To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

For over 40 years, New Jersey has used a state income tax to build strong communities and invest in working families across the state. While this has helped the Garden State become a better place to live and work, over the years powerful interests have prevented the tax code from keeping up with the times, depriving New Jersey of resources needed to build widely shared prosperity.

Today, the most well-off New Jerseyans hold a greater share of the state’s income than they have in nearly a century, thanks to decades of unequal economic growth, creating an off-balance economy in which many middle- and lower-income New Jerseyans face barriers to economic opportunity. In fact, New Jersey’s top 5 percent of households now have average incomes that are 15.6 times larger than the bottom 20 percent of households, ranking 7th in the country for income inequality.[1] Recent tax policy changes have exacerbated this trend, making it harder for New Jersey to foster the kind of investments that expand the middle class and narrow that gap.

By reforming New Jersey’s income tax code, we can help build the kind of state we want to see, where families across the income spectrum have a better chance to thrive.

Adding four brackets to the state’s income tax and increasing rates on the state’s wealthiest households would raise more than $1 billion in new revenue each year for education, aid to cities and towns and property tax relief for struggling households.

Adding four brackets to the state’s income tax and increasing rates on the state’s wealthiest households would raise more than $1 billion in new revenue each year for education, aid to cities and towns and property tax relief for struggling households.

Doing so would raise income taxes on just the top 5 percent of the state’s households, who – after federal deductions – would collectively pay $674 million a year more in income tax.[2]

This would create new brackets at $250,000, $750,000, $1 million and $2.5 million, and very slightly increase the tax rate at the existing $500,000 bracket. The tax increase would be paid almost exclusively by New Jersey’s ultra-wealthy, with the top 1 percent – households with average annual incomes of $3 million – paying 85 percent.

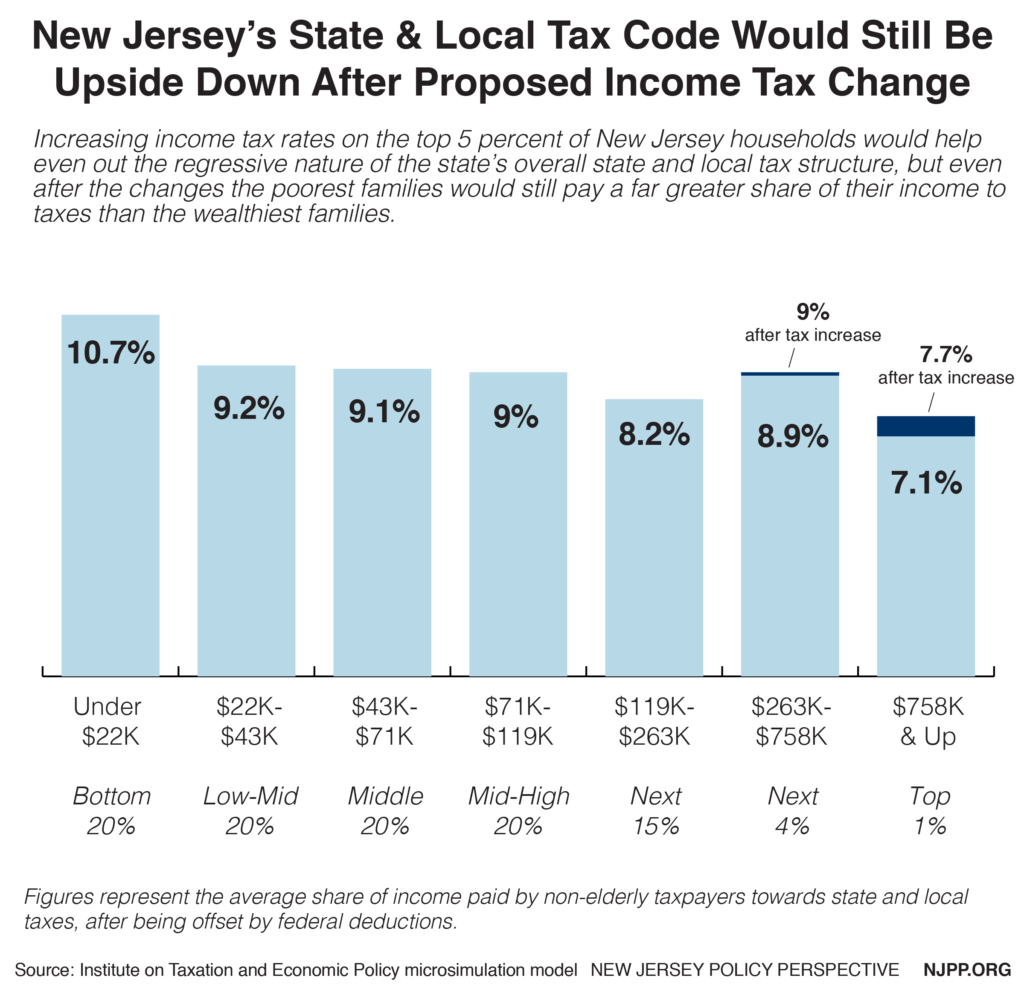

These reforms would also make New Jersey’s tax system more equitable, but it would not undo the tax code’s upside-down nature, in which low-income and middle-class New Jerseyans pay greater shares of their incomes to state and local taxes than wealthy residents. With these changes, this inequity would be slightly evened out. The share paid by the top 1 percent would rise to 7.7 percent from 7.1 percent, but that would still be lower than any other group of New Jersey families.[3]

New Jersey’s Income Tax: A History

In 1976, New Jersey took a major step toward equal opportunity by creating a state income tax and directing the new resources toward schools, cities and towns and direct property tax relief. It was meant to be a temporary fix, but the state quickly saw the benefits of making it a permanent part of New Jersey’s tax code. What started out as a relatively flat – and therefore regressive – tax of just 2 percent on income up to $20,000 and 2.5 percent on income over $20,000 has evolved over time to a robust, progressive tax with multiple brackets and fluctuating rates.

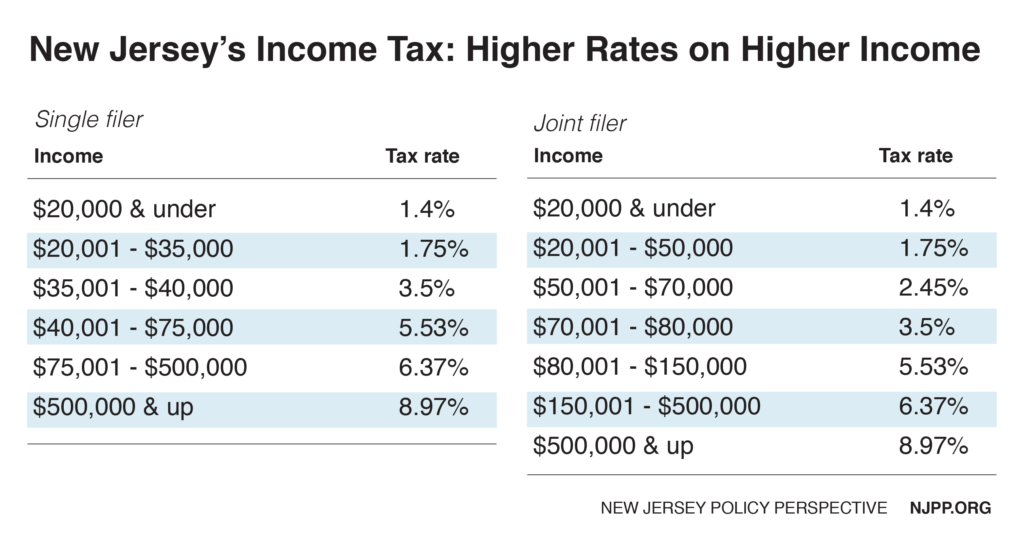

New Jersey employs marginal tax rates, which apply different tax rates to different levels of income. As income rises, it is taxed at incrementally higher rates as opposed to a flat rate which taxes at the same rate across all income levels. In other words, a New Jerseyan with $505,000 in earnings pays the top rate of 8.97 percent on only $5,000 of her earnings, not on the entire $505,000.

There are five key historical markers in the evolution of New Jersey’s income tax:

- In 1991, the top rate was doubled to 7 percent on income over $150,000 from 3.5 percent on income over $50,000, making the tax fairer and based more on the ability to pay while raising substantial new resources.

- Just a few years later, in 1994, the top rate was – like all rates – slashed by 10 percent, to 6.37 percent on income over $150,000.

- In 2004, a new top rate of 8.97 percent on income over $500,000 was introduced, marking the first significant foray into taxing those at the very top of the income scale most heavily.

- In 2009, a temporary surcharge increased the top rate to 8.97 percent on income above $400,000, 10.25 percent above $500,000 and 10.75 percent above $1 million, raising about $560 million at a time when New Jersey was experiencing an enormous budget shortfall due to the Great Recession.

- The legislature allowed the surcharge to sunset the following year and subsequent efforts to reinstate it or to increase the progressivity of the tax have been vetoed, allowing New Jersey millionaires to enjoy over $4.2 billion in cumulative tax breaks since 2010.

Today, for single tax filers, New Jersey’s income tax ranges from 1.4 percent on income up to $20,000 to 8.97 percent on income over $500,000. For couples filing jointly, the tax is slightly more graduated, with lower rates in the mid-range brackets.

All revenue raised from New Jersey’s income tax is constitutionally dedicated to fund property tax relief, which includes school aid, teacher pensions, municipal and county aid and direct relief initiatives like rebates. Despite this influx of dedicated funds, which currently tops over $14.4 billion in annual income representing 40.5 percent of total state revenue, both indirect and direct relief programs have been chronically underfunded, cut or delayed for decades. The school aid formula has been underfunded by a $1 billion almost every year since it was enacted. And the property tax relief programs for households have been an easy target for reduced payments by the Christie administration. These cuts and delays have hurt those families that depend on property tax relief the most: qualified veterans, seniors and disabled homeowners.

While the income tax is largely based on one’s ability to pay, New Jersey’s tax code as a whole is skewed toward the wealthy, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. The bottom 20 percent of New Jersey taxpayers pay an average of 10.7 percent of their income in taxes while the top 1 percent pay just 7.1 percent of their income in taxes each year.[4] And that gap is widening. Back in 2009 the bottom 20 percent was paying 10.7 percent of their income in taxes and the top 1 percent was paying 7.4 percent of their income.[5]

Lessons from Other States: Fairer Income Taxes Work

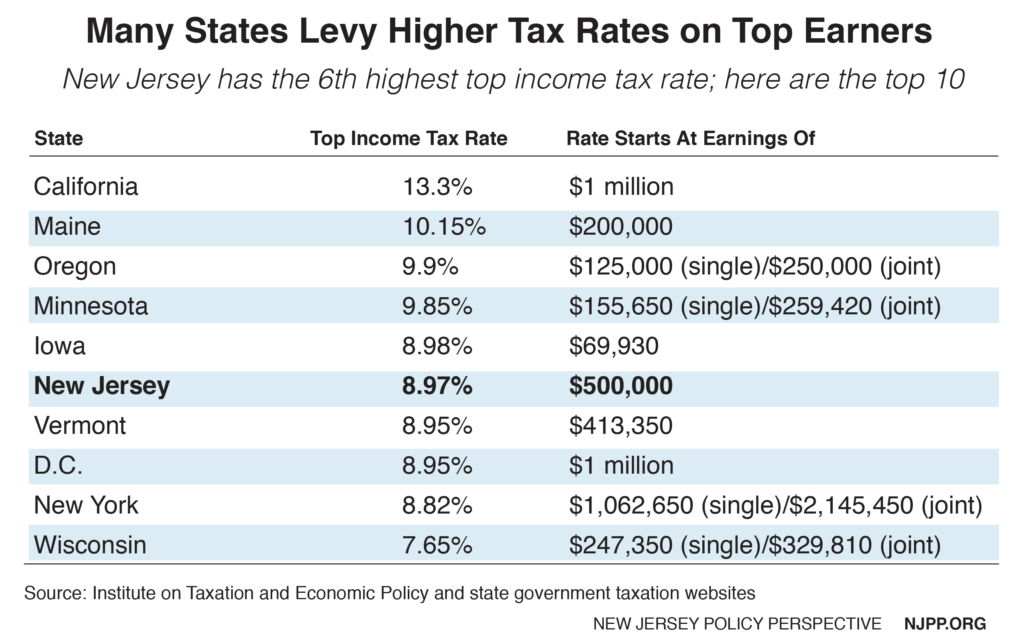

Since 2010, New Jersey’s top income tax rate has remained at 8.97 percent as repeated attempts to increase the rate were vetoed by the governor. While tax reform efforts have stagnated, though, other states have moved forward in creating more equitable income tax structures.

Today, New Jersey’s top income tax rate is no longer at the very top of the states; in fact, it is the 6th highest in the nation behind states like Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon and Maine – many of which also levy higher rates on lower incomes than New Jersey. And in three of the top ten states – Oregon, Iowa and New York – residents can end up paying higher total income tax rates, because cities and towns can levy their own income taxes in addition to state income taxes. These local income taxes are often levied precisely because they are located in places where the highest earners tend to cluster. For example, New York City’s wealthiest households pay state income tax of 8.82 percent plus an additional city income tax of 3.876 percent resulting in a total rate of 12.696 percent.

Meanwhile, New Jersey continues to rank as one of the wealthiest states in the nation – it has the third-highest ratio of millionaire households to total households,[6] the third-highest per-capita personal income[7] and the fifth highest median household income.[8]

Other states like California, for example, have changed course to rebalance their income tax code by asking top earners to pay more. In 2012, California voters decided to raise taxes on all residents, but mostly on the very wealthiest Californians, to help reinvest in public education.

Before California’s new tax plan took effect in 2013, the state’s income tax code was already quite progressive, meaning tax rates rose with income. California’s pre-2012 top income tax rate of 10.3 percent was applied to taxable income over $1 million.

The plan approved by voters expanded the 10.3 percent rate to income between $250,000 and $300,000 and created three new tax brackets: 11.3 percent for income between $300,000 and $500,000, 12.3 percent for income between $500,000 and $1 million and 13.3 percent for income over $1 million.

Those changes raised over $8 billion in additional revenue a year, which was invested in public schools and colleges and helped California erase $27 billion in debt. Meanwhile the state has enjoyed some of the strongest economic growth in the country with new jobs, credit rating upgrades and an explosion of well-off taxpayers. In fact, California’s share of very wealthy households (those with more than $1 million in income a year) has grown by 50 percent between 2011 and 2014.[9] Last year, voters decisively extended the income tax changes

California’s success has provided a roadmap for other state to follow.

Last year, voters in Maine chose to raise taxes on its higher earners by approving a new top marginal tax bracket, and for a similar initiative: to help fund K-12 education. Starting this year, income over $200,000 will be taxed at 10.15 percent – the second-highest income tax rate in the country. The new tax bracket is expected to initially generate over $150 million a year.

And Massachusetts is considering a constitutional amendment to add a second income tax bracket on the state’s highest earners. Voters will decide in 2018 whether to increase the current flat tax of 5.2 percent by four points on annual income over $1 million. Dubbed the “Fair Share Amendment,” the measure would raise between $1.6 billion and $2.2 billion each year to be spent on education, infrastructure and public transit.

Relocation Decisions by High Earners and Business Owners Are Influenced by Other Factors Besides Taxes

Claims that millionaires and small business owners spooked by higher income taxes will flee the state are commonplace, but that doesn’t make them accurate. These anecdotal stories are unsupported by real-world statistics. In fact, the majority of rigorous studies on the subject have found a negligible correlation between state taxes and interstate moves.[10]

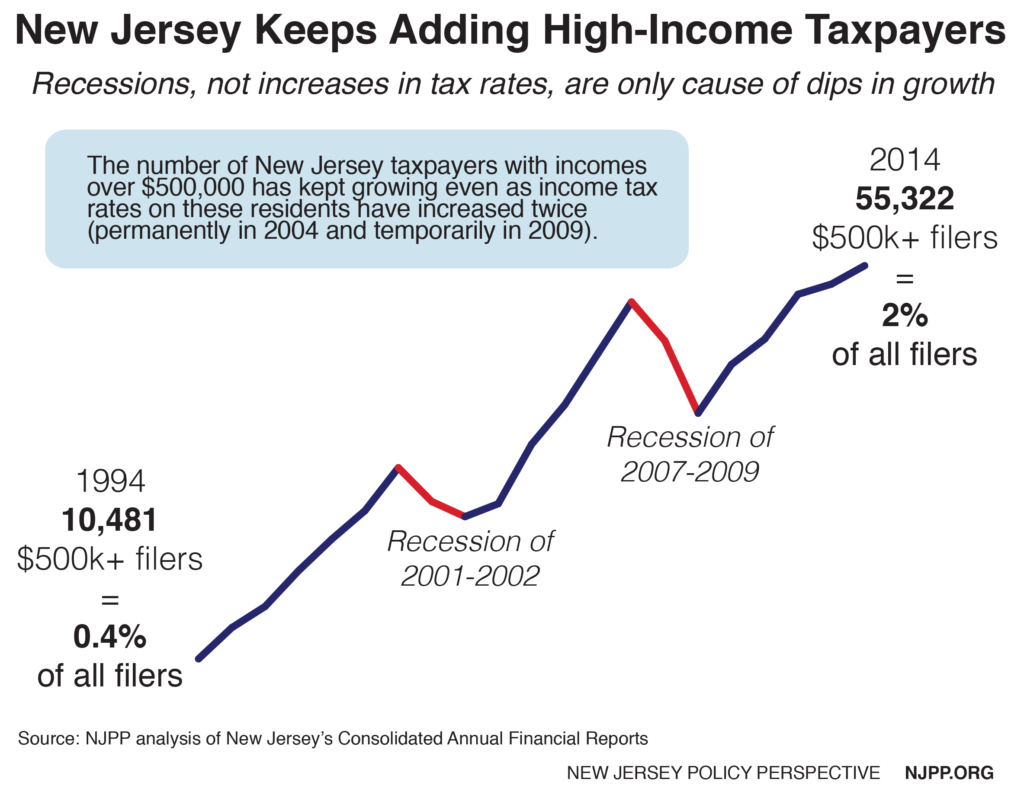

When income taxes were first raised on New Jersey’s highest earners back in 2004, one study found a slight uptick in the number of millionaires who left New Jersey. Their exit cost the state about $16 million between 2004 and 2007, but the state gained about $1 billion from those who remained.[11] In other words, the revenue loss was less than 2 percent of the revenue gained. What’s more, the number of New Jersey tax filers with income over $500,000 rose by 82 percent between 2003 and 2007, nearly doubling from 28,178 (representing 1.1 percent of all filers) to 51,187 (1.3 percent of all filers).[12]

And that trend has continued after a sharp dip during the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009. Since hitting a recessionary low point in 2009, the number of New Jersey tax filers with income over $500,000 has rebounded by 44 percent, growing from 38,496 (or 1.3 percent of all tax filers) to 55,322 in 2014 (2 percent of all filers), even as New Jersey’s overall economic recovery has remained weak.

Another way to measure wealth in New Jersey is to estimate the net worth of households.

A private wealth management firm has tracked this data for all 50 states back to 2006, and the pattern for New Jersey is consistent with the growth in high-income taxpayers.

A private wealth management firm has tracked this data for all 50 states back to 2006, and the pattern for New Jersey is consistent with the growth in high-income taxpayers.

From 2006 to 2016, the estimated number of millionaires in New Jersey – defined as those with $1 million or more in “investable assets” – has increased by more than 35,000 (or 17 percent), while the share of millionaires has risen by 14 percent. According to the latest data, New Jersey is home to 242,957 millionaires. At 7.4 percent, the state has the third largest share of millionaires in the country behind only Maryland and Connecticut.[13]

Another point of contention among business lobbyists has been the potential impact of increased tax rates on small businesses. But the fact is, most small businesses don’t make nearly enough money to fall into upper income brackets. Nationwide, only 13 percent of small businesses have $50,000 or more in taxable income in a given year. It is not too different in New Jersey.

Most Garden State businesses that file using personal income taxes (79 percent) don’t make nearly enough money to fall into upper income brackets above the $250,000 threshold.[14] Just 9 percent have taxable income over $500,000 and even fewer – 3 percent – have taxable income over $1 million.

In fact, more of these Garden State small businesses are found in the middle, and on the lower end, of the income scale than at the top, with 38 percent reporting taxable income under $75,000 and 26 percent under $50,000. These are the taxpayers and small business owners that policymakers ought to be trying to help, since they pay greater shares of their income to taxes than their wealthier peers, thanks to the state’s upside-down tax code.

Endnotes

[1] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, How State Tax Policies Can Stop Increasing Inequality and Start Reducing It, December 2016.

[2] Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy analysis of income tax proposal, 2017.

[3] Ibid 2

[4] Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States: 5th Edition, 2015.

[5] Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States: 3rd Edition, 2009.

[6] Shares of millionaire households taken from Phoenix Marketing International, Millionaires By State Ranking, 2010-2016.

[7] US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, State Personal Income 2016, March 2017.

[8] Highest median household income states taken from U.S. Census American Community Survey, 2015.

[9] State of California, Franchise Tax Board, Revenue Estimates: PIT and Corporation Tax, 2011-2014.

[10] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’ Interstate Moves, May 2014.

[11] National Tax Journal, Millionaire Migration and State Taxation of Top Incomes: Evidence from a Natural Experiment, 2011.

[12] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Consolidated Annual Financial Reports.

[13] NJPP analysis of a number of reports produced by Phoenix Marketing International.

[14] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Treasury Department, New Jersey Statistics of Income, 2014 Income Tax Returns.