To download a PDF of this report, click here.

It’s time to set the record straight about who is moving in and out of New Jersey, why they do and what it means for the state’s wellbeing.

For too long the so-called conventional wisdom – fueled by fear mongering and unsubstantiated claims – has said that raising revenue in New Jersey by calling on the wealthiest to pay their share of taxes for the common good drives people, and their money, away.

First and foremost, there is no significant correlation between state taxes and interstate moves.

Job opportunities and family considerations are most commonly cited as reasons for moving from one state to another. If cost of living is a factor, it is more likely that the quest for lower-priced housing and property taxes drive the decision to move, rather than other state taxes.[1]

Second, proponents of cutting taxes for the wealthy use a misleading reading of Internal Revenue Service data when they contend that if a person moves from one state to another that automatically means the state they leave loses income as a result.[2]

The income level of someone who leaves is not an accurate measure of “income migration,” because in most cases a similar income will be earned by whoever fills that person’s job.

What’s more, even if one accurately uses IRS figures on the number of households moving, the patterns and data – if presented in context – tell a very different story than that peddled by business lobbying groups and others who would deprive New Jersey of resources needed to help communities thrive.[3]

• New Jersey’s population continues to grow, even though more people move out of New Jersey than move in from other states in any given year.

• The top 10 locations favored by former New Jerseyans include four states with taxes comparable to New Jersey: New York, California, Maryland and Massachusetts.

• A substantial majority of households moving out of New Jersey to neighboring states are replaced by households from those states moving into New Jersey.

• Florida is the third most popular destination for people leaving New Jersey, and almost half of those making such a move are 55 and over. The same holds true for retirees from many other northern states, some of which have no income taxes or low income taxes.

None of this would be true if New Jersey were “the incredible shrinking state” some would have us believe – a state being hollowed out because of tax rates.

In fact, New Jersey is home to excellent public schools and colleges; safe, walkable, vibrant communities; high-quality health care; the ocean and the beach; and plentiful mass transit options into New York and Philadelphia. These valuable assets and others are what make New Jersey an attractive place to live, work and raise a family for almost 9 million people.

Of course, as is the case with every state, some choose to leave the Garden State. For many, job opportunities elsewhere prompt the move. For others, it’s time to hang up the snow shovel once and for all and retire to a warmer climate.

And, yes, some may leave New Jersey to escape the level of taxes – particularly its highest-in-the-nation local property taxes. But the claim that New Jersey’s taxes, particularly its personal income or estate taxes, are responsible for harming the state’s economy by driving people away en masse, taking billions of state income with them – is dangerously misleading. For policy to be made on the basis of this misinformation is the real threat to New Jersey’s economic future.

Few People Move Across State Lines, and Even Fewer Do So Because of Taxes

Before examining the details of state-to-state movement patterns, it’s important to note that interstate migration is not as common as one would think. More than two-thirds of Americans reside in the state in which they were born. In fact, only 2 percent of U.S. residents make an out of state move per year, a slim rate that has been falling since 1990.[4]

Of the relatively few Americans who do relocate from one state to another, a very small subset cites taxes as the reason for their moves. Since 1998, the U.S. Census has asked people who move the main reason for relocating. The two most common reasons consistently cited are “new job or job transfer” and “family reasons,” such as a change in marital status. Other common answers include housing, closer commute, retirement and college. In the most recent survey, just 13 percent answered either “other reason” or “other housing reason.” Since the survey does not explicitly offer “lower taxes” as an option, this is likely how people for whom taxes is the major reason for a move may have chosen to answer.[5]

Several rigorous statistical studies of interstate moving patterns confirm that there is no meaningful correlation between state taxes and interstate moves.[6] For example, a new long-term study of top income-earners found that the vast majority of millionaires don’t move to avoid state taxes.[7] Another study specifically looked at the impact of New Jersey’s 2004 enactment of a higher tax rate on incomes of more than $500,000 and concluded that “the effect of the new tax bracket is negligible overall. Even among the top 0.1 percent of income earners, the new tax did not appreciably increase out-migration.”[8]

More importantly, the amount of new revenue gained from the tax change dwarfed the tax payments that would have been made by those few who left. The estimated revenue lost was less than 2 percent of the overall revenue gained. In other words, New Jersey did not lose money by increasing income tax rates on the wealthiest households.

The argument that the elderly, in particular, flee taxes by moving to lower-tax or no-tax states is also not supported by the empirical evidence. The patterns of state-to-state movement among the elderly have remained relatively consistent over time, even as state tax policies toward the elderly changed significantly across states.[9] If older people who leave New Jersey are heading to popular retiree destinations regardless of tax policy, there is no reason to offer them tax breaks in the hopes that they will stay.

Many New Jerseyans Move to High-Cost, High-Tax States

The trend of people moving out of New Jersey is by no means a recent phenomenon. Nor is losing a few thousand households every year unique to New Jersey. In fact, this is part of a decades-long demographic population shift from the Northeast and Midwest to the West and South, as working-age people seek job opportunities and retirees seek warmer climates.[10]

While New Jersey is a state where more people leave for other states than move in from other states, its taxes can’t be the primary reason, judging what which states they most commonly chose. Of the top 10 destination states for departing New Jerseyans between 2003 and 2014, many are, like New Jersey, relatively high-cost and high-tax states. For example, the number one destination state is New York — not exactly a low-tax state.

What’s more, New Jersey actually enjoyed a net gain of more than 84,000 former New Yorkers during that same time. There is clearly more to the story if people are choosing to move into high-tax states like New York or New Jersey rather than into lower-tax or no-tax states.

Also, more than 190,000 households left New Jersey for Pennsylvania between 2003 and 2014. And about 8 in 10 of them were replaced by Pennsylvania households moving to New Jersey. This begs the question: if taxes are such a major factor in making relocation decisions, why has New Jersey seen hundreds of thousands of households move in from both higher-tax New York and lower-tax Pennsylvania?

Naturally, Florida is high on the list of states to which New Jersey residents move, and, again, it is misleading to assume that its tax status is the driving force behind this trend. Florida has always been a popular destination for New Jersey retirees. But this is also true of retirees from several other cold states across New England and the northern half of the Midwest – states like New Hampshire, which has no broad-based income tax or sales tax and other states with very low single-rate income taxes (Pennsylvania, Indiana and Illinois). Florida’s warm weather and lower housing costs – not taxes alone – make it a popular choice for retirees and it is likely New Jersey retirees feel the same.

Another point to consider: Just over a decade ago, Florida and New Jersey imposed the exact same estate tax. At that time, the average net annual movement from New Jersey to Florida was 8,000 households. If the estate tax was chasing retirees from the Garden State to the Sunshine State, wouldn’t that number increase when Florida began phasing out its estate tax in 2002? In fact, the opposite happened. For the past eight years New Jersey-to-Florida movement has shrunk to a net average of 6,000 households per year.

The bottom line with data about people moving to and from New Jersey is that it doesn’t tell you much. And that’s just the point – there isn’t much to tell. The story promoted by those trying to convince policymakers that taxes drive people from New Jersey turns out to be just that – a story.

New Jersey’s Population, Number of Wealthy Residents and Income Are All Growing – Not Shrinking

Proponents of cutting taxes for the wealthy have framed the so-called “exodus” of New Jersey residents and income as a serious crisis that policymakers ignore at the state’s economic peril. They do so, in part, by ignoring the fact that New Jersey’s population and income are actually growing, not shrinking – leaving policymakers and the public to ponder solutions to problems that don’t actually exist.

The claim of business lobbying groups that New Jersey “lost more than 2 million residents” between 2005 and 2014[11] is simply untrue.

In fact, the 2,090,786 people who left the state over that time were replaced by 1,408,718 who moved here from other states and 596,279 who did so from abroad. So if you only look at people who moved, New Jersey – the nation’s most densely populated state – “lost” 85,789 people over the decade. That comes to less than 9,000 a year, less than a tenth of a percent in a state with nearly 9 million residents.

And, that count doesn’t include New Jerseyans who were born here and stayed here; if you also factor in growing families, the state’s population has consistently grown over the same decade, to 8.9 million in 2014 from 8.7 million in 2005.

The Garden State isn’t just growing in population. The state continues to gain millionaires and has a higher share of them than all but three states, according to one wealth management firm’s estimates of net worth and investable assets.[12] New Jersey has 29,371 more households with assets worth more than $1 million than it did in 2006. These families have risen to 7.2 percent of the state’s households in 2015 from 6.5 percent in 2006.

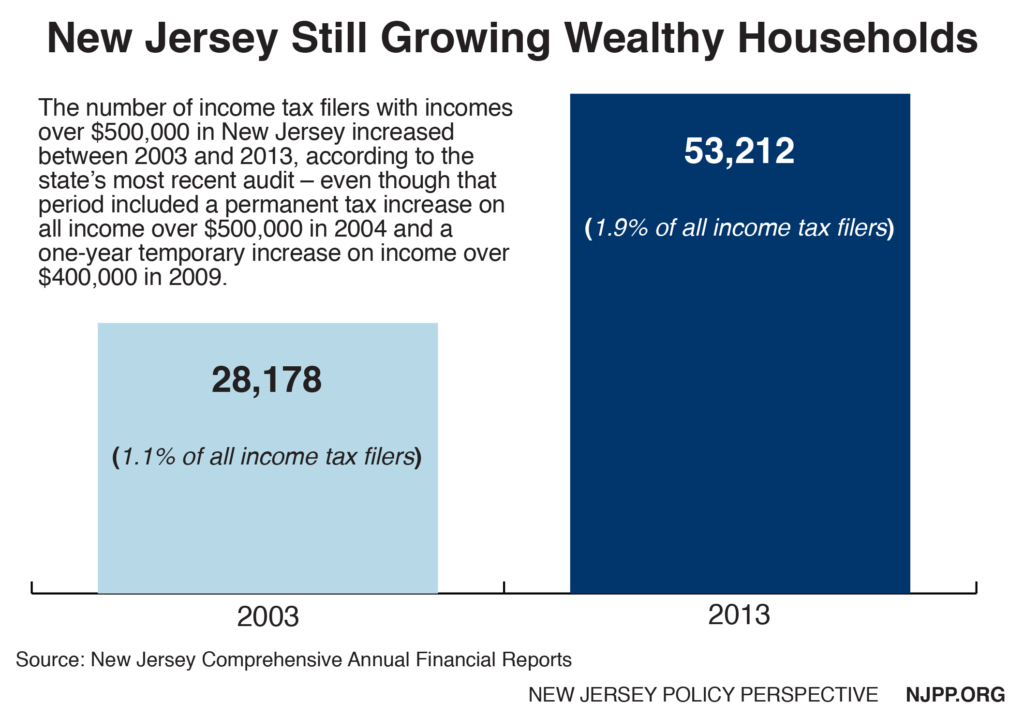

Confirmation of the growing number of wealthy households can also be found among New Jersey’s personal income tax filings, which are based solely on incomes, not assets.

Between 2003 and 2013, the number of New Jersey households with annual incomes over $500,000 increased by 89 percent, jumping to 53,212 from 28,178.[13] The share of wealthy households also rose to 1.9 percent of all income tax filers in 2013 from 1.1 percent in 2003.

It’s worth noting that this growth occurred during a time that state income tax rates were raised not once but twice on these wealthy households, and the growth was this healthy despite the temporary lull during the Great Recession.

Lastly, proponents of eliminating New Jersey’s taxes on inherited wealth suggest that many of these same well-off people who grow their wealth here leave once the end of their lives draws near, in order to save their heirs from an estate or inheritance tax bill.

While some older New Jerseyans may indeed leave the state to avoid these taxes, the supposed deleterious effect these moves have on the state’s economy and finances is wildly overstated – because revenue from these taxes is growing, not shrinking. Collections from these taxes have grown by 44 percent in the past 13 years,[14] and the state budget Gov. Christie proposed four months ago for the fiscal year that starts July 1 anticipates even more revenue from these taxes – an all-time high of $848 million.[15] The Office of Legislative Services 2017 estimate is now even higher, at $880 million.[16]

‘Income Migration’ Claims Are Inaccurate

The same group’s contention that New Jersey’s tax rates have created economic damage due to the so-called loss of $18 billion in New Jersey income between 2004 and 2013 is also wrong.

Some context is instructive.

Though 18 billion of anything sounds significant, the shock value diminishes once the income of the state as a whole is taken into account. During these same 10 years, the amount of income reported annually in the state grew by $103 billion, adding up to an impressive $2.5 trillion for the period as a whole. The supposed “loss” of $18 billion is a mere 0.7 percent of the total household income generated in New Jersey from 2004 through 2013.

So it’s barely a sliver when compared to the state’s entire economic pie. But the real number is even less than that because the $18 billion figure ignores what really happens to personal income when someone moves out of the state.

The vast majority of people actually don’t take their income with them to a new state – because they can’t. When people make an interstate move, they usually leave their job to take another, and the income they made in their previous job typically goes to the person who replaces them. That state income essentially stays put, which explains why New Jersey’s overall income reported each year grew significantly at the same time we “lost” that $18 billion.[17]

The same holds true for business owners if they leave the state. The money their business made goes to the new owner of the business if the old owner sold it, or other in-state businesses that pick up the customers of the one that left. If a doctor or a plumber or the owner of a restaurant leaves New Jersey, the patents and clients and customers don’t leave too.

For those moving out of state upon retirement, it is equally misleading to claim that New Jersey’s economy loses income equal to the person’s pre-retirement salary, because their income also would have declined if they had retired in New Jersey.

And in today’s mobile, technological age, some people may leave the state but continue to work or own a business in New Jersey. If so, they continue to contribute to the economy and pay taxes, though perhaps not as much as before their move. To categorize all of their income as “lost” to the economy of the state from which they moved is an exaggeration.

Instead of focusing on misleading claims about tax-motivated movement from New Jersey, policymakers should focus on improving policies that grow the incomes of current and future residents and the state economy at large. Deep cuts to – or outright repeals of – taxes on inherited wealth only leave the state with fewer resources to support colleges and universities, parks, roads, public safety and other foundations of the state’s prosperity. These are the things that make New Jersey a place where businesses want to invest and where people want to live and work.

Cutting taxes out of fear that wealthy people will leave New Jersey – and that they will take piles of money with them – is like a well-aimed shot in the foot. With no credible evidence that taxes dictate where people live – and lots of evidence that they don’t – policymakers should not forfeit a significant amount of revenue that the Garden State cannot afford to lose to forestall the loss of income tax revenue from a small group of people.

Endnotes

[1] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’ Interstate Moves, May 2014.

[2] Tax Policy Issues, Why People Use IRS Migration Data, March 2016.

[3] For an example of the misuse of this data, see NJBIA’s Outmigration by the Numbers: How Do We Stop the Exodus?

[4] Ibid 1

[5] Ibid 1

[6] Ibid 1

[7] American Sociological Review, Millionaire Migration and Taxation of the Elite: Evidence from Administrative Data, June 2016.

[8] National Tax Journal, Millionaire Migration and State Taxation of Top Incomes: Evidence from a Natural Experiment, June 2011.

[9] National Tax Journal, No Country for Old Men (Or Women): Do State Tax Policies Drive Away the Elderly?, June 2012.

[10] Brookings Institution, Sun Belt Migration Reviving, New Census Data Show, January 2016.

[11] New Jersey Business & Industry Association, Outmigration by the Numbers: How Do We Stop the Exodus?, February 2016.

[12] Phoenix Marketing International, 2015 Market Sizing Update & Millionaires By State Ranking, January 2016 and Ranking of U.S. States By Millionaires Per Capita 2006-2013, January 2014.

[13] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, available at http://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/archives.shtml

[14] Ibid 13

[15] State of New Jersey, The Governor’s FY2017 Budget Summary, February 2016.

[16] New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Remarks of Frank Haines, Legislative Budget and Finance Officer to the Senate Budget and Appropriations Committee, May 2016.

[17] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State “Income Migration” Claims Are Deeply Flawed, October 2014.