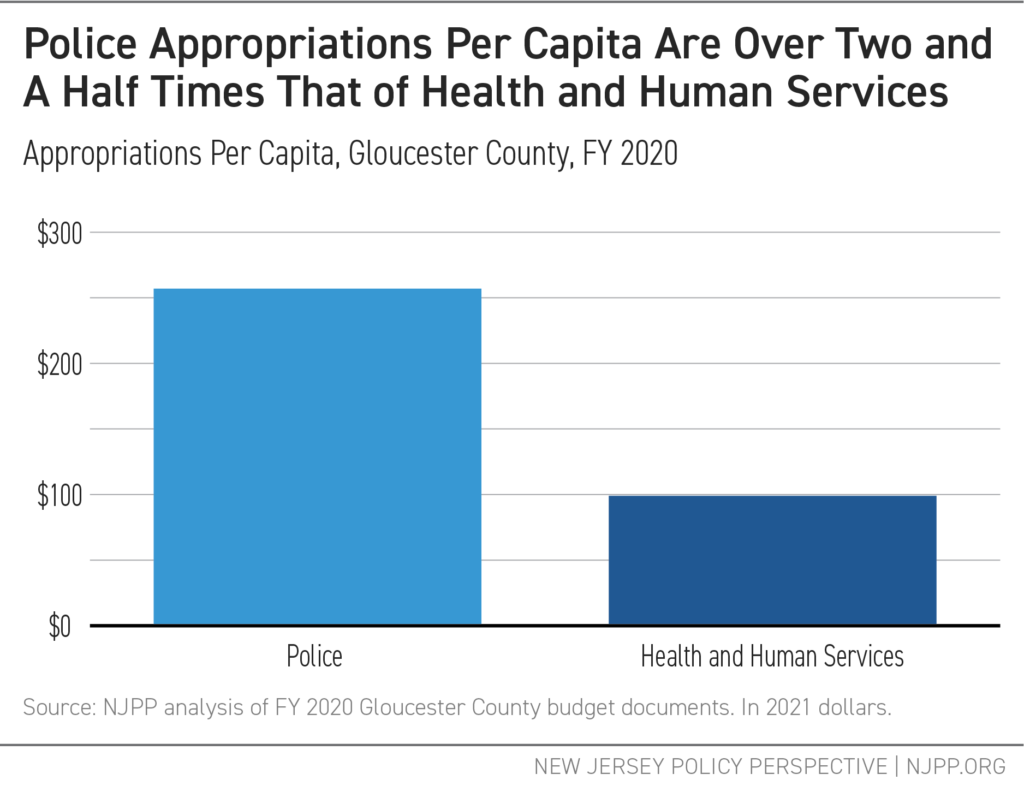

Gloucester County invests a high proportion of its budgets for policing, and the opportunity costs of this investment are significant. In FY 2020, total police appropriations were more than two and a half times that of total health and human services (HHS) budgets across the county, with police appropriations averaging about $257 per capita and HHS averaging $99 per capita.[cxx]

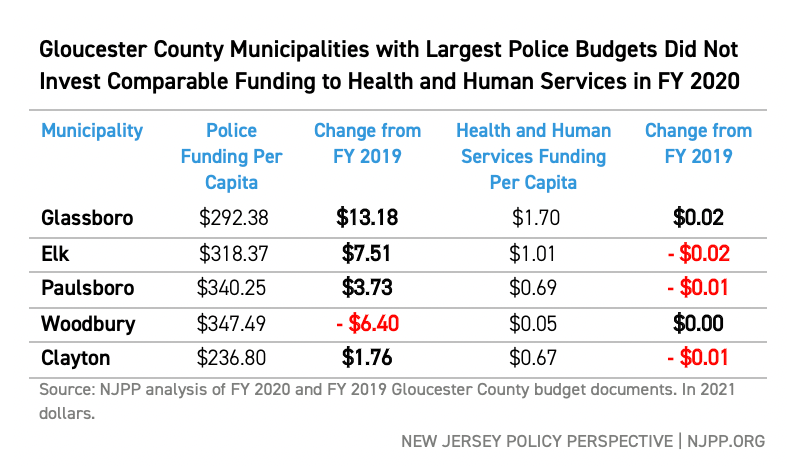

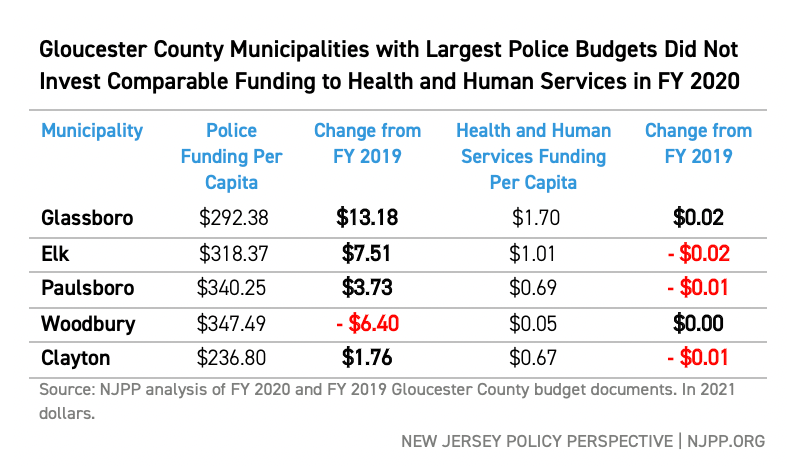

As the table below shows, Gloucester County municipalities with the largest share of their budgets going to police departments tend to increase funding for police while funding for health and human services remains stagnant or decreases.[cxxi]

Despite increased funding and resources, Gloucester County police departments reported a clearance rate of 25 percent on average in 2020,[cxxii] meaning that of the crimes reported, only 25 percent of them resulted in police locating and charging likely suspects. In 2017, the rate was just over 37 percent, since then it has remained stagnant with an average of 25 percent.[cxxiii]

A Way Forward: Policy Recommendations

The current system of public safety relies on a model of justice that disproportionately funds and prioritizes policing, rather than communities. This model continues to target Black residents through racial profiling, aggressive policing, and mass incarceration.[cxxiv] This also forces police officers to handle issues for which they often are not trained, such as in mental health, domestic violence, and substance use disorder.[cxxv]

This section offers two main strategies that must be taken together to provide safer and healthier communities.

Invest in Communities

Although local governments have historically used policing and incarceration as primary crime reduction strategies, methods to strengthen communities and address the structural roots of crime that have proved more effective do exist. One major way to promote safe and healthy communities and get to the root cause of crime is to invest in health and human services. Broader investments in communities will also be required. Some examples include investments in:

Health care

There is a strong correlation between health care access and involvement in the criminal justice system. Research from the City of Camden demonstrates a significant relationship between high use of hospital emergency departments and frequent arrests, suggesting that a holistic approach to health care may reduce arrest rates.[cxxvi] Moreover, broader access to health care, especially substance use disorder treatment, is consistently linked to crime reduction.[cxxvii] Across the U.S., increased health care access reduced violent crime by 5.8 percent and property crime by 3 percent, with an estimated savings of $13 billion to taxpayers due to crime reduction.[cxxviii]

Neighborhood restoration

With community support and input, investments in parks, green spaces, and the restoration of blighted or vacant land can have positive outcomes on public safety. Increasing access to green spaces is shown to reduce violent crime[cxxix] and improve health outcomes for residents.[cxxx] Restoring vacant lots is also shown to reduce violence in urban areas.[cxxxi] Maintenance of the physical environment in a community also strengthens the social environment, fostering a sense of connectedness that creates a willingness to intervene and social contracts that have been shown to prevent crime.[cxxxii]

Quality early childhood education

Early childhood education is shown to have positive outcomes for children and parents by providing stable child care and increasing access to other opportunities. Access to early childhood education correlates with increased academic achievement, stronger parent-child relationships, and a significant reduction in the likelihood of being charged with a crime.[cxxxiii]

Community centers and nonprofits

An increased number of local organizations actively working to reduce violence and strengthen communities have demonstrated positive outcomes, including crime reduction. For example, drawing on a panel of 264 cities spanning more than 20 years, every ten additional organizations focusing on crime and community life leads to a 9 percent reduction in the murder rate, a 6 percent reduction in the violent crime rate, and a 4 percent reduction in the property crime rate, a 2017 study found.[cxxxiv]

Community-based violence interruption programs

Informal and formal social networks are effective crime prevention tools. That’s because building strong community relationships and mutual trust among residents has been shown to reduce crime.[cxxxv] Community-based violence interruption programs incorporate this knowledge by having trusted neighbors and community members partnered with trained staff, and some programs have proven effective in preventing violence.[cxxxvi] The Newark Community Street Team (NCST) can serve as a model for this kind of program in New Jersey.[cxxxvii]

Invest In Alternative Response Teams

Police are first responders to situations for which they don’t have sufficient training, such as in areas of domestic violence, mental health, substance use disorders, and housing insecurity. These encounters between the police and people in crisis too often end in arrest, violence, or emergency room transport, and without needed referral to long-term support.

Thankfully, there are alternative models to support people in crisis that do not center policing.

Some of these models include teams of health care professionals and social workers that respond to calls for service instead of police. Other models include a social worker and a police officer responding in tandem.

These models are not new. Beginning at least 40 years ago, research has consistently shown the effectiveness of alternative response teams.[cxxxviii] For instance, a three-year study from 1974 looked at an alternative service model involving a team of police and social workers whose objective was crisis intervention, not arrest. There was a marked reduction in referrals to court and lowered recidivism rates.[cxxxix] It was also noted in these studies that there was a need for community services among the recipients of interventions, such as access to stable housing, employment service, and an emergency petty cash fund.[cxl]

Today, many localities are exploring alternative models based on successful models (see box below). Ithaca, New York is considering replacing the city’s entire 63-officer, $12.5 million-per-year department with a “Department of Community Solutions and Public Safety.”[cxli] This department would include armed “public safety workers” and unarmed “community solution workers,” all of whom will report to a civilian director instead of a police chief.[cxlii] Further, California is considering the C.R.I.S.E.S. Act, which would provide funding to community-based emergency response teams to serve as alternatives to police for a wide range of issues, including domestic disputes and mental health crises.[cxliii]

There is also evidence that police departments are open to alternative models so they can be more effective and increase community trust. In Minnesota, 69 percent of police chiefs surveyed across 40 different departments reported that collaboration with social workers or other mental health service providers would reduce avoidable casualties and build or increase police-community trust.[cxliv]

Examples of Successful Programs

Communities around the country have successfully implemented crisis response teams that serve as an alternative to and work in tandem with the police. These programs can serve as examples of how to reimagine public safety through person-centered responses.

CAHOOTS

The Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets (CAHOOTS) program, serving Eugene, Oregon since 1989, provides an innovative community-based public safety system that deploys crisis response teams. Each team consists of a medical professional and a crisis worker with training in mental health interventions.[cxlv]

According to the most recent program evaluation, CAHOOTS diverted 5 to 8 percent of 911 calls from the Eugene Police Department between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019.[cxlvi] This means that up to 8 percent of the calls placed to dispatch that would normally involve police being sent to the scene result in no police or police resources arriving on the scene at all.[cxlvii] If calls for service directly to CAHOOTS are taken into account rather than just 911 calls, the diversion rate could be as high as 20 percent.[cxlviii]

The CAHOOTS program saved the City of Eugene an estimated average of $8.5 million in annual public safety spending between 2014 and 2017.[cxlix]

STAR

In 2020, Denver launched the Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) pilot program closely modeled on CAHOOTS, where specific kinds of 911 calls were approved for an alternative, non-police response. Calls that involved injuries, weapons, threats, or any other types of violence were excluded.

Data gathered during the pilot period revealed that the STAR program could reduce Denver police calls by almost 3 percent.[cl] Of the calls the STAR team responded to, 61 percent of individuals served were identified as having a mental health condition, and 41 percent of individuals served were transported to other support sites such as shelters or mental health crisis centers.[cli] These individuals were able to receive specialized care or transportation to needed service providers through STAR. Due to the positive response, the City of Denver plans to expand the STAR program in 2021.[clii]

Newark Community Street Team

The Newark Community Street Team (NCST) is a trauma-informed approach to public safety that centers health and prevention in Newark, New Jersey. The program began in 2015 with the support of Mayor Ras Baraka. NCST provides Safe Passage at schools, operates a Trauma Recovery Center, and has a robust victim services program, including a partnership with University Hospital’s Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Program. NCST also engages in High Risk Intervention (HRI) in Newark.[cliii] NCST is also currently leading efforts to create a harm reduction centered alternative emergency response to overdose in Newark, building off its community-based model of care and intervention.

The HRI team responds to reports of violence from the community or law enforcement.[cliv] HRI connects those involved to supportive counseling, crisis intervention assessment and mediation, and referrals to outside resources to restore peace and avoid arrest and incarceration.[clv] From 2016 to 2020, there have been record-low homicide rates in Newark.[clvi] This trend correlates with the existence of the NCST.[clvii] In 2018, Mayor Baraka credited NCST with not only the reduction of crime but also increased economic development.[clviii] The NCST offers a model for what decreased police intervention could look like in New Jersey.

|

Conclusion

New Jersey’s local governments, from counties to urban centers to small municipalities, spend a large share of their budgets on policing in the name of public safety. However, evidence shows that many policing policies and outcomes harm civilians, especially Black residents.

New Jersey has the opportunity to be a leader in the fight for equity and justice. But to do so, the state must respond to and invest in the unique needs of historically marginalized communities by exploring alternative models to policing. These models, like police departments, may look a little different in every community. Elizabeth would likely need their own response team, while municipalities across Gloucester County could share services. Yet, whatever the model, the throughline remains a directive to invest in resources like mental health counseling, affordable housing, and employment opportunities, to build and restore communities and center harm reduction while developing real police accountability measures.

End Notes

[i] USA Today. (2020). Tracking protests across the USA in the wake of George Floyd’s death. https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/graphics/2020/06/03/map-protests-wake-george-floyds-death/5310149002/

[ii] Geller, A., Fagan, J., Tyler, T., & Link, B. G. (2014). Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. American Journal of Public Health, 104(12), 2321–2327. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046

[iii] American Public Health Association (APHA). (2018). Addressing Law Enforcement Violence As A Public Health Issue. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/29/law-enforcement-violence

[iv] American Public Health Association (APHA). (2020). Mass Incarceration Supplement. https://www.apha.org/news-and-media/news-releases/ajph-news-releases/2020/mass-incarceration-supplement

[v] Data obtained from Washington Post Segregation Database found: Williams & Emamdjomeh. (2018). America is more diverse than ever — but still segregated. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/national/segregation-us-cities/

[vi] All appropriations in this report have been adjusted to 2021 dollars.

[vii] Walker, S. (1980) Popular Justice: A History of American Criminal Justice. Pg. 20. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[viii] Hasset-Walker. (2021). How Your Start is How You Finish? The Slave Patrol and Jim Crow Origins of Policing. Human Rights Magazine, The American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/civil-rights-reimagining-policing/how-you-start-is-how-you-finish/

[ix] Potter. (2003). The History of Policing in the United States. EKU School of Justice Studies. Pg. 3. https://plsonline.eku.edu/sites/plsonline.eku.edu/files/the-history-of-policing-in-us.pdf

[x] Hansen. (2019). Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing. National Law Enforcement Museum. https://nleomf.org/slave-patrols-an-early-form-of-american-policing/ /

[xi] Lepore. (2020). The Invention of Police. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/07/20/the-invention-of-the-police

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Hasset-Walker. (2021). How Your Start is How You Finish? The Slave Patrol and Jim Crow Origins of Policing. Human Rights Magazine, The American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/civil-rights-reimagining-policing/how-you-start-is-how-you-finish/

[xiv] Walker, S. (1980) Popular Justice: A History of American Criminal Justice. Pg. 20. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[xv] Luxenberg, S. (2019) The Jim Crow Car: The North, the South and the forgotten origins of racial separation. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/magazine/wp/2019/02/20/feature/the-forgotten-northern-pre-civil-war-origins-of-jim-crow/. There is also a book on this subject: https://wwnorton.com/books/separate/

[xvi] Potter. (2003). The History of Policing in the United States. EKU School of Justice Studies. Pg. 3. https://plsonline.eku.edu/sites/plsonline.eku.edu/files/the-history-of-policing-in-us.pdf

[xvii] Ibid. Pg. 3-5

[xviii] Robinson, M. (2017). From the Slave Codes to Mike Brown: the brutal history of African Americans and law enforcement. USAPP– American Politics and Policy. Pg. 1-2. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/85472/1/usappblog-2017-10-05-from-the-slave-codes-to-mike-brown-the-brutal.pdf

[xix] Goldberg, D. (2016) The Retreats of Reconstruction: Race, Leisure, and the Politics of Segregation at the New Jersey Shore. Fordham University Press.

[xx] Rojas & Atkinson. (2017). Five Days of Unrest that Shaped and Haunted Newark. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/11/nyregion/newark-riots-50-years.html

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Alexander. (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press.

[xxiv] Nixon. (1971). Special Message to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-drug-abuse-prevention-and-control

[xxv] Cooper. (2015). War on Drugs Policing and Police Brutality. Substance use & misuse, 50(8-9), 1188–1194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4800748/#R27

[xxvi] Lynch, M. (2012). Theorizing the role of the “war on drugs” in US punishment. Theoretical Criminology. Pg. 16. https://socialecology.uci.edu/sites/socialecology.uci.edu/files/users/lynchm/tc_war_on_drugs_final.pdf ; Urban Institute. (2020). Criminal Justice Expenditures: Police, Corrections, and Courts. https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/state-and-local-backgrounders/criminal-justice-police-corrections-courts-expenditures#Question3Police

[xxvii] Cooper. (2015). War on Drugs Policing and Police Brutality. Substance use & misuse, 50(8-9), 1188–1194. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4800748/#R27

[xxviii] National Research Council. (2014). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613. Pg. 34-36. https://www.nap.edu/read/18613/chapter/4#34

[xxix] Ibid. Pg. 46-47.

[xxx] Wagner & Bertram. (2020) “What percent of the U.S. is incarcerated?” (And other ways to measure mass incarceration). Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/01/16/percent-incarcerated/

[xxxi] National Research Council. (2014). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613. Pg. 34-36. https://www.nap.edu/read/18613/chapter/4#34

[xxxii] National Research Council. (2014). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/18613. Pg. 58. https://www.nap.edu/read/18613/chapter/4#34

[xxxiii] Ibid.

[xxxiv] Borden, T. (2016) Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States. Human Rights Watch. Pg. 4. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/12/every-25-seconds/human-toll-criminalizing-drug-use-united-states

[xxxv] U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI225219

[xxxvi] Federal Bureau of Prisons. (2021) Inmate Statistics. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp

[xxxvii] Baum. (2016). Legalize It All. Harper’s Magazine. https://harpers.org/archive/2016/04/legalize-it-all/

[xxxviii] Walmsley, R. (2018) World Prison Population List: Twelfth Edition. Institute for Criminal Policy Research. Pg. 6. https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_12.pdf. Note that some countries may not report complete prison/detention lists.

[xxxix] FBI: UCR Crime in the United States 2019 data table. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/table-29

[xl] NJPP calculation using FBI UCR data for all non-traffic arrests and arrests for “Drug Abuse Violations — Grand Total” reported by participating New Jersey law enforcement agencies, 1986 and 2019. Available at https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/home.

[xli] Mellor. (2021). A War on Us: How Much New Jersey Spends Enforcing the War on Drugs. New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/a-war-on-us-how-much-new-jersey-spends-enforcing-the-war-on-drugs/ ; NJPP calculation using FBI UCR data for all non-traffic arrests and arrests for “Drug Abuse Violations — Grand Total” reported by participating New Jersey law enforcement agencies, 1986 and 2019. Available at https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/home.

[xlii] NJPP calculation using FBI UCR data for all non-traffic arrests and arrests for “Drug Abuse Violations — Grand Total” reported by participating New Jersey law enforcement agencies, 1986 and 2019. Available at https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/home.

[xliii] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2018R2/NSDUHDetailedTabs2018.pdf

[xliv] State of New Jersey Department of Corrections. (2021) Offender Statistics. p.36. https://www.state.nj.us/corrections/pdf/offender_statistics/2021/Entire%20Offender%20Characteristics%202021.pdf

[xlv] Data for New Jerseyans that identify as “Black or African American alone or in combination,” (2020). Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/race-and-ethnicity-in-the-united-state-2010-and-2020-census.html Note that Census data for Black or African American alone or in combination includes Black/African American residents identifying as Hispanic, whereas the corrections data splits Hispanic out as a separate category.

[xlvi] Ibid. This includes white New Jerseyans that identify as more than one race or ethnicity.

[xlvii] Mellor. (2021). A War on Us: How Much New Jersey Spends Enforcing the War on Drugs. New Jersey Policy Perspective. Pg. 4. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/a-war-on-us-how-much-new-jersey-spends-enforcing-the-war-on-drugs/ ;

Movement for Black Lives. “End the War on Drugs.” Policy Platform. https://m4bl.org/policy-platforms/end-the-war-on-drugs/

[xlviii] Office of the Attorney General. (2020). Use of Force Policy. The State of New Jersey. Pg. 6. https://www.nj.gov/oag/force/docs/UOF-2020-1221-Use-of-Force-Policy.pdf

[xlix] National Institute of Justice. Overview of Police Use of Force. (2020). https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/overview-police-use-force

[l] University of Chicago Law School – Global Human Rights Clinic. (2020). Deadly Discretion: The Failure of Police Use of Force Policies to Meet Fundamental International Human Rights Law and Standards. Global Human Rights Clinic. Pg. 2 https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=ihrc ;

US Commission on Civil Rights (2018). Police Use of Force: An Examination of Modern Policing Practices. Pg. 15. https://www.usccr.gov/files/pubs/2018/11-15-Police-Force.pdf

[li] American Public Health Association (APHA). (2018). Addressing Law Enforcement Violence As A Public Health Issue. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/29/law-enforcement-violence

[lii] NJPP analysis of AG’s Use of Force Database.

[liii] Ibid.

[liv] The Washington Post. Fatal Force Database (2021). https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/?nid

[lv] The Washington Post. Fatal Force Database (2021). https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/?nid

[lvi] NJPP analysis of The Washington Post. Fatal Force Database (2021). https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/?nid & Mapping Police Violence Database (2021). https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Data from Mapping Police Violence: https://public.tableau.com/profile/ssinyangwe#!/vizhome/PoliceViolenceperPD/PoliceKillingsbyState

[lix] Gur, O. (2010). Persons with mental illness in the criminal justice system: Police interventions to prevent violence and criminalization. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations. Pg. 3. 17-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332581003799752

[lx] The Institute for Criminal Justice Training Reform. (2021).

https://www.trainingreform.org/state-police-training-requirements

[lxi] Graph from an analysis of The Washington Post. Fatal Force Database (2021). https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/?nid & Mapping Police Violence Database (2021). https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/ – data is between 1/2015 and 4/2021. Note that there may be variation across the reporting of domestic disputes that could classify some involving assault as nonviolent.

[lxii] Fuller, Lamb, Biasatti, & Snook. (2015). Overlooked in the Undercounted: The Role Of Mental Illness In Fatal Law Enforcement Encounters. Pg. 1. Treatment Advocacy Center. https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/overlooked-in-the-undercounted.pdf

[lxiii] ACLU of New Jersey. (2013). The Crisis Continues Inside Internal Affairs. https://www.aclu-nj.org/files/3413/6059/3876/ACLU_NJ_Internal_Affairs.pdf ;

Reilly. (2015). Here’s What Happens When You Complain to Cops About Cops. Huffpost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/internal-affairs-police-misconduct_n_5613ea2fe4b022a4ce5f87ce

[lxiv] NJPP analysis of The Washington Post. Fatal Force Database (2021). https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/?nid & Mapping Police Violence Database (2021). https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/ – data is between 1/2015 and 4/2021.

[lxv] Ibid.

[lxvi] Sullivan & Everett. (May 2019). Residents say this troubled N.J. police department ignores excessive force complaints. Records reveal it hasnʼt upheld a case in years. NJ.com. https://www.nj.com/politics/2019/05/residents-say-this-troubled-nj-police-department-ignores-excessive-force-complaints-records-show-it-hasnt-upheld-a-case-in-years.html

[lxvii] Ibid.

[lxviii] Police get additional overtime compensation from private citizens and companies for a variety of reasons, including monitoring the street during construction projects or during special events. These dollars would not be accounted for in the municipal budget.

[lxix] New Jersey Demographics, data linked to US Census. https://www.newjersey-demographics.com/cities_by_population

[lxx] U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). New Jersey. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/elizabethcitynewjersey,NJ/PST045219

[lxxi] Ibid. All dollars taken from the census data are 2021 dollars and have been adjusted from 2019 dollars.

[lxxii] Elizabeth Municipal Ordinance. 2.56.110 – Police Department Administration and Personnel. (2021). https://library.municode.com/nj/elizabeth/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT2ADPE_CH2.56PODE_ARTIIADPE_2.56.110ADPE

[lxxiii] NJPP analysis of FY2021 Adopted Budget

[lxxiv] NJPP analysis of Elizabeth’s FY 2021 User Friendly Budget personnel costs

[lxxv] Ibid. This calculation is based on the number of officers employed at the time, which was

[lxxvi] NJPP analysis of FY2018 – FY2021 Adopted Budgets. All dollars used in analysis are in 2021 dollars.

[lxxvii] NJPP analysis of total police personnel costs in Elizabeth’s FY2021 User Friendly Budget

[lxxviii] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 User Friendly Budget.

[lxxix] Ibid.

[lxxx] Contract Between City of Elizabeth and PBA4. Pg. 23. https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/20472639/elizabeth-and-pba-loc-4-2018.pdf

[lxxxi] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 Adopted Budget – capital improvements

[lxxxii] Local Finance Board – Capital Budgets And Capital Improvement Programs. https://www.nj.gov/dca/divisions/dlgs/resources/rules_docs/5_30/njac_5304.pdf

[lxxxiii] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 Adopted Budget. In 2021 dollars. Note that these grants are not listed as “anticipated” for FY 2021.

[lxxxiv] Cox & Cunningham. (August 2017). Financing the War on Drugs: The Impact of Law Enforcement Grants on Racial Disparities in Drug Arrests. Pg. 26-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3035640

[lxxxv] Ibid.

[lxxxvi] NJ Department of Law and Public Safety. (2021). Drunk Driving Enforcement Fund. https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/grants/index.html

[lxxxvii] Governor’s Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. https://gcada.nj.gov/alliance/

[lxxxviii] Union County, New Jersey. Municipal Alliance Programs. https://ucnj.org/departments/human-services/alliance-to-prevent-alcoholism-and-drug-abuse/municipal-alliances/municipal-alliance-programs/

[lxxxix] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 Elizabeth Adopted Budget.

[xc] Mellor. (2021). A War on Us: How Much New Jersey Spends Enforcing the War on Drugs. New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/a-war-on-us-how-much-new-jersey-spends-enforcing-the-war-on-drugs/

[xci] West, S. L., & O’Neal, K. K. (2004). Project D.A.R.E. outcome effectiveness revisited. American Journal Of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.6.1027

[xcii] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 Adopted Budget, In order to make an apples-to-apples comparison, this section compares the municipal police budget itself, without additional police revenue.

[xciii] This does not include federal or state dollars for programs like TANF or SSI. This comparison is salaries and wages and day-to-day operating expenses of the departments.

[xciv] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 Adopted Budget. Pg. 129. https://www.elizabethnj.org/ArchiveCenter/ViewFile/Item/75

[xcv] Department of Health and Human Services. City of Elizabeth. https://www.elizabethnj.org/323/Human-Services

[xcvi] Public Health Nursing. City of Elizabeth. https://www.elizabethnj.org/328/Public-Health-Nursing

[xcvii] NJPP analysis of FY 2021 Adopted Budget for Elizabeth

[xcviii] 2020 Uniform Crime Report. https://www.njsp.org/ucr/uniform-crime-reports.shtml

[xcix] NJPP analysis of 2017-2020 Uniform Crime Reports. Note clearance rates do not track important information like if the person who was arrested was the person who committed the crime, drug and other nonviolent crime, and many police initiated encounters.

[c] U.S. Census Bureau. (2019) Gloucester County, New Jersey. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/gloucestercountynewjersey,US/RHI225219

[ci] NJPP analysis of municipal documents. This does not include the Prosecutor’s Office, Department of Corrections, or Rowan University’s police department in Glassboro.

[cii] NJPP analysis of FY 2020 municipal budgets. This number does not include the budgets for the Department of Corrections or the County Prosecutor’s Office.

[ciii] This is an underestimate given that the dollars for shared service agreements are not included.

[civ] Newfield, Wenonah, South Harrison, Swedesboro, and National Park do not have their own police departments and pay a fixed sum to another department to share services. They are difficult to compare to the 19 individual departments. Thus, their absence from the chart.

[cv] New Jersey Department of Public Safety, Division of Traffic Safety. (2019). Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over. https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/youlose.html

[cvi] New Jersey Department of Public Safety, Division of Traffic Safety. (2019). Click It Or Ticket. https://www.state.nj.us/oag/hts/clickitorticket.html

[cvii] “Click it or Ticket,” p. 12: https://www.state.nj.us/oag/hts/downloads/CIOT_2019_Final_Report.pdf; “Drive Sober or Get Pulled Over,” p. 11: https://www.nj.gov/oag/hts/downloads/2019_DSOGPO_Report-WEB.pdf

[cviii] Ibid.

[cix] National, A. O. S. E. A., Division, O. B. A. S. S., Committee, O. L. A. J., & Committee, O. P. P. E. O. (2018). Proactive policing : Effects on crime and communities. Pages 1-3. ProQuest Ebook Central

[cx] Ibid.

[cxi] American Public Health Association (APHA). (2018). Addressing Law Enforcement Violence As A Public Health Issue. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/29/law-enforcement-violence

[cxii] Mapping Police Violence Database (2021). https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/ssinyangwe/viz/PoliceViolenceperPD/KillingsbyEncounterType

[cxiii] NJPP analysis of municipal budget. More information for Walmart’s community grant program: https://walmart.org/how-we-give/local-community-grants. In 2021 dollars.

[cxiv] NJPP analysis of Gloucester County municipal budgets. In 2021 dollars.

[cxv] Dollars from the MAADA grants are eligible to be used in other ways aside from policing and not all these dollars go to police departments, but there is no explicit breakdown in the municipal budgets to illustrate what share of these dollars go to programs outside of police departments.

[cxvi] This includes dollars given to police departments from municipalities that do not have their own police department as a contribution for the shared service.

[cxvii] NJPP analysis of FY2020 Adopted Budget for Monroe, Gloucester County. In 2021 dollars. Total estimated costs are over $200,000, but the remainder is to be funded in future years.

[cxviii] NJPP analysis of FY2020 Adopted Budget for Mantua, Gloucester County. In 2021 dollars. Total estimated costs are over $640,000, but the remainder is to be funded in future years.

[cxix] NJPP analysis of FY2019 Adopted Budget for Washington Township, Gloucester County. In 2021 dollars.

[cxx] NJPP analysis of various FY2020 municipal and county budget documents for Gloucester County.

[cxxi] NJPP Analysis of FY 2019 and FY 2020 Adopted Budgets. All adjusted for 2021 dollars.

[cxxii] 2020 Uniform Crime Report. https://www.njsp.org/ucr/uniform-crime-reports.shtml

[cxxiii] NJPP analysis of 2017-2020 Uniform Crime Reports. Note clearance rates do not track important information like if the person who was arrested was the person who committed the crime, drug and other nonviolent crime, and many police initiated encounters.

[cxxiv] Sawyer, W. (2020). Ten key facts about policing: Highlights from our work. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/06/05/policingfacts/

[cxxv] Stemen. (2017). The Prison Paradox: More Incarceration Will Not Make Us Safer. The Vera Institute. https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/for-the-record-prison-paradox-incarceration-not-safer/legacy_downloads/for-the-record-prison-paradox_02.pdf

[cxxvi] Milgram, A., et al. (2018). Integrated Health Care and Criminal Justice Data — Viewing the Intersection of Public Safety, Public Health, and Public Policy Through a New Lens: Lessons from Camden, New Jersey. Harvard Kennedy School. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/wiener/programs/pcj/files/integrated_healthcare_criminaljustice_data.pdf

[cxxvii] Wen, H. (2017). The effect of Medicaid expansion on crime reduction: Evidence from HIFA-waiver expansions. Journal of Public Economics, 154, 67–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.09.001;

Volger, J. (2017) Access to Health Care and Criminal Behavior: Short-Run Evidence from the ACA Medicaid Expansions. SSRN. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pam.22239

[cxxviii] Volger, J. (2017) Access to Health Care and Criminal Behavior: Short-Run Evidence from the ACA Medicaid Expansions. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3042267

[cxxix] Shepley, M., et al. (2019). The Impact of Green Space on Violent Crime in Urban Environments: An Evidence Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245119; Hoffman, A. (2020). Community service activities reducing hate crimes and extremism: A “green intervention” approach. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 48(3), 207–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2019.1625606

[cxxx] Kondo, M., Fluehr, J., McKeon, T., & Branas, C. (2018). Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(3), 445–. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030445

[cxxxi] Moyer, R., MacDonald, J., Ridgeway, G., & Branas, C. (2019). Effect of Remediating Blighted Vacant Land on Shootings: A Citywide Cluster Randomized Trial. American Journal of Public Health (1971), 109(1), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304752

[cxxxii] David-Ferdon, C. et al. (2016). A comprehensive technical package for the prevention of youth violence and associated risk behaviors. CDC. Pg. 31. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv-technicalpackage.pdf

[cxxxiii] Giovanelli, A., Hayakawa, M., Englund, M., Reynolds, A. (2018). African-American Males in Chicago: Pathways From Early Childhood Intervention to Reduced Violence, Journal of Adolescent Health, Pg. 80-86,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.08.012 ;

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2001). Favorable Long Term Effects of Head Start. NBER. https://www.nber.org/digest/aug01/favorable-long-term-effects-head-start

[cxxxiv] Sharkey, P., Torrats-Espinosa, G., & Takyar, D. (2017). Community and the Crime Decline: The Causal Effect of Local Nonprofits on Violent Crime. American Sociological Review, 82(6), 1214–1240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417736289

[cxxxv] Weisburd, D., White, C., Wire, S., & Wilson, D. (2021). Enhancing Informal Social Controls to Reduce Crime: Evidence from a Study of Crime Hot Spots. Prevention Science, 22(4), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01194-4

[cxxxvi] David-Ferdon, C. et al. (2016). A comprehensive technical package for the prevention of youth violence and associated risk behaviors. CDC. Pg. 33. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv-technicalpackage.pdf

[cxxxvii] To learn more about NCST see the box contained examples of successful programs and visit them at https://www.newarkcommunitystreetteam.org/

[cxxxviii] Watson, A., et al. (2019). Crisis Response Services for People with Mental Illnesses or Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Review of the Literature on Police-based and Other First Response Models. Vera Institute. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/crisis-response-services-for-people-with-mental-illnesses-or-intellectual-and-developmental-disabilities.pdf ;

Batko, S., et al. (2020) Alternatives to Arrests and Police Responses to Homelessness: Evidence-Based Models and Promising Practices. Urban Institute. Pg. 22-25. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103158/alternatives-to-arrests-and-police-responses-to-homelessness.pdf

[cxxxix] Treger, T. (1974). A Police-Social Work Team Model: Some Preliminary Findings and Implications for System Change. Crime and Delinquency. https://doi.org/10.1177/001112877402000308

[cxl] Ibid.

[cxli] Lowery, W. (2021). The Most Ambitious Effort Yet to Reform Policing May Be Happening In Ithaca, New York. GQ. https://www.gq.com/story/ithaca-mayor-svante-myrick-police-reform

[cxlii] Ibid.

[cxliii] French, P. (2021). California Bill That Promotes Alternatives To Policing Is Back Despite Governor’s Veto. The Appeal. https://theappeal.org/politicalreport/california-crises-act-2021/

[cxliv] Lamin, T. (2016). Police social work and community policing. Cogent Social Sciences, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2016.1212636

[cxlv] White Bird Clinic. (2020) CAHOOTS. https://whitebirdclinic.org/category/programs/cahoots/

[cxlvi] CAHOOTS Program Analysis. (2019). Pg. 8. https://www.eugene-or.gov/DocumentCenter/View/56717/CAHOOTS-Program-Analysis

[cxlvii] Ibid.

[cxlviii] Ibid.

[cxlix] White Bird Clinic. (2020) CAHOOTS. https://whitebirdclinic.org/what-is-cahoots/

[cl] STAR Program Evaluation. (2020). https://wp-denverite.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2021/02/STAR_Pilot_6_Month_Evaluation_FINAL-REPORT.pdf

[cli] Ibid.

[clii] McRae, J. (2021). STAR Program In Denver Expands To Respond To Calls Seven Days A Week. CBS Denver. https://denver.cbslocal.com/2021/08/31/star-program-mental-health-denver-police/

[cliii] Newark Community Street Team. (2021). What We Do. https://www.newarkcommunitystreetteam.org/what-we-do/ Note that homicide rates increased in 2021.

[cliv] Ibid.

[clv] Ibid.

[clvi] Newark Community Street Team Narrative Evaluation. (2020). Pg. 58 – 60. https://www.newarkcommunitystreetteam.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/NCST-Evaluation_FINAL.pdf

[clvii] Ibid.

[clviii] Ibid.