But continued progress should not be taken for granted

To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

While the President and Congressional leadership have campaigned to undermine the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the health insurance Marketplace in New Jersey has provided a national example of progress. This is on top of the state’s Medicaid expansion, which – with the eighth highest enrollment rate in the nation – has provided health coverage for a half million residents and is now the primary source of funding for opioid addiction treatment in New Jersey.

Prior to the ACA, New Jersey already had enacted strong insurance regulations and consumer protections, requiring comprehensive benefits (then called “standard plans”) and protection for individuals with pre-existing conditions, for example. While these policies were commendable, the comprehensive and high-quality coverage they mandated was by and large unaffordable.[1]

The ACA came to the rescue by providing subsidies to reduce costs, establishing the individual mandate and providing funding for outreach. All those changes made the Marketplace much more attractive to healthier individuals, which has helped keep the premium costs down for everyone. Without these components, the Marketplace’s success would be threatened.

While the state’s marketplace – a federal website (healthcare.gov) that allows consumers to shop for insurance plans in New Jersey – is not perfect, state and federal leaders need to protect and improve it – not seek to extinguish it. The overwhelming majority (78 percent) of Americans want the Trump administration to make the current health care law work better, not make it fail and (maybe) replace it later.[2]

The most immediate concern is President Trump’s threat to cut $166 million in federal subsidies to New Jersey insurers to reduce cost sharing for 145,000 low-income New Jerseyans who purchase insurance in the individual market.[3] Without these subsidies, which average about $1,200 per person, insurers would likely increase premiums by 20 or even 30 percent, making insurance unaffordable for many New Jerseyans and increasing federal costs for higher premium subsidies that are triggered by reducing cost sharing reduction subsidies.[4] This is now a full-scale emergency because insurers must decide next month what their premium rates will be and if they will even stay in the marketplace.

New Jersey should join 17 other states in a federal lawsuit to challenge the Trump administration if it terminates these subsidies, now that a federal appeals court has ruled that such a challenge can indeed move forward. All of New Jersey’s bordering states (New York, Pennsylvania and Delaware) are part of the lawsuit, as are seven other states with Republican governors. In other words, there is no reason Gov. Christie shouldn’t join these efforts. His support might help avert a potential crisis and avoid the loss of desperately needed health care for many New Jerseyans.

In Congress, New Jersey’s bipartisan delegation that voted against hastily-drafted and ill-considered plans to repeal the ACA must continue to put partisan politics aside to do what is best for the health and well-being of New Jerseyans by supporting efforts to sustain federal funding of these subsidies and strongly opposing the President’s reckless and unsupportable strong-arm tactics to withhold them.

The Trump administration also needs to end its mixed signals about the individual mandate, which requires most Americans to purchase health insurance. The Internal Revenue Service must continue enforcing this critical mandate, which insures that healthy people – not just sick people – will buy coverage, helping to hold down the premiums for everyone.

It will also be critical that the Trump administration maintain outreach. It has already canceled a major outreach contract with an agency that had three sites that served most northern New Jersey communities. It was also reported recently that the administration has decided that it may not partner with outside groups, as the federal government has done for the last four years.

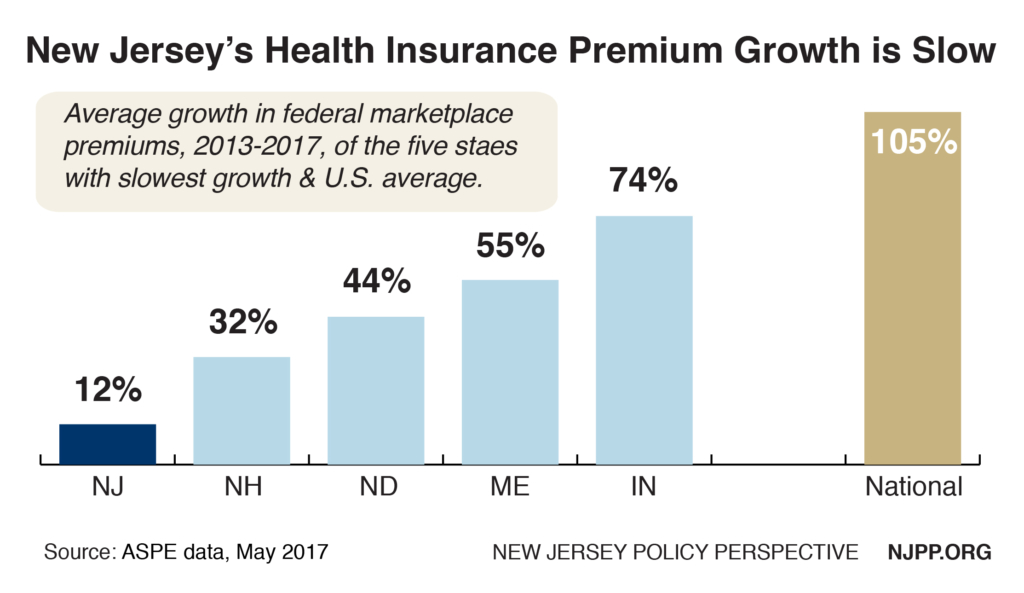

New Jersey Has Slowest Growth in Federal Marketplace Premiums

New Jersey had the nation’s slowest growth by far in federal Marketplace premiums between 2013 and 2017, according to new federal data. During this time, average premiums rose to $479 a month from $428, a 12 percent increase for an average of only 3 percent a year.[5] This is a far cry from the many double-digit annual increases before the ACA, and nearly nine times slower growth than the national average.

Adjusting for health care inflation during this time (5.6 percent annually[6]), there was a 2.6 percent annual decrease in New Jersey’s average premiums – amounting to about $144 million savings in 2017 alone in the Marketplace.[7] What’s more, 82 percent of New Jerseyans enrolled in the Marketplace received premium subsidies, which offset any premium increase for most consumers.[8] As a result of this slow growth in premiums, New Jersey fell from having the highest premiums in the nation in the federal marketplace to 21st in just four years.

Adjusting for health care inflation during this time (5.6 percent annually[6]), there was a 2.6 percent annual decrease in New Jersey’s average premiums – amounting to about $144 million savings in 2017 alone in the Marketplace.[7] What’s more, 82 percent of New Jerseyans enrolled in the Marketplace received premium subsidies, which offset any premium increase for most consumers.[8] As a result of this slow growth in premiums, New Jersey fell from having the highest premiums in the nation in the federal marketplace to 21st in just four years.

These Marketplace savings were achieved in every New Jersey congressional district. There was very little difference in average savings in districts represented by Democrats ($12.3 million) and those represented by Republicans ($11.6 million). These savings mainly benefit consumers who pay the full cost of their insurance, as well as all taxpayers, because there was less need for federally-funded premium subsidies.

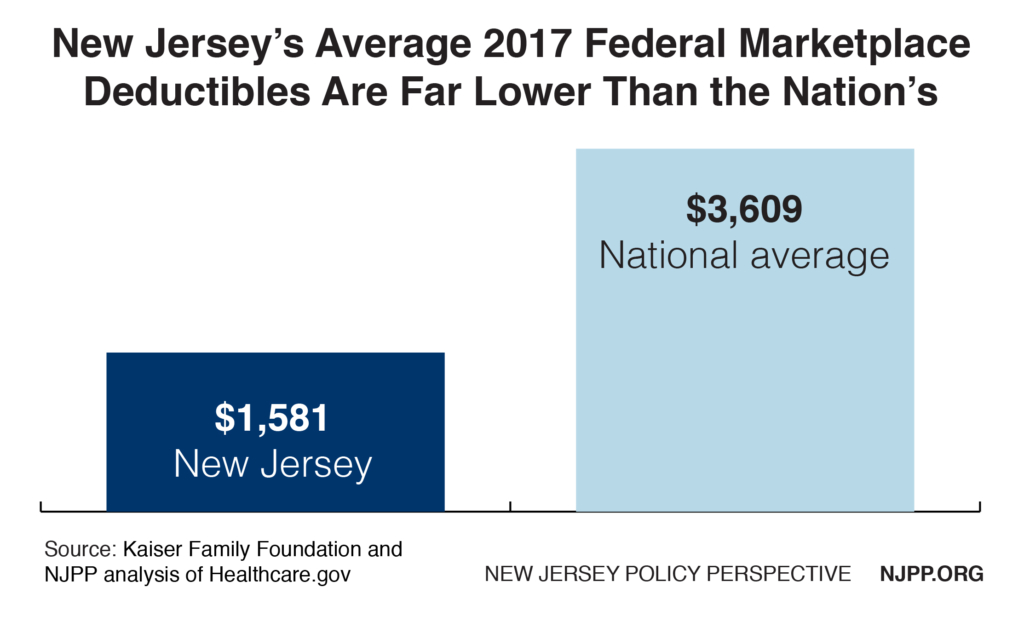

New Jersey’s Deductibles Are Far Lower Than in Other States

The ability to keep premiums down is especially impressive because, unlike most states, New Jersey also places a cap on the deductible that can be set by insurers to help reduce consumer out-of-pocket costs.[9]

On average, deductibles in the federal Marketplace in New Jersey are about $1,600, just 43 percent of the national average ($3,609).[10] (New Jersey also offers one plan that has no deductible.) While individuals in other states can face deductibles of up to $6,000, in New Jersey there is a $2,500 cap on nearly all marketplace plans. The only exceptions are “Bronze” plans, which have the highest cost sharing, but even that deductible is capped at $3,000 for a New Jersey individual. Only 12 percent of all New Jerseyans who have selected plans in the marketplace have opted for a Bronze plan, a rate that is 25 percent lower than the national average of 16 percent.

New Jersey’s Marketplace Is Stable

Opponents of the ACA contend that insurers are abandoning the Marketplace, leaving consumers with no coverage. While this is hardly true nationally – in fact, just one percent of all the nation’s counties are without at least one insurer (and most of them are sparsely populated rural areas) – it is especially not true in New Jersey, where all 21 counties have a choice of two (and next year, perhaps three) insurers.

While three out of New Jersey’s initial five Marketplace insurers did exit last year, one (Oscar) is reportedly likely to return next year. New Jersey has two insurers and 18 plans to choose from in the Marketplace this year. This includes Horizon, the largest insurer in the state and the only non-profit. Recently Standard and Poor’s maintained Horizon’s “A” credit and said its outlook was described as “stable.” In addition, New Jerseyans have a choice of five insurers outside the marketplace – an attractive option for consumers not eligible for subsidies.

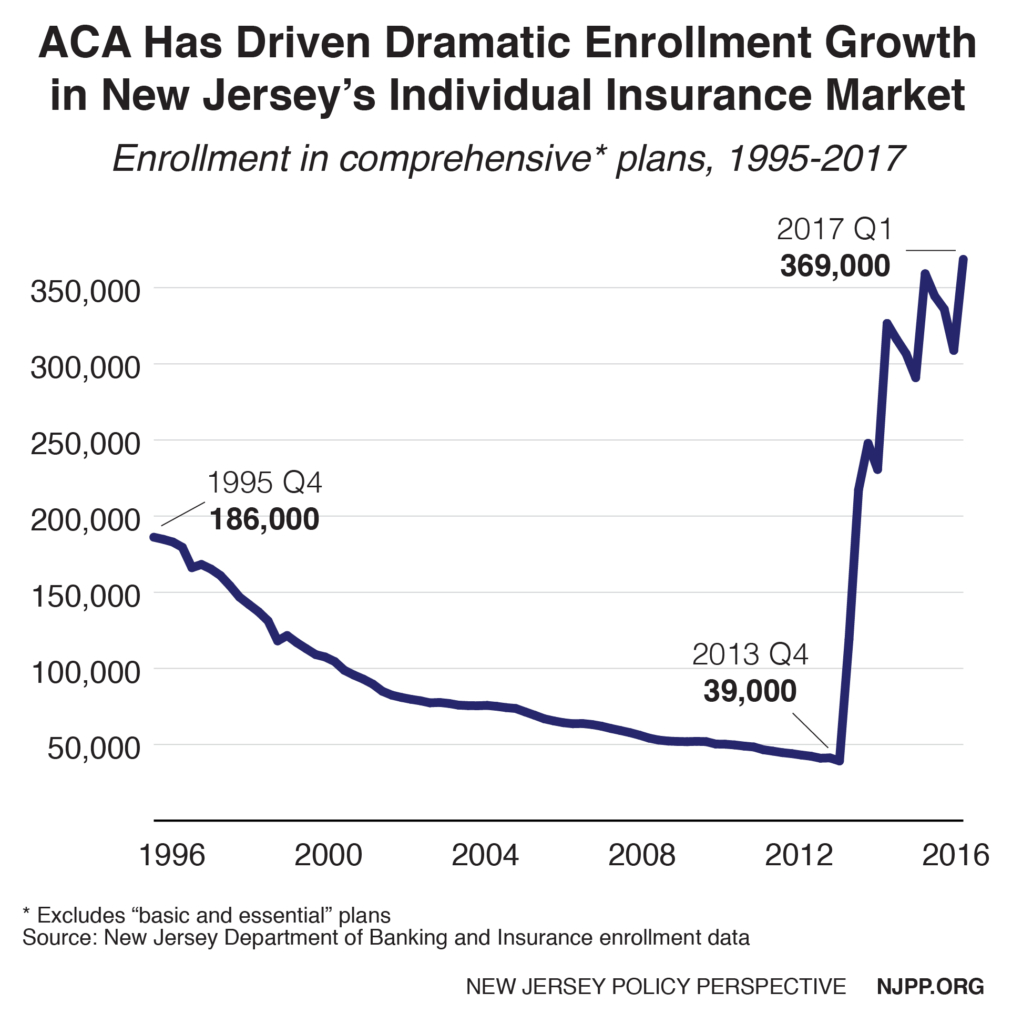

Record Number of New Jerseyans Getting Coverage in Individual Insurance Market

Meanwhile, despite the threats emanating from Washington, enrollment in New Jersey’s individual insurance market continues to grow, according to new state data. In 2017’s first quarter (which reflects the open enrollment period), enrollment grew by 19 percent to 369,000 covered individuals (this includes about 265,000 individuals in the Marketplace and 104,000 who purchase insurance outside the Marketplace).[11] This impressive growth defied the Trump administration’s elimination of all advertising and other outreach in the last week of open enrollment and Gov. Christie’s refusal to establish a state-run marketplace that would have brought more than $100 million in federal funding to New Jersey.

This progress is even more remarkable considering that before the ACA, comprehensive plans for individuals were in a death spiral. From 1995 to 2013, enrollment decreased by 78 percent, leaving only 39,000 New Jerseyans who could afford coverage. Since the Marketplace started in 2014, enrollment has increased 840 percent.

Endnotes

[1] This became such a big problem that the state went so far as to enact a statute P.L. 2001, chapter 368 establishing bare bones policies (called “Basic and Essential”) which reduced the premiums by allowing modified community rating and providing more limited coverage which proved popular with consumers when sold with riders that provided more comprehensive coverage.

[2] Kaiser Family Foundation, Poll: Large Majority of the Public, Including Half of Republicans and Trump Supporters, Say the Administration Should Try to Make the Affordable Care Act Work, August 2017. http://www.kff.org/health-reform/press-release/poll-large-majority-of-the-public-including-half-of-republicans-and-trump-supporters-say-the-administration-should-try-to-make-the-affordable-care-act-work/

[3] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Interactive Map: Cost-Sharing Subsidies at Risk Under House GOP Health Bill, March 2017. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/interactive-map-cost-sharing-subsidies-at-risk-under-house-gop-health-bill

[4] American Academy of Actuaries, Cost-Sharing Reductions: What Are They And Why Do They Need To Be Funded?, July 2017. http://www.actuary.org/content/cost-sharing-reductions-what-are-they-and-why-do-they-need-be-funded-0

[5] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of The Assistant Secretary For Planning And Evaluation, Individual Market Premium Changes, 2017, https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/individual-market-premium-changes-2013-2017

[6] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, NHE Summary including GDP, CY 1960-2015, (https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html) and National Health Expenditure Projections 2016-2025 (https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/proj2016.pdf)

[7] Savings were likely also achieved outside the marketplace but no data was available.

[8] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of The Assistant Secretary For Planning And Evaluation, Compilation of State Data on the Affordable Care Act, December 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/compilation-state-data-affordable-care-act

[9] This report did not examine co-payments and co-insurance in New Jersey compared to other states

[10] Kaiser Family Foundation, Impact of Cost Sharing Reductions on Deductibles and Out-Of-Pocket Limits, May 2017 (http://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/impact-of-cost-sharing-reductions-on-deductibles-and-out-of-pocket-limits/) and NJPP analysis of healthcare.gov for New Jersey average premium

[11] New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance, Market Summary, http://www.nj.gov/dobi/division_insurance/ihcseh/enroll/1q17ihcmarket.pdf