To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

New Jersey’s corporate tax code is littered with loopholes, special breaks and preferential treatment for large and well-connected corporations. This broken system caused the state to lose billions of dollars over the past decade – billions that could be better used to help create a prosperous state with a strong economy and thriving communities in the coming decades.

Four states and the District of Columbia levy higher corporate business tax rates than New Jersey’s 9 percent rate.[1] And with the help of tax loopholes, rebates and subsidies, many larger corporations operating in New Jersey are paying just a fraction of the statutory rate, and some none at all.

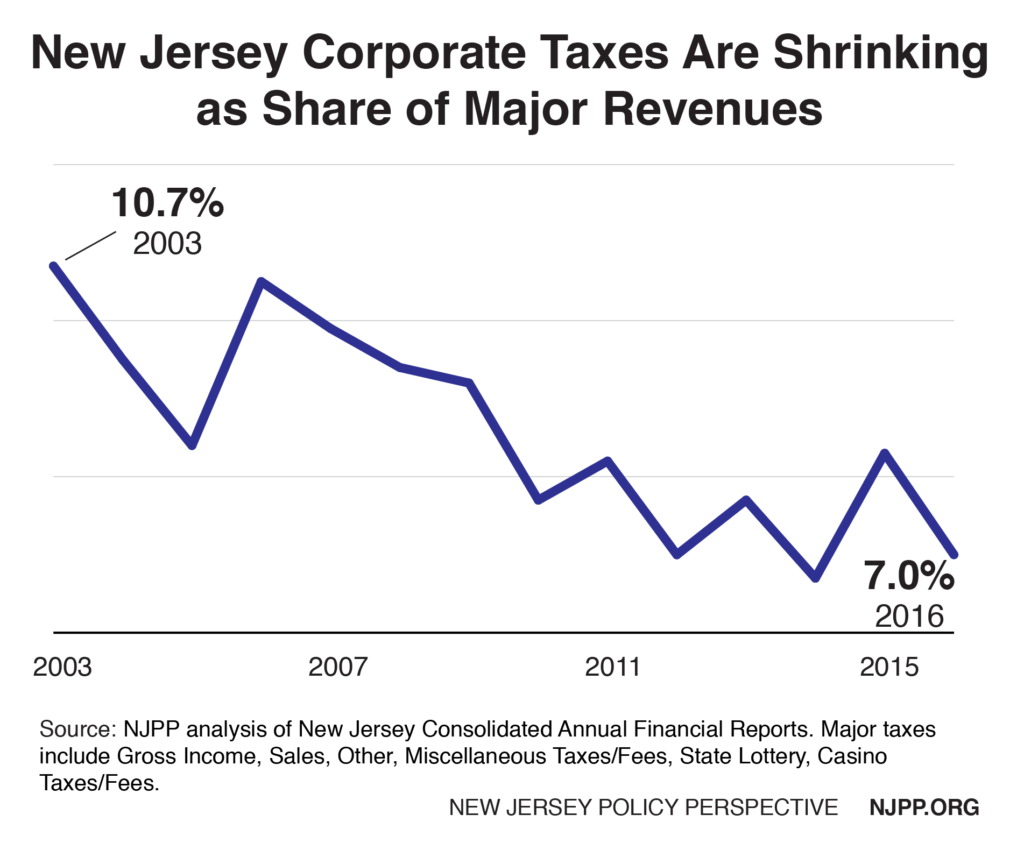

Partly as a result of this fact, corporate taxes have been a shrinking share of state revenues even as, on the whole, businesses have fared quite well. This has led New Jersey to rely more on income and sales taxes while putting a strain on the state’s ability to invest in services that all businesses rely upon. Without the necessary reforms, revenue from New Jersey’s corporate business tax will continue to stagnate, forcing the state to either raise other state taxes or diminish vital public services to make ends meet.

For example, there are at least 25 Fortune 500 companies doing business in the Garden State that effectively pay an average 3.5 percent in business taxes in all states where they operate.[2] Eleven of those 25 profitable corporations paid no state income tax at all in at least one year between 2008 and 2015 costing states over $12 billion in total lost revenue in the past decade.

Policymakers ought to level the playing field and allow small businesses a better chance of competing with larger companies while raising the revenue necessary to help the entire economy thrive – not just the shareholder set. And federal proposals to cut corporate taxes may mean that New Jersey needs to do even more to ensure all businesses have a fair shot and larger corporations aren’t gaming the system.

New Jersey lawmakers should:

- Close corporate tax loopholes by expanding combined reporting

- Rein in corporate subsidy programs

- Repeal or reform some recent business tax breaks

Taking these actions could raise over $450 million a year in new revenue, while relieving long-term budget pressures that will plague New Jersey for years to come if not addressed. Without these meaningful reforms, New Jersey will be crippled in its ability to provide public services and make investments that actually help the economy grow.

Close Major Corporate Loopholes

New Jersey’s broken tax code currently allows large multistate corporations to – on paper – shift profits they make here to other states that have lower tax rates, or no corporate taxation at all. Corporations often do this by creating “subsidiaries” that exist only for tax purposes. States are combating this by adopting what is called combined reporting, and New Jersey should join them. Doing so would help level the playing field for the state’s small and local businesses and raise up to $290 million a year in new revenue to invest in resources entrepreneurs and businesses across the state need to thrive.[3]

Combined reporting is a common-sense tax policy that treats the parent company and subsidiaries of multistate corporations as one entity for state corporate income tax purposes. Their nationwide profits are added together and the state then taxes its appropriate share of the combined income. Right now the state’s casinos are the only entities required to follow combined reporting rules. Expanding combined reporting to all multistate corporations would put New Jersey in line with 25 other states that require it.

These states recognize that failing to include combined reporting in their corporate income tax structures gives profitable multistate corporations almost free rein to artificially shift income out of the state and reduce their taxes. Combined reporting stops these corporations from taking advantage of existing tax loopholes and new ones that corporate accountants may come up with in the future.

These states recognize that failing to include combined reporting in their corporate income tax structures gives profitable multistate corporations almost free rein to artificially shift income out of the state and reduce their taxes. Combined reporting stops these corporations from taking advantage of existing tax loopholes and new ones that corporate accountants may come up with in the future.

When New Jersey’s legislature last addressed business tax reform in 2002, combined reporting was mostly left off the table. A commission appointed to review the new law essentially tabled the possibility of expanding combined reporting beyond the casino industry. At that time, only 16 states had fully adopted combined reporting. Since then, nine more states plus Washington D.C. have passed legislation to require this pragmatic corporate tax policy. And policymakers in several other states – including Louisiana, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Mexico and Alabama – are currently considering mandatory combined reporting legislation.

In fact, combined reporting is so commonplace that nearly all of New Jersey’s largest employers already use it when filing state taxes elsewhere. Of the state’s 98 largest employers, 94 percent already maintain facilities in at least one combined reporting state. And the vast majority of these corporations maintain facilities in multiple combined reporting states. More than 75 percent have facilities in five or more combined reporting states and about half have facilities in 10 or more such states.[4] That speaks volumes about the neutral impact this tax policy has on economic development. For these corporations, combined reporting is nothing out of the ordinary and is accepted as just another cost of doing business.

Put the Brakes on Corporate Tax Breaks

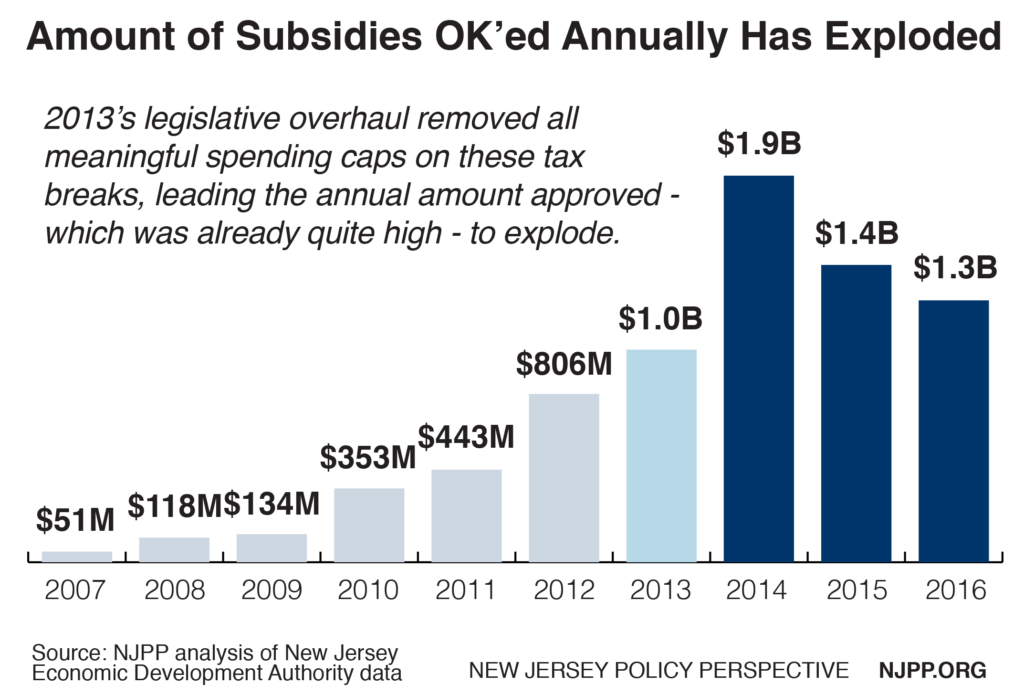

Because of legislative changes made in 2013, New Jersey’s surge in corporate tax subsidies has risen to unprecedented levels, further cramping New Jersey’s ability to invest in schools, transportation and other areas known to be the real drivers of job creation.

The “Economic Opportunity Act of 2013” dramatically expanded corporate tax break offerings, making them more generous to corporations and removing key financial safeguards, including most ceilings on how much the state can spend on subsidies. The increasing reliance on big-dollar tax breaks has done little to significantly improve the state’s economy, and will in fact cause a long-term drag on growth as future tax credits are paid out over the next decade. After all, every dollar that the state loses to future tax subsidies is a dollar it can’t invest in the true building blocks of a strong state economy like affordable public colleges and universities, safe and reliable infrastructure and more.

As of November 2017, New Jersey has approved $5.7 billion under the 2013 law, and $8.3 billion total since January 2010. And it’s not just the overall amount of subsidies that has exploded. These tax breaks have become far more expensive to taxpayers – with the state giving up more and more tax dollars for each job a subsidy recipient creates or retains. The cost per job is now about $80,000 – twice the amount it cost earlier this decade and more than five times higher than the cost in the 2000s.[5]

And the long-term cost to all of us is enormous, with the official estimate for 2017-2021 alone at $3.3 billion in lost revenue.[6] (It’s worth noting that this is merely the tip of the iceberg in terms of the true long-term fiscal impact. NJPP estimates that once the annual revenue loss tops $1 billion a year – likely to happen in 2022 – New Jersey will lose at least $1 billion a year for at least the next 10 years.)

Ten key reforms could help rebalance the scales and ensure a more responsible approach to economic development in the Garden State:[7]

- Restore spending caps

- Mandate better reporting on outcomes and improve evaluation

- Fix the net benefits test to prevent taxpayer losses after companies exit

- Eliminate, or develop more stringent standards for, subsidies for existing jobs

- Put subsidies in the state budget

- Restrict corporations’ ability to redeem more in credits than they owe in taxes

- Ensure fair wages

- Prevent extra rewards for known federal tax dodgers

- Include automatic sunset provisions

- Cooperate with, rather than compete against, New Jersey’s neighbors

These reforms would help put New Jersey back on track before more damage is done to the state’s economy and before the bills we’re passing on to future taxpayers become even larger. Reining in the use of tax breaks for large corporations would allow policymakers to focus more on economic-development strategies that offer much better returns, like targeted job training or entrepreneurial assistance, for example.

Repeal or Reform Recent Business Tax Breaks

Rolling back some recent costly tax breaks for businesses and replacing them with viable alternatives could restore equity to the state’s tax code while raising more than $150 million a year that could be used to invest in assets and opportunities that drive economic growth for all the state’s businesses.

Reverse Tax Cut for Large S Corporations and Update Tax on LLCs

When new businesses incorporate in New Jersey, they have a choice between filing taxes as a C-corporation, a S-corporation or a limited liability company (LLC). C-corporations are taxed as a separate entity while S-corporations are taxed the same as a sole proprietor or partnership: the profits and losses are “passed-through” and reported on the owner’s personal tax returns.[8]

Although S-corporations’ profits are taxed on their owner’s personal income tax returns, the businesses themselves are subject to nominal fixed fees that are calculated based on gross receipts. This “minimum tax” ensures that these entities make a modest financial contribution toward state services, like the education system that furnish them with trained workers and a dependable transportation system for moving goods and services. Though some states do impose a separate tax or fee on LLCs for the privilege of doing business in the state, New Jersey does not.

Although S-corporations’ profits are taxed on their owner’s personal income tax returns, the businesses themselves are subject to nominal fixed fees that are calculated based on gross receipts. This “minimum tax” ensures that these entities make a modest financial contribution toward state services, like the education system that furnish them with trained workers and a dependable transportation system for moving goods and services. Though some states do impose a separate tax or fee on LLCs for the privilege of doing business in the state, New Jersey does not.

Policymakers in 2011 cut the minimum tax by 25 percent for all but the very largest S-corporations. Reversing course for S-corporations with more than $250,000 in gross receipts would recoup some of the lost $41 million in revenue and restore a meaningful tax on larger businesses that benefit from state services just as businesses that are subject to state corporate income taxes do.[9] To help pay for the reduced minimum tax on smaller S-corporations, lawmakers should consider imposing the same fee structure on LLCs to encourage level treatment of both pass-through entities.

Revise How New Jersey Taxes Multistate Businesses

Until 2012, New Jersey relied on three factors – property, sales and payroll – to determine the share of a multistate corporation’s profits that the state could tax. This “apportionment formula” was scrapped in 2011, and now New Jersey only takes into account one factor: sales. Known as the “single sales factor,” this formula has given many large multistate corporations a significant tax break that now costs New Jersey over $100 million every year.

The single sales factor formula can create perverse incentives that can deter economic growth in the state. If an out-of-state company that only ships products into the state (and thus pays no income tax to New Jersey) decides to put down roots here, even a small investment in employees or property will immediately mean much of its income is apportioned to the state because the sales factor counts so heavily. In fact, the most recent research finds that single sales factor does not achieve its asserted goal of boosting state economic development.[10]

New Jersey can address this problem and regain the revenue lost due to the single sales factor by adopting a measure called a “throwback rule.” The majority of states with corporate taxation have adopted this policy, which recoups taxable income by including so-called “nowhere sales” in the sales factor.[11]

“Nowhere sales” are not assigned to or taxed by any state because they are made by purchasers in states where a company has no physical presence. The throwback rule says that the profits from sales that are not taxable are “thrown back” and taxed in the state where the products are made. This rule then increases the relative weight of in-state sales in the sales factor, thus increasing the income apportioned to the taxing state. The lack of a throwback rule is currently costing New Jersey about $127 million in annual revenue, according to the state.[12]

Adopting a throwback rule in New Jersey would remove accounting features that reduce large corporations’ state tax bills at the expense of small businesses and the state’s ability to finance vitally important long-term public investments that all businesses depend on (like police and fire protection and mass transit). A bill to enact a throwback rule was introduced by Assemblyman Troy Singleton this year but has not moved in the legislature.[13]

Endnotes

[1] The Tax Foundation, State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2016, February 2016.

[2] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), 3 Percent and Dropping: State Corporate Tax Avoidance in the Fortune 500, 2008-2015, April 2017.

[3] New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Legislative Fiscal Estimate, Senate Bill No. 982, March 2016.

[4] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Nearly All of New Jersey’s Largest Employers Already Subject to ‘Combined Reporting’ in Other States, January 2016.

[5] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Economic Development Authority’s Public Information – Incentives Activity Reports, up-to-date through the EDA’s November 2017 meeting.

[6] New Jersey Economic Development Authority, Response to Office of Legislative Services Questions in Fiscal Year 2018 Budget Hearings, May 2017.

[7] For more detail, see New Jersey Policy Perspective, It’s Time for New Jersey to Rebalance the Economic-Development Scales, May 2017.

[8] Only those LLCs that elect to be treated as a corporation for tax purposes must pay the state’s corporation business tax.

[9] New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Fiscal Note Senate, No. 2981, July 2011.

[10] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Case for ‘Single Sales Factor’ Tax Cut Now Much Weaker, April 2015.

[11] New Jersey once had what is known as a “throwout rule,” whereby receipts from sales destined to a state where the taxpayer is not subject to an income tax are thrown out of both the numerator and denominator of the sales factor. The rule was subject to multiple constitutional challenges but upheld by the courts. Nonetheless, it was repealed for tax periods starting in fiscal year 2010. Repeal of the throwout rule cost the state $89 million annually [New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Taxation, Fiscal Note Senate, No. 3, November 2008. ftp://www.njleg.state.nj.us/20082009/S0500/3_F1.HTM]. Enacting a throwback rule would likely generate more revenue than that, because the throwout rule effectively assigns “nowhere” sales in the same proportion as a corporation’s existing in-state and out-of-state sales, while the throwback rule would assign all the “nowhere” sales to New Jersey.

[12] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Taxation, Tax Expenditure Report, Fiscal Year 2018.

[13] State of New Jersey Legislature, Assembly No. 4668, March 2017.