Raising wages would help fight poverty and improve the well-being of workers & their families

To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

Raising New Jersey’s minimum wage to $15 an hour would reduce poverty while boosting the state’s economy by ensuring that more working people have more dollars to spend on essential goods and services. Unemployment has decreased significantly as New Jersey slowly emerges from the Great Recession, but wages have stagnated, and hardship and economic insecurity have increased. In other words, more people are working now but they aren’t earning enough to make ends meet for themselves or their families.

Gradually increasing the minimum wage to $15 by 2023 would boost wages for 1.2 million of the state’s 4.2 million workers and pump $4.5 billion in increased wages directly into the state’s economy. For the state to fully realize the many benefits of a stronger wage floor, it must include all workers, no matter who they are or the type of work they do.

Poverty Persists in an Uneven Economic Recovery; Raising Wages Would Help Ensure that Growth is More Broadly Shared

Low-income workers across high-cost New Jersey are not paid enough to reliably provide for themselves and their families. These low wages in turn depress our economy, dilute the quality and value of our jobs, and exacerbate poverty and inequality across the state.

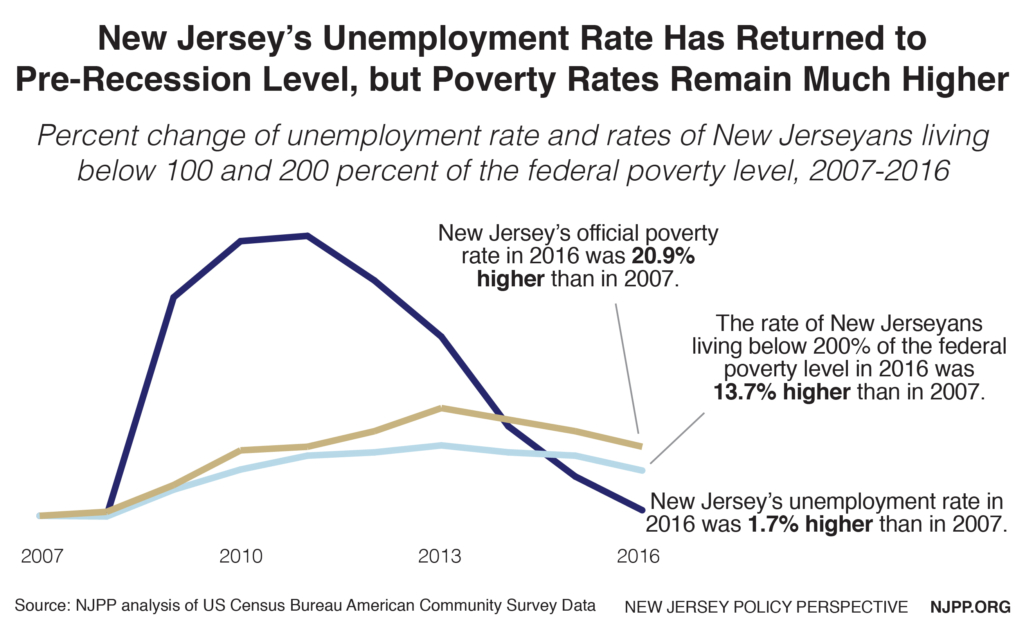

Many policymakers look to decreased unemployment as the key to shared prosperity – the idea being that the rising tide of fuller employment will lift all boats. But when basic worker standards like the wage floor fail to keep up with economic and productivity growth, we clearly see the limits of reduced unemployment in providing a pathway out of poverty.

While New Jersey’s unemployment rate fell by 45 percent – from 10.9 to 6 percent – from 2011 to 2016, the share of Garden State residents facing economic hardship did not follow suit; this metric barely budged. In fact, the share of New Jerseyans living below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (or $25,100 for a family of 4)[1] was the same in 2016 that it was in 2011: 10.4 percent, or approximately 900,000 people. And the share of New Jerseyans experiencing true hardship – living below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (or $50,200 for a family of 4) – decreased by just 4 percent from 2011 to 2016, falling from 24.7 percent to 23.8 percent, representing more than 2 million New Jerseyans.

Why has there has been significant reduction in unemployment but hardly any change in the share of struggling New Jerseyans? While drops in the poverty rate typically lag drops in unemployment, the facts remain: the poverty rate is far too high and too many hard-working New Jerseyans are not paid adequate wages for their work, in large part because the state’s minimum wage remains far below a survivable wage, never mind a living wage. Low-wage workers are not the only victims. Low wages and widespread hardship also hurts businesses and the state’s economy. How can anyone expect a robust economy when 1 in 4 workers have insufficient incomes? How can any business expect to thrive when so many would-be customers aren’t paid enough to purchase their products or services?

Of course, there are solutions that would help workers, reduce poverty and boost the economy. Chief among them is to gradually increase the state’s minimum wage to something more approaching a living wage. In 2016, the New Jersey legislature passed a bill to do just that, but Gov. Christie vetoed the measure.[2] Fortunately, the state’s new governor, Phil Murphy, made raising the wage to $15 an hour a core piece of his campaign platform. As the new administration and legislature move forward with this critical economic policy solution, it’s important to remember how widespread the need is and why such an increase would be a boon for New Jersey workers, families, businesses and the state’s economy at large.

Raising the minimum wage directly puts more money in the pockets of low-income workers who cannot meet their basic, everyday needs. With more take-home pay, these workers will spend that money immediately and locally on goods and services they were previously unable to afford. Essentially, their increased income is liquid, meaning that it is revolving through the economy instead of sitting stagnant in an investment account or stashed offshore, which is what typically happens when tax breaks are given to the wealthy.

Raising the Wage Would Have Positive Health and Social Effects, Too

Much of the conversation on increasing the wage focuses on the economic impact, but it is important to note the other positive effects that such a change would have on New Jersey workers and their families.

Academic research on the effects of the minimum wage shows that increases help lead to reductions in recidivism,[3] reductions in domestic violence and child abuse,[4] and reductions in teen pregnancy rates,[5] all of which – in addition to the positive effects of reducing poverty – have substantial benefits of improved public health and savings of taxpayer dollars.

On the flip side, scores of economic and health studies have shown a clear link between low incomes and serious health problems including diabetes, heart disease, arthritis and infant mortality.

There is a growing consensus that income is one of the most important determinants of health outcomes. Not only does the amount one is paid directly affect that person’s access to basic health needs (insurance, doctors, etc.), but as the American Public Health Association notes, income also shapes one’s access to other “social determinants of health, such as housing, education, and job opportunities.”[6]

New Jersey’s minimum wage of $8.60 an hour is a guaranteed poverty wage given the state’s high cost of living. Raising the wage to a survivable level that enables workers in low-income jobs to escape poverty will reduce the number of individuals reliant upon safety net programs – which frees up taxpayer dollars for use in other important areas – and lower the demand for various health services, helping to mitigate rising healthcare costs.[7]

Taken together, the long-term and far-reaching benefits of increasing the minimum wage to $15 will easily outweigh any of the costs or supposed negative impacts that its opponents broadcast when the idea is discussed.

Raising the Wage Would Benefit a Large & Diverse Group of Workers

The number of New Jersey workers who would benefit from a minimum wage increase to $15 an hour will depend on how quickly the increase is phased in.

The number of New Jersey workers who would benefit from a minimum wage increase to $15 an hour will depend on how quickly the increase is phased in.

For now, we assume that lawmakers would follow a similar (but not identical) phase-in schedule incorporated in the 2016 bill vetoed by Gov. Christie. For the sake of simplicity, we assume that the minimum wage would be increased to $10.10 an hour in the first step, on January 1, 2019, with four annual $1.25 increases to follow, bringing New Jersey’s minimum wage to $15.10 an hour by 2023.

This increase would equal a $4.5 billion raise for 1.2 million New Jersey workers, or 28 percent of the state’s workforce.

Of those workers, 865,000 – those who currently make less than $14.39 (the current-dollar equivalent of $15.10 in 2023) – would be directly affected by the increase and another 285,000 – those who earn slightly more than the new minimum and would likely see their pay also increase – would be indirectly affected.

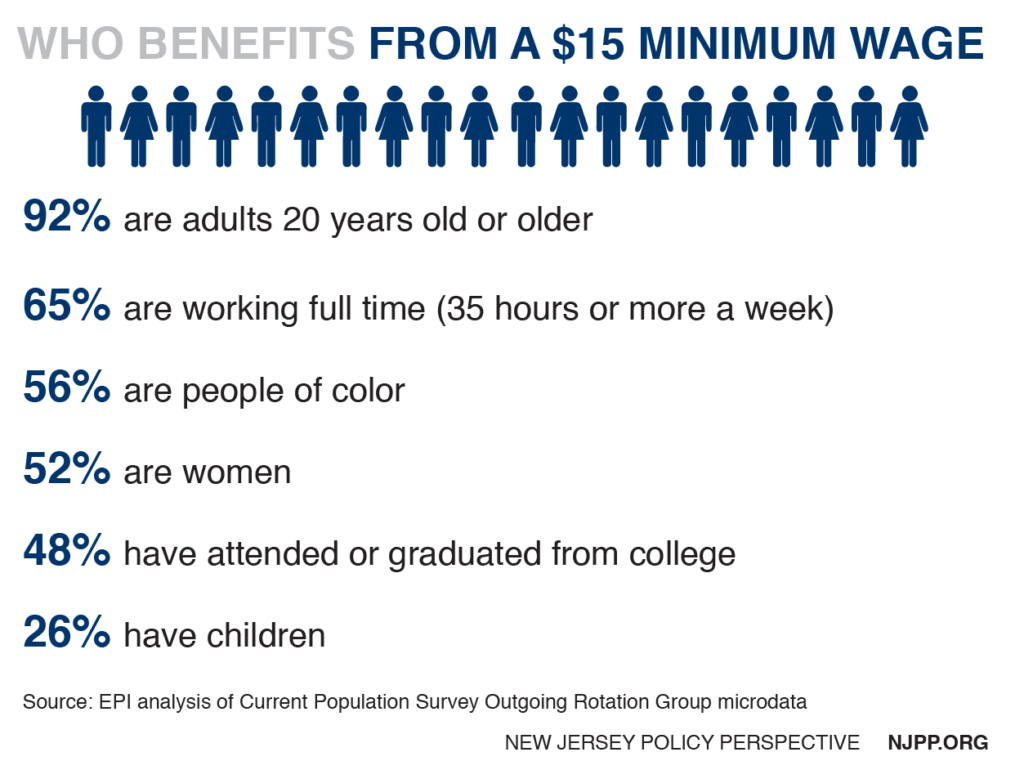

These workers are nearly all adults, most are working full time, many have pursued a higher education and they are raising an estimated 458,000 children.

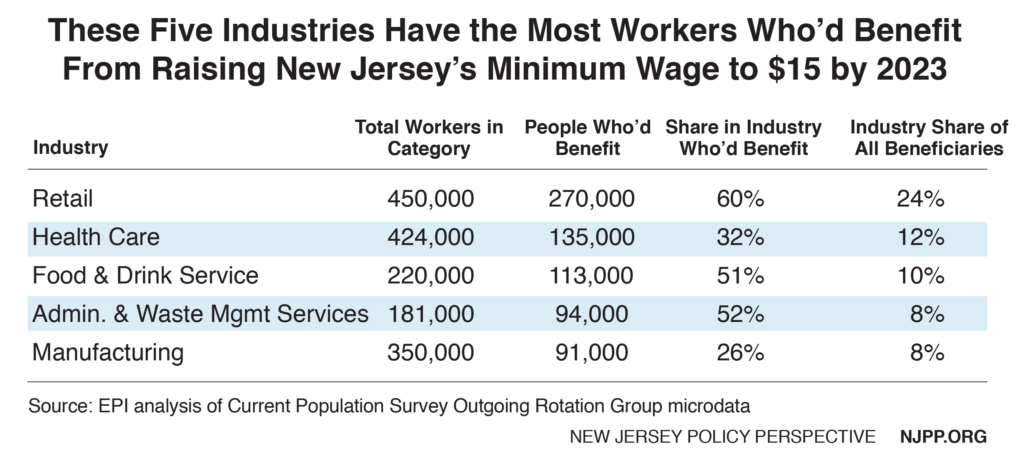

Most of the New Jersey workers who would benefit are in the retail, food service, and health care industries.

Today’s Minimum Wage Falls Short for New Jersey Working Families

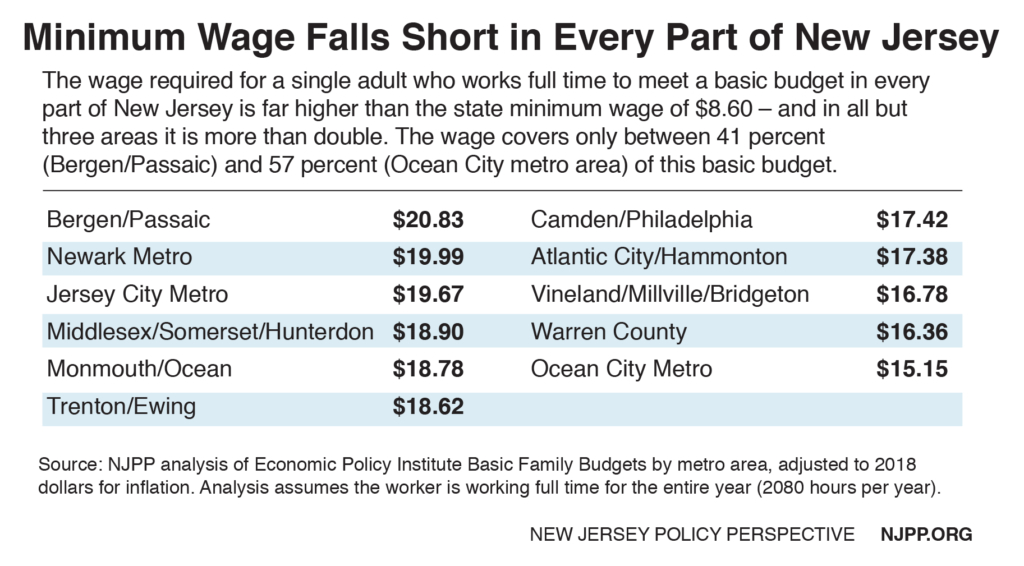

On January 1, 2018, New Jersey’s minimum wage rose 1.9 percent to $8.60 an hour. While this is higher than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour it is still a poverty wage in New Jersey. For example, a full-time minimum wage worker who doesn’t miss even one hour of work for the entire year will only earn $17,888.

A single New Jersey worker with no dependents cannot afford her basic needs on a wage less than $15 an hour. This is true in every region of the state.

The Economic Policy Institute’s family budget tool estimates what it takes to maintain a basic budget that accounts for major expenses – housing, food, transportation, health care, child care and taxes – and a modest amount for other necessities like clothing, household supplies, and entertainment. This proposed budget does not include money for other typical expenditures like modest weekend trips or savings.

In the least expensive part of the state, the Ocean City metro area, a single adult would have to earn $15.15 an hour – $31,512 per year – to afford this basic budget; in the most expensive part of the state, the Bergen and Passaic metro area, a single adult would have to earn $20.83 an hour – $42,243 per year – to afford the same.

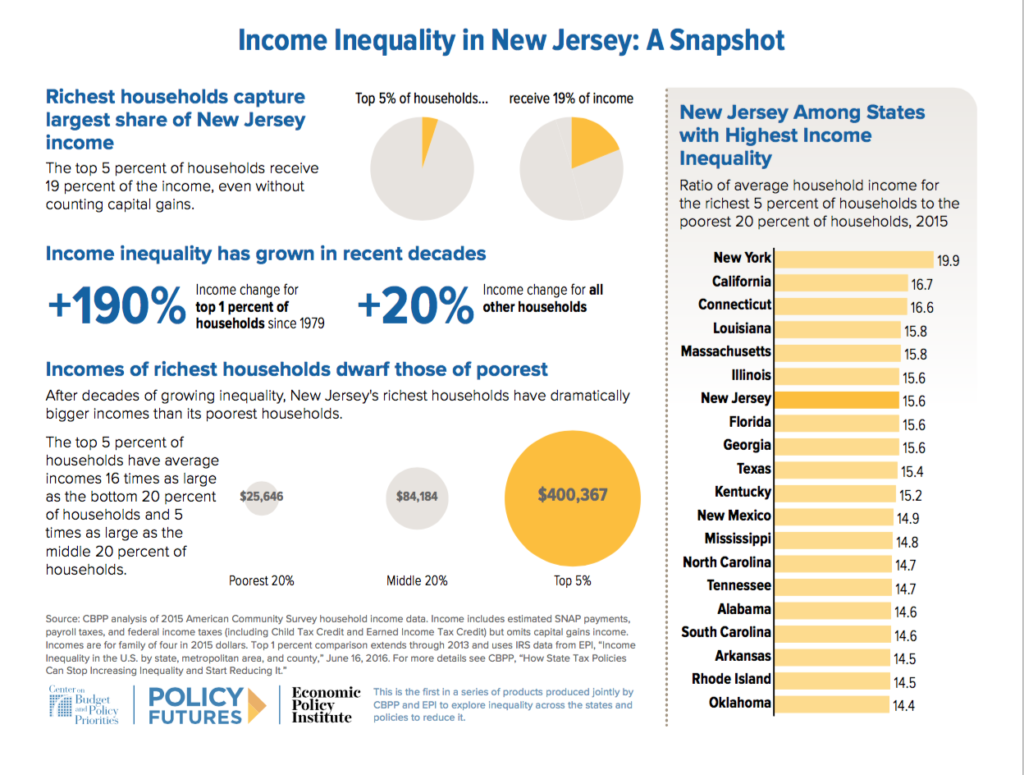

Meanwhile, the income gap between New Jersey’s very wealthy residents and the rest of us – particularly the poorest residents – persists and is growing. New Jersey now ranks 7th in the nation in income inequality, with the top 5 percent of households having average incomes 15.6 times higher than the bottom 20 percent of households. This inequality has intensified in recent decades: between 1979 and 2013, incomes for the wealthiest 1 percent of New Jersey households grew by 190 percent – a rate 9.5 times higher than the income growth for the bottom 99 percent.[8]

Low wages not only pose a danger to workers and our economy, they also result in the expenditure of taxpayer dollars to support programs that too many low-paid workers need to get by. New Jersey spends an estimated $726 million a year on basic safety net programs for working families. This cost estimate is a significant undercount, since it includes Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) but not the state’s share of the Earned Income Tax Credit, the tax credit for working families who aren’t paid enough to make ends meet.[9]

While a robust safety net is important to assist all families who have fallen on hard times, the state has a critical role to play in ensuring that these programs aren’t subsidizing profitable corporations that are paying poverty wages. In a state with significant budget problems, $726 million is a serious amount of money that could be spent on other priorities and public services.

Tipped Workers Deserve A Raise Too

Recent conversations around raising the minimum wage in New Jersey have left out some of the state’s lowest-paid and most vulnerable workers: those who rely on tips.[10] These workers must be included in any minimum wage increase.

Currently, New Jersey’s wage floor for tipped workers is tied to the federal tipped minimum wage: $2.13 an hour. If a worker doesn’t make the $6.47 in tips necessary to bring them to the state’s $8.60 an hour minimum wage, their employer is required to make up the shortfall – this is called a “tip credit.” Unfortunately, asking for the difference falls to workers, many of whom may feel like their jobs are at risk if they speak up. Not surprisingly, there is significant evidence to show that tipped workers suffer from higher rates of wage theft than other workers.[11]

Additionally, recent action by the Trump administration has made wage theft even more likely. In December 2017, the Department of Labor proposed a rule that would allow restaurant owners to legally take the tips earned by their workers as long as those workers earn the minimum wage – a move that could lead to New Jersey’s tipped workers losing $120 million every year.[12]

The median wage of American tipped workers is $10.22 an hour, compared to $16.48 an hour for the general workforce.[13] Tipped workers are more likely to be women (66.6 percent of tipped workers vs. 48.3 percent of the total workforce) and people of color (38.5 percent of tipped workers vs. 33.9 percent of the total workforce). And the women who work for tips make less, with a median wage of $10.07 an hour compared to $10.63 an hour for male tipped workers.[14]

New Jersey should do away with the tipped wage altogether. This two-tiered wage system has been around since 1966, when amendments to the Fair Labor Standards Act introduced a “subminimum wage” for workers who receive tips. Seven states – Alaska, California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington – do not have a subminimum wage for tipped workers. Another 31 states, plus the District of Columbia, have tipped minimum wages that are above the federal level of $2.13 an hour.

When increasing the minimum wage, lawmakers must address New Jersey’s tipped wage – if not by eliminating it, at least by raising it to a higher share of the minimum wage.

Failing to act would create a $12.87 gap that employers are theoretically expected to make up for their tipped workers, nearly double what the current gap is. Seven other states have shown that having a separate and lower wage for tipped workers is unnecessary, and doing away with it would simplify labor regulations, mitigate income inequality, and bolster the state’s economy by helping more workers move closer to a livable wage.

Misleading Myths About Wage Increases & Job Losses

When lawmakers work to increase the minimum wage, opponents line up to say doing so would hurt the economy and lead to a significant loss of jobs. These claims are as old as wage increases themselves, but decades of real-world experience show that they are false.

In fact, the overwhelming majority of rigorous research shows that increasing the minimum wage increase the earnings of workers with little to no adverse impact on employment.[15]

An exhaustive report by the National Employment Law Project in 2016 looked at the effects of federal minimum wage increases over the past 70 years and found that, even for industries which are most affected by higher minimum wages, there was no correlation between those increases and lower levels of employment.[16] And two recent meta-studies – “studies of studies” that pooled the results of 91 separate analyses – have similarly found essentially no employment effects from minimum wage increases.[17]

And New Jersey’s own history belies opposition claims of economic harm – the last time the state increased the minimum wage through the ballot in 2013 from $7.25 to $8.25, opponents claimed we would lose 30,000 jobs;[18] instead, we gained 90,000.[19]

The Seattle Situation

Seattle implemented a phased-in minimum wage increase starting in April of 2015 that reached $15 for large employers – those with more than 500 employees – this year and will reach that level for small employers between 2019 and 2021 depending on whether they pay toward their workers’ health benefits.[20]

A recent and widely cited University of Washington study claimed that Seattle’s minimum wage increase resulted in a significant loss of jobs, leading some to suggest that $15 an hour – even in a thriving and high-cost economy like Seattle’s – was simply too high of a minimum wage. But the study’s methodology has raised a lot of questions and critiques from economists and researchers,[21] [22] [23] [24] including:

- The study was limited to single-site establishments, excluding workers at multi-site chains such as Starbucks or Walmart where positive effects of minimum wage increases are often realized, and leaving out 40 percent of the city’s workforce;

- By excluding workers employed by multi-site chains, the study incorrectly counted a worker who left a job at a small business for a job at a larger company as a job loss;

- The study focused on jobs that pay $19 or less, assuming that a reduction of jobs in that bracket equaled a loss of opportunity for workers and counted as lost jobs, when instead it should have recognized that many jobs that were formerly in that pay range have seen a wage increase raising them above it;

- The study used other cities in Washington state as a control for its experiment with Seattle, instead of using other cities from around the country that are similar to Seattle in important characteristics like size, population, and economic activity – as other more reliable studies have done.

It is also notable that the study’s findings are not in line with the large amount of research related to minimum wage increases – even the research that has found job losses.

The UW study also flies in the face of how Seattle’s economy has actually performed since it began phasing in its minimum wage increase. While the unemployment rate has varied but remained largely the same since the ordinance took effect in 2015, the city’s poverty rate has dropped from 14.4 percent in 2014 – the year before the minimum wage ordinance took effect – to 11.5 percent in 2016. That represents an estimated 14,708 fewer people in poverty just within Seattle alone, a fact made even more remarkable when you consider that the city’s population has grown by 36,389 people over the same period of time.[25]

One of the primary points of opposition to Seattle’s minimum wage increase was that it would lead to widespread restaurant closings. Tom Douglas, a notable restaurateur who owned 15 restaurants in Seattle at the time, predicted that he would “lose maybe a quarter” of his restaurants in the city.[26] But, just like many of the other predictions made by opponents, such doom and gloom has not materialized. Instead, the opposite has occurred: more restaurants have opened in Seattle than previous years.[27] Douglas himself has contributed to this trend, having opened more restaurants and recanted his previous prediction.

Another claim of opponents is that raising the minimum wage will lead to drastic price increases for food and groceries. In 2014, prior to the implementation of the wage increase, the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce released a survey, revealing that 50 percent of participating companies believed they would need to “increase prices to offset a $15 minimum wage.”[28] Once again, this concern by-and-large has not been realized.

A 2017 study by the University of Washington School of Public Health looked at grocery store prices from the month before the wage increase took effect to two years after it began and found no significant change.[29] “There is no evidence of change in supermarket food prices by market basket or increase in prices by food group in response to the implementation of Seattle’s minimum wage ordinance,” it concludes.[30]

Despite what many opponents want lawmakers and the public to believe, Seattle’s economy has continued to grow while its minimum wage has risen. The many predictions of lost jobs, shuttered restaurants, increased food prices, and all around economic disaster never came to fruition – not even close.

Low Wages & Income Inequality Are Damaging New Jersey

The rising dangers of poverty and its closely linked partner of income inequality pose a serious danger not just to New Jersey, but the country at large. The High Commissioner for Human Rights at the United Nations recently finished an investigation into extreme poverty in the United States. The report’s findings should give pause to all those who believe in a strong and prosperous nation.[31]

“The American Dream is rapidly becoming the American Illusion, as the United States now has the lowest rate of social mobility of any of the rich countries,” the report reads. The report is exhaustive in its detail and historical context, painting a dispiriting picture of the nation’s economic landscape and the damage it wrecks on such a large portion of the population. Unsurprisingly, many of the hardships described show their hallmarks here in the Garden State through rising inequality and deep poverty, and they grow more conspicuous by the day.

New Jerseyans continue to struggle to make ends meet in an economy where whatever gains that have been made since the Great Recession have gone to the already wealthy. Poverty is stubbornly high, and income inequality poses a great threat to our economy and society. Taken together, the arguments against raising the minimum wage ring hollow in contrast to the threats we face if we fail to act. Raising the minimum wage is an absolute necessity to strengthen New Jersey’s economy and spread prosperity to every worker, family, and business in this state.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used To Determine Financial Eligibility For Certain Federal Programs, 2018. https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

[2] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Gov. Christie Rejects Pay Boost for Nearly 1 Million Workers, August 2016. https://www.njpp.org/blog/gov-christie-rejects-pay-boost-for-nearly-1-million-new-jerseyans

[3] Agan, A. Y. and Makowsky, M. D., The Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism, January 2018. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3097203

[4] Raissian, K. M., Bullinger, L. R., Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates?, January 2017. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916303139?via%3Dihub#!

[5] Bullinger, L. R., The Effect of Minimum Wages on Adolescent Fertility: A Nationwide Analysis, March 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28103069

[6] American Public Health Association, Improving Health by Increasing the Minimum Wage, November 2016. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2017/01/18/improving-health-by-increasing-minimum-wage

[7] Economic Policy Institute, Raising the minimum wage could improve public health, July 2016. http://www.epi.org/blog/raising-the-minimum-wage-could-improve-public-health/

[8] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, How State Tax Policies Can Stop Increasing Inequality and Start Reducing It, December 2016. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/how-state-tax-policies-can-stop-increasing-inequality-and-start

[9] UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, The High Public Cost of Low Wages, April 2015. http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/pdf/2015/the-high-public-cost-of-low-wages.pdf

[10] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Raising the Tipped Minimum Wage Would Increase the Economic Security of Many Hard-Working New Jerseyans, July 2014. https://www.njpp.org/reports/raising-the-tipped-minimum-wage-would-increase-the-economic-security-of-many-hard-working-new-jerseyans

[11] Economic Policy Institute, Employers steal billions from workers’ paychecks each year, May 2017. http://www.epi.org/publication/employers-steal-billions-from-workers-paychecks-each-year-survey-data-show-millions-of-workers-are-paid-less-than-the-minimum-wage-at-significant-cost-to-taxpayers-and-state-economies/

[12] Economic Policy Institute, Employers would pocket $5.8 billion of workers’ tips under Trump administration’s proposed ‘tip stealing’ rule, December 2017. http://www.epi.org/publication/employers-would-pocket-workers-tips-under-trump-administrations-proposed-tip-stealing-rule/

[13] Economic Policy Institute, Twenty-Three Years and Still Waiting for Change, July 2014. https://www.epi.org/publication/waiting-for-change-tipped-minimum-wage/

[14] Ibid. XXIV

[15] Business for a Fair Minimum Wage, Research Shows Minimum Wage Increases Do Not Cause Job Loss, 2018. https://www.businessforafairminimumwage.org/news/00135/research-shows-minimum-wage-increases-do-not-cause-job-loss

[16] National Employment Law Project, Raise Wages, Kill Jobs? Seven Decades of Historical Data Find No Correlation Between Minimum Wage Increases and Employment Levels, May 2016. http://www.nelp.org/publication/raise-wages-kill-jobs-no-correlation-minimum-wage-increases-employment-levels/

[17] See pages 4-6 in Center for Economic and Policy Research, Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?, February 2013. http://cepr.net/documents/publications/min-wage-2013-02.pdf

[18] Watchdog, New Jersey’s minimum-wage question poses maximum complexity, October 2013. https://www.watchdog.org/new_jersey/new-jersey-s-minimum-wage-question-poses-maximum-complexity/article_3e1f3a4a-a943-549c-8568-e5639189b72d.html

[19] NJPP analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. State and Area Employment, Hours, and Earnings, New Jersey, Total Non-Farm, 2013-2015.

[20] Office of Seattle Mayor Edward B. Murray, $15 Minimum Wage. http://murray.seattle.gov/minimumwage/

[21] The Washington Post, Seattle’s higher minimum wage is actually working just fine, June 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/posteverything/wp/2017/06/27/seattles-higher-minimum-wage-is-actually-working-just-fine/?utm_term=.f2b59cb4e742

[22] Economic Policy Institute, The “high road” Seattle labor market and the effect of the minimum wage increase, June 2017. http://www.epi.org/publication/the-high-road-seattle-labor-market-and-the-effects-of-the-minimum-wage-increase-data-limitations-and-methodological-problems-bias-new-analysis-of-seattles-minimum-wage-incr/

[23] Economic Opportunity Institute, A tale of two studies: poor research leads to poor findings on minimum wage, June 2017. http://www.eoionline.org/blog/a-tale-of-two-studies/

[24] On the Economy – A Jared Bernstein Blog, That Seattle minimum wage study has some curious results, June 2017. http://jaredbernsteinblog.com/that-seattle-minimum-wage-study-has-some-curious-results/

[25] NJPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 – 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates

[26] The Stranger, Tom Douglas Talks About How a $15 Minimum Wage Would Affect His Restaurants, March 2014. https://www.thestranger.com/slog/archives/2014/03/11/tom-douglas-talks-about-how-a-15-minimum-wage-would-affect-his-restaurants

[27] Puget Sound Business Journal, Apocalypse Not: $15 and the cuts that never came, October 2015. https://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/print-edition/2015/10/23/apocolypse-not-15-and-the-cuts-that-never-came.html

[28] Washington Policy Center, Seattle Employers Warn $15 Minimum Wage Will Come With a Hefty Price Tag, April 2014. https://www.washingtonpolicy.org/publications/detail/seattle-employers-warn-15-minimum-wage-will-come-with-a-hefty-price-tag

[29] UW Medicine, Seattle’s minimum-wage hike didn’t boost supermarket prices, September 2017. https://newsroom.uw.edu/news/seattle%E2%80%99s-minimum-wage-hike-didnt-boost-supermarket-prices

[30] International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, The Impact of a City-Level Minimum-Wage Policy on Supermarket Food Prices in Seattle-King County, September 2017. http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/14/9/1039