To read a PDF version of the full report, click here.

The infamous Florida butterfly ballot of 2000, which may have cost Al Gore the Presidency, highlights the dramatic consequences of bad ballot design for general election outcomes.[1] The design of primary election ballots can also have substantial consequences, as these elections determine which candidates advance to the general election. This research brief demonstrates how a unique ballot design has been helping shape electoral outcomes in New Jersey for more than two decades, shifting the power to decide who wins primary elections away from the voters and towards a small group of party insiders who control the candidate endorsement process.

New Jersey Primary Ballots

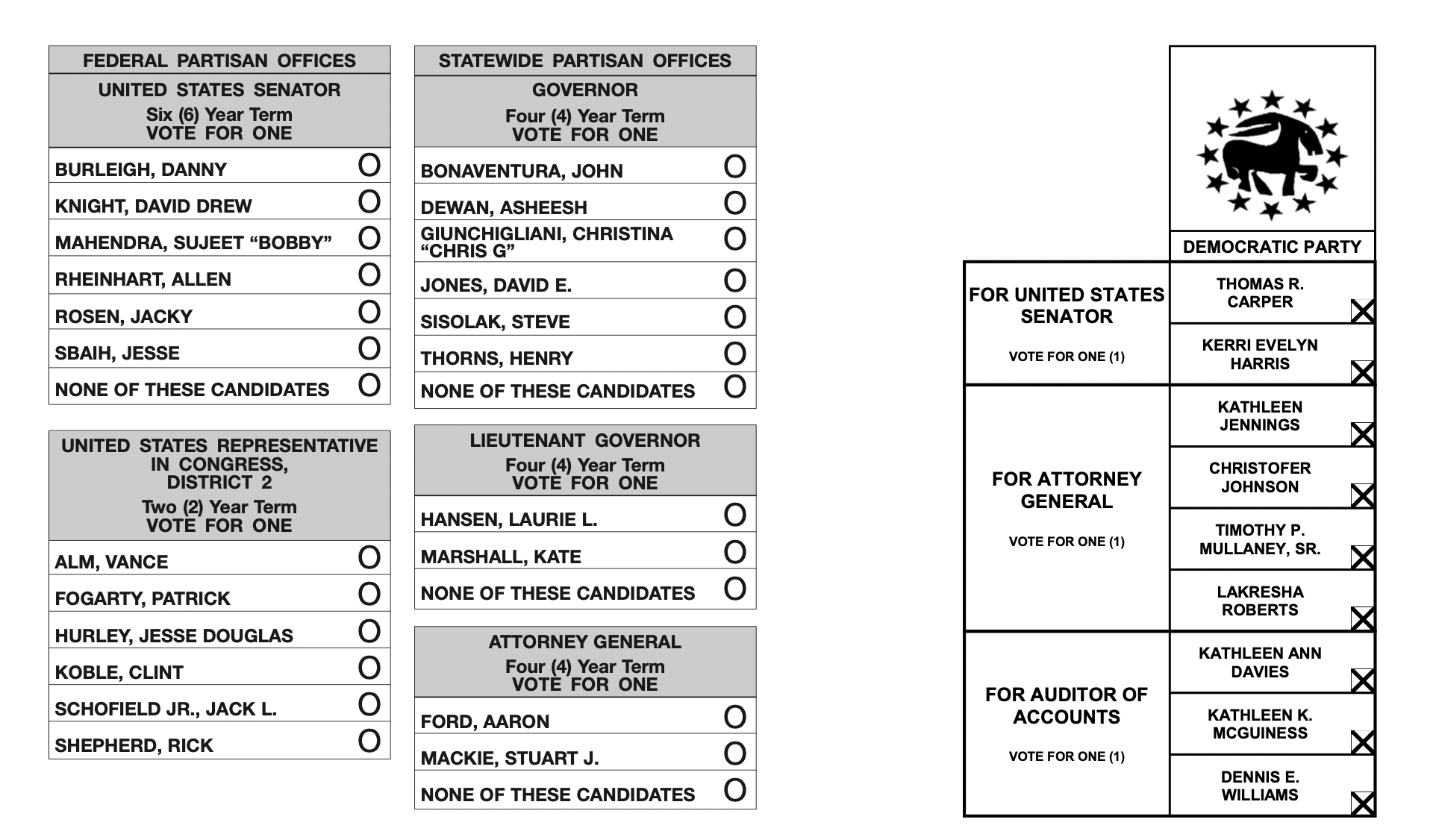

A review of primary ballots in all fifty states and the District of Columbia finds that New Jersey’s ballots look very different from those in other states.[2] In all other states and DC, primary ballots are organized by the electoral position being sought, with candidates listed beneath each position (see Figure 1, Elko County, Nevada ballot) or immediately to the right of each position (see Figure 1, Sussex County, Delaware ballot). These ballot designs make it easy for voters to identify which candidates are running for which electoral office.

By contrast, in nineteen of New Jersey’s twenty-one counties, the machine primary ballots used by the majority of voters are organized around a slate of candidates endorsed by either the Democratic or the Republican Party.[3] These slates of candidates are known as the “county line” or the “party line,” in reference to the fact that the endorsements are determined at the county party level and the endorsed candidates are presented on the ballot as a vertical or horizontal line of names. Candidates not on the line are placed in other columns or rows, sometimes far away from the county line candidates.

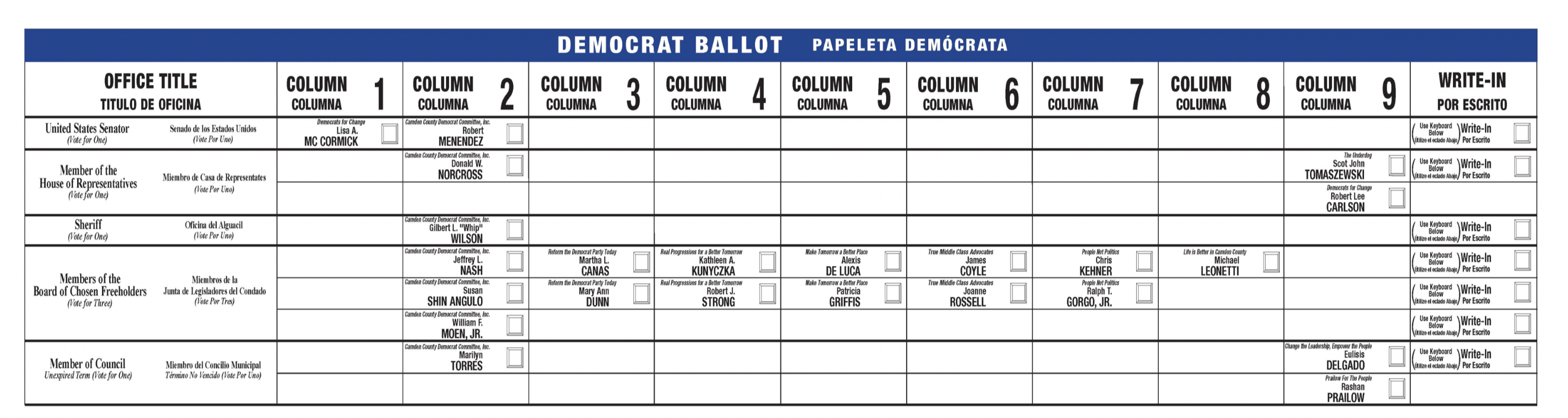

Figure 2 shows the 2018 New Jersey Democratic primary ballot from Camden County. The nine county line candidates are in column 2. The remaining fifteen candidates are scattered across the other eight, mostly empty, columns. There is no obvious logic as to why each of the non-endorsed candidates is in a particular column. Column 1 includes a single candidate for the U.S. Senate. Columns 3 through 8 include eleven candidates for Camden County Freeholder. Column 9 includes two candidates for the US House of Representatives and a candidate for the Camden City Council.

This ballot design — particularly listing candidates for the same office in different columns that may not even be adjacent, and candidates for different offices in the same column — makes it much more challenging for voters to determine which candidates are running for each office. Such a ballot design results in voters not realizing that some positions are contested or disqualifying their vote by mistakenly voting for too many candidates for a given position.[4] It also encourages voters to pick the candidates on the county line — an easy to find and visually consistent option. The county line is further advantaged by the placement of better-known candidates, such as those running for President, U.S. Senator, or Governor, at the top of the line and the inclusion of candidates for most or all of the offices on the ballot.[5] It is very challenging for candidates not endorsed by the party to compete with the county line by assembling a full slate of candidates that includes someone running for every position.

The county line is particularly advantageous for candidates whose names may be less familiar to voters, such as those running for the state legislature, and county-level or local positions. But the county line seems to provide a substantial electoral advantage regardless of the office being sought. A recent analysis by the Communications Workers of America found that no state legislative incumbent on the line had lost a primary election in New Jersey between 2009 and 2018.[6] Although incumbents generally win reelection, that advantage is rarely so absolute. In New York State, for example, twenty-two state legislative incumbents lost primary elections over the same time period.[7]

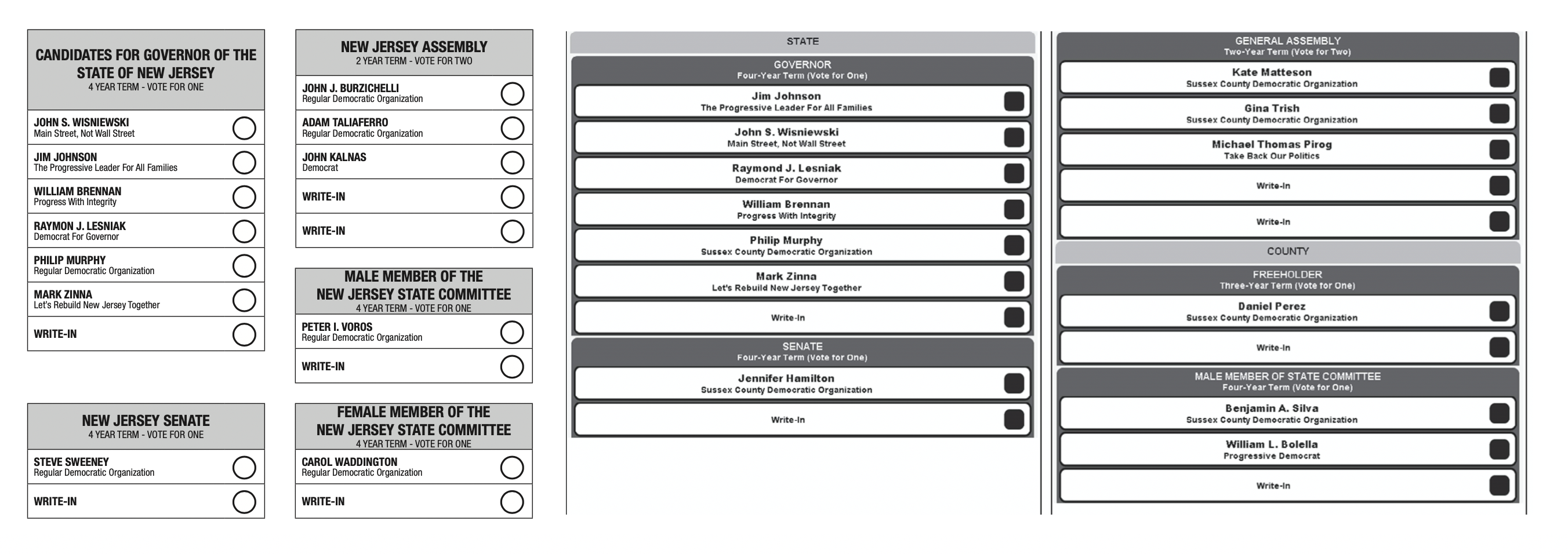

The line provides an advantage for non-incumbents as well. For example, in the 2017 Democratic primary for Governor, Phil Murphy was endorsed by all 21 county political parties. Murphy won the primary in 20 of those counties but lost Salem county to John Wisniewski. Wisniewski’s win of Salem County is the first time since 1997 that a candidate in a Democratic primary for Governor or U.S. Senator won any county without being part of the county line.[8] Salem is also one of only two New Jersey counties, along with Sussex, that do not organize their Democratic and Republican machine primary ballots around a county line. Instead, the County Clerks in those two counties structure their primary ballots around the electoral positions being sought, like ballots in every other state in the country.[9]

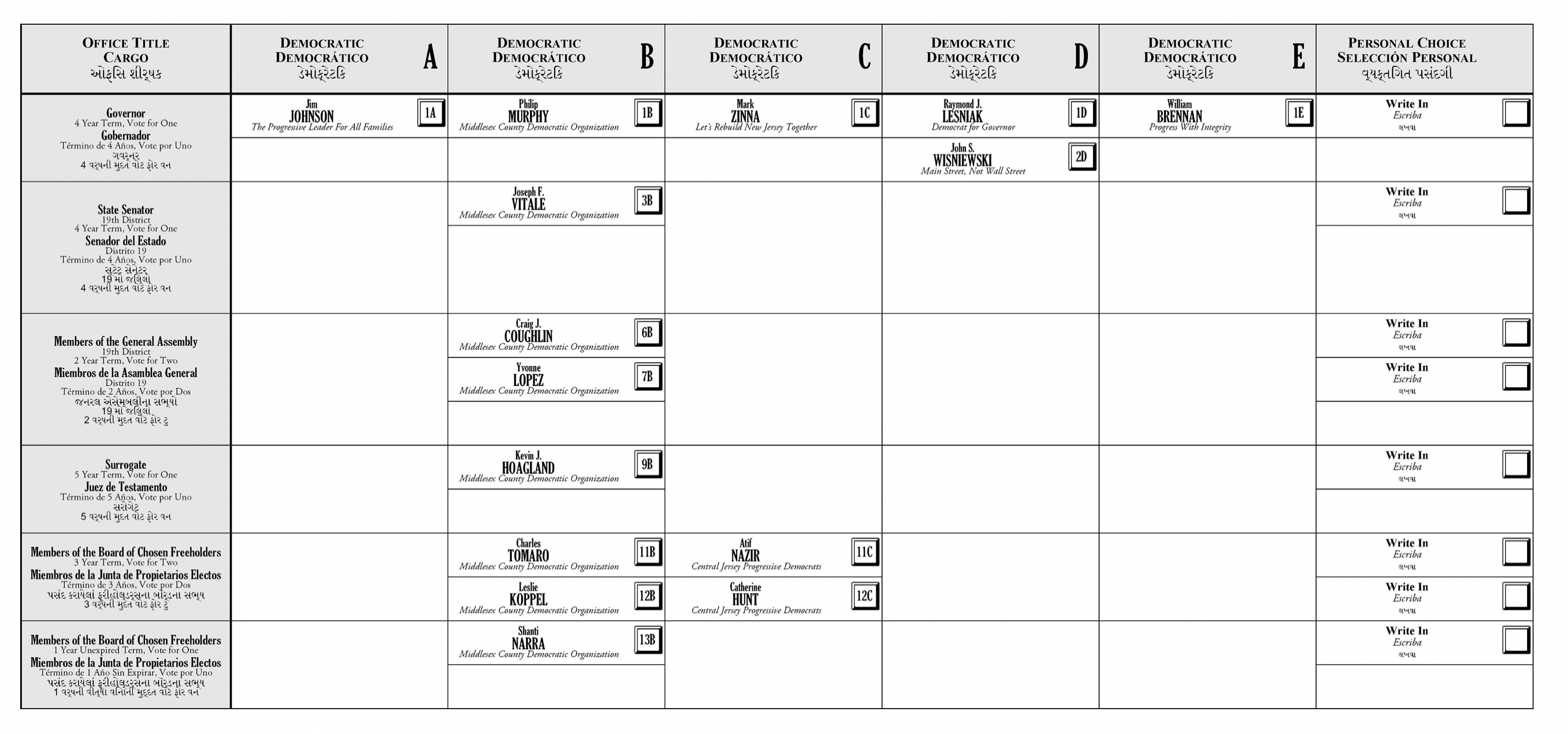

The difference between the Salem and Sussex primary ballots and those in the rest of the state is dramatic. Figure 3 shows the gubernatorial portions of New Jersey’s 2017 Democratic primary ballots for Salem and Sussex counties versus the Middlesex County ballot. The six candidates for Governor are clearly identified as such in the Salem and Sussex ballots. In contrast, the Middlesex ballot lists the names of the six gubernatorial candidates over five different columns, with one of the candidates – Wisniewski – in a separate row from the other five. It is not surprising that candidates without party endorsement have little chance of winning when their names are presented to voters in such a confusing manner.

Fair Primary Ballots for New Jersey

Problematic ballot design is frequently unintentional, the result of “overworked local officials who don’t have the time or staff to test whether a design works.”[10] When it comes to New Jersey primary ballots, however, faulty design is a feature rather than a bug. As detailed by Brett Pugach in a forthcoming Rutgers Law Review article, New Jersey’s primary ballot design reflects a combination of state laws and decades of court rulings that have created a confusing patchwork of regulations. The state’s county party organizations seem to have taken advantage[11] of this confusion to control the design of primary ballots, as a powerful means of benefitting the election of their chosen candidates.[12]

The New Jersey legislature could ensure that the state’s voters and not party insiders determine who wins primary elections by passing legislation that requires New Jersey primary ballots to be structured like those in other states. Those ballots would clearly indicate the title of each office being sought and, underneath or to the side of that, list the names of each candidate running for that office. To maximize ballot fairness, the candidates’ names would be randomly drawn and the order rotated by district, to counter the advantages of first-ballot position. Legislation that requires ballots organized in this manner ought to be a top reform priority for any legislators who care about election fairness.

End Notes

[1] Spenser Mestel (2018). How bad ballot design can sway the result of an election, The Guardian, November 19.

[2] The review included 2010 to 2020 primary ballots from at least four counties in every state and from the District of Columbia, as well as 2017 to 2020 primary ballots from all 21 New Jersey counties. See https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1vudVsxEcLvY2nZAfD_k88780nyh5sGCr?usp=sharing

[3] Some counties that use a county line for in-person machine voting ballots have used Vote-by-Mail paper ballots that are structured like ballots in other states, by the electoral positions being sought. In 2020, Hunterdon, Passaic, Salem, Sussex and Warren Counties are all using such Vote-by-Mail ballots for the Democratic and Republican primaries and Morris County is using such a ballot for the Republican primary. Historically, few New Jersey residents have voted by mail, so the impact of these ballots has been minimal. In 2020, however, the entire state is voting by mail, creating a natural experiment to assess the effect of the county line on voter behavior.

[4] Andrea Cordova McCadney, Lawrence Norden and Whitney Quesenbery (2020, February 3) Common Ballot Design Flaws and How to Fix Them, The Brennan Center. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/common-ballot-design-flaws-and-how-fix-them

[5] In years when there are no statewide or national contests, the candidates for State Senate or Assembly are placed at the top of the county line.

[6] Francisco Diez, The Likely Advantages of the Line, Communication Workers of America analysis, July 29, 2019.

[7] Diez

[8] Nick Acocella, 2017. How Much Does the Line Matter? InsiderNJ.com, June 10. https://www.insidernj.com/much-line-matter/

[9] Morris County does not organize its Republican primary ballot around the county line. However, the Democratic primary ballot in Morris County is organized around the county line.

[10] Danielle Kunits (2020, June 12) Don’t Let Mail-in Voting be thwarted by badly designed ballots. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/06/12/these-are-9-senate-seats-most-likely-flip/?

[11] Julia Sass Rubin (2020, June 26). Can Progressives Change New Jersey? The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/politics/can-progressives-change-new-jersey/

[12] Brett Pugach (forthcoming). The County Line: The Law and Politics of Ballot Positioning in New Jersey. Rutgers University Law Review.