Signed into law in March 2021, the American Rescue Plan (ARP) provided billions of dollars in flexible funding for states and local governments to begin reversing the harms done by the pandemic and promote an equitable economic recovery. Used correctly, these funds offer the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to advance racial equity by investing in Black and Hispanic/Latinx communities that were hardest hit by the pandemic.

In its official guidance to states, the U.S. Treasury explicitly encourages using flexible funding to “foster a strong, inclusive, and equitable recovery, especially with long-term benefits for health and economic outcomes” in mind.[i] Rather than a scattershot approach, New Jersey’s plans for these unprecedented federal dollars should focus on supporting low-paid workers, their families, and communities who need the most help. This analysis explores the extent to which allocations made so far have targeted these communities and suggests ways that New Jersey lawmakers can meaningfully advance equity with the remaining $3 billion in federal funds.

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (FRF) can be used to reimburse states and localities for pandemic-related costs and to support families and communities most harmed by the pandemic. New Jersey state government received $6.2 billion in flexible aid; counties and municipalities received an additional $3.6 billion.[ii]

The Biden administration strongly suggests that state and local governments use federal relief to bolster public health, promote economic security, fund services for disproportionately harmed communities, invest in infrastructure, and provide essential workers with hazard pay.[iii] On the flip side, funds cannot be used to pay off debt or shore up a rainy day fund or other financial reserves. Nor can they fund public-worker pension payments or offset revenue losses caused by new tax cuts. States must allocate all funding by the end of 2024 and have until the end of 2026 to spend it.

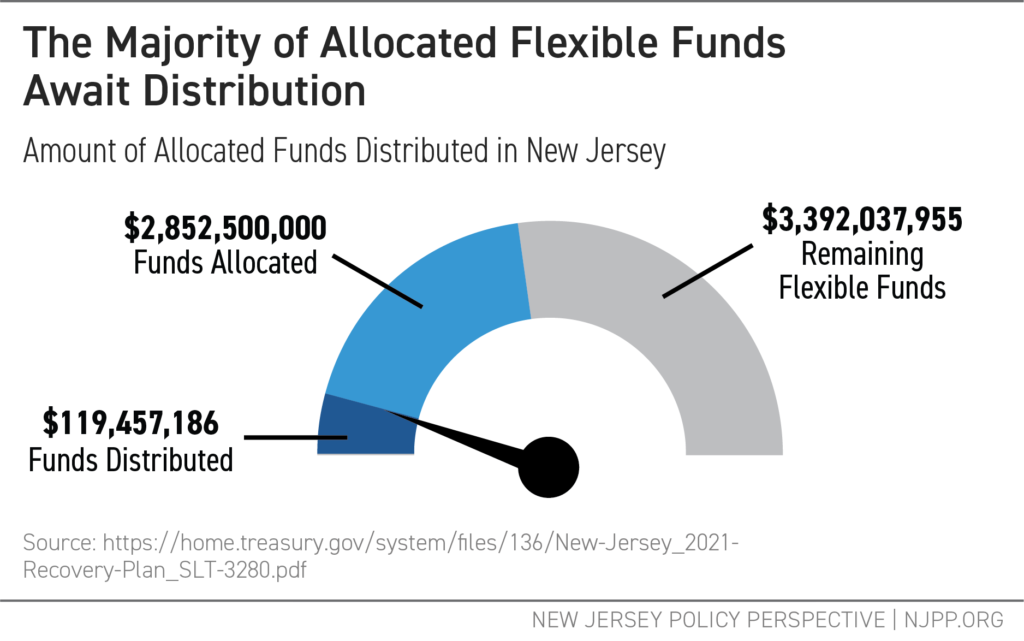

The good news is that roughly half of New Jerseys $6.2 billion in flexible funds have been allocated so far, helping renters, public hospitals, small businesses, and child care providers, among others in need.[iv] New Jersey’s allocation rate is in line with other states.[v]

The bad news is that less than 5 percent of the allocated FRF dollars have actually gotten into the hands of the designated recipients.[vi] Until new programs get off the ground or existing programs use up other federal funds first, the money remains with the state Treasury. A similar lag occurred last year with the Coronavirus Relief Funds established under the CARES Act.[vii]

Tracking How New Jersey Has Spent Federal Pandemic Relief

The pandemic and resulting economic fallout has disproportionately harmed Black and Latinx/Hispanic communities — a harsh reflection of longstanding inequities in education, employment, housing, and health care driven by our nation’s legacy of slavery and systemic racism. The most effective way to advance equity is to target aid to these communities and begin reversing racial and ethnic disparities exacerbated by past policy choices.

But do the first rounds of emergency funding achieve this? Looking at these FRF allocations by specific sectors and affected communities identified by the Biden administration may offer some answers.

Services for Disproportionately Harmed Communities

Since receiving FRF dollars in May 2021, New Jersey has allocated $700 million to services for families and communities disproportionately harmed by the pandemic due to pre-existing health and economic disparities. . Special education received the bulk of funds in this category, with smaller investments steered to food assistance, lead hazard removal, and direct assistance for workers excluded from other relief programs. So much more could be done to provide assistance to these households and communities. Recommended projects that would directly respond to disproportionate impacts of the pandemic include re-employment training, vacant or abandoned property remediation, and services to address educational disparities and students’ social, emotional, and mental health needs.

Economic Harm from the Pandemic

State lawmakers have allocated $1.3 billion to address economic harm from the pandemic. Allocations made under this category may be used to assist struggling households, small businesses, and nonprofits, or to aid especially hard-hit industries such as tourism, travel, and hospitality.

The largest allocation so far, rental and utilities assistance, hits the mark as appropriately targeted to helping those who need the most help, as does support for affected businesses. But it’s questionable if aid for such projects as dredging the Woodbridge municipal marina or building a new visitor center at Great Falls — has any beneficial effect on low-income, Black, Hispanic/Latinx, or other disproportionately-affected communities.

A lack of intention or inadequate analysis of health or economic equity results in unclear benefits for certain programs. For example, “Return and Earn,” a subsidized job program covering the costs of wages paired with cash incentives, aims to help small businesses and workers get back on track, but it’s unclear whether these businesses and workers are focused on hardest-hit communities. Using FRF for services unrelated to pandemic recovery ignores the needs of households facing immediate hardships and neglects the opportunity these dollars present to address structural inequalities.

Premium Pay for Essential Workers

Premium pay, also known as hazard pay, is designed to compensate essential workers who faced — and continue to face — heightened risks and additional burdens during the pandemic. Many of these workers earn lower wages on average and are disproportionately Black and Hispanic/Latinx.[viii]

New Jersey has yet to recognize the enormous risk workers in health care, food service, education, and logistics were exposed to during the shutdown.[ix] These essential workers deserve fair compensation, yet they continue to be overlooked in federal relief and recovery legislation. Directing premium pay to those with limited income and those who often went without basic health and safety protections would make an immediate difference to these workers. One potential formula calls for up to 160 hours of hazard pay at $13 per hour for health care workers and up to 80 hours of hazard pay at $13 per hour for other essential workers.

How New Jersey Can Advance Equity with Remaining Federal Funds

New Jersey’s distribution of the remaining $3 billion in recovery funds must pivot to a strategy that advances racial, ethnic, and gender equity. That means prioritizing more financial support for working people paid too little to make ends meet, Black and Latinx/Hispanic residents, and immigrants. These are the households that suffered — and continue to suffer — harshly disproportionate economic and health consequences of the pandemic. It also means strengthening infrastructure in communities that have long suffered from underinvestment. Failing to use federal money to serve these purposes would be a lost opportunity to create a more equitable New Jersey.

End Notes

[i] SFRF Interim Final Rule (IFR) at 31 C.F.R. §35.6 (b) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-05-17/pdf/2021-10283.pdf

[ii] Cory Booker Press Release, Menendez, Booker Release More Details on How American Rescue Plan will Help NJ, March 2021. https://www.booker.senate.gov/news/press/menendez-booker-release-more-details-on-how-american-rescue-plan-will-help-nj

[iii] SFRF Interim Final Rule (IFR) at 31 C.F.R. §35.6 (b) https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-05-17/pdf/2021-10283.pdf

[iv] New Jersey Governor’s Disaster Recovery Office, Financial Summary by Federal Act, December 2021. https://gdro.nj.gov/tp/en/financial-analysis/financial-summary

; State of New Jersey, 2021 Recovery Plan Performance Report, August 2021. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/New-Jersey_2021-Recovery-Plan_SLT-3280.pdf

[v] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, How States Can Best Use Federal Fiscal Recovery Funds: Lessons From State Choices So Far, November 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/how-states-can-best-use-federal-fiscal-recovery-funds-lessons-from

[vi] NJPP correspondence with Governor Murphy Senior Staff, January 27, 2022. The Bergen Record, NJ got $6 billion in COVID-19 federal relief. This is how it’s being spent, so far, Sept 2021. https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/new-jersey/2021/09/13/nj-covid-federal-spending/5782777001/

[vii] Pandemic Response Accountability Committee of the Council of the Inspector Generals on Integrity and Efficiency. https://www.pandemicoversight.gov/track-the-money/funding-charts-graphs/coronavirus-relief-fundOversight

[viii] American Journal of Public Health, Reopening the United States: Black and Hispanic Workers Are Essential and Expendable Again, October 2020. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305879

[ix] State of New Jersey, 2021 Recovery Plan Performance Report, August 2021. https://nj.gov/covid19oversight/transparency/reports/docs/20210831FINALNJRecoveryPlan.pdf and New Jersey Department of Treasury, Office of Management and Budget’s Request for State Fiscal Recovery Fund Program Approval by Joint Budget Oversight Committee, November 2021. https://www.senatenj.com/uploads/23NOV2021-ARP-SFRF-Program-Approval-Request-JBOC-Memo-002.pdf