This is a version of remarks presented at the conference, State and Local Economic Development Policy: What Works for Distressed U.S. Cities?, hosted by Rutgers University-Camden and the Scholars Strategy Network on April 19, 2016. A condensed version of this blog ran as an op-ed in the April 27, 2016 edition of the Courier-Post.

In 2013, the governor and legislature cooperated to enact a law that fundamentally rewrote New Jersey’s business tax subsidy programs. Among other things, the overhaul greatly expanded the cost of these programs, loosened standards and minimum requirements for corporations receiving the tax subsidies, and removed safeguards that protected taxpayers. The legislation also heavily favored new projects in Camden, with a special formula that only Camden qualified for that took loose standards, low requirements and big-time financial rewards for corporations to a new level.

The idea was that as one the nation’s most distressed cities – and certainly the most distressed in New Jersey – that Camden needed an extraordinarily large government lever to get private investment flowing into the city.

Since then, we’ve seen more investment coming into Camden than we probably have in decades. Supporters of this strategy like to point to that as success. Case closed.

But the reality is far more complicated, and it raises a host of important economic development policy questions for all of New Jersey.

Do tax breaks really help a distressed city if they aren’t accompanied by public investment in a city’s basic physical, social and economic infrastructure? How generous is too generous, when it comes to tax breaks? What role does the state have in ensuring that these tax breaks come with enforceable corporate requirements for rebuilding a local economy and employing local residents? And, ultimately, who has more power and leverage in this equation: the state (and, by extension, the city), or corporations?

Opening the Floodgates

Since December 2013, the state of New Jersey has approved $1.1 billion in incentives to 17 companies relocating to, or pledging to stay in, Camden.

In return, these corporations are accountable for, frankly, very little. That’s the core problem with how state policymakers have addressed revitalizing Camden through tax incentives: The law governing these subsidies is overly generous to corporations, bares little teeth when it comes to helping the local economy or growing local jobs, and comes with heavy risk to all the taxpayers of New Jersey – which, of course, include the residents and business owners of Camden.

Let’s look first at jobs.

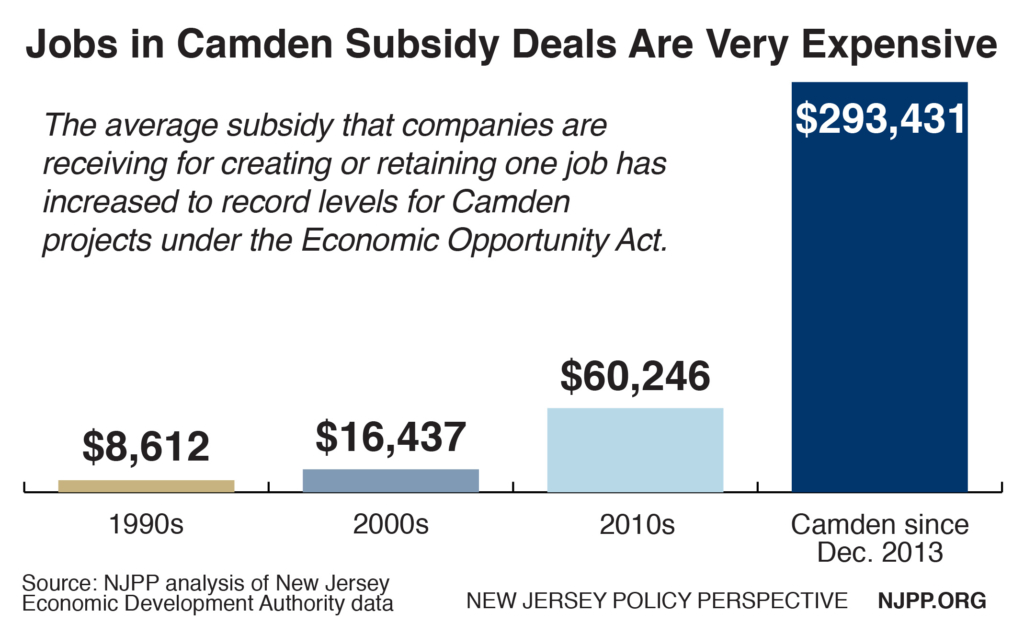

The 17 companies are required to maintain 3,897 jobs in Camden as part of their deal to receive the $1.1 billion. When measured as cost per each job, these Camden deals are literally off the charts, at an average cost of $293,000 for a single job.

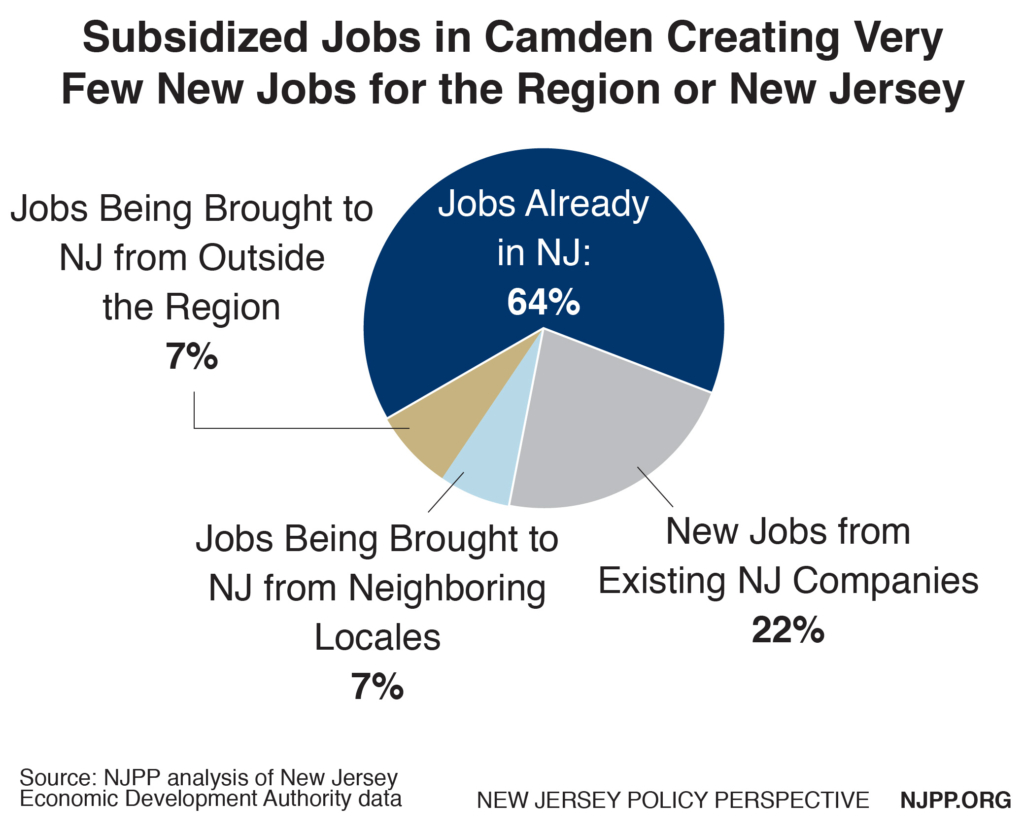

But there’s more to this story. Of those 3,897 jobs, only 36% are new to the state of New Jersey. The rest already exist elsewhere in the state, and are already filled by employees. In the case of Camden, most of these so-called “retained” jobs are not only already in the state of New Jersey – they’re already in the Camden metro area, in Cherry Hill, Moorestown and other neighboring towns.

So what’s that do for Camden’s economy? How does that help Camden’s residents who are struggling? Where’s the payoff?

Risky Business in the ‘Net Benefits Test’

Another major problem with New Jersey’s subsidy law as it plays out in Camden is a huge mismatch between the time a company is required to keep its commitment when compared with the time taxpayers must wait for the full benefits that triggered the tax break. The corporation pays lower taxes for ten years, can skedaddle after fifteen years with no penalty, while taxpayers must hold on for 35 years to realize the projected payback..

When a corporation applies for a tax subsidy from New Jersey, the state takes a variety of inputs – like the number of proposed jobs, their promised wages and other factors – and runs them through a formula designed to estimate the economic benefits to the state. This is what’s called the “net benefits test,” and it can be an important protection to taxpayers against really bad deals. But only if it’s designed properly.

In the past, in order to be approved for a tax break, most projects would need to deliver a benefit to the state of at least 110 percent – in other words, 10 percent more than the dollar value of the subsidy – over the same period that the company was committed to keeping the jobs in-state. This was usually 15 years. If the corporation didn’t meet those promised obligations, it would receive less of a tax break, or none at all.

But now, a project in Camden need only deliver a 100 percent benefit – in other words, break even – over 35 years. But the company is obligated to deliver the proposed jobs and economic activity for only 15 years at most. After that, it can move out of Camden or slash its workforce – and the state would have no recourse to claw back any of the tax credits that have already been issued.

But now, a project in Camden need only deliver a 100 percent benefit – in other words, break even – over 35 years. But the company is obligated to deliver the proposed jobs and economic activity for only 15 years at most. After that, it can move out of Camden or slash its workforce – and the state would have no recourse to claw back any of the tax credits that have already been issued.

The result is that New Jersey taxpayers are exposed to a huge amount of risk through these Camden projects. While the state touts a net economic benefit of $529 million from the Camden deals, the reality is that New Jersey is at risk of losing $273 million on them because of this one-sided arrangement.

A Case Study: Holtec International

Here is a great example of many of the shortcomings of New Jersey’s law governing these subsidies.

Holtec International was approved for a $260 million tax break to shift some existing New Jersey jobs to Camden and create some new ones at a manufacturing and engineering complex along the Delaware. In announcing the deal, Holtec said it would employ as many as 3,000 at the facility within five years of opening (just this weekend the Inquirer threw out a figure of 10,000 new jobs there). But the company’s deal with the state allows it to get its full tax break for locating a paltry 395 jobs at the facility.

As a result, the Holtec deal puts New Jersey taxpayers at great risk. If the company only met its obligations under the deal and nothing more, the state would lose $106 million – and that’s according to the state’s own estimates.

What’s more, Holtec’s CEO has pledged to hire people from Camden, as well as train local residents in the skills required to work there. This is all great – if it happens. But there are no requirements for the company to do so in order to receive the tax break.

These types of requirements – for local hiring preferences, targeted job training programs, even local beautification or community volunteering – could have, and should have, been written into the law governing these programs. If the state is going so far out on a limb here, putting up $300,000 in taxpayer funds per job, with the rationale that this level of risk is necessary to help Camden turn the corner – shouldn’t it put more community benefits into these tax subsidy deals to actually boost the local economy and help local residents?

On community benefits, number of jobs, taxpayer risk and a handful of other metrics, the state of New Jersey erred too heavily on the side of business interests in creating the framework that governs these tax breaks. As a result, there are no guarantees that this strategy will actually work to significantly boost Camden. Instead, residents of Camden will have to hitch their economic hopes on trickle-down economic development from large office buildings filled mostly with suburban commuters, and promises from big corporations like Holtec. But it didn’t have to be that way, if only policymakers would have designed the state policy in a smarter, tougher, more effective way.