New Jersey is home to one of the largest immigrant populations in the nation, yet unjust immigration enforcement practices hold many people back from fully participating in and contributing to our communities. Each year, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) holds tens of thousands of immigrants in unsafe and inhumane conditions at detention facilities across the country, four of which are located in New Jersey.[1] During the past five years, over 15,000 immigrants have been ordered to be deported following court decisions in New Jersey, including 4,036 in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 alone.[2][3] Even as immigrants risk their lives as essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, ICE arrests, detention, and deportation continue to compromise public health, separate families, and destabilize communities.[4]

ICE Detention Practices Violate Human Rights and Harm Public Health

New Jersey’s immigrant detention facilities — the Elizabeth Detention Center, which is operated by the private company CoreCivic, as well as public jails in Bergen, Essex, and Hudson Counties — regularly violate the human rights of those detained and are infamous for unsanitary conditions and medical neglect.[5] Over the last year, the COVID-19 pandemic has further intensified these health and safety concerns. ICE continues to book immigrants while neglecting to follow health and safety guidelines, causing outbreaks at all four immigrant detention facilities in New Jersey.[6] ICE has further compromised public health by continuing to transfer people between facilities, including New Jersey jails with confirmed cases of COVID-19.[7]

Federal Immigrant Enforcement Tactics Worsen Economic Inequities

The immigration enforcement system deepens the inequities upon which it is built. When immigrants are unable to care for their families or miss work because they face detention or deportation, the harms ripple through their families and communities.[8] Over 1,000 immigrants have been deported from New Jersey in each of the last four years.[9] In addition, many immigrants are separated from their families and communities when they are detained while awaiting their case to be heard in an immigration court. New Jersey has the fifth largest backlog of cases pending before the immigration courts.[10] With 69,788 cases awaiting an immigration hearing, cases can remain pending for months or years. As of February 2021, the average length of time cases have been waiting for an immigration court decision in New Jersey is 1,053 days —nearly three years.[11]

While some detained immigrants have the opportunity to be released before their trial on a cash bond, bonds are often prohibitively expensive. Among the 1,198 cash bonds granted in New Jersey last year, the median bond amount was $12,000.[12] This is out of reach for many immigrants, as more than 1 in 3 (37 percent) non-citizens in New Jersey live at less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level.[13] A $12,000 cash bond equates to roughly one-third of the median earnings for non-citizens (median earnings among non-citizens for full-time, year-round workers is $32,075 for women and $42,905 for men).[14] The use of cash bonds as a pathway to release, thus, disproportionately harms immigrants with the least resources.

State and Local Law Enforcement Collaboration with ICE Intensifies Racial Injustice

The criminal justice and immigration systems in the United States are deeply entangled — and both are rife with racial inequities.[15] The rate of incarceration among Black people in New Jersey is 12 times that of white people, which is among the largest disparities in the country.[16] Because ICE relies heavily on state and local law enforcement to identify and arrest non-citizens, the immigration system further entrenches the racial disparities in the criminal legal system.[17] As a result, Black immigrants are disproportionately represented among detained immigrants facing deportation on criminal grounds.[18]

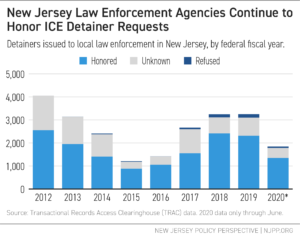

One way that individuals are channeled from the criminal legal system to the immigration enforcement system is through ICE detainer requests. When federal immigration authorities want to take custody of someone who has been arrested by another law enforcement agency, they can file a written notice (Form I-247) to local, state, or federal law enforcement to request that the agency detain an individual for an additional 48 business hours after their scheduled release.[19] Since 2010, ICE has issued over 32,000 detainer requests to law enforcement agencies in New Jersey.[20]

Immigration detainer requests are non-binding: law enforcement agencies have discretion over whether or not to honor them.[21] Yet, law enforcement agencies in New Jersey generally comply with these requests and have only refused a very small portion, 6 percent or less each year, according to ICE’s records collected by Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) through Freedom of Information Act requests.[22] Consistent with ICE’s well-documented lack of transparency, TRAC notes that law enforcement agencies’ refusal to honor detainer requests is an optional field in ICE’s database and may not be reliably recorded.[23]

Strengthening Fair and Welcoming Policies Can Improve Public Health and Safety

Fair and welcoming policies are an important tool for limiting the harm caused by uneven and inhumane immigration enforcement practices.[24] In 2018, New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal took an important step toward limiting cooperation with federal immigration authorities by issuing the Immigrant Trust Directive.[25] While this Directive places certain limitations on the voluntary assistance that state and local law enforcement officers in New Jersey can provide to federal immigration authorities, the policy is both temporary and limited in scope. The Directive, for example, allows for state and local law enforcement cooperation with ICE in situations involving certain criminal offenses. The 2019 annual reporting data on the Directive showed that the vast majority of cooperation with federal immigration authorities was conducted by state and county corrections agencies. Between the implementation of the Directive and the end of year (March 15 to December 31, 2019), correctional facilities reported that they continued to detain an individual beyond the time they would otherwise be eligible for release for ICE 403 times, provided ICE with access to a detained person 551 times, and provided notice of a detained individual’s upcoming release 779 times.[26]

Just as the inequities in the immigration enforcement system were created through policy decisions over several decades, they can too be improved through policy changes. By building upon the Immigrant Trust Directive with stronger fair and welcoming policies, lawmakers can reduce cooperation between local law enforcement and federal immigration enforcement. In addition, by protecting residents’ personal information and limiting immigration enforcement in public facilities, New Jersey can improve residents’ access to critical resources and public services, like schools and hospitals. Lawmakers can further limit the state’s participation in human rights abuses by prohibiting public and private entities from entering into, renewing, or extending immigration detention contracts. Taken together, these policies will better honor the dignity and respect of New Jersey’s diverse communities and help create a truly fair and welcoming state for all.

End Notes

[1] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detention.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/detention/

[2] Federal Fiscal Years (October to September) 2016 to 2020.

[3] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Outcomes of Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court by Nationality, State, Court, Hearing Location, and Type of Charge.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/court_backlog/deport_outcome_charge.php

[4] Kerwin, Donald; Mike Nicholson, Daniela Alulema, and Robert Warren. (2020) “US Foreign-Born Essential Workers by Status and State, and the Global Pandemic.” https://cmsny.org/publications/us-essential-workers/

[5] Alvarado, Monsy. (2020) “NJ immigrant detention center may close as landlord moves to end deal with ICE contractor.” NJ Spotlight. https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/2020/07/15/nj-detention-center-may-close-owner-moves-end-ice-contract/5439615002/; Human Rights First. (2018) “Ailing Justice: New Jersey.” Human Rights First. https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/Ailing-Justice-NJ.pdf

[6]Vera Institute. 2020. “Tracking COVID-19 in Immigration Detention.” https://www.vera.org/tracking-covid-19-in-immigration-detention

[7] Evans, Noelle. March 22, 2020. “Advocates call for ICE detainees’ release at Batavia amid threat of possible COVID-19 outbreak.” WXXI News. https://www.wxxinews.org/post/advocates-call-ice-detainees-release-batavia-amid-threat-possible-covid-19-outbreak; Mikati, Massarah. December 2020. “Transfers from Batavia ICE to Rensselaer County Jail raise concerns about COVID-19.” Times Union. https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Transfers-from-Batavia-ICE-to-Rensselaer-County-15803619.php

[8] Alissa R. Ackerman & Rich Furman (2013) The criminalization of immigration and the privatization of the immigration detention: implications for justice, Contemporary Justice Review, 16:2, 251-263, DOI: 10.1080/10282580.2013.798506

[9] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Latest Data: Immigration and Customs Removals.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/remove/

[10] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Immigration Court Backlog Tool.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/court_backlog/

[11] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Immigration Court Backlog Tool.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/court_backlog/

[12] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. Immigration Court Bond Hearings and Related Case Decisions. https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/bond/

[13] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. “Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations.” https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=foreign&g=0400000US34,34.050000&tid=ACSST5Y2019.S0501&hidePreview=true

[14] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates: Table S0501. “Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations.”

[15] Migration Policy Institute. Revving Up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement under Trump and the Pushback. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/revving-deportation-machinery-under-trump-and-pushback

[16] Nellis, Ashley. (2016) “The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons.” https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

[17] Das, Alina. “Inclusive Immigrant Justice: Racial Animus and the Origins of Crime-Based Deportation. https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/52/1/Symposium/52-1_Das.pdf

[18] Black Alliance for Justice Immigration and New York University. “The State of Black Immigrants” http://www.stateofblackimmigrants.com/assets/sobi-fullreport-jan22.pdf

[19] United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “ICE Detainers: Frequently Asked Questions” https://www.ice.gov/identify-and-arrest/detainers/ice-detainers-frequently-asked-questions

[20] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detainers.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/detain/ ICE data obtained through FOIA requests submitted by TRAC. TRAC notes that law enforcement agency refusal is an optional field in ICE’s database and may not be reliably recorded. ICE does not publish systematic data on refusal rates.

[21] American Civil Liberties Union. “Ice Detainers are Non-mandatory, Optional Requests.” https://www.aclu-ia.org/en/ice-detainers-are-non-mandatory-optional-requests

[22] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “Detainers Refused.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/detain/. ICE data obtained through FOIA requests submitted by TRAC.

[23] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. “About the Data – ICE Detainers.” https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/detain/about_data.html

[24] Migration Policy Institute. (2020). “Revving Up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement under Trump and the Pushback.” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/revving-deportation-machinery-under-trump-and-pushback

[25] New Jersey Department of Law and Public Safety. “New Jersey Attorney General’s Immigrant Trust Directive.” https://www.nj.gov/oag/trust/

[26] Immigrant Trust Directive Annual Reporting Form. https://www.njoag.gov/attorney-general-grewal-releases-immigrant-trust-directive-annual-reporting-data-for-2019/