To download a PDF of this report, click here.

New Jersey would have a stronger economy and healthier people if every working man and woman could take days off when they are sick without forfeiting their pay or, sometimes, their jobs. Today, though, over 1 million New Jerseyans – most of whom work in low-wage jobs – don’t get paid when they have to take off for being sick.[1]

But earned sick days don’t only benefit working people; they help employers too. By investing in their workers, business owners reap the benefits of a more productive workforce and with lower employee turnover that is both expensive and disruptive.

For most New Jerseyans, this isn’t even an issue. About 3 million workers – 7 out of every 10 – have the right to take time off with pay if they are sick. Typically, workers earn an hour of sick time for every 30 hours they work, but many businesses simply provide sick time to their workers without demanding that they earn it by counting work hours. Seventy percent of New Jersey businesses grant the right of sick time already.[2] According to a 2013 poll, 83 percent of New Jersey residents support this common-sense policy.[3]

Claims by the opponents of pending legislation that giving workers earned sick days would hurt the economy don’t hold up. The experiences in numerous cities, states and countries have been just the opposite. Of the 22 most developed nations in the world, only the United States doesn’t require that all working people are entitled to earned sick days. Several cities and states across the country require earned sick days, without any harm to their economies. Often, business owners have come to favor mandatory sick days once they are implemented, as they find the policy helps their workers stay healthy and be more productive. In cities with the longest experience like San Francisco and Seattle, and elsewhere, their economies have improved after earned sick days were mandated, showing that the policy doesn’t hurt jobs and businesses.

Put in perspective, the fight for earned sick days is facing the same knee-jerk resistance that confronted advances in workers’ rights throughout American history. The arguments heard today against earned sick days closely resemble those used against such reforms as the eight-hour work day, the five-day work week and anti-child labor laws – that basic benefits for employees are “bad for business.” These dire warnings have never been borne out. The economy doesn’t suffer and often – particularly in the low-wage industries where most people lacking earned sick days work – employers experience significant savings from reduced turnover and increased productivity that easily outweigh the modest costs.

Bringing Earned Sick Days to All New Jersey Workers

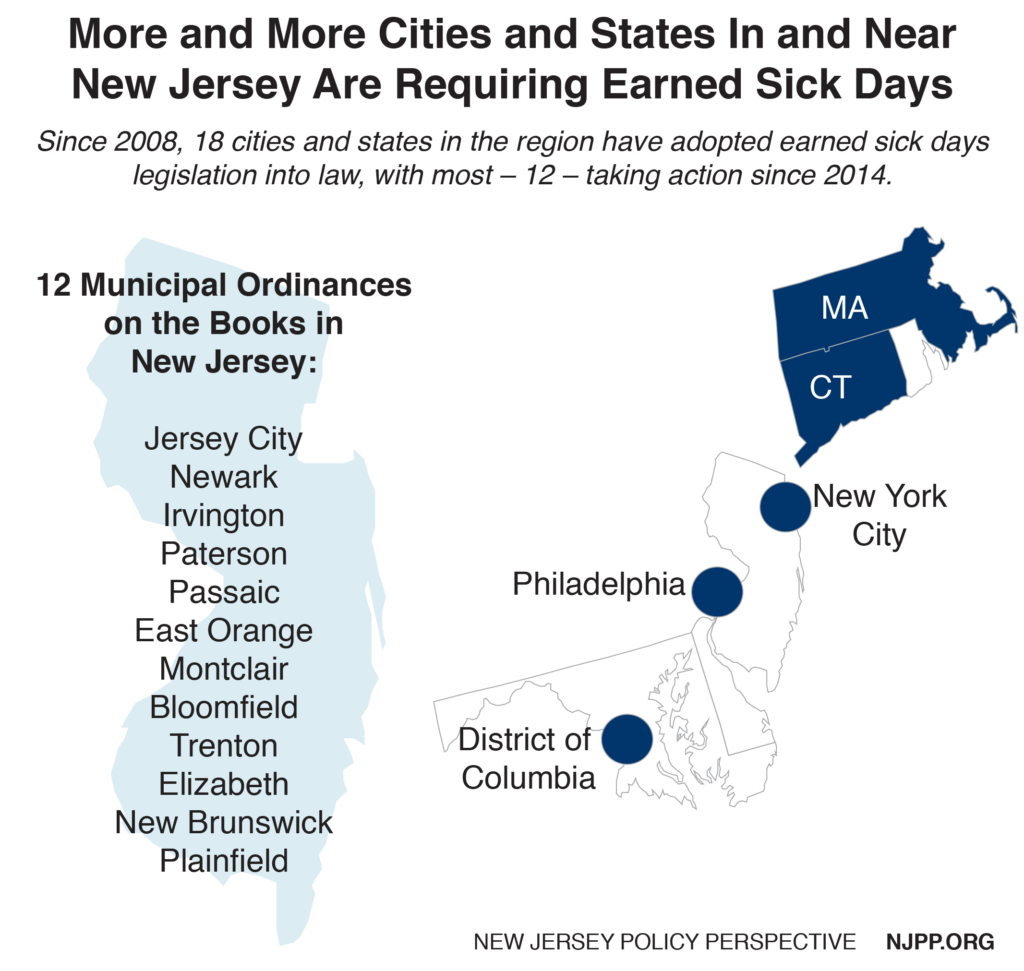

Twelve New Jersey cities have passed their own earned sick days policies: Jersey City, Newark, Irvington, Paterson, Passaic, East Orange, Montclair, Bloomfield, Trenton, Elizabeth, New Brunswick and Plainfield.

Jersey City was the first to pass such an ordinance that took effect in January of 2014. There, after a full year, many of the companies that changed their policy as a result of the new law have seen at least one, if not more than one, of several benefits (reduced turnover, improved productivity and higher-quality job applicants) – and abuse of the new policy by workers has been essentially absent. Additionally, fewer sick Jersey City employees are coming to work, reducing the risk of illness spreading around the city – an important finding that promotes both public health and a stronger economy.[4]

As more municipalities follow suit, momentum is building to pass a comprehensive state law. A bill passed by the Senate at the end of 2015 would allow all employees to accrue one hour of sick leave for every 30 hours worked. (The bill was reintroduced in the new legislative session and will need to be voted on again.)[5] Workers at businesses with up to nine employees can accrue up to 40 hours (five days) of sick leave at a time and carry it over from year to year; for workers at businesses with ten or more employees, the same rules apply, except they can accrue up to 72 hours (nine days). They could then use this paid leave to receive medical attention and recover from illness; care for an ill family member; recover, or help a family member recover, from domestic and sexual violence; or stay home when their workplace, child’s school or child care facility is closed by public officials (as would happen, for example, in a weather emergency).

All workers would start to accrue time on their first day of work and be eligible to use that time after 90 days on the job. Everyone would carry over unused sick leave from one year to the next as long as they remain below the designated limit.

Increased Productivity & Reduced Turnover Save Businesses Money

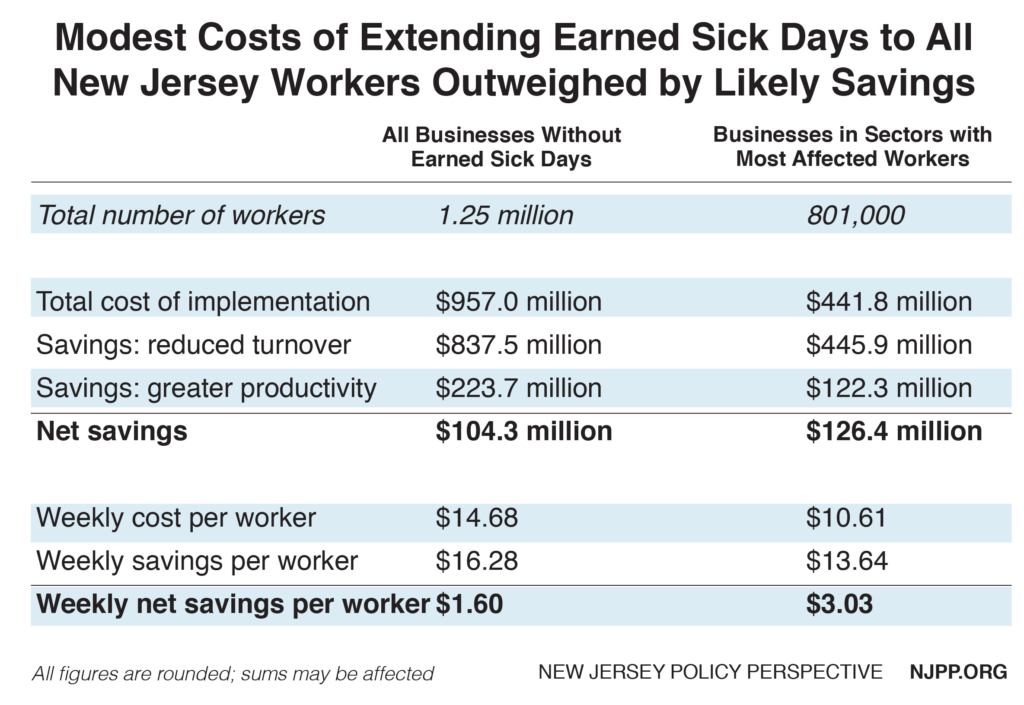

As a result of increased productivity and reduced turnover, New Jersey businesses that don’t currently offer earned sick days would experience savings and reduced costs after implementing earned sick days. The entire group of businesses employing the 1.25 million workers without earned sick days[6] would save up to $104.3 million each year, while businesses in the six sectors with the largest number of workers without sick days would save up to $126.4 million a year.

When people come to work while sick, they don’t perform at their peak. This decrease in productivity due to illness, often also called “presenteeism,” has a real and negative effect on businesses. Companies that don’t offer earned sick days lose a significant amount of money per worker per year due to this phenomenon (the amount lost depends on a number of variables including hours worked and average wage).[7] This effect snowballs as workers continue working while ill, and continue to work at less than peak productivity, rather than having the opportunity to use a sick day to get well and return to peak productivity more quickly.

In addition to reduced costs from increased productivity, businesses can save from reduced employee turnover that springs from providing earned sick days. When employers don’t have to hire and train new employees to replace those who are either fired for calling out sick or who voluntarily leave for a job that has earned sick days, they can save a significant amount of money and time. In fact, turnover costs can account for up to 20 percent of annual compensation.[8]

In New Jersey, the businesses that employ the 1.25 million workers who don’t currently have earned sick days could reduce their costs by up to an estimated $1.1 billion annually if they were mandated to provide this benefit.

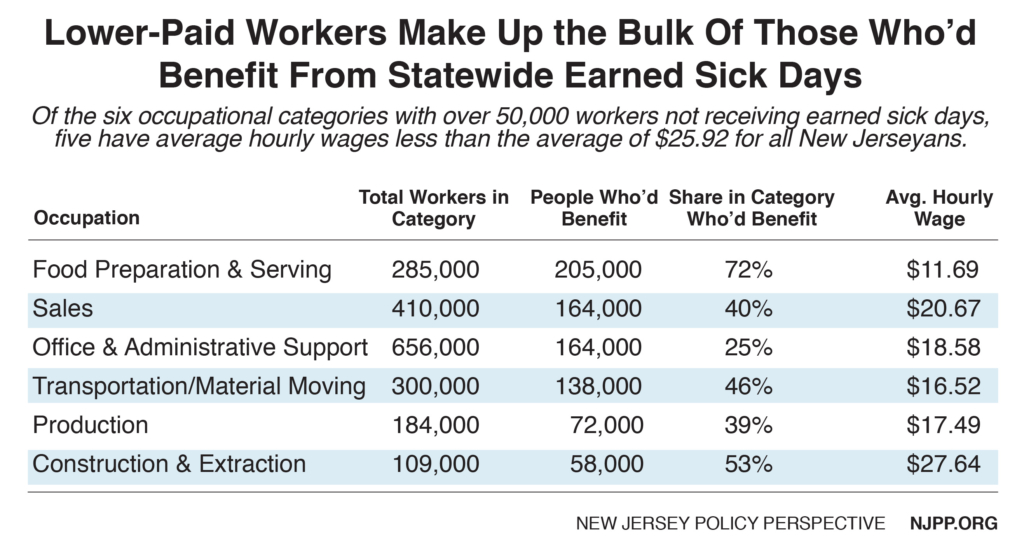

Looking only at employers in the six private-industry sectors with the most employees without earned sick days,[9] which make up 64 percent of workers who lack this benefit, the reduced costs would be up to $568.2 million a year. These sectors have large numbers of low- and middle-income workers, so earned sick days would have an outsized impact for these workers and their families.

Of course, these businesses would see a cost to implementing earned sick days, as they would with any other common-sense benefit for their workers. But in all, the savings from increased productivity and reduced turnover alone is likely to outweigh the costs. The entire group of businesses employing the 1.25 million workers without earned sick days would have a net savings of up to to $104.3 million a year, while the employers in the six specific sectors outlined above would have an annual net savings of up to $126.4 million. (The smaller group would see larger savings because it has lower costs of implementation due to lower average wages, and stands to save more money from increased productivity.)

These savings are just the immediate savings to businesses only. The state as a whole would experience additional and significant savings from reduced contagion, fewer hospital visits and lower use of emergency services (estimated at $83.17 per worker by a study that looked just at Newark[10]), plus possible boosts in job growth and economic activity as experienced by San Francisco[11] and Seattle.[12] These are important as they demonstrate the positive impact of earned sick days policies on employers, employees, and in the broader economy and population.

Benefits Go Beyond Dollars and Cents

Earned sick days do more than boost a worker’s economic security, reduce turnover and increase productivity. They greatly improve a locale’s public health, particularly during winter months and flu season. The bottom line: when sick workers stay home, the risk of contagion drops significantly.[13]

During the H1N1 flu pandemic of 2009-10, for example, employees who came to work sick across the nation caused the infection of an additional 7 million people, which led to 1,500 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[14]

Having the ability to take a day off when sick is particularly important for workers in food-related occupations. These are jobs where people who are sick while working have a higher chance of spreading disease to their fellow workers and the general public, yet in New Jersey about 72 percent of workers in food preparation and serving related occupations – approximately 205,070 people – are not granted earned sick days.[15] Nationwide, more than half of all food workers go to work sick because they have to.[16]

People who come to work sick also get injured more often, particularly in high-risk occupations like manufacturing, construction, healthcare and agriculture.[17] The American Public Health Association[18] and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration[19] advise employers to develop sick leave policies that strengthen their business by preventing sick employees from spreading disease.

Being able to take earned sick days is also very important for working parents. When they aren’t allowed to take earned sick days, parents face the difficult decision of caring for themselves and their loved ones or showing up for work – a choice which could extend the duration and increase the severity of an illness. With 80 percent of mothers primarily responsible for arranging and accompanying their children to doctor’s appointments,[20] its clear that earned sick leave is vital for working mothers.

And single parents with children may particularly benefit, as they often have fewer resources and are more likely to be sole caregivers for their children. Of the approximately 560,000 New Jersey women who lack access to earned sick days, more than one in three (about 214,000) are unmarried with children under the age of 18.[21] And about 10 percent of the New Jersey men who lack access to earned sick leave are single parents.[22]

The U.S. Lags on Paid Leave; New Jersey Can Start to Catch Up

Despite paid sick time’s obvious and widespread benefits, the United States doesn’t require employers to provide it.[23]

Legislation introduced in Congress and supported by President Obama would bring earned sick days to the 43 million Americans who aren’t now entitled to them,[24] but prospects for passage are not strong.

The federal government’s unwillingness or inability to institute such an important policy has stimulated states and cities across the country to adopt their own measures. States that have passed earned sick days legislation are Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and California; cities within California that have their own earned sick days legislation include Oakland and San Francisco. In addition to the 12 in New Jersey, other cities that require earned sick days are Washington, D.C., New York City, Philadelphia, Seattle, Portland, and Eugene.[25]

New Jersey requiring earned sick time for all working men and women would be an important step towards treating all workers with the dignity and respect they deserve. When workers and their families do better, the state and its economy do better.

Methodology

To estimate the costs and savings that would result from extending earned sick days to the occupational sectors with large numbers of low- and middle-income workers, the following assumptions were made:

- Estimated 800,751 workers in the most affected occupations (see Table 1)

- Average of 3 sick days are taken annually per worker[26]

- Average hourly wage of $17.94[27]

- Average of 7.83 hours worked per day[28]

- Presenteeism – employees working at less than peak productivity due to illness – resulting in $152.67 annually of lost productivity per worker[29]

- Turnover costs are 20% of annual compensation per worker[30]

- Turnover rate of 8.16%[31]

- Reduction in voluntary turnover up to five percentage points[32]

- Wages as 65.4% of total compensation[33]

- Payroll taxes and benefits of 34.6%[34]

In estimating the costs and savings that would result from extending earned sick days to all private sector workers in New Jersey, the following assumptions were made:

- Estimated 1,253,970 workers

- Average of 3.5 sick days are taken annually per worker[35]

- Average hourly wage of $20.93[36]

- Average of 7.74 hours worked per day[37]

- Presenteeism – employees working at less than peak productivity due to illness – resulting in $178.41 annually of lost productivity per worker[38]

- Turnover costs are 20% of annual compensation per worker[39]

- Turnover rate of 8.16%[40]

- Reduction in voluntary turnover up to five percentage points[41]

- Wages as 65.4% of total compensation[42]

- Payroll taxes and benefits of 34.6%[43]

Endnotes

[1] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Access to Paid Sick Days in the States, 2010, March 2011.

[2] New Jersey Spotlight, Judge Upholds Municipal Sick-Leave Laws, Clears Way for Proliferation, April 2015.

[3] Center for Women and Work at Rutgers University, It’s Catching: Public Opinion toward Paid Sick Days in New Jersey, October 2013.

[4] The Center for Women and Work at Rutgers University, Earned Sick Days in Jersey City: A Study of Employers and Employees at Year One, April 2015.

[5] New Jersey Legislature, Senate Bill No. 799

[6] This estimation of workers without sick days does not account for workers in cities that have recently passed earned sick days legislation.

[7] NJPP Analysis of: Goetzel, RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W; Health, Absence, Disability, and Presenteeism Cost Estimates of Certain Physical and Mental Health Conditions Affecting U.S. Employers, April 2004.

[8] Center for American Progress, There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees, November 2012.

[9] Overall, the employment sectors of Education, Training and Library Occupations and Protective Services Occupations have larger numbers of workers without earned sick days than the Construction and Extraction Occupations sector, but they also have a significant number of workers who are employed by the public sector and are thus subject to different rules and standards. For this analysis, we attempted to select the six industries with the largest number of private-sector workers who do not have earned sick days.

[10] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Valuing Good Health in Newark: The Costs and Benefits of Earned Sick Time, December 2013. Pg 4.

[11] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, San Francisco Employment Growth Remains Stronger with Paid Sick Days Law Than Surrounding Counties, September 2011.

[12] Main Street Alliance of Washington, Paid Sick Days and the Seattle Economy, September 2013.

[13] National Partnership for Women & Families, Paid Sick Days Lead to Cost Savings for All, April 2013.

[14] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Updated CDC estimates of 2009 H1N1 Influenza Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths in the United States, May 2011.

[15] NJPP Analysis of: Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2014 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates New Jersey, Occupational Employment Statistics, May 2014.

[16] Center for Research & Public Policy, The Mind of the Food Worker: Behaviors and Perceptions that Impact Safety and Operations, October 2015.

[17] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Making the Case for Paid Sick Leave, July 2012.

[18] American Public Health Association, Support for Paid Sick Leave and Family Leave Policies, November 2013.

[19] United States Department of Labor, Occupational Safety & Health Administration, Employer Guidance – Reducing All Workers’ Exposures to Seasonal Flu Virus.

[20] U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates, Table DP02 – Selected Social Characteristics in the United States, 2014.

[21] NJPP Analysis of: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates, Table S2401, 2014.

[22] NJPP Analysis of: U.S. Census Bureau, 2013 American Community Survey, 1-Year Estimates, Table S2401, 2014.

[23] Center for Economic Policy and Research, Contagion Nation: A Comparison of Sick Day Policies in 22 Countries, May 2009.

[24] National Partnership for Women & Families, The Healthy Families Act, February 2015.

[25] National Partnership for Women & Families, Support Paid Sick Days,

[26] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Paid Sick Leave: Prevalence, Provision, and Usage among Full-Time Workers in Private Industry, February 2012.

[27] Ibid 15

[28] NJPP Analysis of: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, February 2015.

[29] Ibid 7

[30] Ibid 8

[31] NJPP Analysis of: U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies, New Jersey’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators, 2013.

[32] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Valuing Good Health: An Estimate of Costs and Savings for the Healthy Families Act, April 2005. Average of range presented on Pg 9, Table 6, Cost of turnover.

[33] U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employer Costs for Employee Compensation for the Regions – June 2015, September 2015. Data on file at NJPP.

[34] Ibid 33

[35] Ibid 26

[36] Ibid 15

[37] Ibid 28

[38] Ibid 7

[39] Ibid 8

[40] Ibid 31

[41] Ibid 32

[42] Ibid 33

[43] Ibid 33