Health coverage for all New Jerseyans is essential for protecting public health, especially during a global health crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic — along with the ongoing attempts by the outgoing Trump Administration to derail the Affordable Care Act (ACA) — have put all residents at risk. In an important move towards building a health system that better addresses the needs of New Jersey residents, the state opened its own state-based health exchange (SBE) on November 1, 2020.

The state-based exchange will help to increase access to, and affordability of, health insurance, particularly for low-income residents who, due to decades of discriminatory policies, are disproportionately Black and Latinx. By improving the state’s ability to address racial equity in health and meet the demands of an increasingly expensive health care landscape, the exchange promises to increase coverage rates and better protect public health in the Garden State. This explainer answers frequently asked questions about this new state-based health exchange.

- What is a state-based health exchange?

- How does the state-based exchange improve coverage options for New Jersey residents?

- How is New Jersey’s new exchange different from the old exchange?

- Who will benefit from coverage through the state-based exchange?

- Who can buy coverage on a state-based exchange?

- What other options do New Jerseyans have to enroll in health insurance coverage?

- How can state lawmakers further strengthen the state exchange?

What is a state-based health exchange (SBE)?

A state-based health exchange (SBE) is a platform that offers residents health insurance coverage options while promoting competition among insurance companies, which can lower costs.[1] For residents of New Jersey, the SBE will take the place of the federal Marketplace, HealthCare.gov. This new “Marketplace” allows individuals and families to compare and purchase coverage plans that best support their needs.[2] It also allows those who qualify to get financial support for health insurance from the state or federal government.[3] New Jersey’s new SBE opened for enrollment on November 1, 2020; the enrollment period is open until January 31, 2021.

The advantage of a SBE over the federal HealthCare.gov exchange is that the state controls all aspects of the Marketplace, from creating and managing its own website for the exchange, to advertising, setting the enrollment period, and determining eligibility for financial support. These moves should also help make coverage more affordable, allow for greater engagement with potential enrollees, and make the system easier to use.

With a SBE, the state is able to tailor the exchange to the unique needs of New Jersey residents, particularly for low-income communities and people of color who have struggled to enroll or afford coverage in previous years. Other states’ experiences with SBEs have shown that, with adequate funding and personnel support, SBEs can better offer personalized assistance and build confidence in the exchange. They can help people feel better protected from the risks of information sharing with federal agencies during times of uncertainty and attacks on immigrant populations from the federal government.[4] In using these strategies, SBEs in other states have successfully reduced their uninsured rates and seen higher rates of insurance amongst younger enrollees.[5]

For the 2021 plan year, New Jersey joins 13 states and the District of Columbia with SBEs, including a number of regional neighbors, such as Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, and Maryland.[6]

How does the state-based exchange improve coverage options for New Jersey residents?

Beginning with the 2021 plan year, New Jersey is offering expanded support and financial assistance to make it easier for residents to enroll in coverage. With continued focus on these efforts, the state can continue to improve health care access and affordability for all Garden State residents.

The new SBE will improve health coverage options by:

Expanding the Enrollment Period

New Jersey residents will have double the amount of time to shop for an insurance plan on the exchange compared to people in states using the federal exchange.[7] The state’s enrollment period this year runs from November 1, 2020 through January 31, 2021.[8] This extended opportunity to enroll in coverage will give residents more time to explore their options and choose an appropriate option that best fits their needs. For coverage that begins on January 1, 2021, residents must sign up by December 31, 2020.[9]

Providing Additional Navigator Program Assistance

The Navigator program is a part of the ACA that is designed to help people learn about the exchange and enroll in a plan appropriate for them. Navigators act as liaisons within communities, helping residents understand the exchange website, explore their plan options, and complete eligibility and enrollment forms. Navigators have been shown to be effective in increasing insurance coverage rates and successfully connecting diverse populations.[10]

Over the years, federal funding for the Navigator program has been drastically cut, hurting access and enrollment.[11]Once a state adopts a SBE, it is responsible for funding the program, allowing for greater investment even when federal funding is cut. With the New Jersey state exchange, the state dedicated $3.5 million for 16 organizations across the state to serve as Navigators for the 2021 plan year.[12] This is an increase of $1.5 million over the amount that the state dedicated for the 2020 plan year and is about nine times greater than the $400,000 that New Jersey received when still using a federally-facilitated exchange for the 2019 plan year.[13] The increased funding will be essential to the exchange’s success and to increasing coverage for residents across the state.

Providing Additional Financial Assistance

With the passage of the state exchange in July 2020, New Jersey replaced the recently repealed federal health insurance assessment with one at the state level.[14] This fee on health insurance companies provides funding for a new state-level subsidy on the SBE.[15] This means that, in addition to the federal financial assistance provided through the exchange (known as the Advanced Premium Tax Credit, or APTC), enrollees with incomes below 400 percent of the federal poverty level may also receive additional assistance with their monthly payments.

Keeping Costs Under Control

States that run their own SBEs are better able to curb premium increases and control costs for their enrollees.[16] Having also established a reinsurance program — which provides payments to health insurers to help mitigate the costs of large claims — additional state subsidies, and regulation of short-term plans, New Jersey can better improve cost control with the SBE and further dampen rising prices for coverage.[17] Without having to pay the user fees for utilizing the federal platform and by shifting the exchange to a more uniquely New Jersey consumer-oriented approach, there remains an opportunity for further improvements in the Marketplace mirroring those seen in other states with SBEs.[18]

How is New Jersey’s new exchange different from the old exchange?

From 2014 to 2019, New Jersey used a federally-facilitated exchange (FFE).[19] Under a FFE, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) handles all Marketplace functions — such as advertising, certifying health plans that meet the required standards for guaranteed coverage (including covering women’s preventative health care, like mammograms), managing enrollment, and determining eligibility — through HealthCare.gov. When using this option, the federal government also collects user fees from states for their services in running HealthCare.gov and managing the Marketplace.[20] Essentially, the Garden State relied on the federal government to provide “one-size-fits-all” health coverage options.

For the 2020 plan year, New Jersey then transitioned to a state-based exchange on a federal platform (SBE-FP) before fully transitioning to a SBE. Under a SBE-FP, the state government manages Marketplace functions except for eligibility determination and enrollment, which is still done through the HealthCare.gov platform by HHS. The federal government continued to collect user fees for these services.

From the 2021 plan year forward, New Jersey is using a SBE, which does not require user fees paid to the federal government because it does not use the HealthCare.gov platform. Overall, for the 2021 plan year, 30 states are using federally-facilitated exchanges, 6 states are using SBE-FPs, and 14 states are using SBEs.[21]

Who will benefit from coverage through the state-based exchange?

There are hundreds of thousands of uninsured New Jersey residents who stand to benefit from a SBE.[22] Most of these residents are likely eligible for health coverage plans under the SBE, as well as for the new financial assistance programs in the SBE.[23]

With additional financial support opportunities through new state subsidies, increased funding for the Navigator program which helps people understand their options and enroll, an extended enrollment period, and future options for expanding eligibility, the SBE will be more accessible than New Jersey’s previous exchanges for residents with low incomes and those who may need additional outreach to help them know about and understand the exchange.

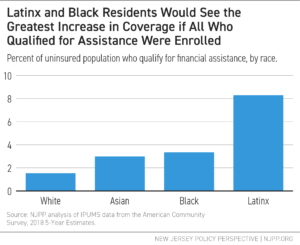

Black and Latinx residents, as well as young adults, make up the largest number of people who may currently be eligible for Marketplace coverage but who have not obtained coverage through the earlier exchanges. This may be due to a lack of knowledge about the exchange or due to inability to afford coverage even after federal financial assistance. Given the expanded benefits of the SBE that will help to address these issues, people of color with low incomes in New Jersey will see the greatest benefits and have the greatest potential for increases in coverage as a group. Additionally, residents who have enrolled in coverage through the exchanges in previous years will gain access to the new state financial assistance and the extended enrollment period.

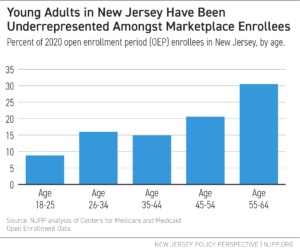

During the 2020 plan year’s Open Enrollment Period (OEP), about 246,400 individuals purchased plans on the state exchange through the federal platform (SBE-FP) that New Jersey utilized at that time. Of those enrolling in plans, the majority of people were between the ages of 45 and 64, and white. This indicates an ineffectiveness of previous exchange types to enroll younger working adults, a key demographic that is often more difficult to get covered due to cost barriers and perceptions of not “needing” coverage.[24] In 2019, over 390,000, or over 56 percent of the uninsured population, were adults between the ages 19 and 44.[25] With only 40 percent of the enrollees in last year’s exchange representing these age groups, there remains a need for further affordability, outreach, and enrollment efforts.

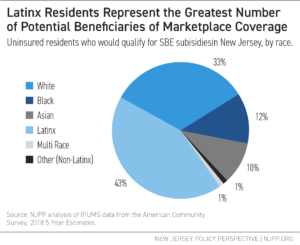

Also worryingly, Black residents were noticeably underrepresented in previous exchanges, only making up 5 percent of enrollees during the 2020 plan year Open Enrollment Period, while representing 16 percent of New Jersey’s uninsured population. Similarly, Latinx residents are underrepresented, making up only 14 percent of enrollees while representing nearly 50 percent of New Jersey’s uninsured population. While some of the uninsured may be undocumented or qualify for other programs, like NJ FamilyCare, the low rates of enrollment indicate a need for improvement in outreach efforts for communities of color.

Further, people with low incomes would benefit from the exchange, as many who are uninsured will qualify for subsidized coverage. In 2019, approximately 68 percent of uninsured individuals in New Jersey had incomes that qualified them for subsidies (between 139% and 400% FPL, or between $17,609 and $51,040 for an individual, and between $29,974 and $86,880 for a family of three).[26] Latinx residents are the most represented amongst this group. Based only on income eligibility among uninsured residents (notably, not considering documented status), people of color, and particularly Latinx residents, would see the largest increases in coverage if all who qualified enrolled through the exchange.

Further, people with low-incomes would benefit from the exchange, as many who are uninsured will qualify for subsidized coverage. In 2019, approximately 68 percent of uninsured individuals in New Jersey had incomes that qualified them for subsidies (between 139% and 400% FPL, or between $17,609 and $51,040 for an individual, and between $29,974 and $86,880 for a family of three).[27] Latinx residents are the most represented amongst this group. Based only on income eligibility among uninsured residents (notably, not considering documented status), people of color, and particularly Latinx residents, would see the largest increases in coverage if all who qualified enrolled through the exchange.

Who can buy coverage on a state-based exchange?

Currently, in order to buy insurance on the SBE, a person must be a U.S. citizen, a national with primary residence in New Jersey, or a documented immigrant for the entire time covered by the health insurance plan.[28] Incarcerated individuals and residents with affordable health insurance coverage available through other means, such as through employment, a spouse’s employment, Medicare, Medicaid, or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), cannot purchase coverage through the SBE.[29]

While undocumented residents cannot purchase coverage through the exchange, certain members of a mixed status household can; this means that, in mixed status households where members have different immigration or citizenship status, a child or spouse may be eligible to enroll even when one or both parents or other members cannot because they have other coverage or are undocumented.[30]

A state does have the power to submit waivers to the federal government to expand eligibility to undocumented residents within the state’s exchange. These waivers are known as 1332 State Innovation Waivers, and they have to be approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to take effect. New Jersey does not currently have this in place, but will have the option to submit waiver applications for this purpose in future plan years.

What other options do New Jerseyans have to enroll in health insurance coverage?

The exchange website provides information about eligibility not only for potential financial assistance on the exchange, but also for the state’s other health insurance programs outside the exchange, including NJ FamilyCare, the state’s Medicaid program.

In order to check eligibility for financial support on the exchange, New Jersey residents can visit GetCoveredNJ (https://nj.gov/getcoverednj/). On the site, consumers can compare potential financial assistance by entering information such as ZIP code, birthdate, income, and information on spouses or dependents. If a person is determined to be eligible to purchase a plan, they can then complete a full application and browse the options for purchase. These options provide information on coverage and final monthly cost after federal and state financial assistance has been taken into account. A plan for 2021 must be purchased by January 31, but Special Enrollment Periods (SEPs) — or times at which a person may become eligible to purchase during the year due to changes in employment and other reasons for loss of coverage — are available throughout the year.

In addition to the plans and subsidies offered on the SBE, New Jersey residents may qualify for NJ FamilyCare (http://www.njfamilycare.org/). This program has served as an important buffer during the COVID-19 pandemic for many who lost employer-based coverage during the public health crisis.[31] When checking eligibility on GetCoveredNJ, the site will tell individuals whether they may qualify for the NJ FamilyCare program for low-cost coverage.

The combination of the new SBE and NJ FamilyCare provides opportunities for more New Jerseyans to gain affordable health insurance coverage. As COVID-19 continues to ravage the country, lawmakers need to continue to support and expand these programs to guarantee the best health outcomes for all New Jerseyans.

How can state lawmakers further strengthen the state exchange?

New Jersey lawmakers still have opportunities to strengthen the state exchange by addressing challenges faced in other states implementing SBEs. Major challenges for SBEs in other states have resulted from: a lack of sufficient funding; ineffective communication about the SBE; technological difficulties; limitations on eligibility; and an unstable political environment surrounding the ACA. In learning from these lessons, New Jersey can better address issues of racial inequities and discouragement amongst uninsured residents most in need of affordable coverage.

Some of the key recommendations include:

Expand Eligibility

The SBE does not currently address the need for coverage options for undocumented residents living in New Jersey. Approximately 225,000 New Jerseyans live in households with at least one person filing taxes using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN).[32] These numbers are issued to those who are ineligible for a Social Security Number, including undocumented immigrants, as well as to those with certain other documented statuses, such as spouses and children of those on an employment visa. While not all ITIN filers or their family members are undocumented, it is estimated that a significant number are.[33] Additionally, not all undocumented individuals have ITINs, expanding the number of people affected by the narrow eligibility policies guiding ACA exchanges. Extending coverage options to undocumented individuals, and further ensuring that those living in households with undocumented individuals are confident in gaining coverage, is essential for increasing New Jersey’s coverage rate and protecting public health.[34]

Prioritize Programs that Address Language Barriers and Outreach

The GetCoveredNJ website is offered in both English and Spanish, with additional assistance available in other languages commonly spoken in New Jersey (such as Chinese, Portuguese, Italian, Tagalog, Korean, Gujarati, Polish, Hindi, and Arabic).[35] A key part of outreach and making sure that residents are getting enrolled will be to ensure that the resources available are meaningfully translated and easily accessible for those residents.[36] If the translations are technically accurate but use jargon or vocabulary that is not used conversationally in a language, the effectiveness of the materials can be weakened. Making sure to include feedback from native speakers will help to address these issues.

Make the Exchange More Easily Accessible for Those with Seasonal or Inconsistent Income

Another challenge of the exchanges lies in ensuring ease of eligibility determination and enrollment for individuals and families that may have inconsistent or seasonal income. People with low incomes often face the challenge of “churning,” or the involuntary movement between coverage systems. This can be especially problematic for people whose incomes qualify them for Medicaid, but with temporary boosts in income, such as those from seasonal or gig work, may find themselves with income that qualifies them for Marketplace coverage instead.[37] This movement between coverage options can lead to periods of interrupted coverage and worsening health outcomes.[38] Additionally, the enrollment forms can prove confusing for those whose income is not consistent or easily predicted for the year. Ensuring that enrollment forms are clear and provide detailed instructions for people with seasonal or inconsistent income on how to complete them is important for getting and keeping those individuals covered. Additionally, finding ways to move people more easily between exchanges and Medicaid when their eligibility changes will help to address this issue.

Anticipate and Plan for Technological Difficulties

When other states opened their SBEs, the experiences and smoothness of the rollout varied. Much of this depended on how much state authorities anticipated difficulties for consumers and sought to address them early and quickly. Extensive testing of and improvements to the website, as well as channels for customer feedback and clear communication when there is an issue needing to be addressed, were key for those states that were successful.

Additionally, ensuring that a clearly-marked “no wrong door” enrollment and eligibility system is in place will help to lessen the technological difficulties faced by people seeking to enroll in coverage.[39] A user-friendly and non-repetitive application structure without bias toward a particular program on the exchange website can ease enrollment into the appropriate coverage option, whether it is the Marketplace, NJ FamilyCare, Medicare, or another program. Without creating these easy-to-use application channels, consumers can become frustrated or confused and leave the enrollment process even when they are eligible for affordable coverage.[40]

Safeguard Against the Possibility of ACA Overturn

The future of New Jersey’s SBE is under threat by the ongoing efforts to have the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) overturn the ACA, as it would deem that everything included in the law, including the model for the exchanges, unconstitutional.[41] If the ACA is overturned, state lawmakers would have to pass a law that re-establishes the guidelines for the state-based exchange in order to continue offering plans in this manner. This could create instability in the insurance Marketplace and leave hundreds of thousands of New Jerseyans stranded without coverage. While New Jersey has already passed laws at the state level on many of the protective aspects of the ACA, such the guarantee for coverage for those with pre-existing conditions and a child’s ability to stay on a parent’s plan until age 26, a plan for the continuation of the exchange at the state level if the ACA is overturned is advisable.

End Notes

[1] National Academy of Social Insurance (2011). “Designing an Exchange: A Toolkit for State Policymakers.” January 2011. Online: https://www.nasi.org/sites/default/files/research/Designing%20an%20Exchange_A%20Toolkit%20for%20State%20Policymakers.pdf

[2] Sometimes, “Marketplace” is used in place of “health exchange,” with the resulting term being “State-Based Marketplace,” or SBM. In this report, I chose to use “State-Based Exchange” (SBE) because this keeps the terminology consistent with the language used by the New Jersey state government. Additionally: small businesses cannot buy plans directly through New Jersey’s GetCoveredNJ. Instead, small group employers can shop for plans through the Small Business Options Program (SHOP), which is required by the ACA to be set up alongside the exchange. More information can be found here: https://nj.gov/getcoverednj/findanswers/faqs/smallemployer.shtml. Additionally, discussion of SHOP markets and their relation to SBEs can be found at: Haase, Leif Wellington, David Chase, and Tim Gaudette (2017). “Talking SHOP: Revisiting the Small-Business Marketplaces in California and Colorado.” The Commonwealth Fund. 18 July 2017. Online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2017/jul/talking-shop-revisiting-small-business-Marketplaces-california

[3] A person’s financial assistance will differ depending on income, number of household members, and location of residency. Additionally, the amount a person pays per month will depend on the plan they choose. Plans are divided into “metals”: Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum. These differ in the way that they split the costs, with Bronze plans having the lowest monthly premiums but the highest costs at the point of service, and Platinum plans having the highest monthly premiums with the lowests costs at the point of service. For more information, see: HealthCare.Gov (2020). “How to pick a health insurance plan: The ‘metal’ categories: Bronze, Silver, Gold & Platinum.” Online: https://www.healthcare.gov/choose-a-plan/plans-categories/

[4] Anderson, Karen M. and Steve Olson (2015). “Chapter 2: The Potential of the ACA to Reduce Health Disparities.” Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity and the Elimination of Health Disparities; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Institute of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington DC: National Academies Press; Schwab, Rachel and Sabrina Corlette (2019). “ACA Marketplace Open Enrollment Numbers Reveal the Impact of State-Level Policy and Operational Choices on Performance.” The Commonwealth Fund. 16 April 2019. Online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/aca-Marketplace-open-enrollment-numbers-reveal-impact

[5] National Academy for State Health Policy (2019). “State-based Health Insurance Marketplace Performance.” September 2019. Online:https://www.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/SBM-slides-final_SeptMtgs-9_23_2019.pdf

[6] Kaiser Family Foundation (2020). “State Health Insurance Marketplace Types, 2021.” Online: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-health-insurance-Marketplace-types

[7] One policy that may be implemented under a potential Biden administration could be an expansion of the open enrollment period on the federal exchanges as well.

[8] GetCoveredNJ (2020). “What to Expect.” Online: https://nj.gov/getcoverednj/getstarted/expect/index.shtml

[9] GetCoveredNJ (2020). “About Us.” Online: https://nj.gov/getcoverednj/help/about/

[10] Texas Health Institute (2016). “Advancing Health Equity in the Health Insurance Marketplace: Results from Connecticut’s Marketplace Health Equity Assessment Tool (M-HEAT).” October 2016. Online: https://www.texashealthinstitute.org/uploads/1/3/5/3/13535548/connecticut_m-heat_final_report_-_october_2016.pdf

[11] For 2021, the Trump administration has dedicated only $10 million in total for all of the FFE states. Some states received no funding. Pollitz, Karen and Jennifer Tolbert (2020). “Data Note: Limited Navigator Funding for Federal Marketplace States.” Kaiser Family Foundation. 13 October 2020. Online: https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/data-note-further-reductions-in-navigator-funding-for-federal-Marketplace-states/

[12] Office of Governor Phil Murphy (2020). “Murphy Administration Announces $3.5 Million Investment in State Navigators to Assist Uninsured and Underserved New Jerseyans With ACA Health Insurance Enrollment.” 16 September 2020. Online: https://nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/approved/20200916a.shtml

[13] Office of Governor Phil Murphy (2019). “ICYMI: New Jersey Will Provide $2 Million in Navigator Grants & Outreach Funding to Assist New Jerseyans with ACA Enrollment.” 3 October 2019. Online: https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562019/20191003b.shtml; Pollitz, Karen, Jennifer Tolbert, and Maria Diaz (2018). “Data Note: Further Reductions in Navigator

Funding for Federal Marketplace States.” Kaiser Family Foundation. September 2018. Online: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Data-Note-Further-Reductions-in-Navigator-Funding-for-Federal-Marketplace-States; Stainton, Lilo H. (2017). “NJ Loses Federal Funding to Expand ACA Enrollment.” NJ Spotlight. 12 October 2017. Online: https://www.njspotlight.com/2017/10/17-10-11-nj-loses-federal-funding-to-expand-aca-enrollment/

[14] Office of Governor Phil Murphy (2020). “Governor Murphy Signs Legislation to Restore a Key Provision of the Affordable Care Act and Lower the Cost of Health Care in New Jersey.” 31 July 2020. Online: https://nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/approved/20200731a.shtml

[15] Holom-Trundy, Brittany (2020). “New Jersey Can Act Now to Make Health Care More Affordable: The Health Insurance Assessment Explained.” New Jersey Policy Perspective. 13 July 2020. Online: https://www.njpp.org/publications/explainer/new-jersey-can-act-now-to-make-health-care-more-affordable-the-health-insurance-assessment-explained/

[16] National Academy for State Health Policy (2019). “State-based Health Insurance Marketplace Performance.” September 2019. Online: https://www.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/SBM-slides-final_SeptMtgs-9_23_2019.pdf

[17] Lueck, Sarah (2019). “Reinsurance Basics: Considerations as States Look to Reduce Private Market Premiums.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 3 April 2019. Online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/reinsurance-basics-considerations-as-states-look-to-reduce-private-market-premiums

[18] Corlette, Sabrina, Kevin Lucia, Katie Keith, and Olivia Hoppe (2019). “States Seek Greater Control, Cost-Savings by Converting to State-Based Marketplaces.” Urban Institute. 10 October 2019. Online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/10/states-seek-greater-control-cost-savings-by-converting-to-state-based-Marketplaces.html.

[19] Kaiser Family Foundation (2020). State Health Insurance Marketplace Types, 2021. Online: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-health-insurance-Marketplace-types/

[20] Schwab, Rachel and JoAnn Volk (2019). “States Looking to Run Their Own Health Insurance Marketplace See Opportunity for Funding, Flexibility.” The Commonwealth Fund. 28 June 2019. Online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/states-looking-to-run-their-own-health-insurance-Marketplace-see-opportunity.

[21] Kaiser Family Foundation (2020). “State Health Insurance Marketplace Types, 2021.” Online: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-health-insurance-Marketplace-types

[22] NJPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. U.S. Census Bureau (2020). American Community Survey, 2019 1-Year Estimates. Online: http://www.data.census.gov.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Munira Z. Gunja, Gabriella N. Aboulafia, and Sara R. Collins (2019). “What Young Adults Should Know About Open Enrollment.” The Commonwealth Fund. 31 October 2019. Online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/what-young-adults-should-know-about-open-enrollment

[25] NJPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. U.S. Census Bureau (2020). American Community Survey, 2019 1-Year Estimates. Online: http://www.data.census.gov.

[26] NJPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. U.S. Census Bureau (2020). American Community Survey, 2019 1-Year Estimates. Online: http://www.data.census.gov. Official Federal Poverty Level (FPL) guidelines for 2020 can be found through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/aspe-files/107166/2020-percentage-poverty-tool.pdf

[27] NJPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. U.S. Census Bureau (2020). American Community Survey, 2019 1-Year Estimates. Online: http://www.data.census.gov. Official Federal Poverty Level (FPL) guidelines for 2020 can be found through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/aspe-files/107166/2020-percentage-poverty-tool.pdf

[28] Norris, Louise (2020). “How immigrants can obtain health coverage.” Healthinsurance.org. 18 May 2020. Online: https://www.healthinsurance.org/obamacare/how-immigrants-are-getting-health-coverage/

[29] In 2021, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) defines “affordable” coverage as coverage that requires an employee to contribute less than 9.83% of household income. See: Norris, Louise (2020). “Is the IRS changing how much I’ll have to pay for my health insurance next year?” Healthinsurance.org. 15 August 2020. Online: https://www.healthinsurance.org/faqs/is-the-irs-saying-ill-have-to-pay-more-for-my-health-insurance-next-year/

[30] Kaiser Family Foundation (2020). “FAQ: Can family members in families with mixed immigration status, where some family members are citizens or lawfully present and others are undocumented, enroll in Medicaid or CHIP or receive help buying coverage through the Marketplaces?” Online: https://www.kff.org/faqs/faqs-health-insurance-Marketplace-and-the-aca/can-family-members-in-families-with-mixed-immigration-status-where-some-family-members-are-citizens-or-lawfully-present-and-others-are-undocumented-enroll-in-medicaid-or-chip-or-receive-help-buying/

[31] Holom-Trundy, Brittany (2020). “COVID-19 Job Loss Leaves More Than 100,000 New Jerseyans Uninsured.” New Jersey Policy Perspective. 6 August 2020. Online: https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/covid-19-job-loss-leaves-more-than-100000-new-jerseyans-uninsured/

[32] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (2020). “Analysis: How the HEROES Act Would Reach ITIN Filers.” 14 May 2020. Online: https://itep.org/analysis-how-the-heroes-act-would-reach-itin-filers/; Kapahi, Vineeta (2020). “Building a More Immigrant Inclusive Tax Code: Expanding the EITC to ITIN Filers.” New Jersey Policy Perspective. 15 June 2020. Online: https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/building-a-more-immigrant-inclusive-tax-code-expanding-the-eitc-to-itin-filers/

[33] Kolker, Abigail (2020). “Noncitizens and Eligibility for the 2020 Recovery Rebates.” Congressional Research Service. 1 May 2020). Online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11376

[34] Other states have recognized this same dilemma for undocumented residents and begun taking steps to expand eligibility. For example, California sought to expand coverage through a waiver in 2016, but subsequently withdrew their application when the Trump Administration came into office due to their administration’s anti-immigrantion stance. It is anticipated that these types of efforts to expand eligibility will continue, and New Jersey will be able to learn from the experiences of other states in this process. For information on California’s effort, see Ibarra, Ana B. and Chad Terhune (2017). “California Withdraws Bid To Allow Undocumented To Buy Unsubsidized Plans.” Kaiser Health News. 20 January 2017. Online: https://khn.org/news/california-withdraws-bid-to-allow-undocumented-immigrants-to-buy-unsubsidized-obamacare-plans/

[35] New Jersey Department of Transportation (2012). “NJ Population by Language Spoken.” Online: https://www.state.nj.us/transportation/business/civilrights/pdf/map_language.pdf

[36] Texas Health Institute (2016). “Advancing Health Equity in the Health Insurance Marketplace: Results from Connecticut’s Marketplace Health Equity Assessment Tool (M-HEAT).” October 2016. Online: https://www.texashealthinstitute.org/uploads/1/3/5/3/13535548/connecticut_m-heat_final_report_-_october_2016.pdf

[37] Bergal, Jenni (2014). “Millions Of Lower-Income People Expected To Shift Between Exchanges And Medicaid.” Kaiser Health News. 6 January 2014. Online: https://khn.org/news/low-income-health-insurance-churn-medicaid-exchange/

[38] Hancock, Jay (2017). “Churning, Confusion And Disruption — The Dark Side Of Marketplace Coverage.” Kaiser Health News. 7 December 2017. Online: https://khn.org/news/churning-confusion-and-disruption-the-dark-side-of-Marketplace-coverage/

[39] Lueck, Sarah (2020). “Adopting a State-Based Health Insurance Marketplace Poses Risks and Challenges.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 6 February 2020. Online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/adopting-a-state-based-health-insurance-Marketplace-poses-risks-and-challenges

[40] Sprung, Andrew (2020). “Op-Ed: NJ’s new state-run health insurance exchange must learn from the mistakes of others.” NJ Spotlight. 23 October 2020. Online: https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/10/op-ed-njs-new-state-run-health-insurance-exchange-must-learn-from-the-mistakes-of-others/

[41] The case currently being considered that threatens this is Texas v. California. More information about this case can be found on the SCOTUSblog here: https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/texas-v-california/